We’re all tripping now — or at least, that’s what anyone scrolling Instagram these days might think. Psychedelics are everywhere. They’re the plotline of mainstream TV shows and buzzy documentaries, the subject of countless culture articles, and the focus of award-winning books and podcasts.

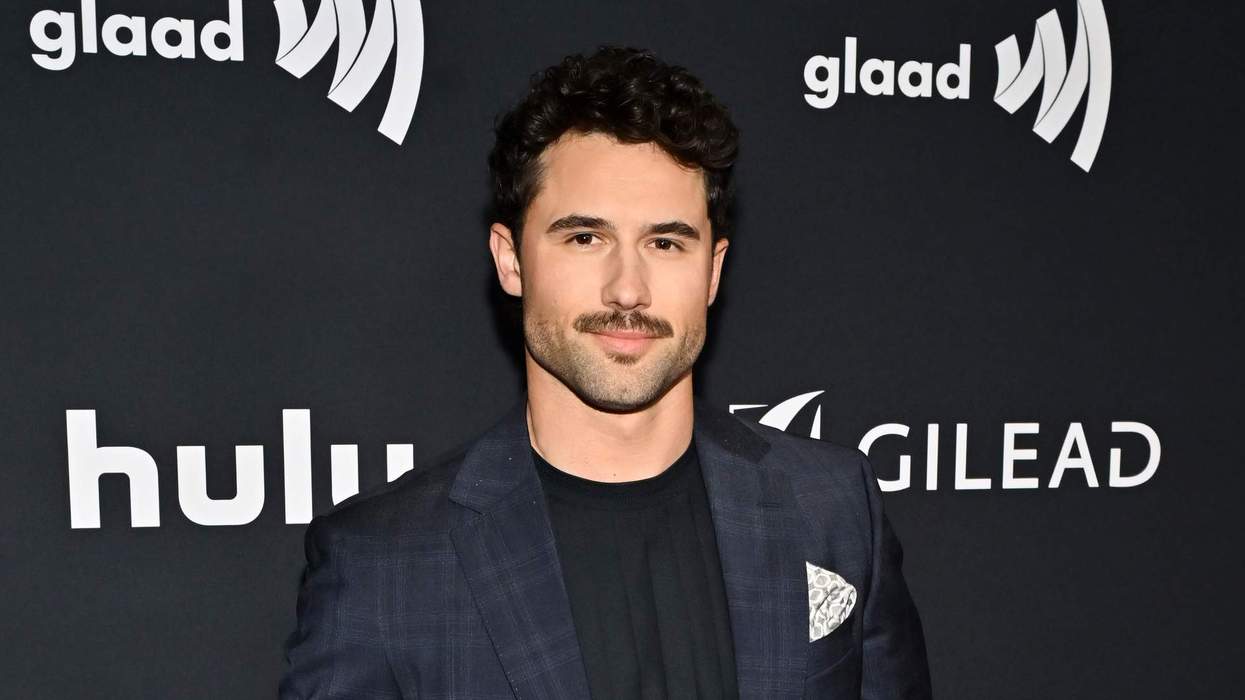

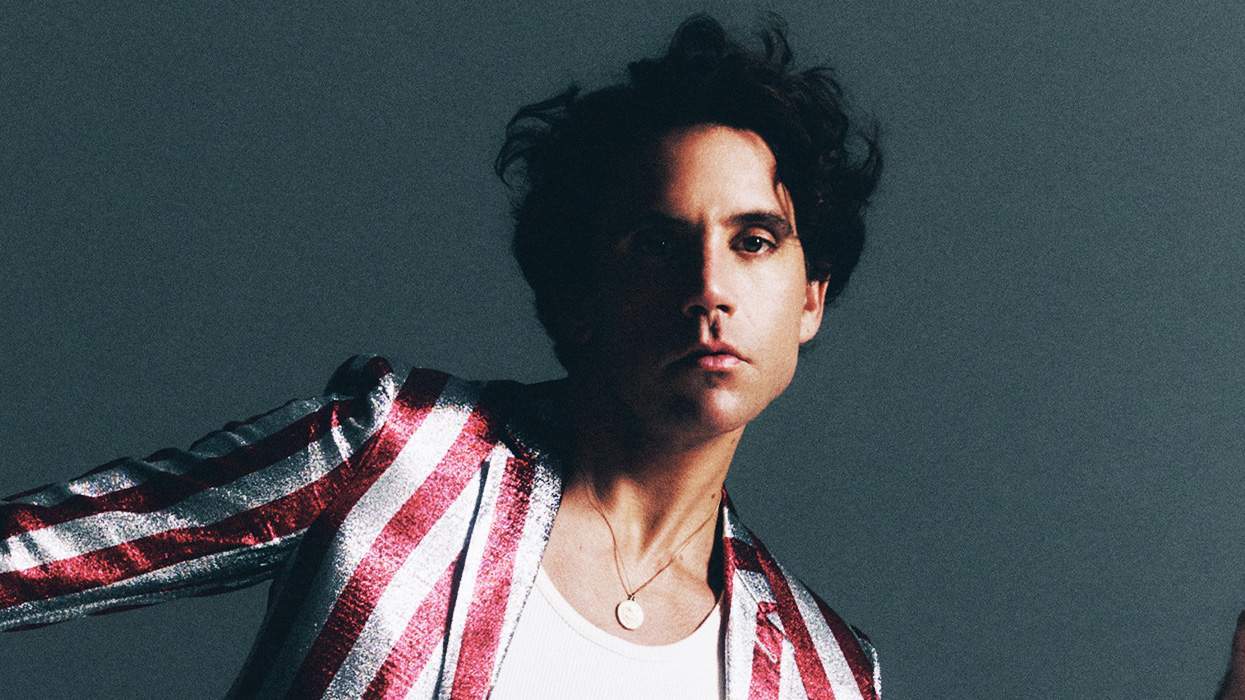

One of those books is by a gay man. Joe Dolce, a journalist and former editor of Details, has written Modern Psychedelics: The Handbook for Mindful Exploration, a plainspoken, sex-positive, beginner-friendly guide. In 2017, he published Brave New Weed, a globetrotting investigation into marijuana to “tear down the cannabis closet.” Now he’s doing the same for the drugs our culture is currently obsessed with.

Part of the reason for the new boom is clinical research. Drugs like psilocybin (the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms), LSD, mescaline (peyote), and DMT (ayahuasca) have been studied — sometimes legally, sometimes not — for decades as promising treatments for alcoholism, anxiety, depression, PTSD, and more. What were once sacraments for Indigenous peoples in Central and South America are now being slowly, tenuously absorbed into the profit-based, pharmaceutical model of Western medicine. Whether that’s a good thing is still an open question.

But one conversation I’m not seeing in legacy queer media is what this boom might mean for gay and queer men battling an altogether different drug.

Very little research has explored whether psychedelics help with addiction to stimulants, like meth. A 2025 scoping review of 132 peer-reviewed records on psychedelics and addiction notes that while the “classic” psychedelics — along with “non-classic” ones like ketamine and MDMA — show promise for people with substance use disorders, the evidence is strongest for alcohol and smoking; evidence for stimulants is described as “preliminary,” “mixed,” or of “lower quality.” Even so, it should be explored.

Meth has carved the deepest trench in modern gay life. If there’s any substance my community needs help with, it’s this one. I wonder if meth is so tied to gay chemsex that it’s too niche, too messy, too gay to attract serious research interest. In the arena of life-threatening drugs, meth isn’t the deadliest: Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that of the hundreds of thousands of drug-related deaths in the U.S. each year, roughly 80 percent are from opioids like fentanyl. Meth is more likely to make you miserable than kill you.

And misery is harder to measure. Medicalizing something as nebulous as a psychedelic trip and reducing it to symptom scores and end points narrows these compounds into tools of last resort — for people at risk of dying — rather than things that might simply make us a bit happier, a bit better.

The need for something to help gay men fight meth is real. Stats are grim. Federal survey data from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration show that about one in three gay and bisexual men meet criteria for a substance use disorder each year — roughly a third more the rate of straight adults. Across Europe, there’s no pan-EU LGBTQ+ dataset, but city-level work from London to Amsterdam finds that gay and bi men are five to 10 times likelier than straight men to use mephedrone, GHB, ketamine, and crystal meth. Health agencies in London, Stockholm, and Amsterdam all report the same trend.

In Berlin, my home, a 2018 report from Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe puts it plainly: “Chemsex in Berlin is primarily a phenomenon of gay and bisexual men.”

Before Berlin, I lived in New York City, and my drug use was becoming too much. Not severe — not yet — but bending in the wrong direction. When COVID-19 lockdown hit, my friends baked cakes and started podcasts, and I decided to fix my relationship with meth. I already had a harm-reduction therapist and meditated daily, but neither of these was new. And still, there was meth.

I wasn’t a heavy user, but I used it enough to see the slope I was on. My risk of dying was low, but my risk of building a life of hollow, sporadic, disconnected sex was high. I wasn’t the guy who binged for days; I disappeared one weekend a month, fucked dozens of strangers, and came back on Monday without losing a job or missing a deadline. That kind of functioning is its own trap: You can do it for years and still lose the thing that matters most — your natural desire.

I could feel mine slipping. The link between getting turned on and getting high was fixed — meth had a grip on my sexuality, and even though I wasn’t in free fall, I knew where my life would go if I didn’t change. So I got help. But what I didn’t tell my therapist at the time, because I didn’t think it mattered, was that I also started experimenting with psychedelics.

Over a few months, I did several strong, “hero dose” psilocybin trips with a friend. After each one, we talked through what I’d seen and felt. It wasn’t structured, and my friend wasn’t a therapist; it was just an adventure. During one strong trip, I asked him to wait outside the room. Inside the room was a large mirror. I sat in front of it.

Mushrooms can create dissociation — I felt like I was meeting myself for the first time. I even said “hello,” like greeting a stranger. As I sat and looked at my body, I began to understand something: My only real job was to love this person and protect him. Like keeping dangerous food away from a dog, I had to keep the bad stuff (meth) out of reach, even when he wanted it, because this was my responsibility, no one else’s. If all I did in a day was love this man — this body, this face looking back at me — it was enough. That was the job of my life.

I don’t believe in single-moment epiphanies. This was part of a long chain: therapy, meditation, and these strange, shimmering drug experiences. Together, they created some distance between me and meth, enough to finally look at it and shrug: It’s fun, but not this time.

Since COVID, psychedelics have exploded into mainstream culture. But among my gay and queer friends, opinions are still split. Men in recovery see psychedelics as forbidden. For party boys, psychedelics are just rave enhancers. The idea of using them for healing feels like it belongs to a heterosexual cultural frame — tech bros, hedge fund dads, wellness influencers. It seems to me that many gay men who could benefit from them dismiss the whole thing as a fad.

If anyone is curious, read Joe Dolce’s book. Unlike many books on psychedelics, which get preachy, his is a practical guide — no questionable spiritual stuff, no cosmic sermon, just clear, grounded information on doses, safety, what to expect, how to choose a guide, and what to do if things go badly.

“I wanted to write a book for people who want to understand these compounds without having to buy into a belief system,” he says. “I had to keep the tone measured and frank because a lot of folks, especially queer folks with religious trauma, shut down the minute you get mystical.”

His goal was to “put the tools in people’s hands and let them decide how to use them.”

Joe is a regular psychedelic user but not a meth expert. For that, I turned to someone whose story, we discovered, mirrors mine.

Dr. Dallas Bragg is a therapist who runs a thriving online recovery practice for gay men trying to stop or reduce their crystal meth use. He tells me he has so many clients that “there could be 10 of me and it wouldn’t be enough.” Like mine, his recovery crossed paths with psychedelics.

His first breakthrough came with psilocybin. “It cut right through all the trauma, all the limiting beliefs,” he says. “It silenced it all. Then there was just me. I experienced what I am underneath all that. Suddenly, I was in this place of unconditional acceptance and love.”

During a later ayahuasca ceremony, he felt something similar and deeper: “I felt connected to others, connected to the earth. There was a connection and an interdependence with nature that I never knew existed.”

He’s clear that the experience didn’t “cure” his addiction — all it did, in his words, was change his orientation to himself. “It wasn’t about recovery anymore,” he says. “It was just about healing. Meth fell away naturally because it just wasn’t part of that.”

Dr. Bragg is frank about the limits — psychedelics do not fix a life. They don’t untangle trauma by magic. They also don’t work, he says, if someone is still actively using meth, and he’s clear with clients: “Let’s get the chemical out of your system first. Then we can get true results.”

Should people with substance use disorder worry about getting hooked on psychedelics? Dolce’s book — along with the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Journal of Psychopharmacology, and the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research — all point out that most research suggests the classic psychedelics are nonaddictive. Dr. Bragg is more cautious.

“Some folks keep going back,” he says. “It may not be a chemical addiction, but it does become another escape, especially when there’s no integration.” But he sees real potential if psychedelics are used alongside other supports: “I do believe it will help.”

If a gay man struggling with meth approached him and asked if psychedelics could help, his answer would be a cautious yes — as long as a therapist and proper integration were built into the experience.

Like me, Dr. Bragg is not a 12-step guy — mostly because of negative early experiences with religion as a gay man. “It felt like being back in church,” he says. “There’s only one true book and only one true way. You’re powerless. You’re defective.”

For many gay men, he says, shame is the root wound, not the cure — and 12-step felt like a system that deployed shame. Instead, he advocates a harm-reduction model: no chips, no day-counts. Sometimes he even helps clients plan controlled, measured usage on weekends.

“When they get six months away from meth, I tell them it’s OK to plan a reward weekend,” he says. “Most of the time, after six months of feeling great, they just don’t want it anymore.”

He sees something I’ve seen, too: The stigma around sober sex — and gay sex in general — pushes people to meth in the first place. “Porn has taught multiple generations that bottoming has to be pristine,” he says. “Meth gives you confidence you haven’t learned how to develop on your own.” Add shame, poor sex education, and deep isolation, and meth becomes a crutch for men to experience the kind of intense sex they see online and think is required for a happy sex life.

So what could psychedelics offer this world of shame and spiraling drug use? Maybe what they gave me: a moment of clarity, a little distance, a little self-love. Maybe what they gave Dr. Bragg: a sense of interconnectedness.

Psychedelics won’t save everyone — and they won’t replace therapy. They won’t undo the cultural forces that make many gay men struggle with drugs in the first place. But for some of us — and, I believe, for many more of us — they just might open a kind of door. Call it a mystical experience, a fungus, a drug, whatever, but on the other side of a trip, countless people have found healing and hope. Maybe it’s time for my people — my party guys, my tweakers, my crystal cowboys, the men I love most — to give it a try.

Alexander Cheves is a writer, sex educator, and author of My Love Is a Beast: Confessions from Unbound Edition Press. @badalexcheves

This article is part of OUT’s Jan-Feb 2026 print issue, which hits newsstands January 27. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Apple News+, Zinio, Nook, or PressReader.