In a ruling that reasserts broad judicial deference to the U.S. military and delivers a major setback to HIV and LGBTQ+ advocates, a federal appeals court on Wednesday reinstated the Pentagon’s long-standing ban on people living with HIV enlisting in the armed forces, undoing a lower-court decision that had briefly opened the door to qualified recruits with undetectable viral loads.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in Richmond, Virginia, reversed a 2024 district court ruling that had declared the ban unconstitutional and out of step with modern medicine. The decision returns force to a categorical exclusion that advocates have spent years trying to dismantle, and it does so by leaning heavily on one of the judiciary’s most durable habits: deference to the military.

Related: Military ban on HIV-positive enlistees could set dangerous precedent, experts warn

Related: Appeals court mulls upholding ruling that struck down Pentagon’s HIV enlistment ban

The three-judge panel was composed of Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, a George H.W. Bush appointee, and Judges Julius N. Richardson and Allison Jones Rushing, both appointed by President Donald Trump. Niemeyer wrote the opinion, which Richardson and Rushing joined in full.

The case was brought by three people living with HIV, Isaiah Wilkins, Carol Coe, and Natalie Noe, along with Minority Veterans of America, a nonprofit that supports service members from marginalized communities. All three plaintiffs have undetectable viral loads, maintained through daily antiretroviral medication. In clinical terms, that detail is decisive: people with sustained undetectable viral loads do not transmit HIV and can live long, healthy lives. The science on this point is not controversial. It is, in public health terms, settled.

But the court did not treat the case as a referendum on science.

Niemeyer described the dispute as one about institutional roles and constitutional boundaries. The Constitution, he emphasized, assigns Congress and the president, not the courts, primary authority over the composition and regulation of the armed forces. And when judges review military policy, even policies that touch constitutional rights, they do so through a lens clouded by deference.

Under that lens, the HIV enlistment ban survives.

Related: Court strikes down last barrier to military service by people living with HIV

Related: Let People Living With HIV Enter Armed Forces, Lambda Legal Tells Court

The Department of Defense and the Army argued that even well-managed HIV creates operational complications: service members must have uninterrupted access to daily medication, require regular lab monitoring, and cannot participate in the military’s “walking blood bank” system—an emergency practice in combat zones in which soldiers donate blood directly to one another. The government also cited higher long-term medical costs and diplomatic complications in countries that restrict the presence of people living with HIV.

Any one of those rationales, the court said, would be enough under the forgiving “rational basis” standard of review, especially in a military context, where courts grant “great deference” to professional judgments about readiness and deployment. Together, the panel concluded, they more than suffice.

The ruling wipes away a major victory for the plaintiffs in August 2024, when a federal judge in Virginia found the policy “irrational, arbitrary, and capricious” and barred the government from enforcing the HIV-specific enlistment rules. That decision had also ordered the Army to reconsider Wilkins’ removal from a military preparatory program. For more than a year, until the Fourth Circuit stayed the injunction last December, the military accepted qualified recruits with well-managed HIV. Advocates say that the experiment proved the policy’s underlying assumptions wrong.

“From August 2024 until that stay took effect, the military successfully accepted qualified individuals with well-managed HIV, proving that people living with HIV can serve effectively alongside their fellow service members,” Lambda Legal said in a statement after Wednesday’s ruling. “Today’s decision disregards real-world evidence and returns to outdated policies rooted in stigma rather than science.”

Related: Two military members denied promotions for having HIV just won their lawsuit

Lambda Legal, which represents the plaintiffs, condemned the decision in stark terms. “We are deeply disappointed that the Fourth Circuit has chosen to uphold discrimination over medical reality,” said Gregory Nevins, the organization’s senior counsel and employment fairness project director. “Modern science has unequivocally shown that HIV is a chronic, treatable condition. People with undetectable viral loads can deploy anywhere, perform all duties without limitation, and pose no transmission risk to others. This ruling ignores decades of medical advancement and the proven ability of people living with HIV to serve with distinction.”

Scott Schoettes, who argued the case on appeal, said the court’s reliance on deference had been stretched too far. “As both the Fourth Circuit and the district court previously held, deference to the military does not extend to irrational decision-making,” he said. “Today, servicemembers living with HIV are performing all kinds of roles in the military and are fully deployable into combat. Denying others the opportunity to join their ranks is just as irrational as the military’s former refusal to deploy servicemembers living with HIV.”

Advocates had hoped the court would follow the logic of earlier cases that forced the military to abandon blanket restrictions on service members who acquire HIV while already in uniform. In those cases, judges recognized that modern treatment had transformed HIV from a fatal diagnosis into a manageable chronic condition and that policies built on older fears no longer made sense.

Related: Federal appeals court upholds block on Trump's trans military ban

The Fourth Circuit distinguished those precedents. In those cases, the panel noted, people were already serving, sometimes with access to individualized waivers. This case, by contrast, concerns the front door: who gets to try to serve at all. The military, the court said, is entitled to draw harder lines there.

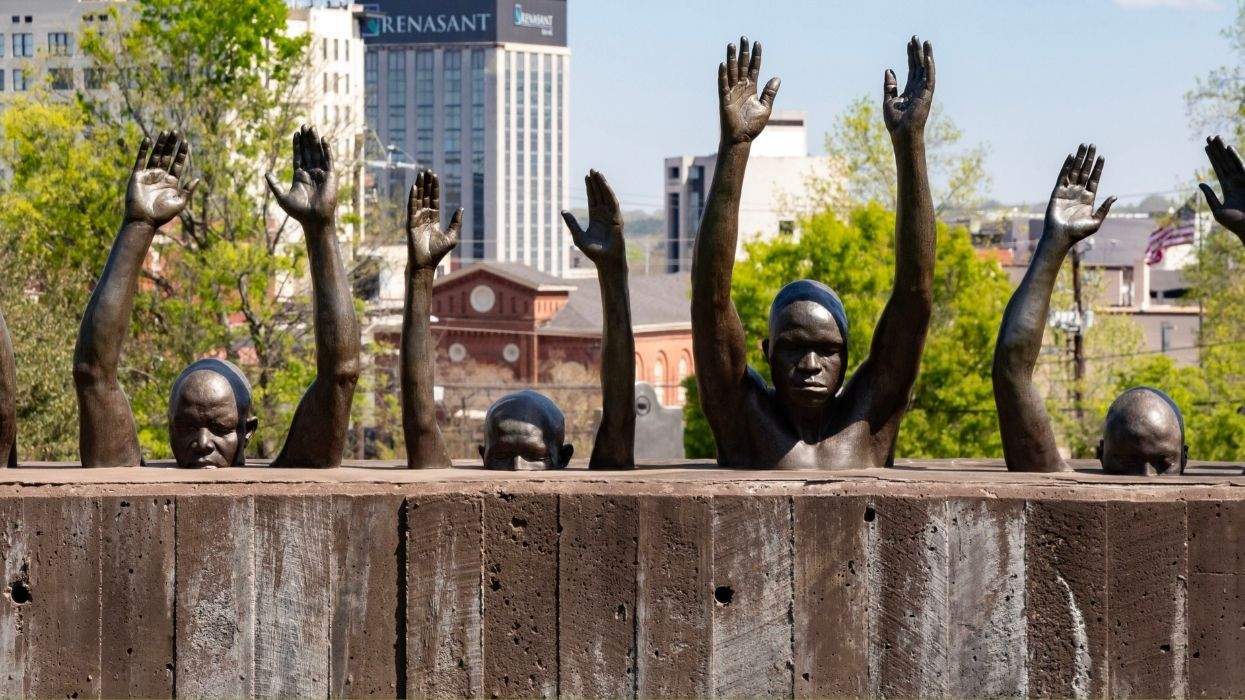

The result is a legal posture that many advocates see as disconnected from life outside the courthouse. In civilian society, people living with HIV serve as doctors, teachers, and first responders. In public health, “U=U”—undetectable equals untransmittable—has become a cornerstone of education. In federal court, however, HIV remains a legally sufficient reason for categorical exclusion, so long as the institution doing the excluding is the U.S. military and the judiciary is willing to defer.

What happens next is uncertain. The plaintiffs could seek rehearing before the full Fourth Circuit or ask the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case.