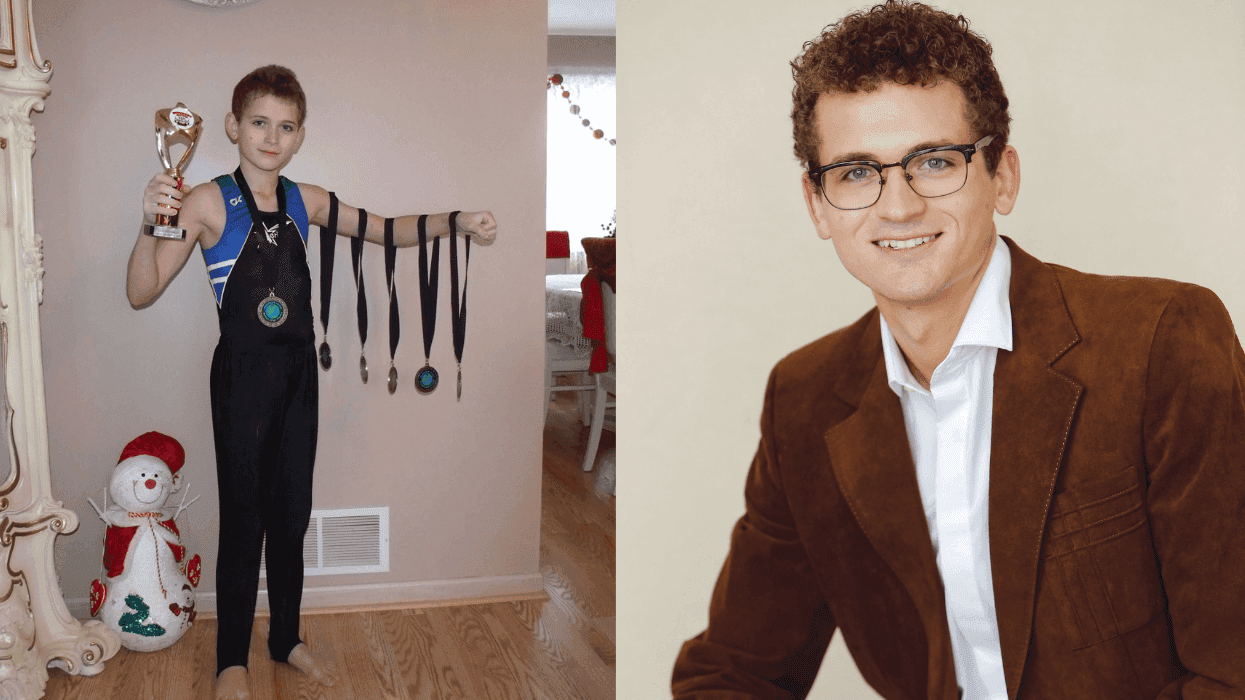

When I was a kid, I did gymnastics, and I loved it. What I didn't love was the moment kids at school found out and decided it meant I "didn't have balls" because I could do the splits.

Fourth grade was basically the year I learned two things: I could fold myself like a pretzel, and apparently, that made me gay.

It's funny in hindsight, but the damage wasn't. Being called gay in a derogatory way at nine years old landed like a grenade every time. By the time I started figuring out my sexuality in high school, the word already felt radioactive. Even now, at 26, if my husband jokingly calls me gay, I still feel a slight and sad twist inside. The bullying didn't just sting — it rewired me.

That era left me with a constant feeling that I wasn't enough. I had almost no friends, especially guy friends. I was the teacher's pet. Partly because no one else liked me; partly because getting perfect grades was the only thing that made me feel safe. I was a perfectionist even before the bullying, but the bullying supercharged it. If I couldn't be liked, I could at least be impressive. I could at least be undeniable.

Somewhere in that fog of split jokes and slurs, I turned 10 and decided I wanted to become a doctor. Not just because I wanted to help people. Don't get me wrong, I love science and medicine, and I can't wait to actually start making a difference. But "doctor" also sounded prestigious. Smart. Important. Untouchable. And, at the time, what I needed more than anything was the protection and armor that a respectable career goal could provide.

My whole personality was shaped by the need to impress. I didn't just want achievements. I needed them. Everything became a performance. Every A+, every gold star, every time a teacher said I was "advanced," it was proof that maybe those kids were wrong about me. By the time I got to college, I saw it as a chance to reinvent myself. Still closeted, but with a clean slate. And that's where I accidentally created the monster — or, depending on who you ask, the icon — known as "the unfiltered guy."

I quickly learned that if I said things others only thought but would never dare to say out loud, people laughed. They liked me. They wanted me around. Suddenly, I wasn't the quiet bullied kid. I was the bold one, the funny one, the one who made shock value look like a personality trait.

And because sexuality was the core wound in my childhood, of course, my sense of humor became sexual. Sexual jokes, sexual comments, sexual facts. If it involved the body, I said it. Not in a creepy way, but in a "why are we pretending sex is taboo when everyone is doing it" way. I lived for the chaos of saying something in a friend group that made everyone scream with laughter. That was the first time in my life I ever felt like I mattered.

And it worked…too well.

I stayed the unfiltered guy through four years of college, two years of a Master's, and two years of medical school. I came out, escaped Catholic guilt, and finally felt like myself. Or, at least, the version of myself I had learned to perform. Turns out, I wore the armor for so long that I mistook it for skin.

Then, this year, someone actually called me out for something I said.

It happened in the break room at work. I had just transitioned into my PhD and started working full-time in a biomedical research lab. My colleagues and I were having lunch when someone brought up prostate cancer. I turned to the guy next to me. I said in a casual but slightly joking way, "You know, you can reduce your risk of getting prostate cancer if you masturbate at least 21 times a month." (Don't believe me? Just ask Harvard.)

Before he could even react, the student across from us said, "Oh…no, you can't say that at work."

Unfortunately, I knew she was being totally serious. "Why not?" I replied. "It's sexual health. It's medicine."

"No," she repeated, like she was the queen of workplace norms. Later, a colleague told me it could've turned into an HR issue if the wrong person had overheard.

I was pissed. I'm still pissed. It felt like censorship — but worse, it felt like the closet. It hit a part of me I thought I'd buried, the part terrified to be seen as "too gay," "too sexual," "too much." The part that learned having a flexible groin apparently meant my whole identity was a problem.

That one comment cracked something open. For the first time, I wondered: Is my unfiltered personality actually me, or is it just the most seamless mask I've ever worn?

Because if I'm honest, every version of me — perfectionist, overachiever, unfiltered comedian — has been built around the same desperate foundation. I want people to like me. I want to feel chosen. I want to prove I am enough.

And that realization hit me harder than any slur ever did.

I looked around at my life and noticed that, despite being surrounded by classmates, colleagues, acquaintances, and party people, I didn't actually have a friend group I fit naturally into. Part of that is on me because I don't always reach out to people first. But no one reaches out to me either. And getting flaked on over and over by someone I really liked made me retreat. Even as an outgoing person, the fear of rejection still hits harder than I want to admit. I have school friends, but it's hard to move beyond surface-level when schedules are chaotic, and I'm assuming the worst before anyone actually does anything wrong.

My husband is my partner and my person, and I'm so grateful for him. But even with all the love we have, we're different people with different communication styles, interests, and ways of moving through the world. Those are things I need from friends. Our marriage doesn't replace the feeling of being understood by others. It doesn't replace belonging.

It made me wonder: If everything from my achievements to my jokes to my Instagram posts were crafted to earn approval, then who the hell am I when I'm not performing?

And what would it mean to stop?

The truth is that the funny, sexual, unfiltered persona saved me. He let me breathe when the closet suffocated me. He made me feel powerful when my childhood made me feel fragile. He taught me that I could be wanted. But he also kept me from being fully known. When your whole personality is shock value, people laugh, but they don't look deeper.

And that's what I'm learning to do now.

I'm not trying to "fix" the unfiltered part of me. I like him. He's fun. He's charismatic. He brings people joy. But I'm finally starting to ask myself whether I still need to rely on him, instead of showing people the quiet, thoughtful, insecure parts that also make me human.

I'm realizing the goal isn't to become less bold or less honest. It's to become truthful about myself, and not just about sex. Honesty as identity, not armor.

I don't have a perfect conclusion to tie this all together. I don't have a five-step plan for self-acceptance. What I have is the first real moment in my life where I'm trying to figure out who I am without performing.

That may be enough.

The bullied kid who could do the splits built a life out of trying to prove he was worth liking. The grown man with the unfiltered mouth added more layers to the same performance. Somewhere underneath both of them is the real me.

I'm finally trying to meet him.

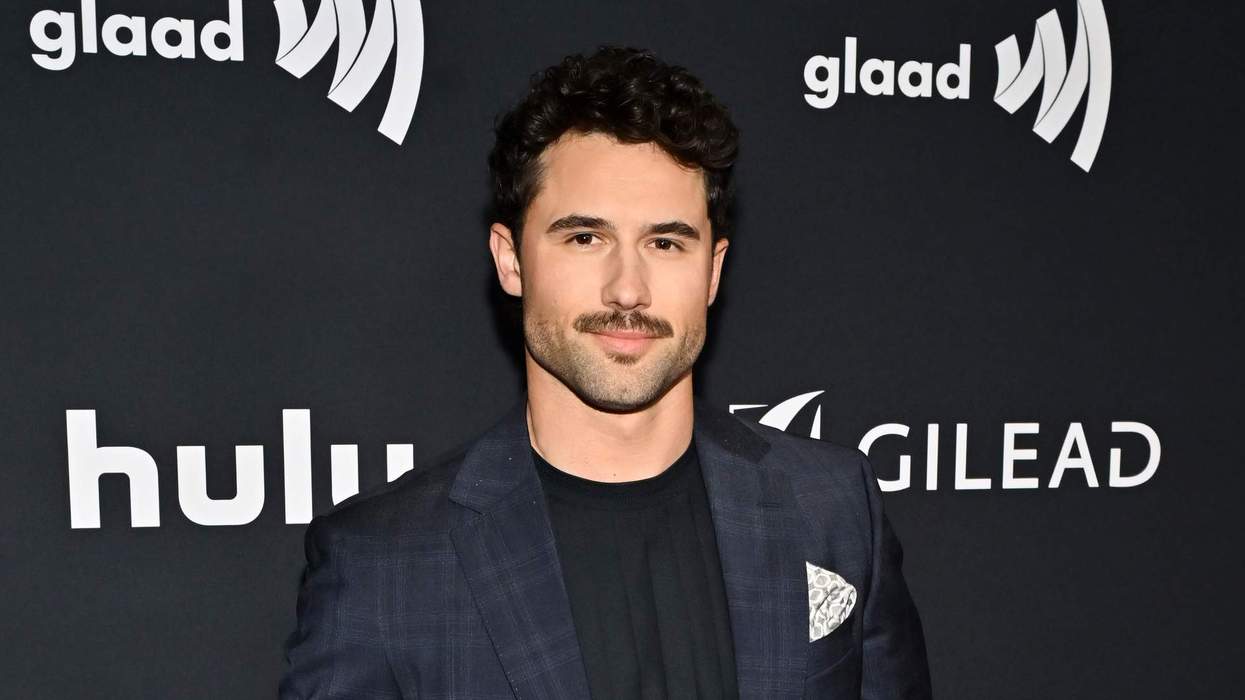

Jack Bruno is a 26-year-old cisgender gay man living in the Greater Houston Area with his husband, Robert, and their golden retriever, Rory.

Opinion is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Opinion stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.