Memory is a tricky thing.

My friend Felix Gonzalez-Torres once said, "Each of us perceives things according to who and how we are at particular junctures, whose terms are always shifting."

So I think, OK, I've had a great life with memories culled from a long list of fantastic, seemingly improbable, some say phantasmagorical experiences and friendships. But for me, it's as though these things happened to someone else, and I only realized how important they were after the fact. I'm not sure if it was naïveté, or my terminally blasé nature, or my Teflon indifference, as one exasperated therapist called it.

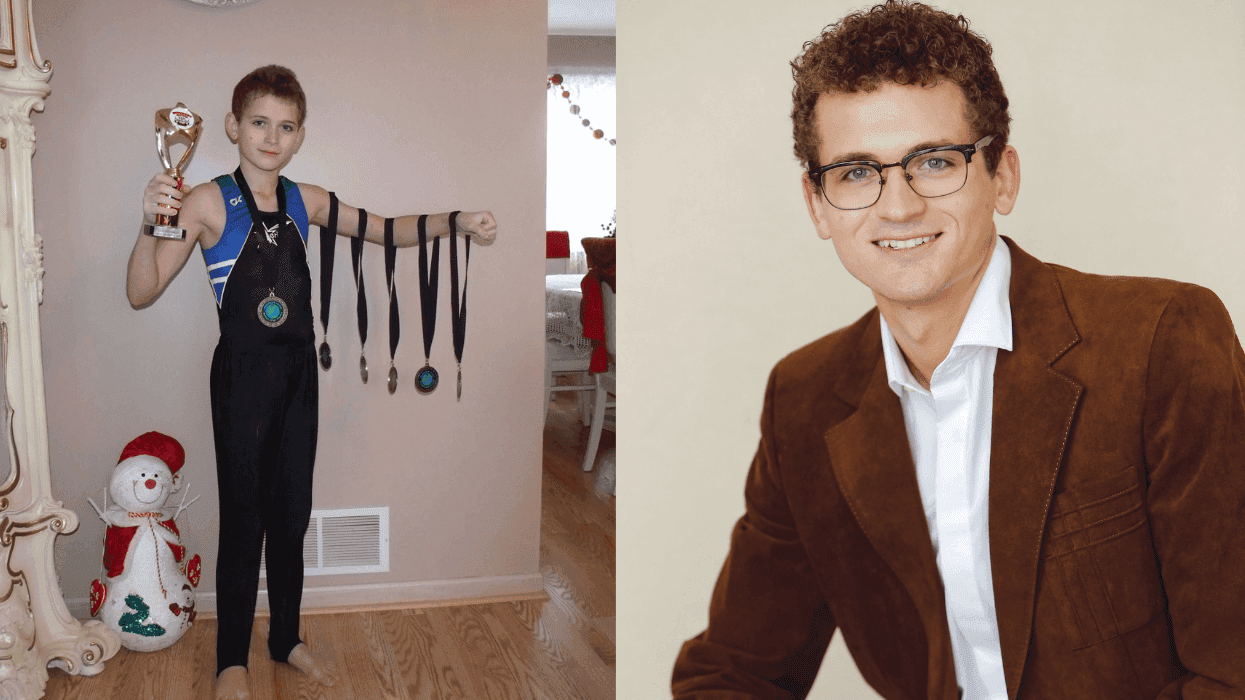

One of the few memories that has always felt very real to me dates to my childhood in Canada, when, on cold winter days, with snow drifts like white, ominous mountains enveloping that place I called home, I’d rush from school, lace up my skates, and trudge across the snow drifts, down to the river's edge. Alone, I would skate for miles in the early evening silence, just the schoosh schoosh of the blades on the rock hard ice, the witchy blackness of the early night, and my plumed breath in regular procession.

It is this memory that conjures up Ross Laycock, my indomitable gay brother, the prankster, the exuberant athlete and opera buff, the very embodiment of a certain kind of Canadian sprezzatura. Ross, who like so many, was murdered by Ronald Reagan’s toxic black hair dye and Nancy Reagan’s blood-stained Adolfo dress. By Jesse Helms’s southern-fried homophobia, and New York Mayor Ed Koch’s slammed-shut and padlocked closet door. I’m remembering Ross today, who died of AIDS-related illnesses, 35 years ago on January 24, 1991.

I met Ross in 1978 while we were students at McGill University — he a science major, and me, art history. Then, in the spring of 1980, Ross moved to New York to study menswear design at the Fashion Institute of Technology but soon realized he was not a fit for FIT — that he’d rather buy clothes than design them. I arrived six months later in November. As different as two young gay men could be, I felt deeply bonded to Ross because he represented a kind of unfettered freedom I had never known or understood, and for him, I was the brother he never had.

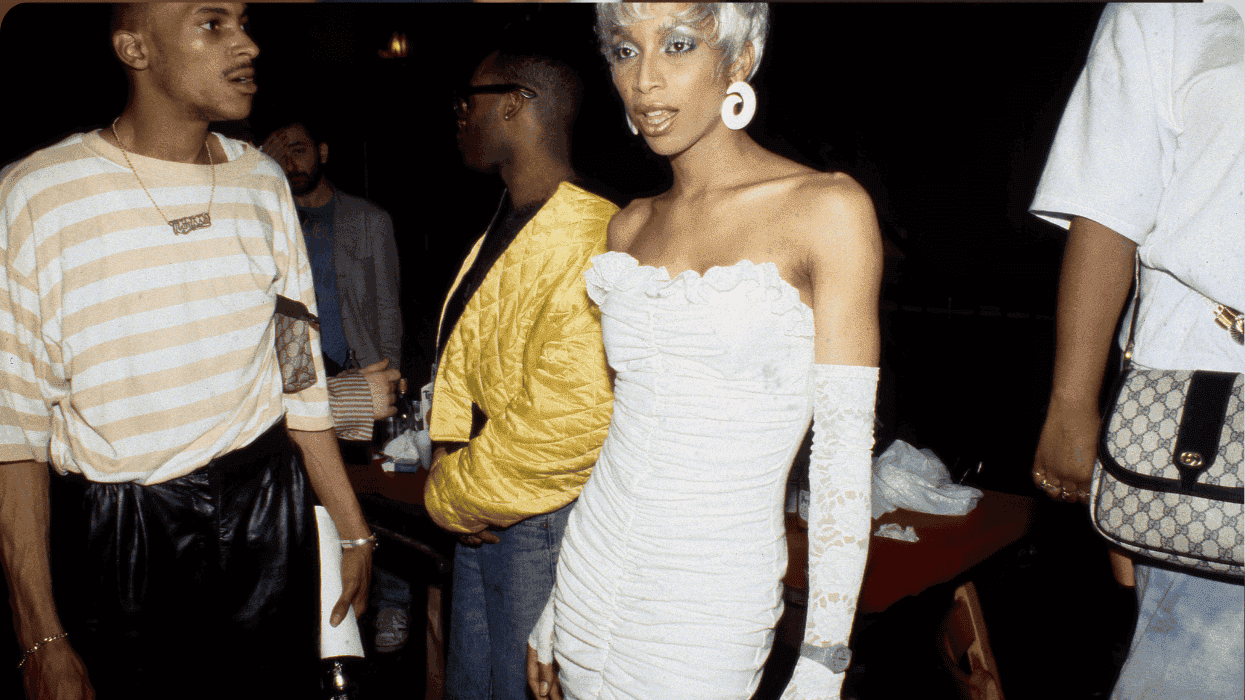

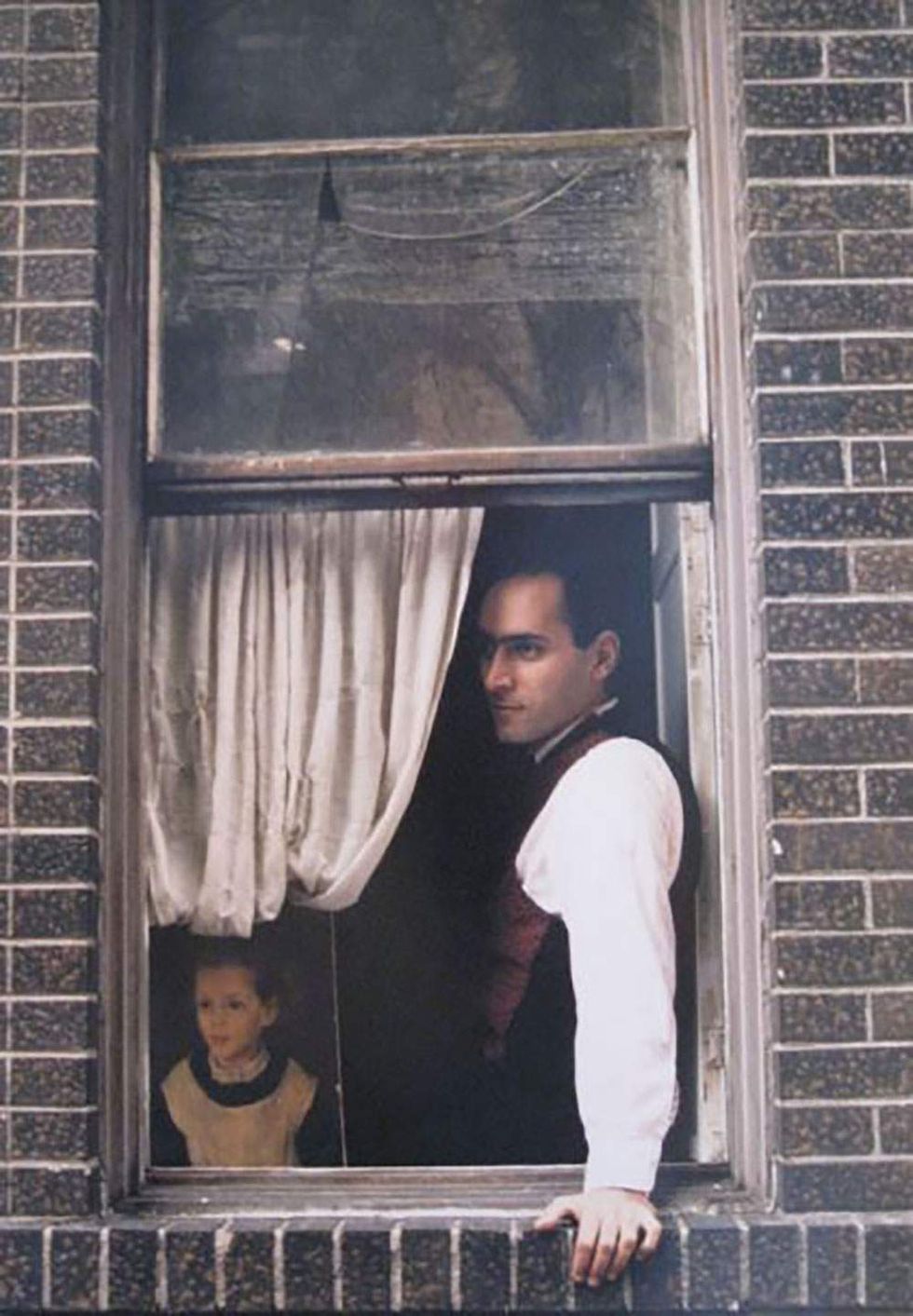

The first time I saw Ross and Felix together was at a cocktail party in Manhattan in 1983. The two had met a few weeks prior and were already madly in love. It was obvious that Ross had finally found in Felix his ideal man, and Felix had found his “audience of one." I gave my approval.

Their intense relationship played itself out within the context of Reagan’s America, a time of great difficulty for many people, in particular gay men and lesbians. For some of us, it was also a time of great creativity and profound personal change, of art-making and vibrant activism centered on a spiraling “government-sponsored holocaust” as art critic Darren Jones named it. We opened our hearts and minds and grew in ways we never knew possible, but the tsunami of AIDS came roaring in and threatened to drown us.

Ross came from a family of girls — three sisters, where they all grew up in Inuvik, the Northwest Territories of Canada, in a small village called Norman Wells. I believe there is a kind of spectacular and unique beauty to that place, as he described it, but also boredom and tedium for a young boy. His father died when he was nine, and I know that affected him deeply. His mother, with few options, sent him to what is known in Canada as a "residential school," an awful place, funded by the Canadian government, which forced Indigenous children to not speak their native languages, give up rituals and traditions including clothing, food, hunting, and adornments, and be indoctrinated into the Catholic liturgy. They used torture, starvation, psychological manipulation, and even murder to bend these children to the white man’s way. “Ross, as the only non-Indigenous student at the school, was bullied and abused by other students. I think his confidence, resilience, and charm helped him survive,” his sister Janice remembered. That is the adult Ross that I knew, and the Ross that Felix fell in love with, who he described as “strong as a horse; he could build anything.”

They were in so many ways the most unlikely/likely pair. Felix had been born and raised in Guaimaro, Cuba — the birthplace of the Cuban independence movement, and was separated from his parents in their decision to get him and his siblings out of Cuba as Castro swept into power. This left him feeling unmoored and alone until he eventually landed in New York City where he found a sense of home, something most important to both of them, and which they found in each other.

Ross eventually left New York and returned to Canada to continue his studies in biochemistry at the University of Toronto. He and Felix continued their love affair traveling between New York and Toronto, to Paris, Italy, and spending months in Los Angeles while Felix taught a semester at CalArts. They would spend every summer traveling the northland of Ontario, sleeping in a VW minivan, cooking over an open fire, hiking, swimming, and watching beavers build their dams, while Harry, Ross’s black Labrador, chased squirrels.

Ross became involved with the activist group AIDS Action Now!, and in 1989, organized direct actions at the fifth International AIDS Conference in Montreal, cowriting a manifesto of demands activists issued to the government of Canada as they stormed the stage at the opening plenary session.

I think of Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous phrase: "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." And it gives me hope. I appreciate the hard-won gains we in the LBGTQ+ community have made in the last 40 years, which were built upon the foundations laid by our brothers and sisters in the 60 years prior. And young people, who are smart and savvy, and seem to have a broad sense of acceptance and love for each other, without judgment, is the very definition of progress. Still, there is more to do.

Thing is, the arc of justice sometimes snaps back, and we find ourselves, once again, facing ugly prejudice, extreme threats of violence, and seemingly impossible odds. Now, hateful anti-trans legislation is being passed in many states, and misogynistic rhetoric spews daily from the Oval Office. We see the current administration canceling World AIDS Day and threatening the highly effective PEPFAR global health initiative, which provided life-saving care to people in developing nations around the world.

We also see pernicious attempts to erase our very existence, and our love, like at recent exhibitions of Felix’s work at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York, the Chicago Art Institute, and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, where Ross’s name was very intentionally either marginalized, or completely erased from gallery and museum labels and catalogues, along with words like gay, Latino, Cuban, HIV, and AIDS in biographical information about Felix — who was, in fact, all of those things and more.

I know a few things from my years as an artist and activist. Organizing and direct action works, community building works and nonviolent protest works. But mostly I know, even with these setbacks, we will survive.

The last time I saw my friends Ross and Felix together was as a huge pile of candy on a museum floor in New York City. The installation, Untitled (“Lover Boys”) 1991, had an ideal weight of 355 pounds of thousands of shimmering, silver, foil-wrapped candies, and was equal to the weight of the two men combined. Visitors to this installation, which Felix created for the Whitney Museum's 1991 Biennial Exhibition, were invited to take pieces of the candy, and as they did, the pile slowly dwindled — a metaphor for the gradual dissipation of two lives. It forged a charged connection between public dissemination and private ownership, popular discourse and rarified art theory, between the daily lives of gay Americans and the right-wing maelstrom sweeping the nation in the epidemic's early years.

I remember that glorious summer day on Jones Beach when I took the photo of Felix and Ross, bursting with love for each other, looking sexy and glamorous, not a care in the world. But it was not to be. Just a few years later, I gave Ross his last bath, his skeletal body covered with Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions. And soon thereafter, my friend Sharron Campeau and I made funeral arrangements to his exacting specifications; that his ashes be separated into 100 small bags so Felix could carry him everywhere and leave a bit of Ross in the places they both loved.

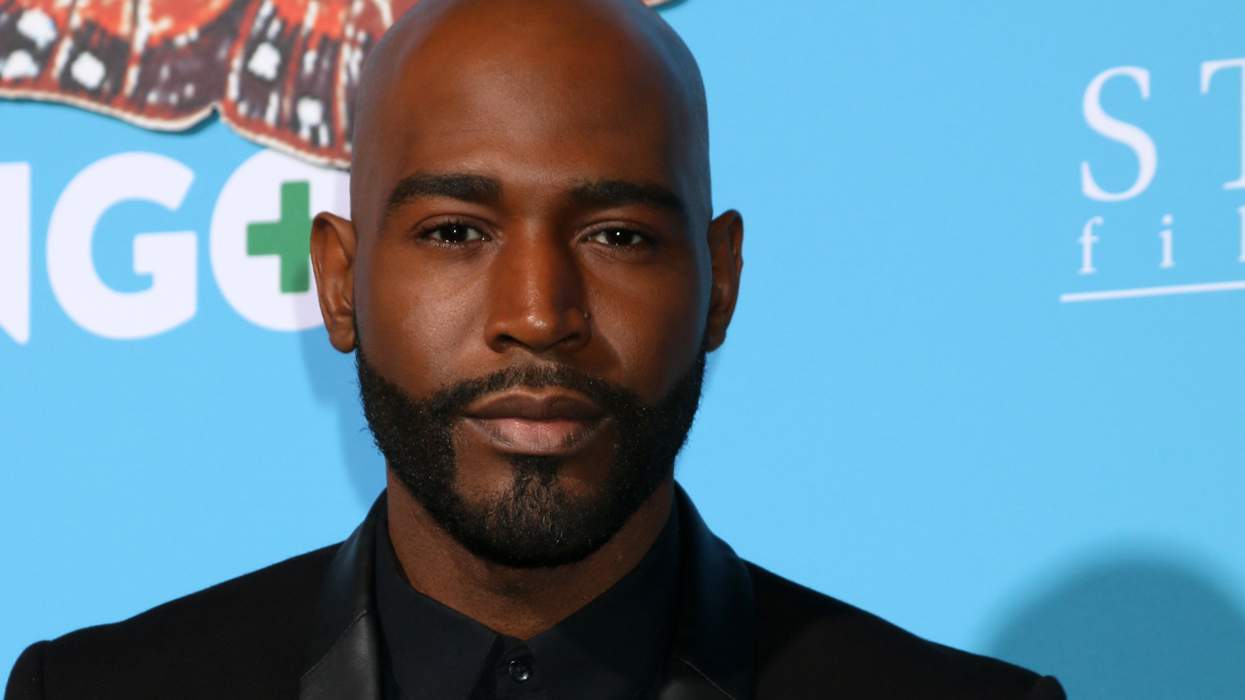

Carl George is an experimental filmmaker and curator who has presented screenings and exhibitions in art venues and museums internationally. His films are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, the Guggenheim, and the New York Public Library. George is the recipient of many grants and honors, including the Canada Council for the Arts, the New York State Council for the Arts, and the Getty Research Institute where his archive of personal correspondence resides.

Learn more at carlmgeorge.com. Find him on Instagram @carlmgeorge.

Opinion is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Opinion stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.