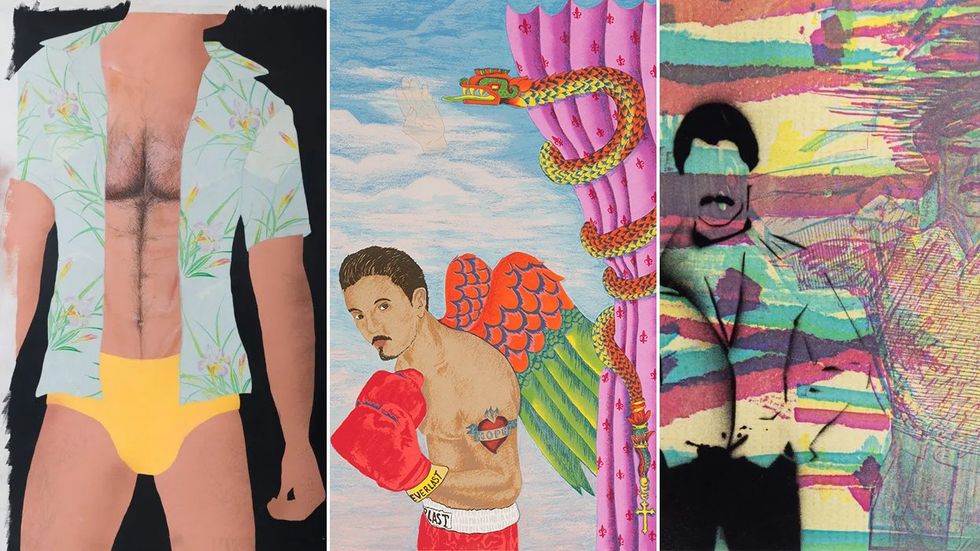

Teddy Sandoval was a pioneering, yet underrecognized, figure in Los Angeles’ Chicanx and queer art scenes. His work, which continues to resonate for its wit, irreverence, and formal innovation, is finally getting its first museum retrospective, “Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art.” As part of its U.S. tour, the exhibit is currently on view at The Contemporary Austin, where it will stay until January 2026.

A Renaissance man of sorts, Sandoval worked in an expansive array of mediums — from painting to performance art, ceramics, prints, mail art, and window displays. Active from the 1970s up until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1995, Sandoval created subversive works that queered spaces, reimagined Chicano masculinity, and forged artistic connections across local and international avant-garde networks.

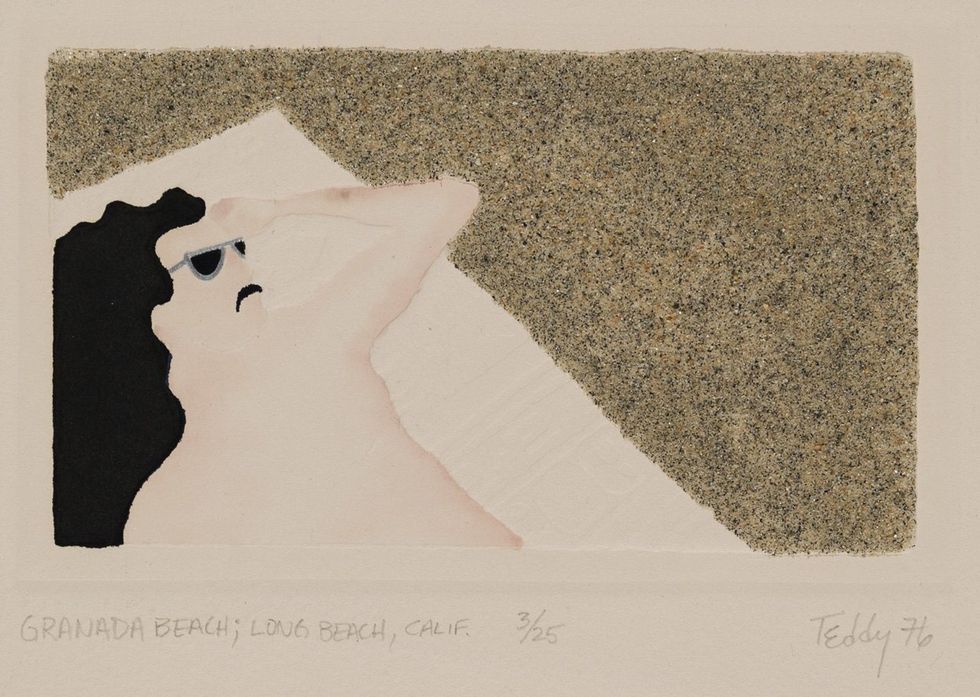

'Granada Beach' by Teddy Sandoval, 1976

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

Born in L.A. in 1949 to Mexican immigrant parents, Sandoval trained in printmaking and Chicano activism at California State University, Long Beach. His early artwork captured Long Beach’s vibrant gay scene, centered on bars, beaches, and cruising spaces. In Granada Beach (1976), Sandoval features a male sunbather, an early example of his signature use of faceless, mustached silhouettes.

Sandoval was able to turn societal changes and repression into artistic opportunities. At a time when gay bars and discos often excluded people of color and Chicanx artists were missing from view in museums and galleries, Sandoval created imaginative ways to distribute their work, including through his fictitious organization the Butch Gardens School of Art, which gives name to the exhibition.

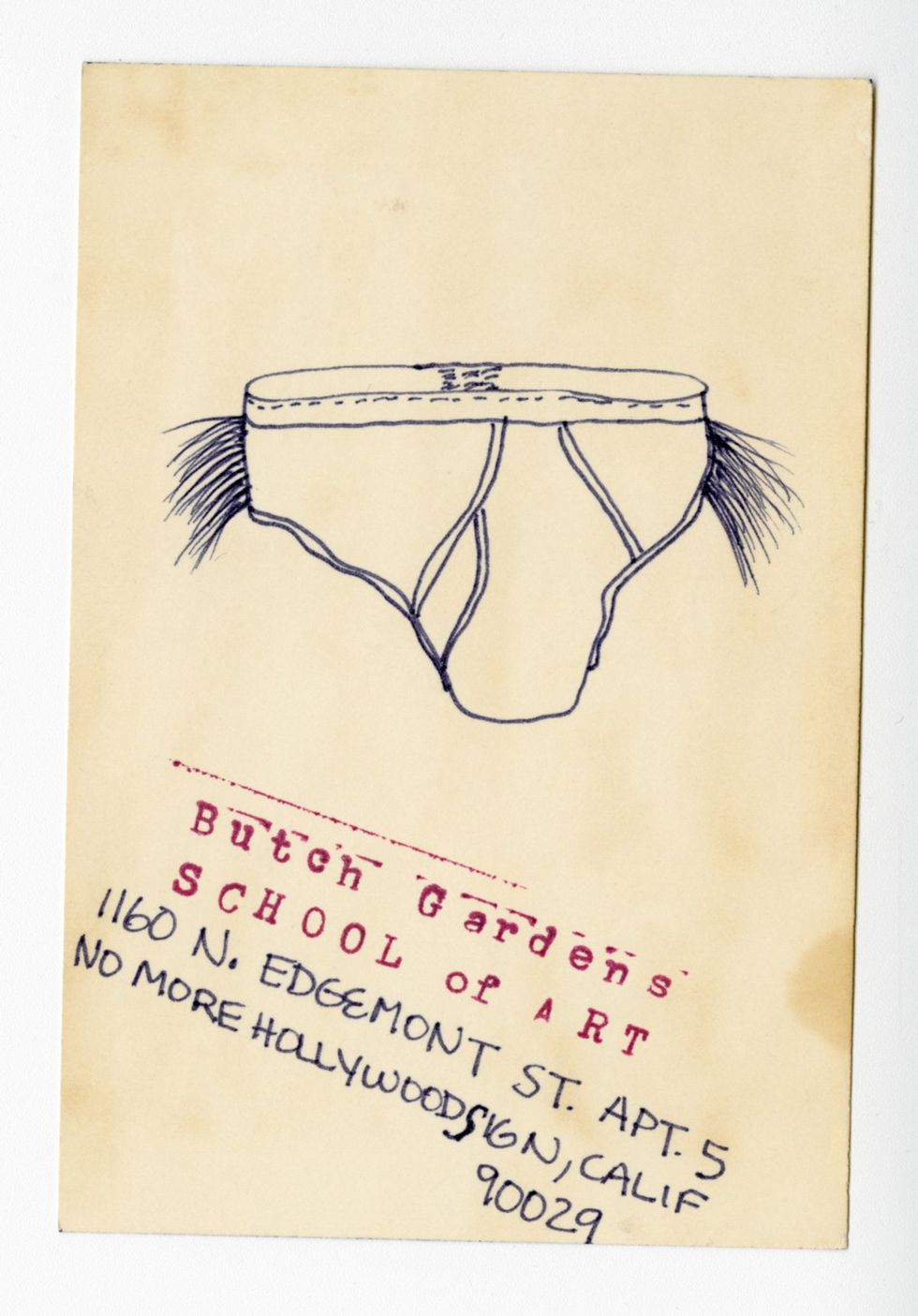

Untitled flyer for the Butch Gardens School of Art by Teddy Sandoval, circa 1970s-1980s

Teddy Sandoval estate

Between 1972 and 1975, the L.A. gay bar Butch Gardens advertised itself with a bold tagline: “Are You Butch Enough for Butch Gardens???” For many in the queer Chicanx community, the answer was a resounding yes.

Butch Gardens became a rare and vital space where Brown queers could gather without judgment. Among the bar’s regulars were Sandoval and his friends and future collaborators, including the Chicanx artists Gronk and Joey Terrill. For Sandoval, Butch Gardens was more than a watering hole, it was a source of inspiration. He borrowed the bar’s name to create the Butch Gardens School of Art, a made-up organization that blurred the line between a parody operation and actual art academy.

Untitled mail art by Teddy Sandoval, circa late 1970s-1980s

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

Then, Sandoval took his daring idea to the next level. He embraced mail art as an alternative and democratic means of circulating subversive works. Acting as if it were an official institution, Butch Gardens School of Art issued flyers and postcards and organized exhibitions that blended humor with queer eroticism. Sandoval’s mischievous drag persona, Rosa de la Montaña, often cohosted the events, while Terrill and other Chicanx artists contributed work.

Confronting a climate hostile to both their sexuality and their art, Sandoval and his peers invited recipients of the mailings to imagine themselves as students newly enrolled in this fictitious academy. In essence, they built a social network of queer connection, creativity, and resistance decades before Instagram and other social media platforms would be used to do the same.

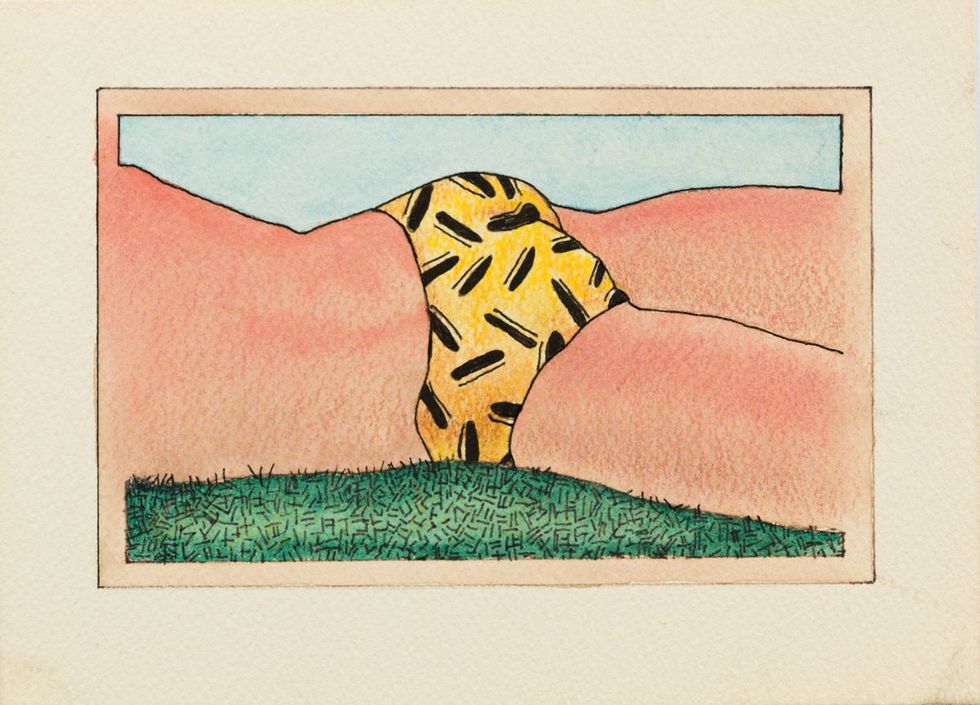

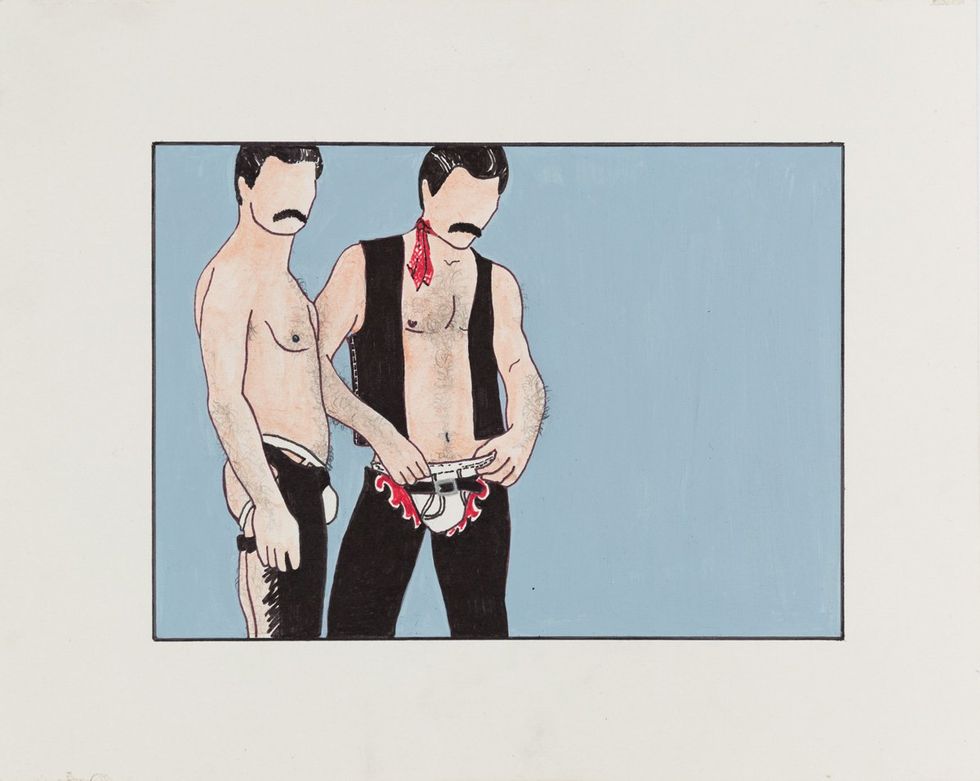

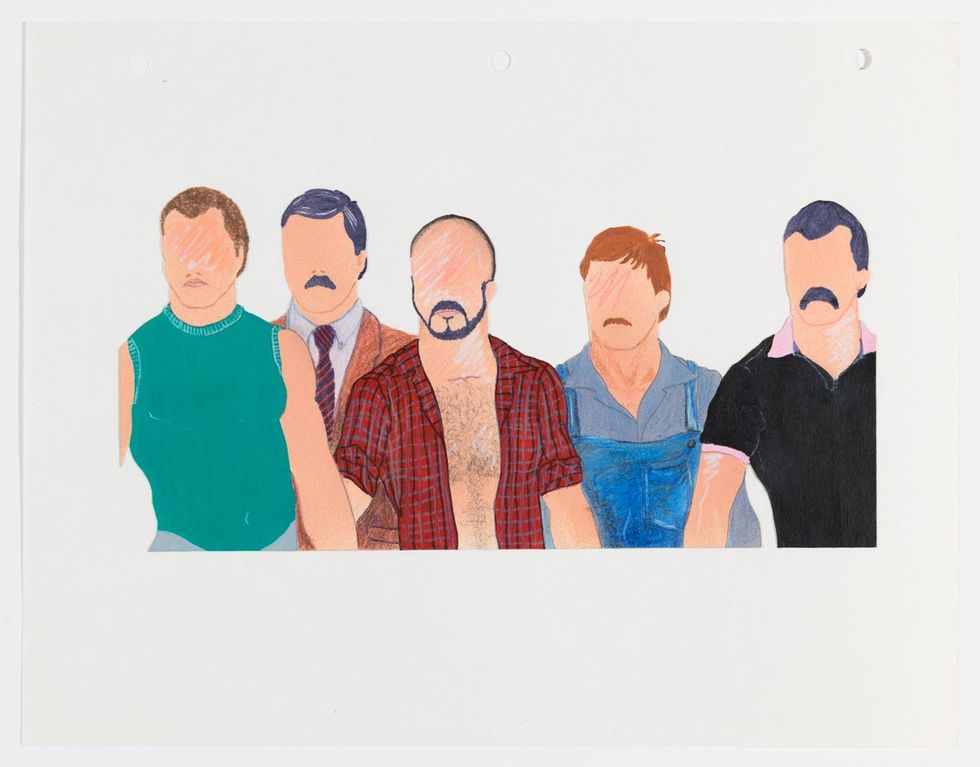

'Untitled' by Teddy Sandoval, circa late 1970s-1980s

Teddy Sandoval estate

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Sandoval developed a striking visual language: faceless male silhouettes marked only by a bold mustache. Stripped of individuality, they became the artist’s unmistakable motif — an endlessly adaptable icon that he used in every medium.

Sandoval’s artistic breakthrough occurred at a moment of seismic cultural change marked by the sexual revolution, gay liberation, and the Chicano civil rights movement. He depicted the so-called “gay clones” who flourished in San Francisco, New York, and L.A. Wearing tight Levi’s, flannel shirts, cropped hair, and full mustaches, they rejected any association of gay men with effeminacy by projecting a macho sensibility that both spoofed and embraced working-class archetypes.

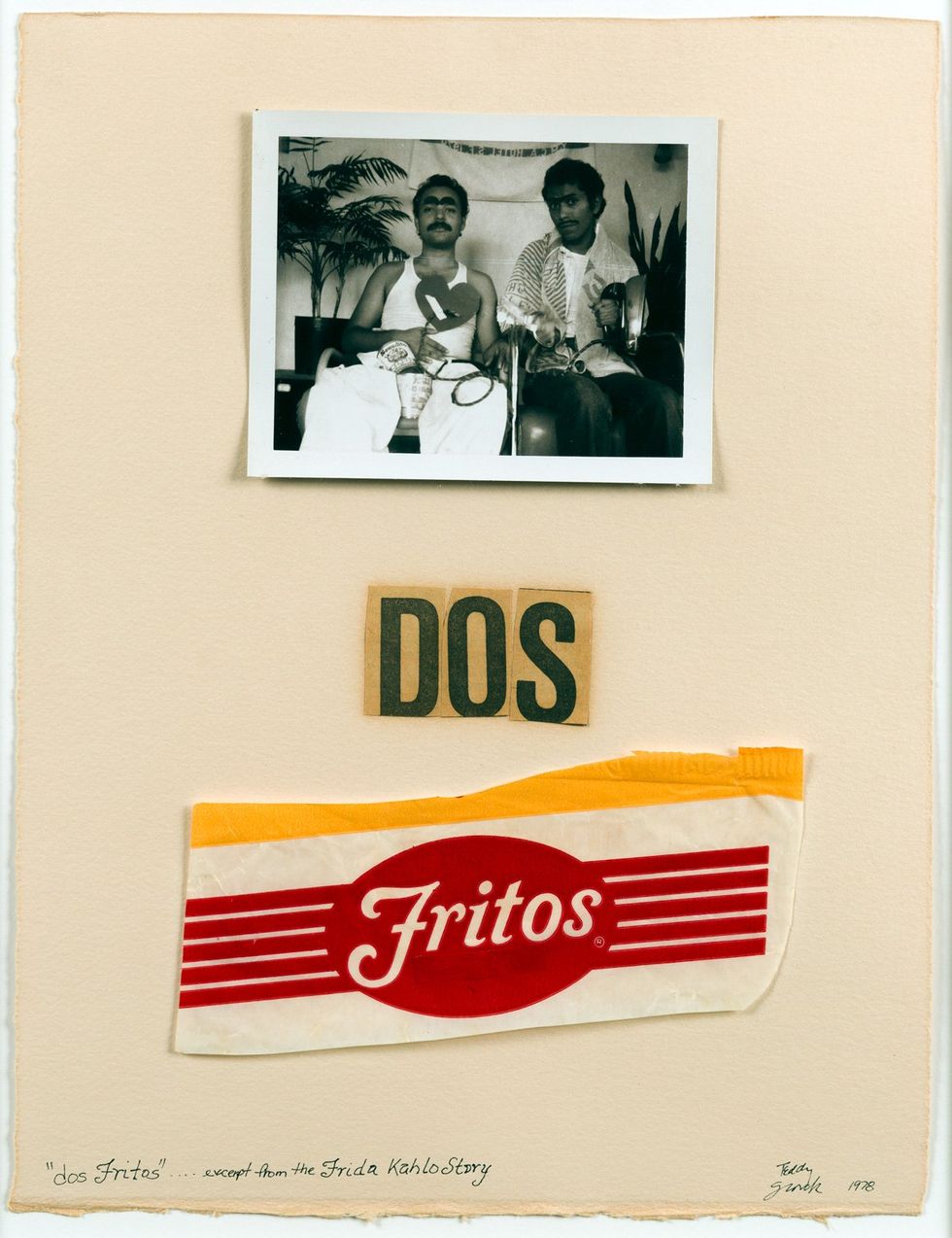

'Dos Fritos' by Teddy Sandoval, 1978

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

Sandoval’s faceless figures heighten the gay clones’ uniformity, exposing their masculinity as a kind of performance akin to drag.

While it may be tempting to view these images and his collaborations with Terrill on the zine Homeboy Beautiful through a nostalgic lens, their impact at the time was radical. By defiantly eroticizing East L.A.’s homeboy aesthetic, they disrupted and queered the patriarchal, often homophobic, Chicano visual culture.

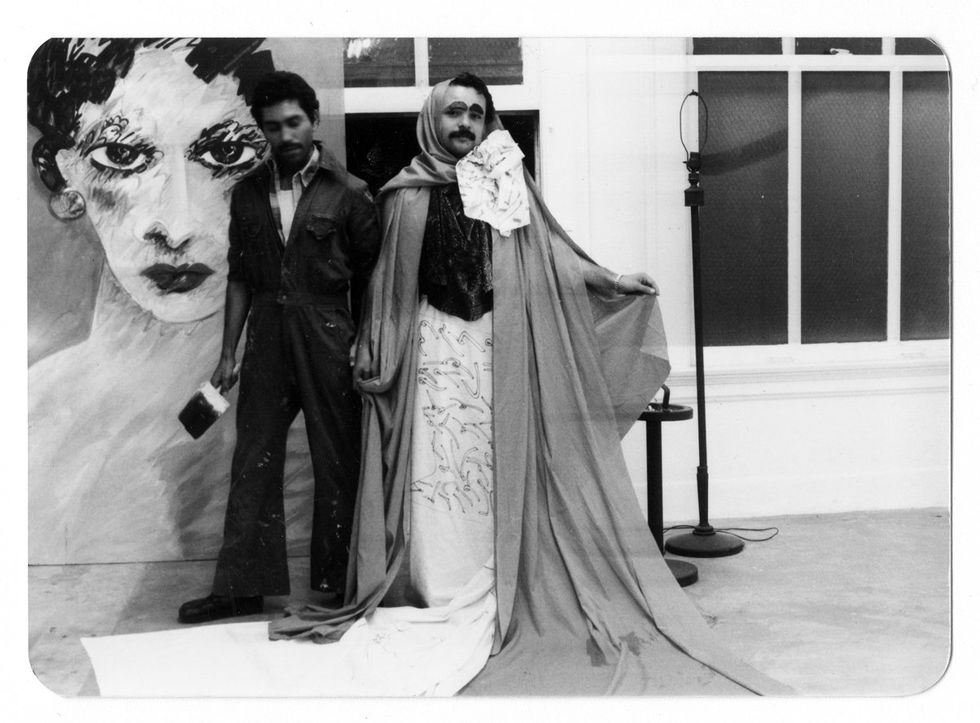

Snapshot from 'La Historia de Frida Kahlo,' a photo-performance by Teddy Sandoval and Gronk, 1978

Teddy Sandoval estate

In 1978, Sandoval teamed up with fellow Chicanx artist Gronk for La Historia de Frida Kahlo, a photo-performance that playfully reimagined the lives of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Borrowing from Mexican films and fotonovelas’ melodramatic antics, Sandoval donned gowns and high heels to portray Kahlo, while Gronk played Rivera.

Sandoval and Gronk used Kahlo as a tool to explore gender fluidity, queer identity, and the politics of performance, reframing one of Mexico’s most relevant figures as a mirror for their own irreverent, boundary-pushing art. The photographs circulated as mail art and inspired the collage Dos Fritos (1978), which honors and mocks Kahlo’s The Two Fridas.

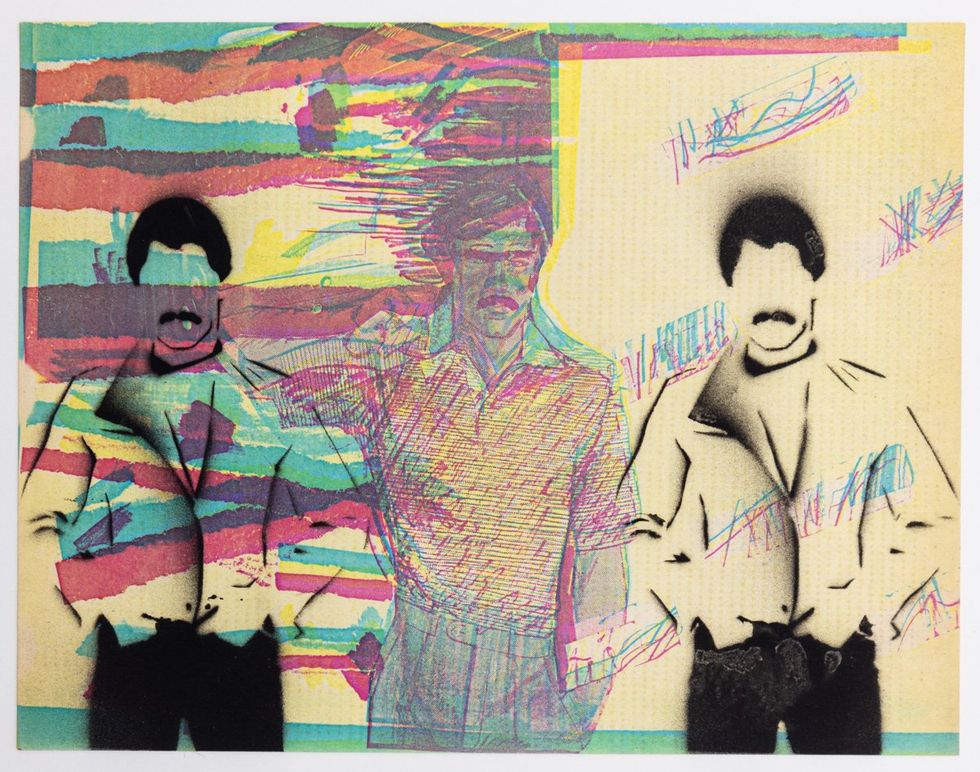

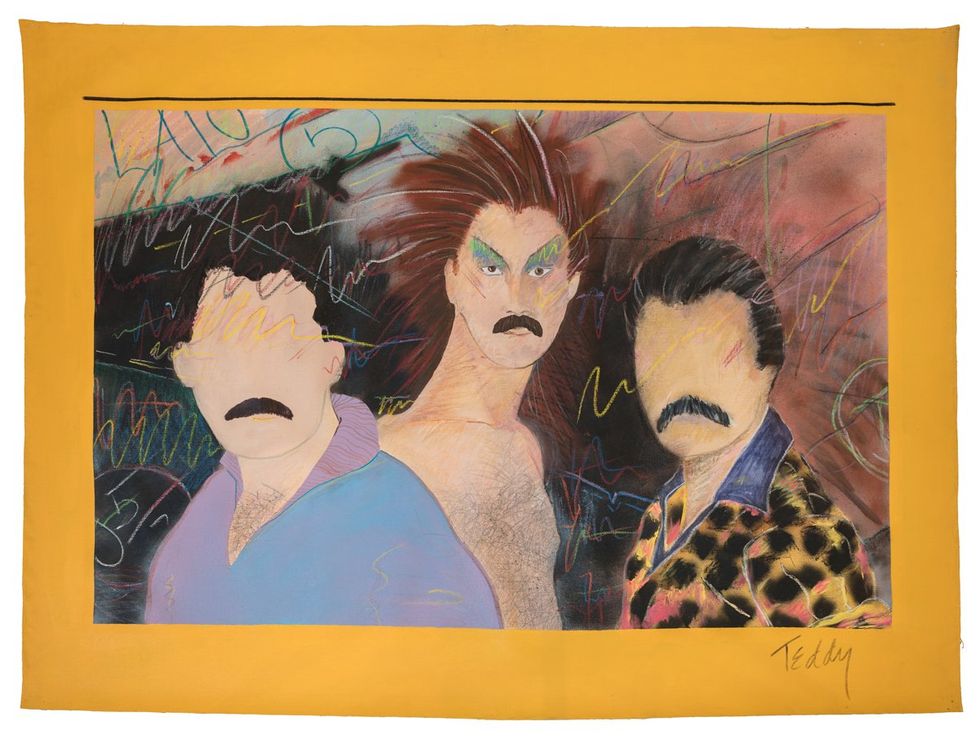

'Las Locas' by Teddy Sandoval, circa 1980

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Fredrik Nilsen

One of Sandoval's most emblematic paintings, Las Locas (circa 1980) features Sandoval on the right and his partner, Paul Polubinskas, in the center. From 1981 to 1994, the couple ran a unique ceramics company, Artquake, which produced works that regularly represented the male figure. A striking example is a porcelain wind chime featuring a naked man’s spread legs as a base that suspends dangling pairs of underwear.

Sandoval and Polubinskas also used Indigenous images as an assertion of cultural pride, featuring the Macho Mayan — a Mesoamerican warrior flexing his strong bicep while wearing underwear and a feathered headdress — as a key symbol in their ceramics.

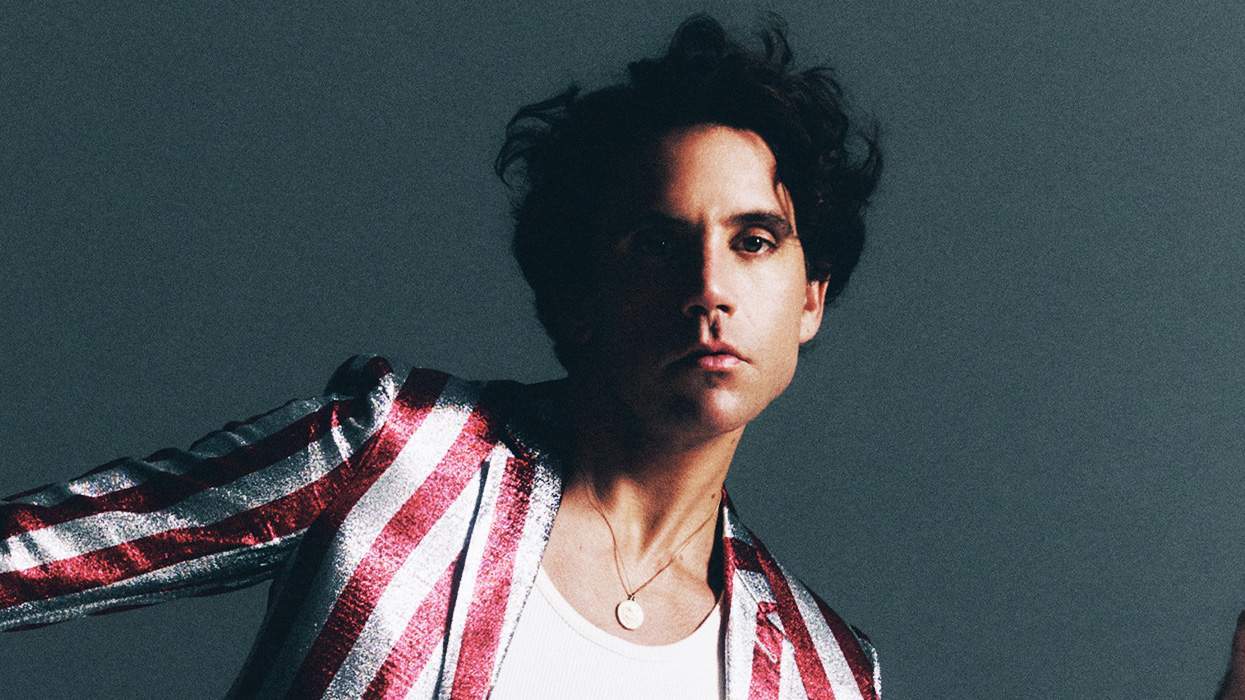

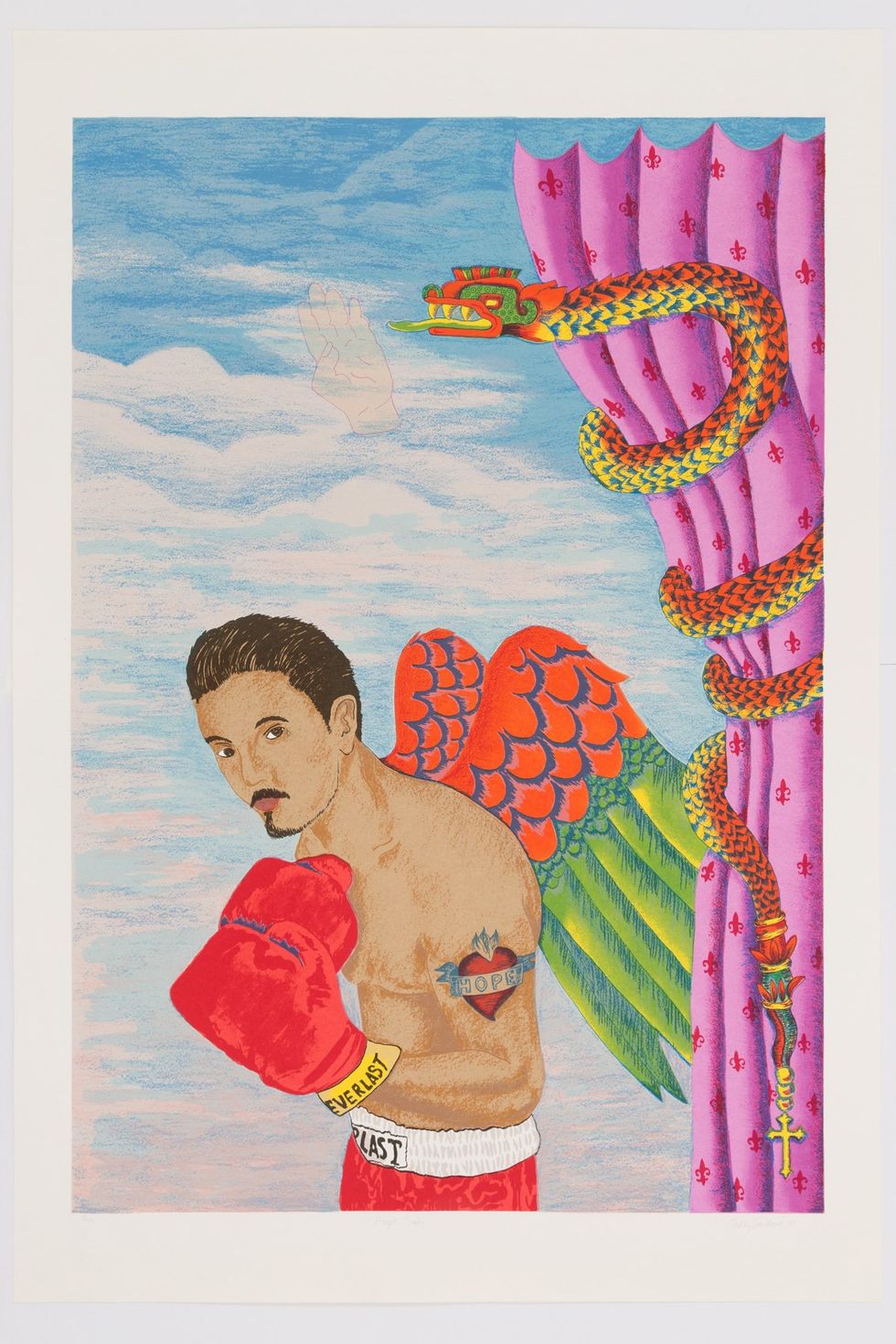

'Angel Baby' by Teddy Sandoval, 1995

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

This figure is echoed in one of Sandoval’s most famous works, the print Angel Baby, which was produced in 1995, the year the artist died. The portrayal of a muscular angel in boxing gloves epitomizes Sandoval’s world — a combination of popular imagery, Catholic and Mesoamerican motifs, cholos and male beauty. The figure’s bicep features a flaming Sacred Heart, symbolizing hope, while the brand name Everlast appears prominently on his shorts and glove.

Sandoval explained in an interview, “This image is about the concerns I have regarding violence, AIDS, war, and discrimination. We must change our thoughts within our hearts and souls if we want to live in peace and harmony.” In the print — which is as vibrant and poignant as when Sandoval created it three decades ago — the boxer becomes a guardian angel who inspires resilience during the AIDS pandemic.

'Macho Mayan' by Teddy Sandoval, 1991

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

The retrospective’s cocurators, C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz — who were also behind the groundbreaking exhibition “Axis Mundo: Queer networks in Chicano L.A” — expand the idea of the Butch Gardens School of Art by including works from 25 multigenerational queer, Latinx, and Latin American artists who share striking affinities with Sandoval. Placing their works alongside Sandoval’s underscores his enduring relevance, revealing how his playful experimentation and probing of identity and queer spaces continue to resonate across the Americas today.

Sandoval typed in one of his flyers: “Art only exists beyond the confines of accepted behavior.” We can imagine him smiling, delighted in seeing the exhibition reveal how his reach across time and space has transformed him, much like his own revered Kahlo, from a gender outlaw into a queer icon.

An interview with artist Joey Terrill

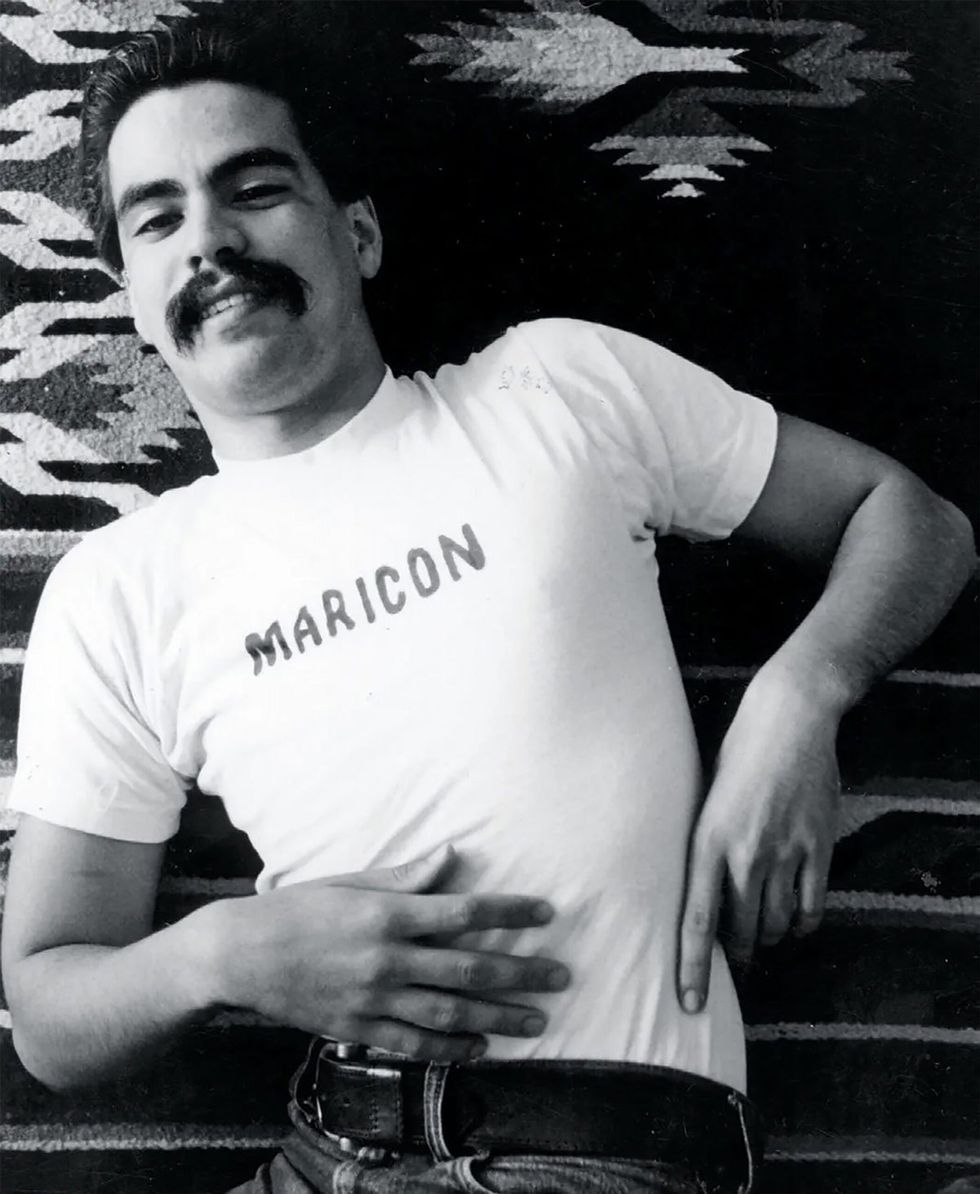

Photograph of Joey Terrill by Teddy Sandoval

Teddy Sandoval/courtesy Joey Terrill

Teddy Sandoval’s close friend and collaborator Joey Terrill spoke with Out about their work together, which spanned nearly two decades. During that time, the two worked together on projects such as Terrill’s satirical, faux-lifestyle magazine Homeboy Beautiful, published from 1978 to 1979, which critiqued American racism and aimed to erase homophobia in Chicano culture.

One of the most important Chicano artists of our time, Terrill, who was born in 1955, has worked at the intersections of queer and Chicanx identity, popular culture, and activism for over five decades. Since testing positive for HIV in 1989, Terrill has focused on personal narratives about the AIDS epidemic in his work.

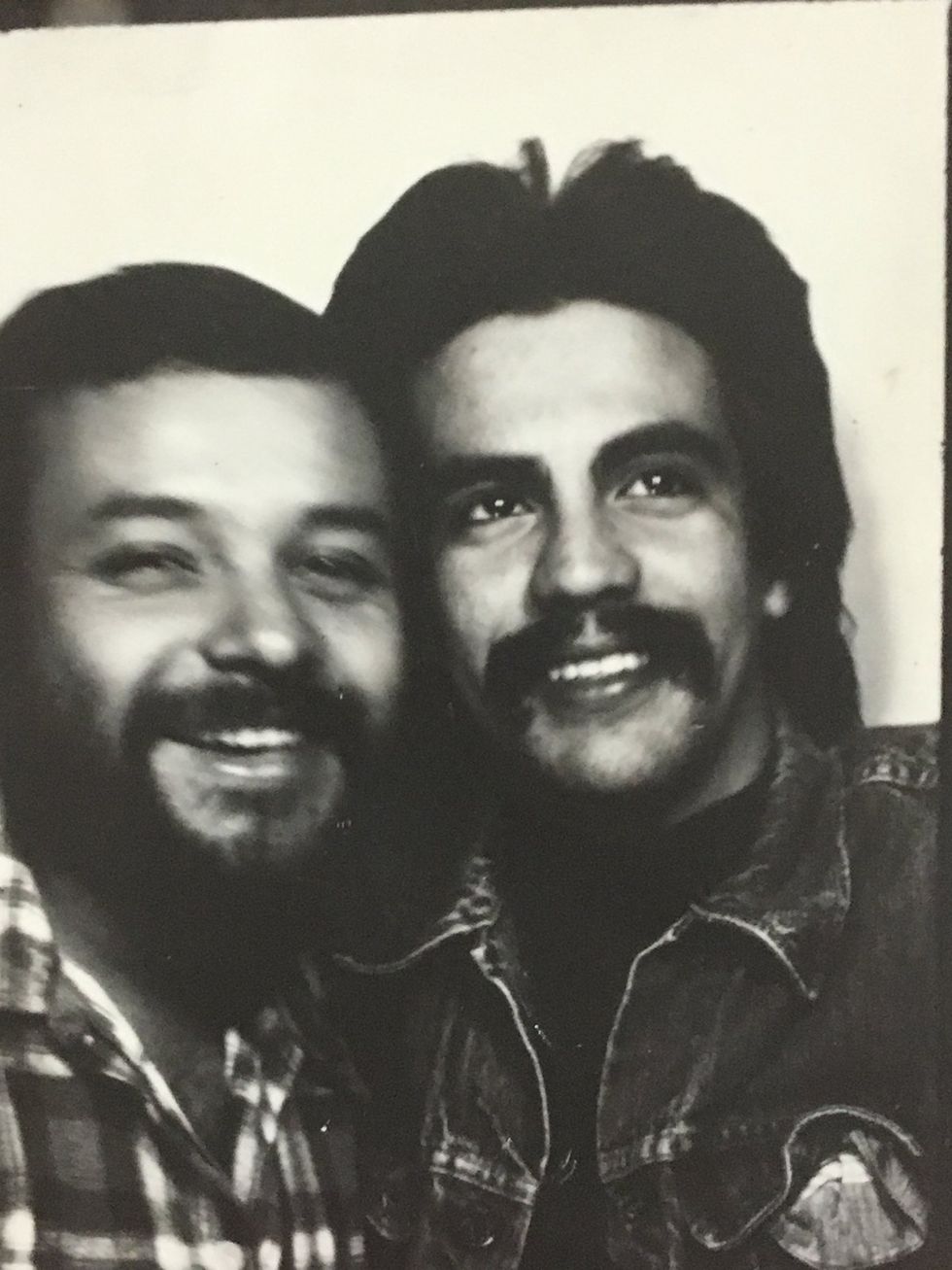

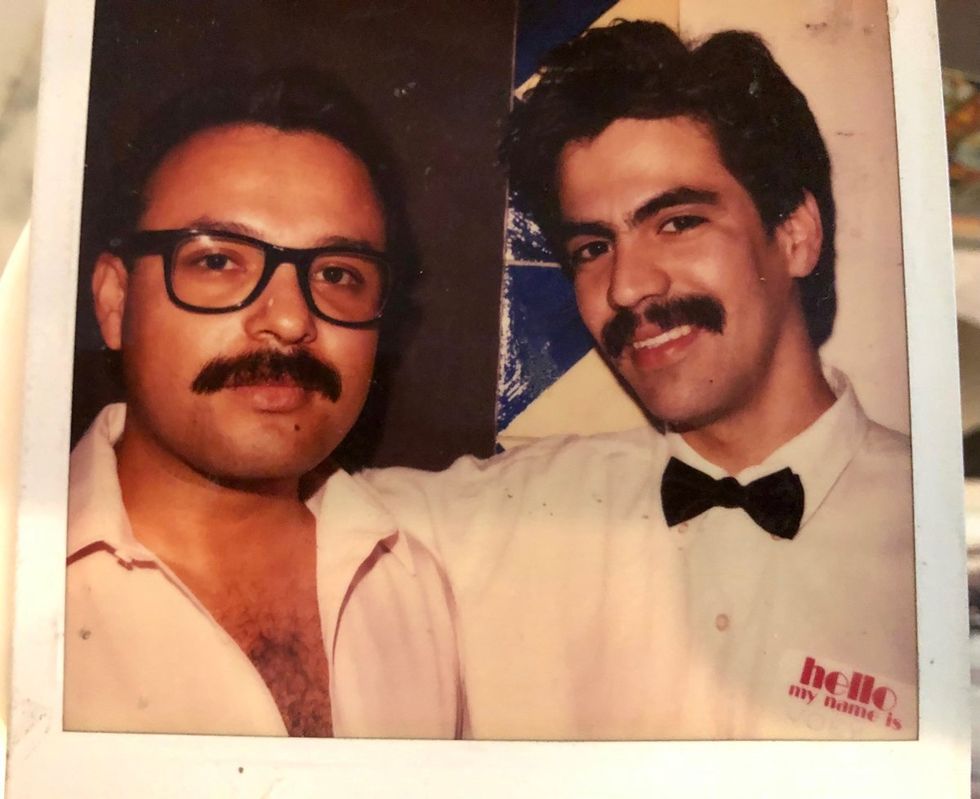

Photograph of Teddy Sandoval and Joey Terrill, 1977

courtesy Joey Terrill

How did you meet Teddy Sandoval?

JT: I had seen a small collage Teddy created showing a female nude with male genitalia at the “Chicanarte” show. It blew me away. Remember, this was the early ‘70s.

Soon after, I happened to sit next to him at an event. I told him how much I liked his work. We started chatting and continued to chat for 20 years. He was very easygoing. I loved him as a collaborator and friend. His energy and creativity stimulated me.

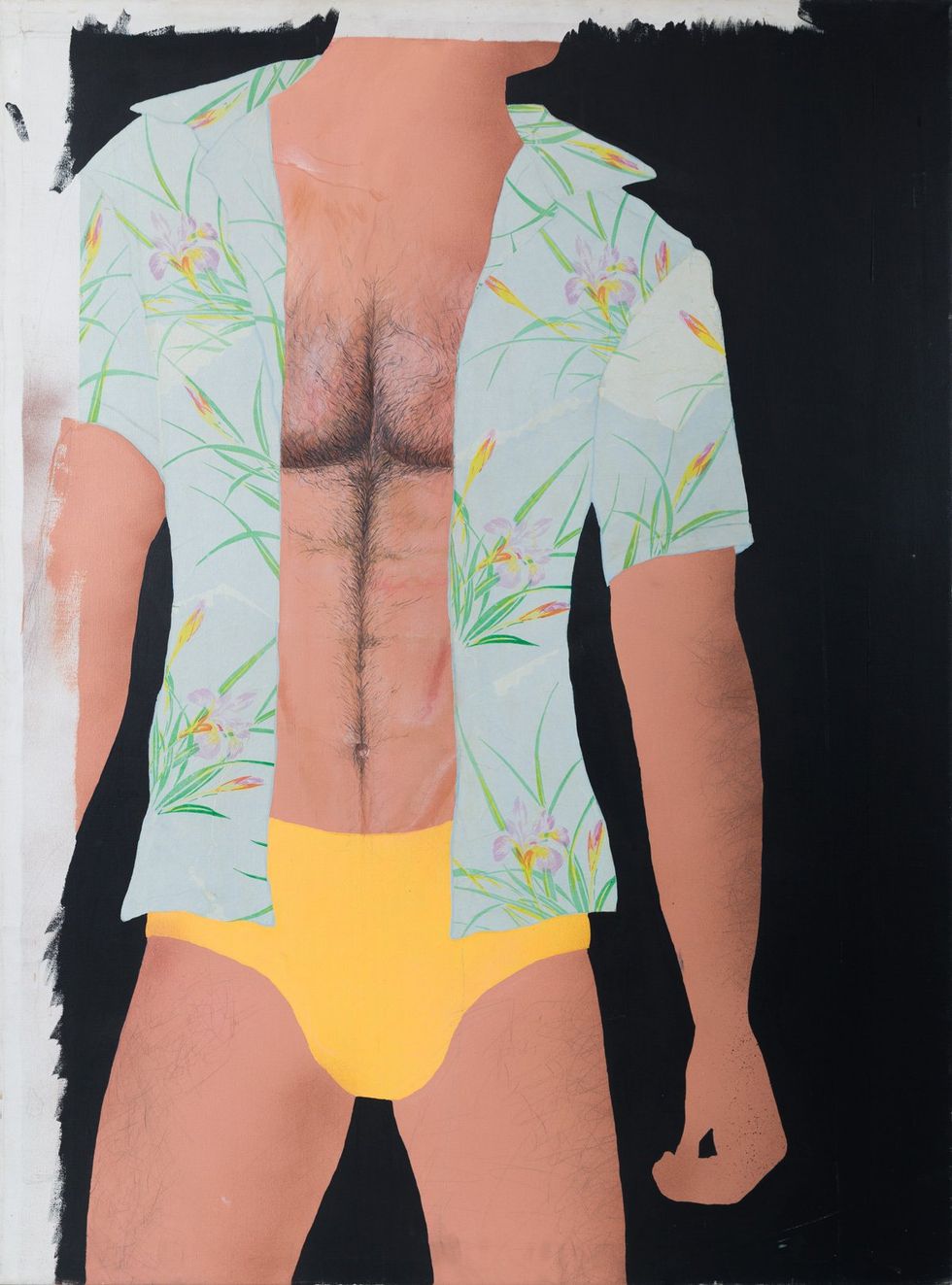

Illustration for 'Hot Tips' in 'In Touch for Men' magazine, by Teddy Sandoval, 1981

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

How did it feel going into the Butch Gardens bar?

JT: I remember walking into it and being surrounded by Latinos and cholos, hardcore hombres who loved each other. It was such a turn-on to me. I was blown away when I saw homeboys slow dancing with each other; same with homegirls. It was so romantic, especially since we had very few spaces where we could touch each other because of the machismo involved in Chicano culture.

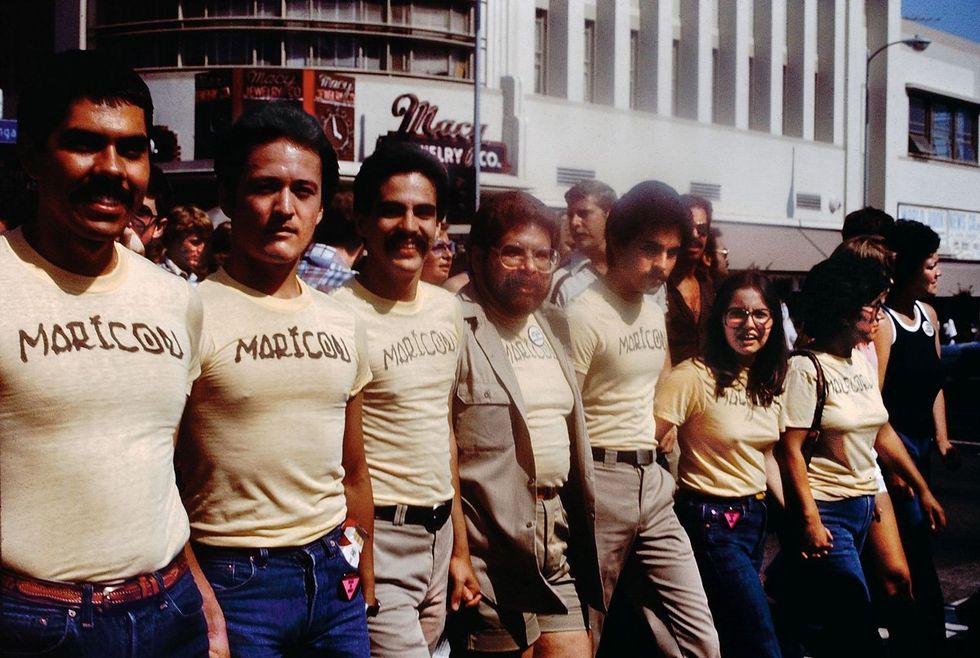

Photograph of participants at the Christopher Street West Pride parade wearing T-shirts designed by Joey Terrill, 1976

courtesy Joey Terrill

How did your collaboration with Teddy on the “Maricon” series come about?

JT: We were very invested in taking the “maricon” [“faggot”] slur, which Teddy and I got called as young men, and subvert[ing] it into an indication of pride and identity. It was a similar strategy to reclaiming the word “Chicano,” which was a slur before activists turned it into a term of Brown pride.

Teddy introduced me to the mail art phenomenon coming out of Ray Johnson in New York. We created postcards using our imagery and sent them to people all over the world. I’m sure that many of the recipients didn’t know what maricon meant.

I was working at Sears at that time and I took advantage of a promotion that allowed people to iron letters on T-shirts. I made a T-shirt with a big “MARICON” sign on [it]. Teddy took pictures of me wearing it, smiling alluringly, the opposite of a stereotypical macho pose. Then, I did a series of T-shirts saying “maricon” and “malflora” [“lesbian”]. Me and my friends wore them at the 1976 Christopher Street West Pride parade. It was such a blast. Teddy took a remarkable photo of us.

Illustration for 'The Daddy-Mystique' in 'In Touch for Men,' by Teddy Sandoval, 1981

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

You shared with Teddy a fascination with gay clones and, in your case, the erotization of homeboys.

JT: Teddy and I started poking fun [at] the clone phenomenon in our art in a good-natured way. We realized that there was a cultural shift where, instead of men coming out and proclaiming their individuality, they started adopting the same look.

It was initially subversive because the heterosexual community saw a mustached man wearing a plaid shirt and they assumed it was a brawny heterosexual. Meanwhile, we could recognize each other, with codes that denoted our sexual preferences. My mother was blown away when I explained to her that, just like pachucos and zoot-suiters would wear specific clothes to proclaim their identity, so did we.

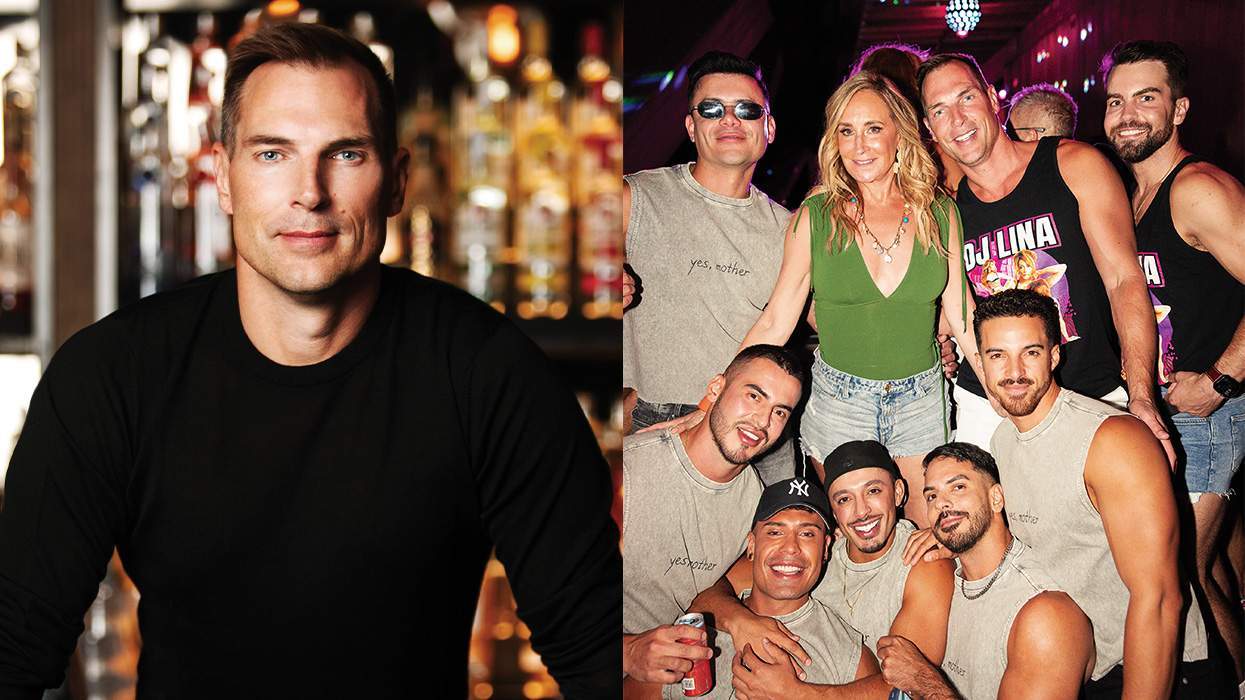

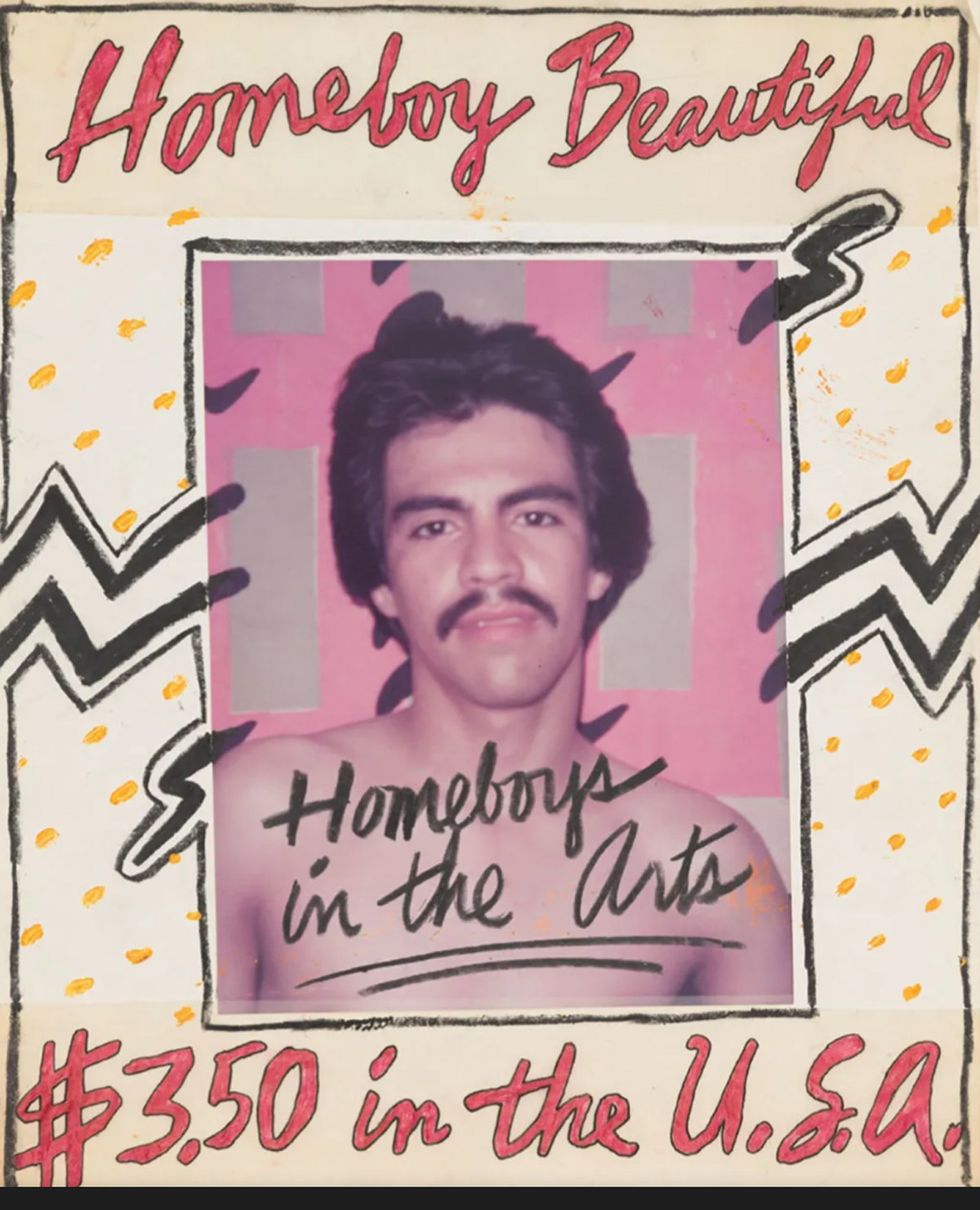

Cover art for 'Homeboy Beautiful,' circa 1978-1979

courtesy Joey Terrill

How were your collaborations for Homeboy Beautiful?

JT: I created the satirical zine Homeboy Beautiful as an extension of the “Maricon” aesthetic. Teddy collaborated with me on that. I printed and stapled the pages in an edition of 100 issues, which sold in stores like A Different Light. I liked this because it had a rebellious punk feeling, along the lines of people I admired, like John Waters [or] Monty Python, or Mad magazine.

We received thank you letters from readers saying they saw hope in it. Chatterton’s [bookstore] even organized a queer salon where people expressed their emotions and sexuality — the equivalent of what we now find so ubiquitous on social media.

'Untitled' by Teddy Sandoval, circa 1980

Teddy Sandoval estate/photo by Ian Byers-Gamber

You reframed the idea of same-sex activity in the Chicano community as male bonding.

JT: The idea that having man-to-man sex was a kind of male bonding and a vehicle to build community was in the air. It was part of the celebratory nature of going to bathhouses, which was the first time it happened in our lifetime.

Up until then, we cruised each other in public spaces. Going into a bathhouse, where we could know and have sex with each another, made us feel like our own brotherhood, not just a reflection of the heterosexual diaspora. We were always told we were different; here, we were celebrating that in a way that seemed like a political act.

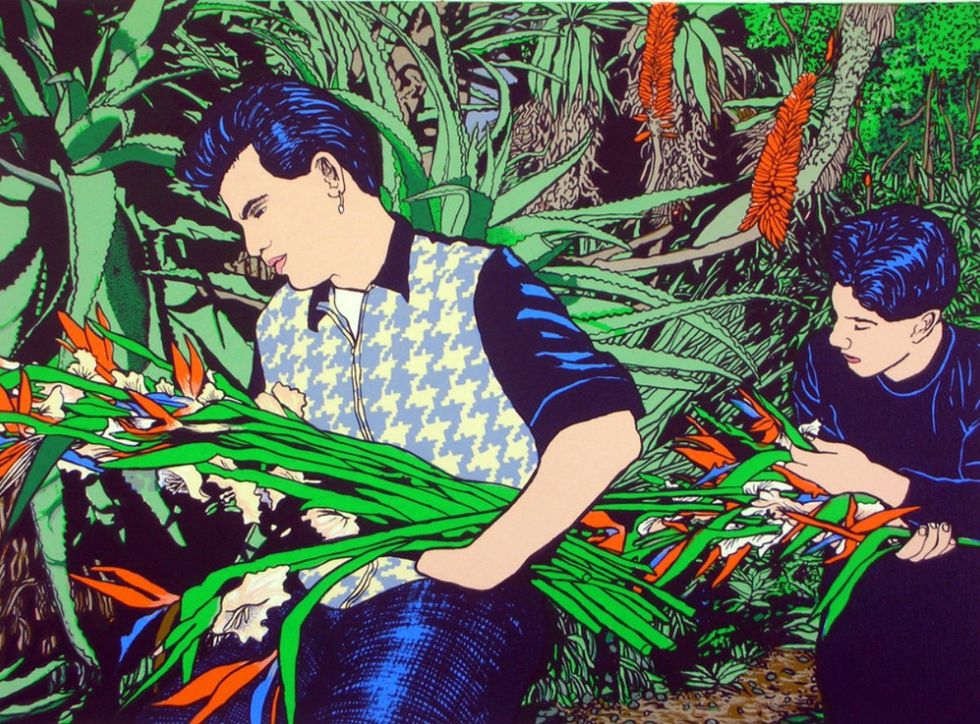

'Remembrance (for Teddy and Arnie)' by Joey Terrill, 2008

Joey Terrill

Tell me about the print Remembrance you did in Teddy’s honor.

JT: The original painting evoked our community’s grieving during the AIDS crisis. It was a very personal image for me. The scene takes place in a cactus garden because I wanted something specifically L.A. and Chicano. I show myself wearing a shirt created by my friend Arnie Araica; I used it so his design would live on. My partner at the time, Robert, stands behind me as support; he was nine years younger than I and none of his friends had yet succumbed to AIDS. I turned the image into a print honoring Teddy and Arnie.

Photograph of Teddy Sandoval and Joey Terrill, 1981

courtesy Joey Terrill

How do you think Teddy would feel about all the hoopla around this exhibition?

JT: He would be thrilled. But that would mean that he would be alive and, consequently, the exhibition itself would be totally different, because he would have had 30 more years creating art. The exhibition would have been even more magnificent.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art scholar and lecturer. You can view his Instagram, lectures, and articles on queer art history at linktr.ee/breakingthegaycodeinart.