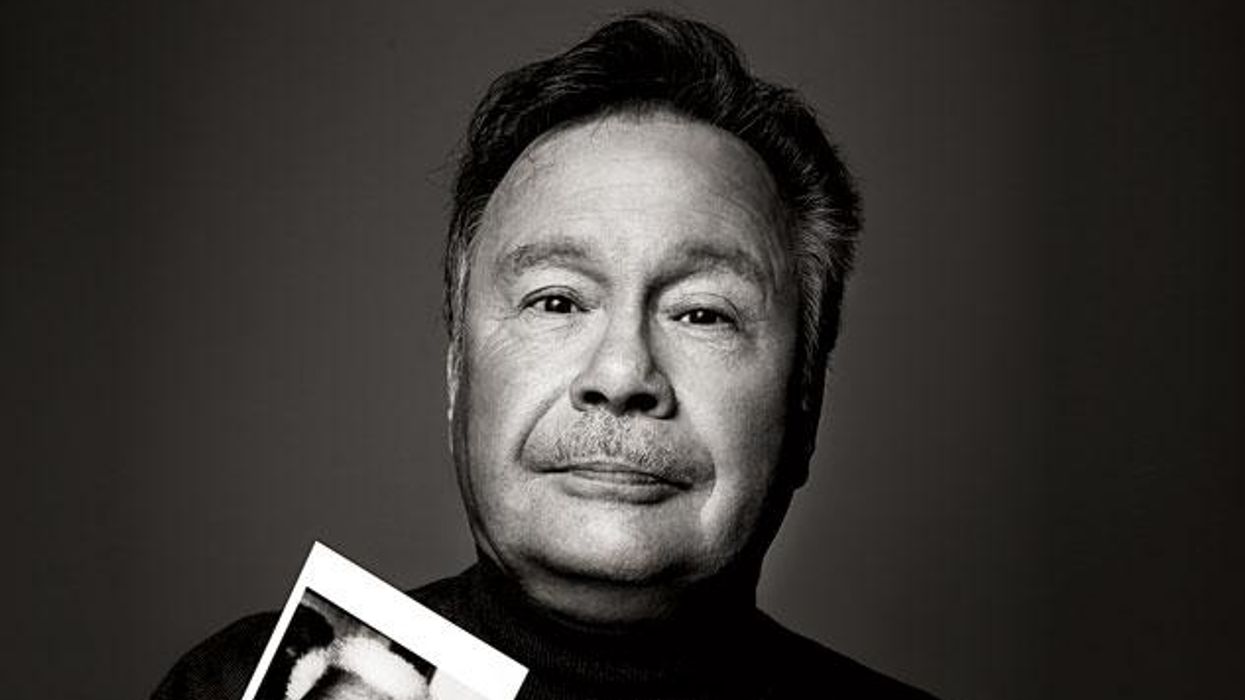

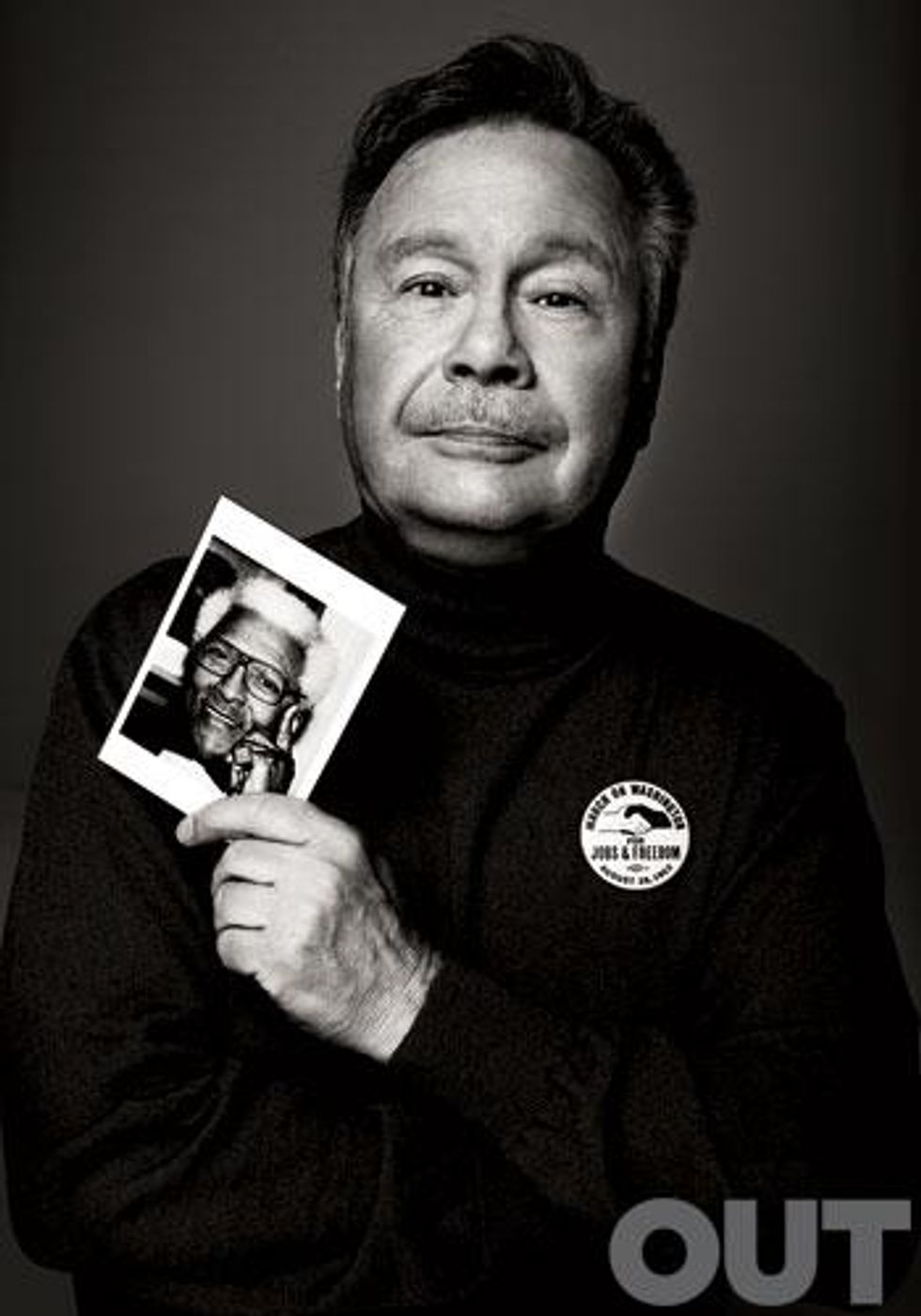

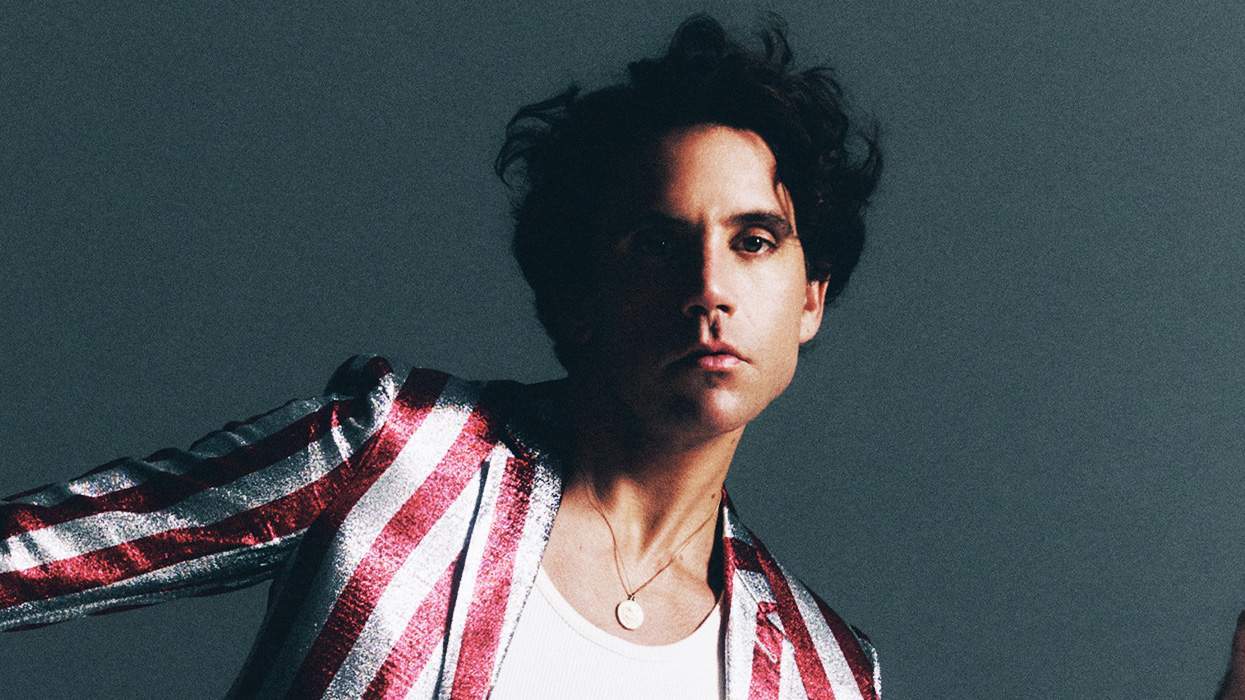

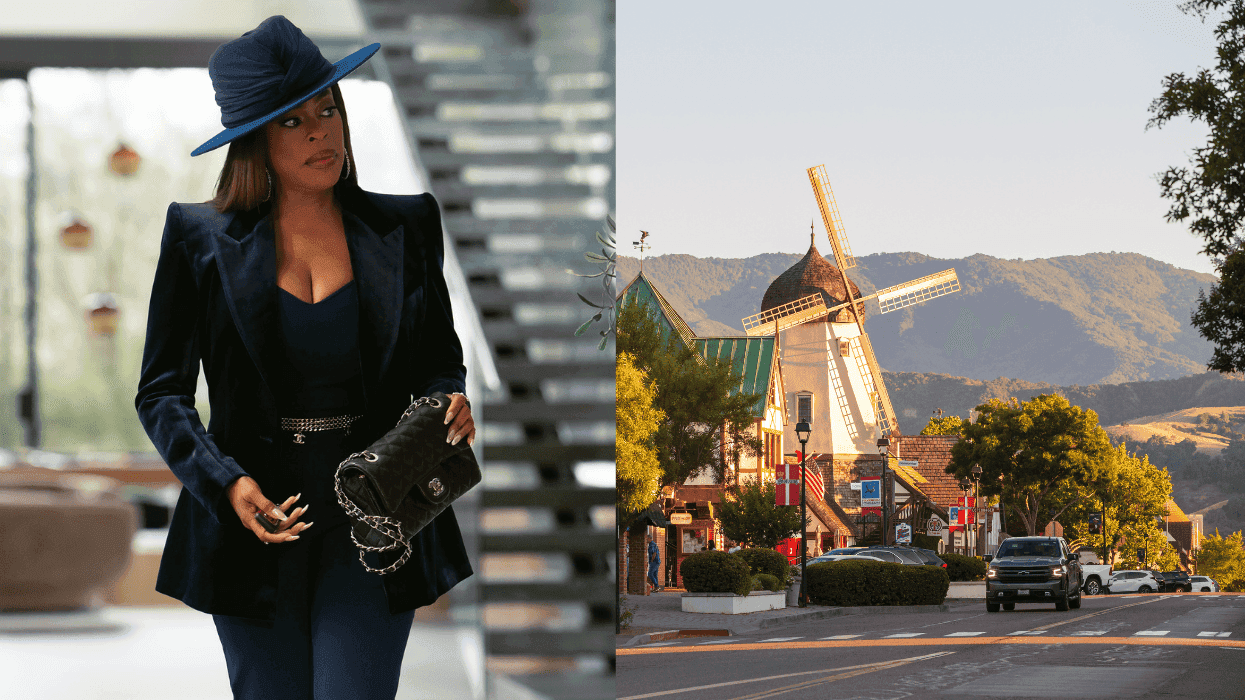

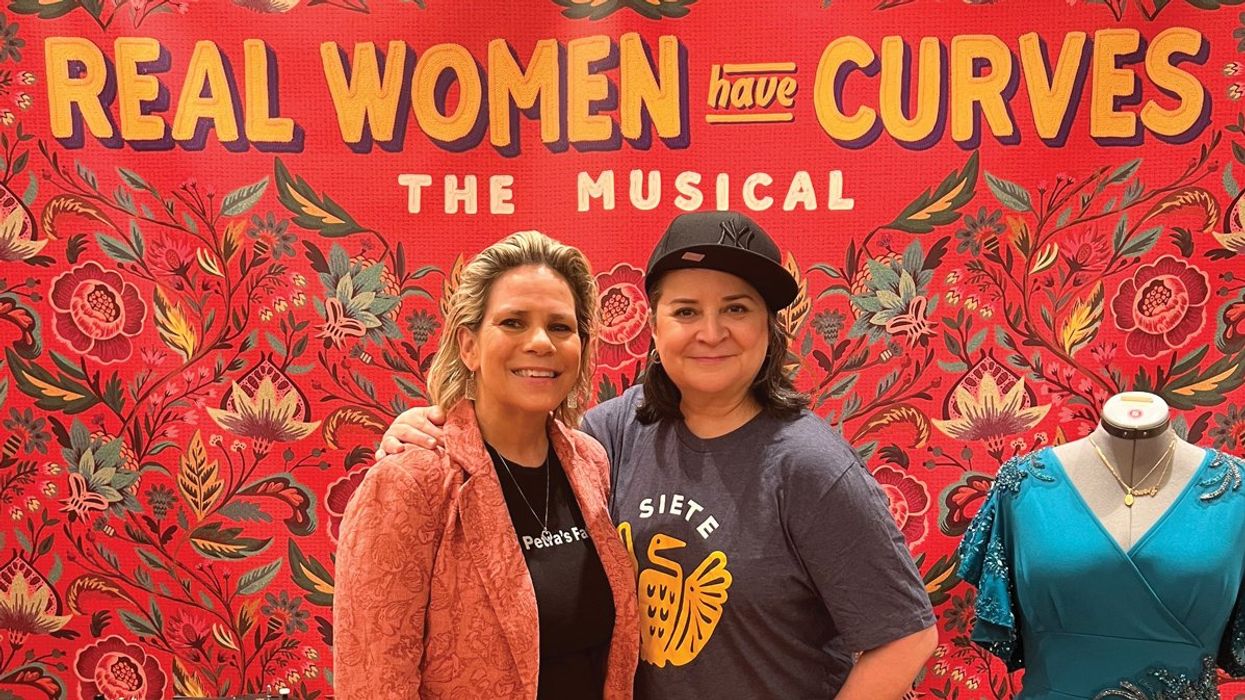

Photo of Walter Naegle (left) and Bayard Rustin | Photo courtesy of Walter Naegle

This week, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This march pressured the federal government to pass the Civil Rights Act, promoting equality in a country that had espoused freedom and equality for all since its inception, and yet had continuously come short of that mark.

Our country moves closer to its goal this year with Supreme Court rulings striking down DOMA and Prop 8. In addition, the Obama Administration has announced that it will award the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award offered by our government, to Bayard Rustin, who was a key organizer of that 1963 march. Because he was gay, Rustin was usually not accorded the recognition given to others in the Civil Rights Movement.

With the White House announcement of the recipients 2013 Presidential Medal of Freedom on August 8, 2013, more Americans are learning about Bayard Rustin, a pacifist, civil rights leader, and a top aide to Martin Luther King, Jr., who rallied over 200,000 people to march on Washington--without the aid of computers or the Internet. But there's one chapter of Rustin's life story that still remains an enigma--his personal life.

Walter Naegle, Rustin's partner for the last 10 years of his life, spoke about his relationship with Bayard and his feelings about the medal after the announcement. "I think it's wonderful. Certainly well deserved," Naegle says, sitting in the Manhattan apartment he shared with Rustin. "In Bayard's case, it recognizes him as someone who was working to expand our democratic freedoms and increase our civil liberties and our individual freedoms. There were times that he got it from both the right and the left, but this establishes him as someone who made an important contribution to the growth of the country while not pandering to either extreme."

Bayard's refusal to create a political image that would cater to a particular party often got him into trouble. "He wouldn't have been particularly comfortable being the type of political person who has to run and get votes and take positions and not veer from them," Naegle explains. "He was always very much the individual."

Rustin was never ashamed of his homosexuality, but his strong sense of self was rarely reinforced by his peers. Early in his career, he came into opposition with leaders like A.J. Muste with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), who asked Rustin to put his homosexuality aside. "The FOR was a Christian-based organization. A.J. Muste, his boss, felt that this was an illness and it needed to be treated psychiatrically," Naegle says. "He certainly thought there was a need for Bayard to be a little more discreet about his behavior."

It wasn't until Rustin's arrest in 1953 for homosexual acts that he decided to be more discrete with his liaisons for the sake of the movement. "I don't think he felt he had to suppress his sexuality," says Naegle. "He never tried to be straight or he never went around with women on his arms or anything like that. He never pretended that he was not homosexual, but I think he felt that he needed to tone down some of his urges."

According to Davis Platt, who passed away in 2008, Rustin's first major partner at the beginning of his career, Rustin never tried to hide who he was and was honest about his homosexuality if asked. "He gave off an aura of being artistic. I don't mean effeminate, but he probably looked effeminate to some people. He was tall and walked with self confidence," Platt explained. "If anybody asked him, he would have told the truth, whereas most gay people back then would deny it."

As the Civil Rights movement gained momentum during the 1950s, it was easy for Bayard to put his relationships to the side. "Davis and I are really the two people who are probably the bookends of his life," Naegle says. "I think the period between Davis and me, which was really 30 years, was packed with work. Once Montgomery started in 1955 until 1968 when Dr. King was killed, I don't think he could have done justice to a long-term relationship."

Naegle met Bayard in 1977, when his activity within the movement had quieted down. "He was still very active, but it wasn't that intense battlefront that they had during the civil rights period," Naegle says. The two met, like many New Yorkers do, while waiting for the signal to change on a busy street on a spring day. A considerable age difference--Bayard was 65 and Naegle, 27--didn't keep them apart.

"We really didn't encounter any outright prejudice. We didn't walk down the street holding hands," Nagels says. "Sometimes he would put his arm around me and we would walk down the street. I think when people saw the two of us coming, it was like, 'Well, what is this? They couldn't possible be lovers. Is it a boy taking out his elderly friend?'"

Another hurdle Rustin faced was his choices in partners. Both Platt and Naegle are white. "It was not common at all to see black and white men together," Platt explained. "I think the answer really has to be who you're attracted to. And that person might be black and that person might not be. You'll know when the time comes and you have to go with what you feel. There are people who may not be happy with my choice and if it's an issue, they will have to deal with it."

The culture of New York, where people usually leave each other alone--a live and let live philosophy of tolerance--may also have shielded Rustin and his partners from overt prejudice. But, most importantly, the Naegle family was supportive of the relationship. "We spent a lot of time with my family. My mother took vacations with us on a couple of occasions and he was known to all of my siblings," Naegle says. "There were certain members of his family that didn't want to have anything to do with us. It was really their feelings about him. They didn't like him because he was gay."

When looking back on his time with Bayard, Naegle recalls that it was their shared love for pacifism and nonviolence that allowed their relationship to thrive. "If you come from a position of being Ghandi-like, where you have self-esteem and pride in your accomplishments, but you don't think you are better than anybody else; and you are willing to say if there's a problem between the two of us, a lot of it is my problem. If both partners are doing that, then you're going to reach a point where there's some compromise or some reconciliation," Naegle says. "If you just want to get to a point where your self-esteem is intact and you feel like you've been victorious and you're the dominant partner, that's not going to be a very healthy relationship. If you want to get to the point where you can go to bed at night and sleep comfortably and feel loved, then you will be willing to compromise or see your way out of the difficulty. And I think, because both of us felt that way, we were able to do it."

Near the end of Bayard's life, he said that the next fight for civil rights would be that of lesbians and gays. It seems fitting, then, that federal government stepped forward this year via the Supreme Court to recognize gay marriage.

"He would certainly be happy, but I think he would be surprised that it's happened so quickly," said Naegle. "I think that the LGBT movement kind of took a page out of Bayard's playbook. Bayard was somebody who believed in coalition building, and especially if you're a minority group. I mean, how are you going to get a law passed if you're 10-percent of the population? You have to maximize your allies. The LGBT community has done that very successfully."

Ten years after the couple met, Bayard died in August of 1987 at the age of 75, long before the couple could legally marry. But Bayard had established a legal bond between them by adopting Naegle. Since Bayard's death, Naegle has been working with a team within the Bayard Foundation to keep his legacy alive, notably by assisting in the 2002 documentary, Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin.

"Being black, being homosexual, being a political radical, that's a combination that's pretty volatile and it comes along like Halley's Comet," Naegle says, adding, "Bayard's life was complex, but at the same time I think it makes it a lot more interesting."

Naegle attended a reception at the White House this Tuesday in commemoration of the 1963 March on Washington. The Obama Administration has also informed him that he will be the recipient of Rustin's Presidential Medal of Freedom.

For more about Bayard Rustin, visit Rustin.org