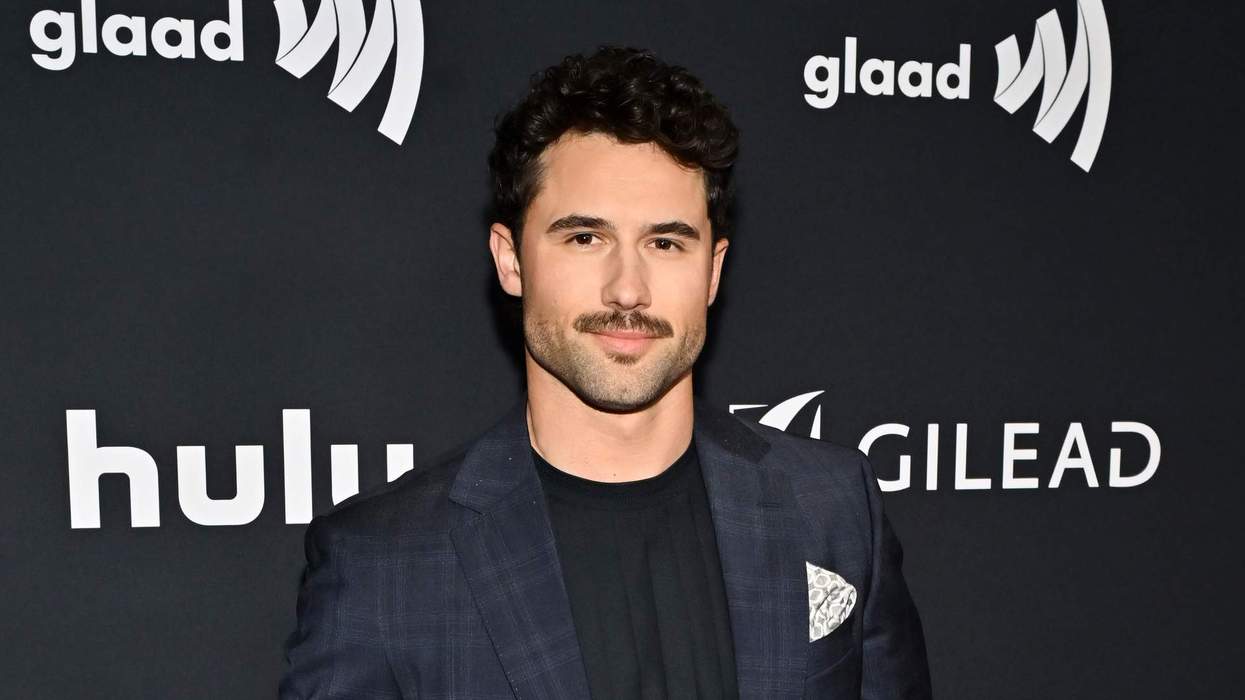

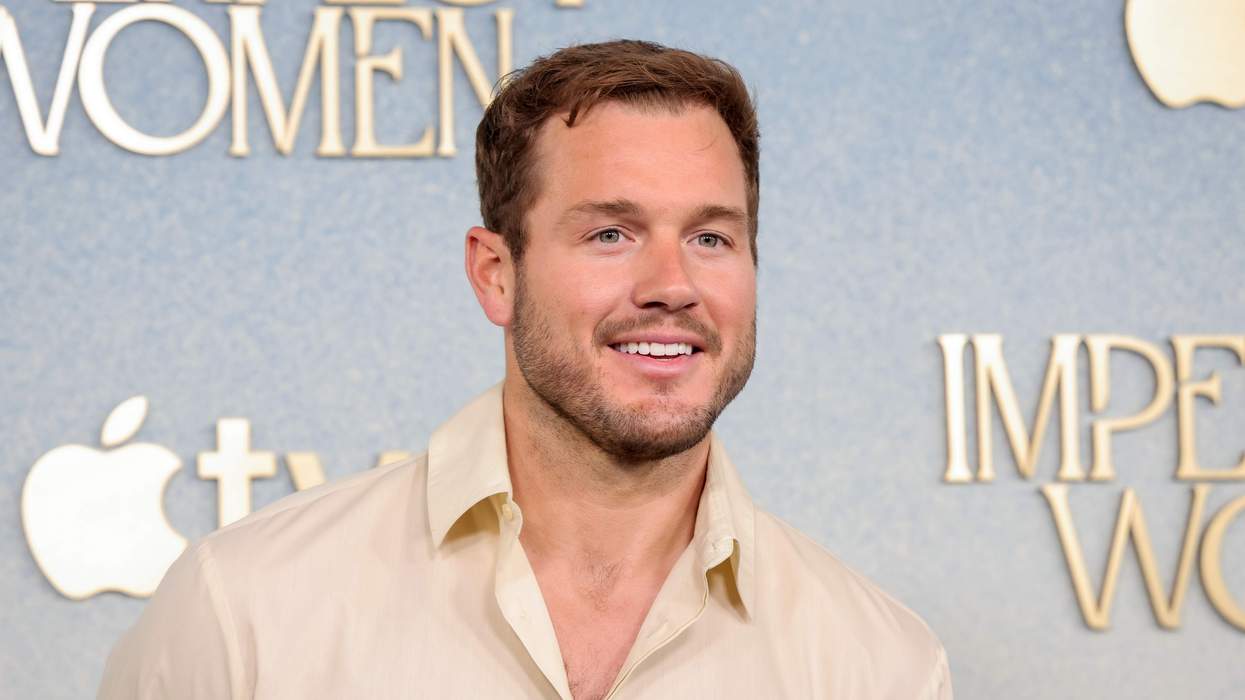

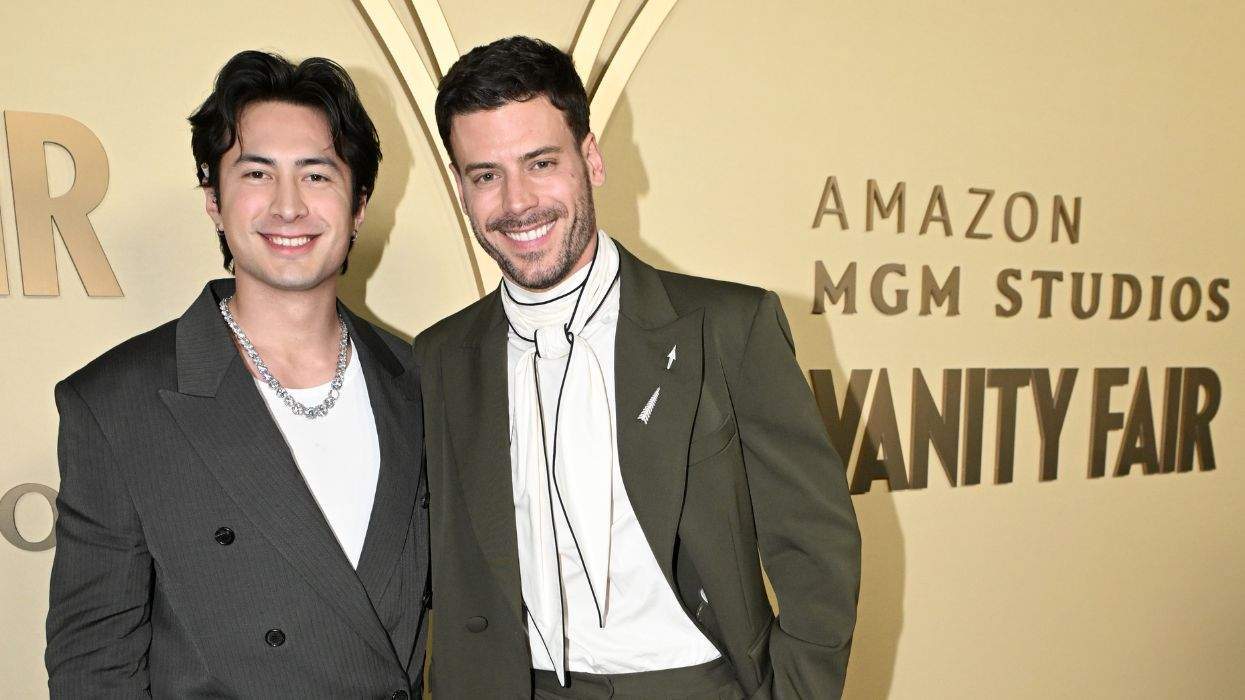

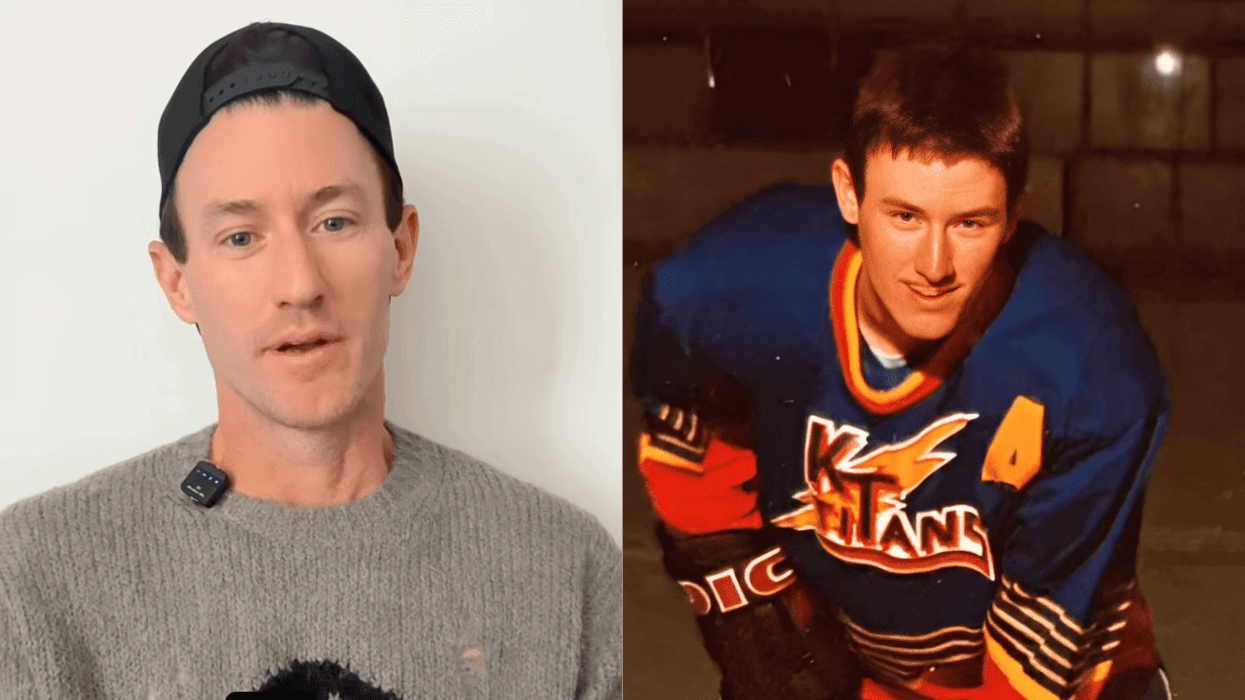

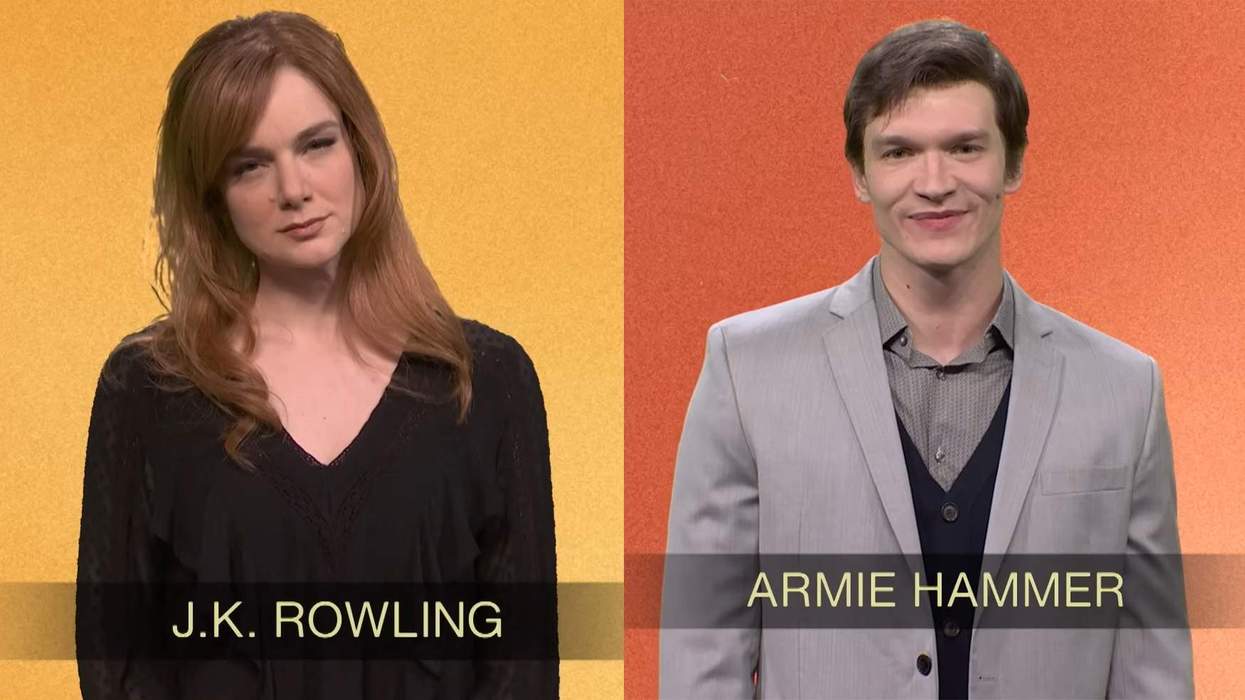

Heated Rivalry episode 4 introduced fans to Connors, another pro hockey player who rooms with fellow teammate Ilya Rozanov (Connor Storrie) and is played by Harrison Browne. After dedicating his entire life to hockey, coming out as a trans man, and starting an acting career, Browne still struggled to land roles on hockey-themed movies and TV shows. However, let's just say that 2025 was a game changer (pun intended) for Browne, who went on to write, direct, and star in his own short film, Pink Light, and had his talents recognized by showrunner Jacob Tierney, who secured him a role on the hit TV show from Crave and HBO Max.

Browne was an actual professional hockey player from 2015 to 2018 in the Premier Hockey Federation (formerly known as the National Women's Hockey League). Upon coming out to the public, Browne he became the "first openly transgender athlete in professional team sports in North America," which encapsulated every single sport (not just hockey), as reported by The New York Times.

In 2025, Browne published a non-fiction book with his sister, Rachel Browne, titled Let Us Play: Winning the Battle for Gender Diverse Athletes. He wrote, directed, and starred in his first-ever short film, Pink Light, which premiered at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. Now, he is reaching an even bigger audience as a Heated Rivalry star.

Over the course of our conversation, Browne tells Out how he navigated each step within his coming-out story as a trans athlete, discusses his new short film Pink Light, recalls his casting process on Heated Rivalry, and teases a very exciting project currently in the works.

Out: Many people were recently introduced to you through Heated Rivalry. How would you explain your coming-out story as a trans man who still competed as a pro hockey player after disclosing that information?

Harrison Browne: I came out as the first out transgender athlete in professional team sports, That's the title that I would say it is. I played in the NWHL, which is now known as the PWHL, and I came out through an ESPN article in 2016.

However, since I was playing women's hockey, I was beholden to anti-doping protocols. So, at first, all I could do was to come out socially. I was really embraced by the league at that time. Hockey is my entire life, so it was really nice to just be able to be myself while playing the sport.

When did you start playing hockey?

I actually started at nine, which is kind of late for a Canadian. I was a soccer player, but one of my best friends growing up, her dad was in the NHL, and I wanted to do everything that she was doing. So I tried it, and I just fell in love with the speed element of it and like being in a different environment, being in this cold rink and being able to just skate faster than I could run. It was just this whole other world that I could be part of. I loved it.

You retired from professional hockey and started an acting career, which subsequently included honing in your skills as a writer and director. Your short film, Pink Light, is amazing — and you're now on Heated Rivalry, one of the biggest shows of 2025. What was it like, to pivot that way?

Yeah, it's not really the typical route that you see a lot of hockey players go to, right? [Laughs.] But I think it had a lot to do with my story and the media attention that I did receive.

I was in some documentaries and had cameras following me around for about two years. I was also asked to do a lot of public speaking events. I was memorizing lines and doing all these things, but I had to retire because I wanted to physically transition. I couldn't live my life in this limbo anymore.

However, when I did retire, I didn't know what to do with my life. I was losing my identity as an athlete who had played hockey for 16 years, day in and day out. Suddenly, I just had all of this free time. Nobody telling me what to do, which diet to follow, or even where to be. I was really stuck in figuring out what I wanted to do with my life.

And then Scarlett Johansson almost played a trans man.

Oh!

When that happened, I saw an opportunity for a trans story to be told, but it got squashed. I didn't know any trans man, especially one who was an actor. Elliot Page hadn't come out at that time. I saw this gap in the market, I knew I was comfortable in front of the camera, and I knew I'm comfortable memorizing lines. So I just started to take acting classes.

I didn't think I was going to be Scarlett Johansson-level of acting right off the bat, but I know what training is. I know what it takes to learn a skill and commit to something. So I just dove in and didn't look back. It's pretty crazy to think that that little decision, and Scarlett Johansson, were these little sparks that shot it off.

That controversy happened around "the tipping point" — which was really epitomized, I think, with Laverne Cox on Time magazine. We had many exciting and queer-inclusive shows like Orange Is the New Black, and Pose, and the excellent documentary Disclosure also came out around that time on Netflix. Going into showbiz, did you know that it was — unfortunately — going to be an even bigger challenge for a trans male actor to get cast and break through?

Growing up, I can point to Boys Don't Cry as the only thing I saw that seemed like it represented a future for me... and that was really bleak. I wanted to challenge the entertainment industry. We need three-dimensional trans representation, and having them in stories that aren't just about transitioning, too. Stories that show an adult who's past that point in their life. There's so much more than just the transition aspect of it. I just really wanted to create that for myself. For somebody, looking in, who needed to see it at a younger age.

RELATED: Trace Lysette's performance in Monica was breathtaking — and absolutely deserved an Oscar

I knew that there wasn't a lot of trans masculine representation; there was a big gap in that. But I didn't see it as a challenge, I saw it as an opportunity, because I saw firsthand how much my representation in sports meant to people who were looking in. I get messages on social media all the time from parents concerned about their child, and even young adults who are still struggling. The messages are usually like, "Seeing you be yourself really helped me."

Athletes have always told me about all of these grateful, and sweet, or intense messages they get from fans. It also seems like this comes from all kinds of senders: Young folks who feel seen, or a kid's parents, or even young adults. Representing the LGBTQ+ community in sports feels even more intense than most other public-facing careers. How do you navigate those messages that, while important, and sweet, can also be pretty heavy, and heartbreaking?

It can be very heavy. Especially after the recent election and what's going on in the States, it's been tough to stay positive and to protect your mental health in that space. I feel a lot of empathy towards kids that are being barred from playing sports, and who are being barred from medical care, and parents that have to deal with this... just so much hate and negative rhetoric that's happening around trans individuals.

What hurts me the most is thinking about kids who won't be able to play sports, because I then think about how much sports meant to me. Sports saved my life. It was a space that I could identify as an athlete. It was a space that I didn't have to "be a woman," or have to identify as a man, or anything like that. It was just a gender-neutral space that I could be free with my friends, and make memories, and build confidence. I don't know where I would be without that.

It's hard for me to hear from young people like, "I don't know what to do," because I felt pretty helpless in some spaces, too. But I always try to respond to as many [messages] as I can, and speak on my own perspective, and just send messages of support and hope. That's all we can really do right now.

Ultimately, I wanted to do something about what's happening in the States: This conversation around trans athletes in particular. So I teamed up with my sister to write a book called Let Us Play: Winning the Battle for Gender Diverse Athletes. It explores things we can tangibly do, like debunk myths, interrogate what's happening in the media, show facts, stats, and really fight for this community. Also, accepting what I can't do in this moment has helped me a lot, because I felt really helpless at times. I didn't know how to fix things, or make things better, for people.

Doing that within my own circle... I found a lot of comfort in that. I know that it's been helpful for youth and parents who have read the book, too.

Many gay athletes have struggled with "locker-room talk" over the years, with the broad understanding of that term is connected to cis straight men boasting about themselves and speaking negatively about women. Was there, perhaps, a different version of that in your league? Did you feel comfortable coming out as a trans man to your teammates?

Women's hockey, in particular, has been such a safe space for me. I can only speak to my own experiences within locker rooms, but have look in on the PWHL right now… Players date each other. Players have short hair. Players really go out of the gender binary, and really fight for themselves to be able to express themselves in the way that they want to be. They don't even need to identify in the LGBTQ+ community — just a strong woman who wants to be muscular and wants to break down these ideas of what masculinity means, or what femininity means.

Within women's hockey locker rooms, I think most people can understand what discrimination is. Most people can understand what it's like to be judged based on who you are, and what you're capable of doing, and being put into boxes means. For me, most of our dressing rooms were like 50 percent gay, 50 percent straight. I didn't know many trans athletes growing up, and I didn't encounter any out transgender individuals while I was playing, but I knew that most people in the league understood the LGBTQ+ community.

And, with hockey, we're all called our last names, or nicknames, anyway. I didn't have to deal with "my birth name that I wasn't really connected with." I could just be Brownie within those spaces, 'cause my last name is Browne, and Brownie was my nickname.

I just told them one day, "Hey, I'm still the same Brownie, but can you use he/him pronouns?" And everybody was like, "Yeah, absolutely." Mistakes occasionally happen because it is a gendered space. So there's a lot of "let's go girls" and "let's go ladies." But that's okay, it happens. You don't want people to walk around on eggshells.

My teammates and coaches in the [formerly named] NWHL always wanted to make sure that I was feeling the most included that I could possibly be. I didn't have many negative experiences through coming out, and I wasn't worried about coming out in that environment.

At this point in time, I think many straight, cis people can understand the concept of queer people having to come out several times, at different points — there are relatives and personal friends, there are peers and colleagues, and eventually you might come out to the public. If you're comfortable discussing it, how did that timeline look for you?

So I came out publicly in 2016, when I was playing the NWHL. But I had come out in college, already, I think either my sophomore or junior year. I was probably 20 years old when I came out to my teammates at that time. I was always known in the women's hockey world as "the trans man playing on the team," it just wasn't public knowledge at that point. But I did come out four years prior to coming out publicly [as a professional athlete].

Over the years, I did have moments of deep fear. Like, "How are people going to accept me for being a man when I don't look like one, or when I don't sound like one?" But I always had the support of at least one or two of my teammates that I could disclose things and could really feel comforted. First comforted by them, and then when coming out on a larger scale.

It wasn't just like, "Here I am!" [Laughs.] It took a while to feel comfortable in my own skin and even accept myself. But yeah, I am very fortunate to have had the reception that I had.

Pink Light is a very cool short film that you wrote, directed, and starred in. The project centers a former pro hockey player who "time travels back to his per-transitioned self, when he was waiting for life to begin" (via Mubi). What inspired you to make Pink Light, and how did the actual short film come about?

It really came from feeling a bit frustrated at the types of trans characters that I was auditioning for, and not feeling like I was getting the opportunities that I wanted to tell a really deep trans story. So I was like, "Well, I gotta create this myself." Then, when it came down to writing it and directing it, I started to really fall in love with that process. The process of directing, in particular, I didn't realize that I would really enjoy.

Acting is really subjective. And that, to me, is sometimes elusive. To be like, "What are we doing in this space?" That amount of control is not there, for the most part. But directing is this space where I actually felt like I was playing hockey. I don't know how to explain it! [Laughs.] But I had this control, and these teammates that I was able to work with, and we all had different roles that we were playing; different things that we had to achieve.

The person who played the younger version of me, CJ Jackson, is this really popular player in the PWHL, and an amazing actor, too. Pink Light was their first time acting. And CJ also related to it feeling a hockey game. I was like, "I know." Both of us had that similar kind of feel.

I've always loved those abstract conclusions, and observations, and conversations that we can have between collaborators in a creative process. And finding common ground is exciting, but I even love to just hear someone trying to make sense of things and explain something that they haven't figured out yet. Feeling vulnerable about something and still wanting to figure it out with other people is magical, but we keep getting fewer chances to do that with one another. I think that's why we need the specificity of things to be explored in a project like Pink Light.

I really wanted to create something that I wish I had seen when I was younger. People don't know what it is like... Dealing with this stuff A lot of people have been talking about trans athletes. And I was like, "You don't understand what being trans, and being an athlete, and having to have these juxtaposing identities, feels like."

I wanted to give a voice to this community that's being talked about ad nauseam right now, and create something that I really needed to see when I was struggling with sticking with my sport and accepting myself.

Hearing you say that reminds me of Elliot Page who also went in the direction of producing, and directing, after finishing his run on The Umbrella Academy. He was clearly very grateful for the show immediately changing things up to honor, and celebrate, and reflect his coming out as trans. But once that wrapped, I think we all identified he had this new curiosity to pursue his own stories.

Yeah, I think there's a really big power in taking back the narrative, and taking back storytelling, for your own community — especially when lots of people have been doing it for us. Why are we letting people tell our stories when we are more than capable of doing it? This has been a really empowering experience for me.

RELATED: There are no out NHL players. Could Heated Rivalry change that?

I'm in the process of developing a feature and we just got funding for a portion of it. It has empowered me to feel, especially as an actor, to not feel like I have to wait for something. It's really been life-changing.

And that feature is the longer version of the Pink Light short, right?

Yes! So we premiered at TIFF in September, which was really amazing. We had a couple of production companies asking, like, "What's next? We want more from this." And most of the audience, even, was like, "We want more. There's 10 minutes; it's too short."

So, yes, the feature is a continuation of it that lives more in the past version. We dig deeper into college hockey, and the NCAA hockey, and being a trans athlete, and figuring out how you navigate those spaces while really celebrating the queer community within women's hockey as well.

Let's talk Heated Rivalry. Given your legacy in professional hockey, and your pursuit of an acting career, did producers approach you to be in it? Did you audition?

I just auditioned. Obviously, being a hockey player, that's one of my niches. Anytime that there's a hockey movie or hockey TV show, I'm usually seen for it. But this is the first time that I've ever landed one. And to play an NHLer — or MHLer, 'cause they renamed the league — has been an amazing experience for me to not feel imposter syndrome.

It's been so interesting for me to feel that way through acting. I think everybody can relate to the physical nature and the optics of what acting is. And so, myself, I'm 5'4". I am not a large person. I'm muscular, I'm fit, and I know how to play hockey, but I don't necessarily read as a hockey player to somebody watching a TV show. They're like, "Oh that guy's too short," or whatever.

I've felt a lot of imposter syndrome, going out for these roles, and the breakdowns are like 6'3", really large, big stature. I'm not that. I really tried to think what the casting directors would want to see out of a male hockey player, and I tried to conform myself to their idea of that character. Heated Rivalry was one of the first times when I just showed up as myself.

There are many short men in the NHL. There's Martin St. Louis. There's Nathan Gerbe, who used to play.

I'm not an authority on hockey, but that stature sounds wild. I mean, this isn't basketball.

Right! And it's even skewing more to smaller players now that there's not as much physicality. So I just took that out of the narrative and decided to just be myself. I have a large breadth of hockey experience that I think can be really good for a television show with this nature.

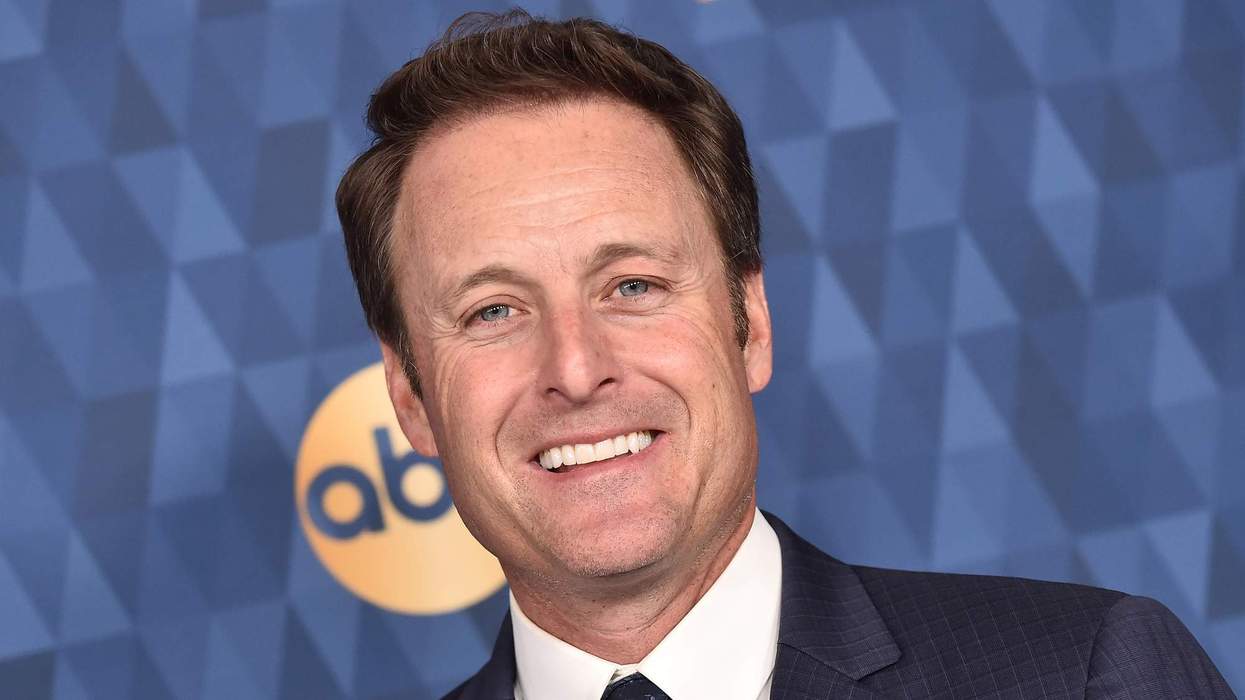

I auditioned for a character, and I didn't land that character. But Jacob Tierney [Heated Rivalry showrunner] reached out to my agents and said, "I want to offer him this other character." I was just like, "Absolutely, that sounds amazing."

To be included in that, and to just hear, hands-down, like, "We got you because you're a good actor and you're an amazing hockey player. Not because you're trans." That was a really affirming experience for me.

I love how Jacob Tierney approached the casting process of Heated Rivalry. He really went beyond just "checking a few boxes." But between writing a book, starting a brand-new career in acting, and making your first short film (Pink Light) — all projects created by you, a history-making Canadian trans athlete; not to mention that these projects were all created for people in the LGBTQ+ community — it's just very exciting to see you included on this show. A show that's so popular right now, and is so queer, and has a gay showrunner, and has queer love story at the center. An out trans man who made history in professional hockey, and who's now an actor, director, and writer himself, it just feels correct that you were included on this show. I know it's not the sole reason, but it also feels so meaningful.

Yeah, the representation for that, for people who know my story and are looking in, it will be pretty amazing. And to have the show picked up by HBO Max. It's getting so much attention. To be part of it is a true honor. Jacob really just ran an amazing set. Him casting me… I'm really happy to be part of this. I have a lot of respect for him.

Even the supporting actors are standing out so much on this show. It's gotten so big. What is your reaction to this response that the show is getting?

It's amazing. I am really blown away by it, and I think it's a crucial story right now, too. The conversation around LGBTQ+ representation on the men's side is in a big reckoning right now with the banning of Pride Tape, and what's happened in Pride Night games, so this is a really great story to spark even more conversations.

Also, it's really nice to see hockey be "sexy," you know? Hockey is an amazing sport that I think deserves way more attention. The response to Heated Rivalry gives me a lot of hope. There's an audience for my stories, and the things that I want to tell. And that's epic.

Heated Rivalry season 1 is streaming weekly new episodes every Friday on HBO Max.