As I constantly told myself while writing this: “Don’t do it, girl. Don’t do it.”

Well, I did it.

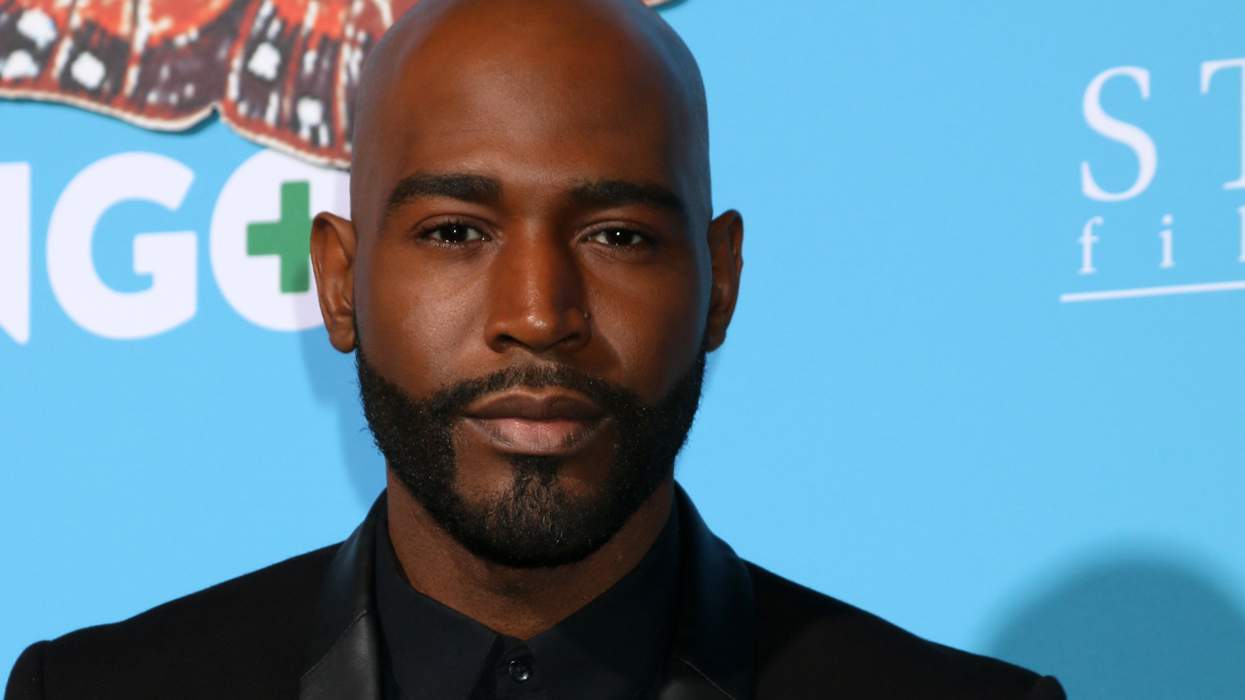

As the press tour for the tenth and final season of Netflix's Queer Eye began, the show's culture expert, Karamo Brown, pulled out of all guest appearances and interviews with his fellow cast members. When the cast appeared on CBS Mornings, Karamo's absence was loud and clear, with the star sending in a pre-recorded video with a statement of dealing with emotional and mental abuse on set, choosing to distance himself to maintain his peace. Netizens were quick to speculate on what really happened, though TMZ reported that the fallout allegedly began when fellow cast members trash-talked Karamo with their mics still on. Karamo's mom allegedly overheard it while on the set for a day and later told him.

Sadly, Karamo's experience with The Fab Five is an experience many Black queer folks face at some point in our lives. Whether it's at our jobs, the social spaces we inhabit, or the homes we're in, Black queer folks navigate a field of mental and emotional abuses because we exist in spaces designed to deny us.

Over the years, my career has taken me into professional fields centered around whiteness. In the past decade, that has included an art museum and a philharmonic orchestra. An ad agency and, of course, a LGBTQ+ media company. Though each space proclaims itself inclusive in what it offers the public, that diversity doesn't always align with its internal structure. It felt like an uphill battle to get workplaces to partner with "urban organizations" (read: Black-centered). Defending why certain voices shouldn't be prioritized solely during cultural awareness days, weeks, or months, only for us to go back to our regularly scheduled production to cater to overwhelmingly white audiences. Being one of the few others in the workplace–Black and/or trans, take your pick–it was hard to find someone whom I could talk to about microaggressions at the workplace, as so often these actions were swept aside by white managers and overlooked by HR officials. Or, conversely, presumed aggression toward coworkers. I'll never forget an accusation of being assertive and aggressive in a group text. A. group. text.

Thus began my predilection for always keeping receipts.

So, how does this Black trans professional unwind? Usually with a martini at a local gay or queer bar. Still, there's silent aggression in these spaces. As much as gay, queer, and drag bars promote themselves as inclusive, there's no doubt that many remain centered around white gay men. Or, worse, the straight women who come in and treat it like it's a petting zoo. Whether I'm at an establishment in my neighborhood, in WeHo, or Hell's Kitchen, these spaces remain catered to white patrons and, with it, their tastes and preferences. And as the night whispers and the music grows louder, patrons rush in with nothing but smiles and biases.

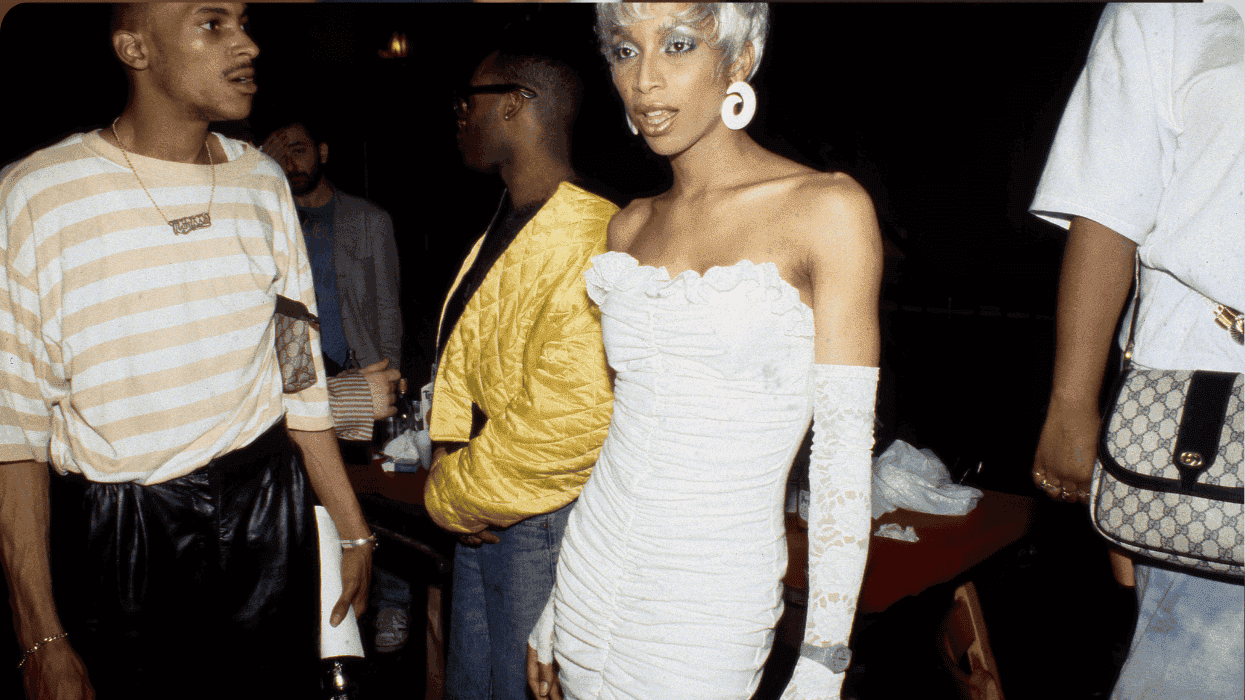

In the physical and digital spheres, Black queer and trans folks face ridicule for how we present ourselves to the world. Whether it's the way we talk, how we dress, or how we hit the pavement, we're often derided for existing proudly and comfortably in our skin. We can be critiqued for being either too feminine or masculine, or the not-so-subtle jab about how our hair looks different on Friday than it did on Monday. But the very same critiques are celebrated when repurposed and reused. "Gen Z slang" is nothing but the lingo used in Black-centered ballroom culture for decades. House music finds its origins in Black safe spaces where we escaped prejudice. And let's not talk about the content creators who adopt our style and mannerisms to build their platform.

It may be time to gatekeep some things.

Karamo's experience represents the story of many Black folks, queer or otherwise, in America. We can be treated with disdain, condescended to without recompense, or, even worse, seen as disposable when convenient. Black women have seen the highest unemployment rates since February of last year, reaching upwards of 7.8 percent, as the public and private sectors rolled back DEI initiatives. Kamala Harris, our very capable first Black, Asian-American female vice president, lost to a man whose links to Project 2025 and increasingly dictatorial language were glossed over. And though pundits argued for days, weeks, and months over the exit results, others firmly believed that the country didn't want a (Black) female president. A notion most recently reiterated by Michelle Obama.

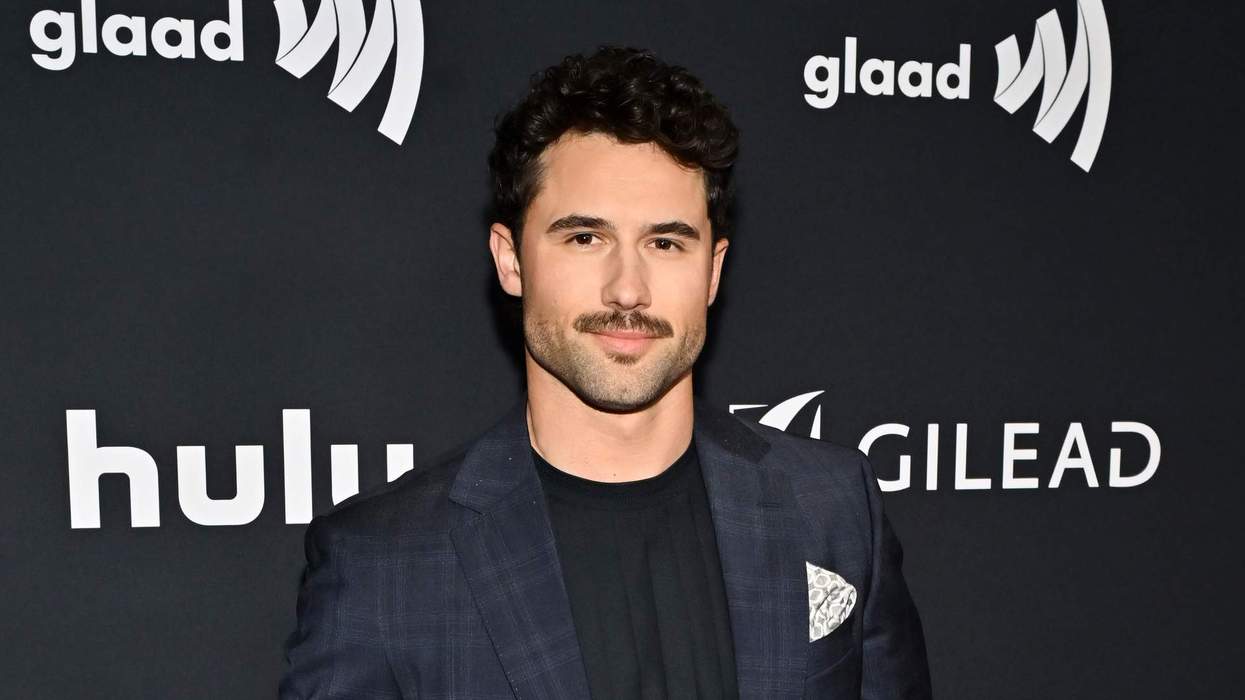

Similarly, we witnessed Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett's electability challenged on a non-political podcast of all places. In a recent episode of Las Culturistas, hosted by Matt Rogers and Bowen Yang. Matt insisted that Crockett's chances of winning a Texas Senate seat were slim, telling listeners, "Don't waste your money." He then says she's a politician who is "well-defined already," whatever that means, and mentions his interest in Texas State Representative James Talarico as a possible candidate, despite knowing nothing about him.

The greatest irony of all? Matt and many other white cis gay men wouldn't be so comfortable in the spaces and places they snide and socialize in if it weren't for "well-defined" Black women, queer, and trans folks. Bayard Rustin, Marsha P. Johnson, Coretta Scott King, and many others stood at the intersection of intersectionality. They placed their bodies on the line in the name of justice and equality, fighting and picketing for all regardless of how one looked, how one loved, or how one prayed.

Still, Black bodies are, at times, tolerated in certain spaces up to a certain point.

What makes moments like Karamo's so unsettling for people to witness is not that they are unfamiliar, but that they briefly pull back the curtain. These moments disrupt the fantasy that proximity to whiteness, fame, or respectability offers protection. If you have enough accomplishments, are visible or agreeable enough, you might be spared from aggression, ridicule, or exclusion. But that's not always the case.

There is a cost to constantly translating ourselves to prove our worth, especially in rooms that were never built with us in mind. That cost shows up in our bodies, mental health, career changes (voluntarily or otherwise), and our joy. Despite this, Black queer and trans people continue to generate culture, language, and movements that the world consumes freely while dismissing our pain and resisting our leadership. That is, until input is needed in the name of inclusivity.

I'm not mad at Karamo for choosing his mental health first. Hell, looking back at previous jobs, I wish I'd done the same. We need to protect and be discerning with our labor, insight, and vulnerability. And to stop auditioning for spaces that demand our shrinkage, if not our erasure, as the price of entry.

Progress does not come from palatability. It comes from our refusal. For the people told they’re too loud, too much, too different, or too "well-defined": keep doing the damn thing. Black joy is grounded in liberation, and liberation is never going to be handed down politely.

And if that makes people uncomfortable, then perhaps that discomfort is the point.

Marie-Adélina de la Ferriere is the Community Editor for equlpride, the publisher of Out.

Opinion is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Opinion stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.