Growing up as a gay Black and white kid in rural Missouri, I learned that speech can tell you so much about a person. At home and online, I listened to friends and classmates toss snippets of Black queer slang they picked up from TikTok.

"OMG, slay queen! We finna be outside tonight!!!" One of my white friends would often say. Her ignorance now echoes in my transition to Columbia University. I hear the same hodgepodge of words and catchphrases from people who are neither Black nor queer. Both here and home, they get laughs for sounding "funny" or "plugged in," while the histories of these words are treated as irrelevant. Non-Black, and often straight people, turn Black queer slang, a language shaped in Black queer spaces like ballroom and the Black gay South, into a cheap punchline, exploiting a culture they often disregard. My language is not their backbone when their own jokes are not enough.

A Twitter user and Ariana Grande stan once said, 'When the chile is tea, but the finna is gag, sis I'm dead as a chile.' That one sentence, posted by a user named @yasscorset, set off a flood of quote-tweets, screenshots, and reaction videos. People labeled it the 'patient zero' of Black Nonsense, a term used online to describe the chaotic misuse of AAVE and Black queer slang. On the surface, it is funny, but only because the sentence fails so much at making sense that it feels like pure irony or satire. Its virality shows how people use random Black queer terms as a shortcut to manufactured humor. But the joke only works because Black queer language has already been stripped of its history and turned into a crutch for white, straight peers and influencers who fail at authentic humor.

I've seen this phenomenon with my friends here on campus. One night, my friend Niomy told me she was joking around with men on Omegle, asking them if they were "studs" just to mess with them. We laughed, but when I asked her what "stud" actually means, she shrugged and admitted she knew nothing and thought it was just funny. For her, "stud" was just another word to throw around, not a term rooted in Black lesbian communities to describe a specific kind of Black masculine woman. That moment makes clear how easy it is for non-Black people to reach Black queer language as a joke and drop it as quickly as it was questioned. Her disregard stung, demonstrating how disposable our language becomes when stripped of the community that gives it life.

When users run out of things to say, they recall "Gen Z slang": chile, tea, finna, gag, sis. But Black queer expression, as scholar E. Patrick Johnson has argued, has long been consumed as entertainment by people outside the community, even as the people behind it remain marginalized. They plug these words and other phrases into incoherent sentences and pray the rhythm of Black queer speech will take the place of an actual joke. That laughter is a signal that the erasure of Black queer history is being ignored, and an entire community's linguistic creativity and expression is compacted to a punchline and nothing more. Its spread also reflects the compelling and innovative nature of Black queer expression, even when people refuse to honor its roots. By reducing a lived reality into a set of trendy sounds, it shows how commodity culture prioritizes using marginalized identities as jokes instead of listening to the people who live them.

Granted, as trends become more influential, it may become difficult to trace what you're saying to its cultural roots. That being said, you wouldn't use a word someone taught you before you knew what it meant, so what makes the context of modern word use any different? Black queer language is a record of who we are and how we've survived — it deserves more than to be treated like a punchline. This single issue speaks to a larger cultural pattern of treating Black queer life as content, not community. When our language becomes nothing but a joke, it teaches people to see Black queer life as aesthetic, not as something real, complex, and at risk. If language is a memory of how Black queer people have survived, then treating it as disposable means treating us as disposable too.

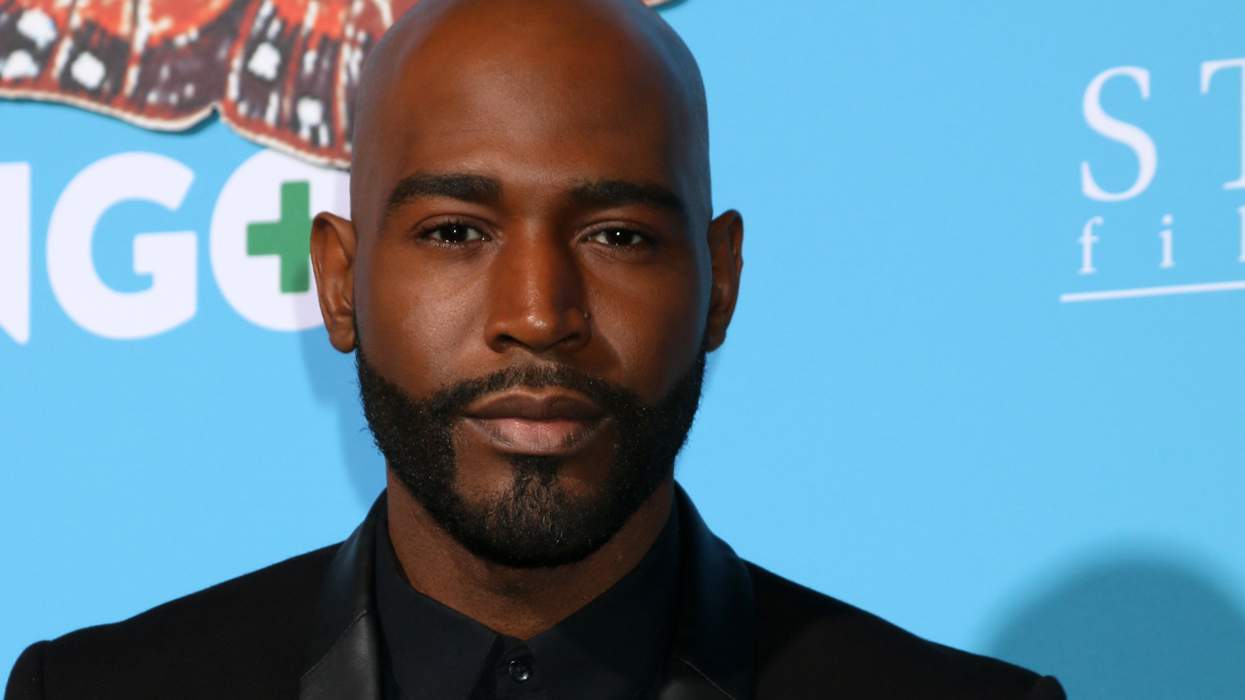

Quincy Hartwigsen is a 19‑year‑old gay biracial student from rural Missouri and is currently an undergraduate at Columbia University.

Opinion is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Opinion stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.