There's been a lot of talk lately about what Chicagoans should do in the face of rising political hostility toward our community. Now more than ever, we need a reminder of what still brings us together, what still makes us strong.

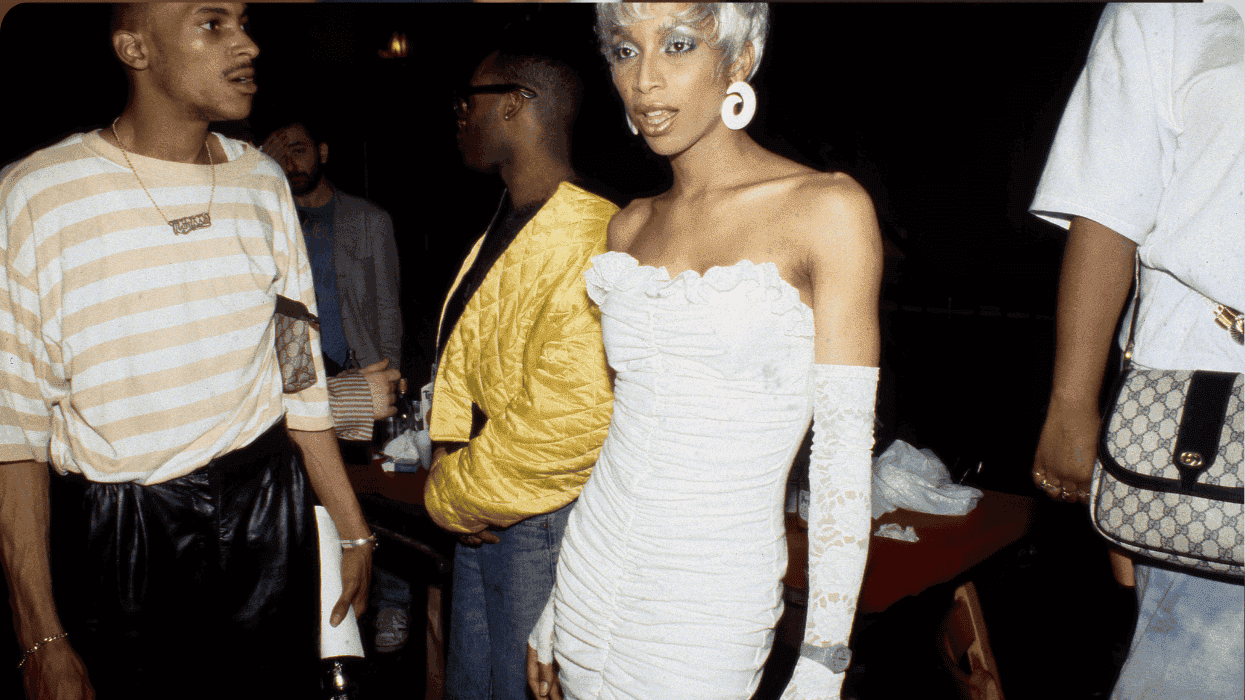

For me, that reminder came on a crowded dancefloor at Market Days in Chicago, under the lights of CircuitMOM!.

I will never forget the first gay club DJ I saw in Indianapolis, Indiana: DJ Deanne. Back then, in the Midwest club scene, she was already a legend—someone who could fill a floor from the first beat and keep it moving until closing. Fiona Buckland describes mnesis in nightlife as a complex fusion of personal history, music, and movement. That interplay was on full display when I watched her perform at CircuitMOM!.

In my late 20s, her music became my coming-out anthems; now, in my 40s, it calls upon me to reflect on my life as unapologetically queer. Even back then, I was different from other gays—my gothness, my aloof personality—and little has changed in that regard. But what has changed is my ability to see and appreciate beauty in all things: the soft glance of a stranger across the dancefloor, the perfect sync of a fan clack with a bass drop, and the quiet intimacy that exists even in a crowd of thousands.

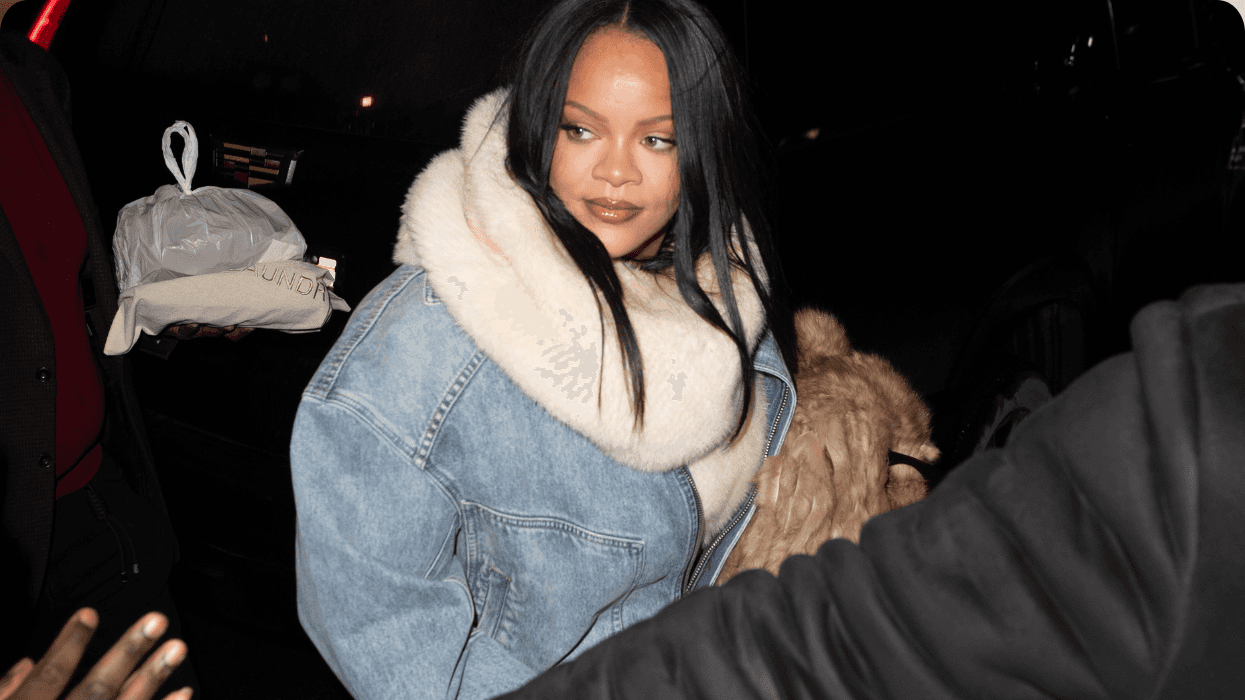

Market Days has a storied place in Chicago's gay history. Established in 1982 by the Northalsted Business Alliance, then a coalition of small business owners in what was, and remains, Chicago's Boystown, the festival began as a modest neighborhood street fair showcasing local shops, bars, and artists. Over the decades, it grew into the largest street festival in the Midwest, stretching along North Halsted from Belmont to Addison and drawing more than 200,000 attendees. It became not only an economic engine for gay-owned businesses but also a cultural anchor point in Chicagoland's gay life and an intersection where music, performance, and politics intermingle in the open air.

CircuitMOM! is one of the weekend's marquee events, translating the festival's street-level energy into an immersive nighttime performance staged at venues like the historic Aragon Ballroom. "CircuitMOM! has always been about more than music," founder Matthew Harvat told me. "It's about creating a space where people can live their truth out loud, without apology. If we can give people even one night of feeling fully themselves, then we've done our job."

Like any other subculture, circuit-goers create hierarchies rooted in authenticity, translating subcultural capital into both social and economic capital. For the uninitiated, circuit parties are the gay world's answer to rave festivals. While both share roots in underground culture, they've evolved into distinct scenes, serving different audiences with different traditions. At their core, both are about letting go and expressing an unfiltered, authentic self within a large-scale spectacle.

One defining difference between raves and circuit parties is the age diversity in the gay circuit. Because gay people rarely have spaces where we can fully express ourselves, these events become both a party and a collective performance of survival and belonging. They are also mirrors, reflecting to us the different selves we have been, and showing us the selves we are still becoming.

That sense of recognition carried into the moments between songs. Despite being in a major city, I was reminded how small the gay world can feel. I ran into people I knew from my travels and from my fieldwork: folks from Las Vegas, Indianapolis, Washington D.C., and, of course, my current home of Kansas City. Those brief reunions weren't just social niceties; they were reminders that this network of faces, bodies, and histories is what we have built in the absence of full societal acceptance. It was, after all, partygoers—not the federal government—who traced their own contacts to slow the spread of monkeypox, just as Kansas City's community leaders once stepped in to care for people with HIV and AIDS when institutions failed.

While there are criticisms of these events as homogeneous spaces, there was real diversity in the room. One of the dancers was a Bear. Women, though not in significant numbers, were present. Ages varied among the revelers. These shifts reflect a broader transition from gay spaces to more inclusive spaces, a change Greggor Mattson has written about as both an economic necessity and a cultural evolution.

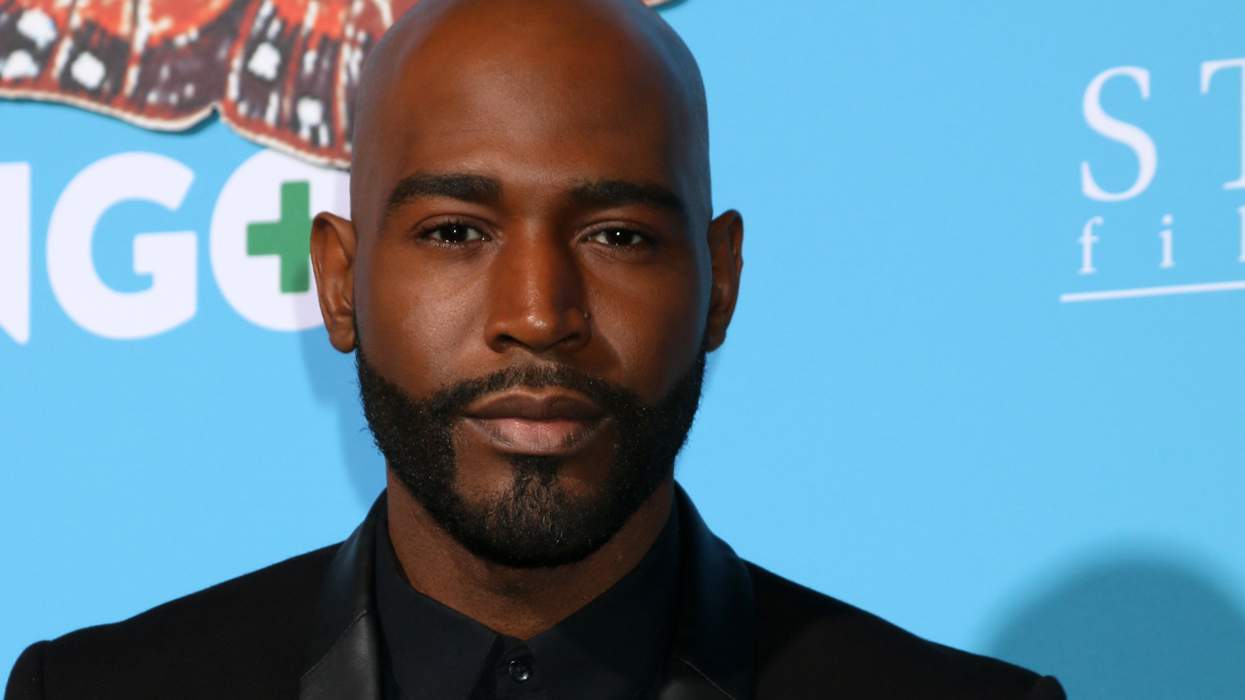

Of course, not everyone is thrilled about this shift. The loudest resistance often comes from gay men my age or older, many of whom reject the word "queer" outright. At the core of their discomfort is an anxiety that they will no longer be catered to, that they will be forgotten. The Trump administration's quiet removal of "queer" from official spaces like the historic Stonewall National Monument was a reminder of how language signals political alignment. For some, "queer" is a rejection of assimilation into dominant culture. For others, it is a bridge too far. But as I stood in that ballroom, I realized our history has never been about perfect agreement—it's been about showing up for each other, even when we disagree, and keeping the music playing.

Events like Market Days and CircuitMOM! aren't just parties. They are declarations that say we are still here, we still dance, and we refuse to be small. In a moment when political forces are working hard to erase us, there is power in bodies pressed together on the dancefloor. That is what gay joy looks like. Not a distraction from the struggle, but one of our oldest and fiercest forms of resistance.

Christopher T. Conner is the Stephen O. Murray Faculty-in-Residence at Michigan State University.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.