I'm gay, and recently I've started to feel very resentful or hateful towards other guys, the better-looking ones. I'm a bear in the community, probably not very attractive. They seem to have such an easy time getting dates or sex. My choices are slim unless I go to the city (I live in a small town). Even then, I don't get much notice.

I see these good-looking guys with boyfriends getting the most out of being gay. I see these videos and photos on YouTube and Facebook, and it just makes me hate them all so much. What should I do?

“Hate” is a big word — a worrying, dark word that is particularly loaded for men like us.

Hate makes people dangerous, and fueled violence is a daily concern for countless gay and queer men across the world. And sometimes — probably more often than we like to think — this violence comes from our own, from guys who feel as you feel. Are you someone the rest of us should be afraid of?

That’s a sincere question. Are you someone who, despite your feelings, will still be kind? If a gay man encounters you on the train or in a bar and offers some kindness, some care, a helping hand, will you respond with kindness in turn — a smile, a thank you? Or has this resentment and jealousy turned you against us, severing all hope of connection and friendship?

You need to ask yourself these questions — because hate is quite serious. The rest of my answer will teeter into the philosophical, but that’s OK. That’s where we must go.

My friend, I cannot change the harsh, punishing arena of gay life. Yes, it can be awful. I won’t pretend it isn’t a defeating and cruel place sometimes. It’s hard to feel validated or wanted in a community that seems so superficial, so obsessed with certain bodies and particular looks — a playfield rife with body dysmorphia, self-hatred, and self-harm. I wish I could spare all my friends from it. I wish I could spare everyone who, like you, writes in with frustrations about it. But I can’t.

I wish I could do something to make it better, and to some extent, I can — I can practice kindness and compassion in my own small circle, the little sphere of community influence I have, my personal friend group.

And I try to do this. I hang in groups that celebrate diverse bodies and champion our trans brothers and sisters, people who stand with all the cool gender-fuckers and anarcho-queers in our incredible, badass community. My social orbit is not a neutral thing; I actively shape it.

Here’s an example of that. Last year, I learned that a good friend was not a safe person for my other friends. When he drank booze, he overstepped boundaries and touched multiple people I cared about without their consent. Though he never did this to me, I had to break up with him as a friend and cease contact, because his behavior was unforgivable. I told him in clear terms why we were no longer friends and have not spoken to him since. It was so disappointing, but decisions like these matter. Though my sphere of influence is small, the people I bring together and the spaces I curate are things I have some control over, and I want everyone who meets me to feel safe and validated in my little pocket of gay life, my personal version of what it can be like.

I don’t want a monolithic crowd of traditionally fit, white gays with me: I like the bull dykes and punks and chubby bears and people who expand my perspective and challenge my thoughts. My life is better with them. Curating one’s social sphere is something everyone can do, and even though it seems like a small thing, it has a ripple effect. People notice.

But this work is limited. It’s hyper-local. My cultivation of a nice, friendly scene won’t make much of a difference to you, wherever you are. It won’t make any difference to gay men living in places where they can be arrested for sodomy, or worse. Where you live might indeed be isolated and lonely, and when you go to the city, you probably do encounter unfriendly, judgmental gays suffering from their own body dysmorphia and insecurities and projecting them onto others in a vicious feedback loop of shame. I believe what you write. I believe it’s hard.

It does not justify hating us.

Babe, the guys you see — online and in person — are people. They’re flawed. You have to start seeing these men (even the ones who don’t notice you, even the ones who seem to have it all, and even the impossibly hot guys on Instagram who always appear in exotic places and appear to have no limits on their credit cards) as members of your community, because they are.

The hotties and regular guys alike all had the same painful experience of growing up gay in a straight world; all of them realized, at some point, they were not what their parents, schoolteachers, classmates, or society expected or even wanted. Most were teased, shamed, and ridiculed when their true natures began to show. Kids, especially straight boys, have a nose for this stuff, an uncanny ability to detect desire and softness, often before we do — and kids can be cruel. Nearly all gay men share the trauma of living in the closet, and most of us have trauma from coming out of it. These are near-universal gay experiences, and yes, sometimes they result in mean, judgmental, deeply wounded adult gay men.

And sometimes not. Either way, few of us are exempt from this trauma. We are all lost boys.

There is a saying in 12-step that I think is ever relevant: Hurt people hurt people. My dear, we are all hurt people. You are a hurt person. How you live with that hurt, and what you choose to do with it, defines the kind of person you are — and since you’re feeling hate, you need to sit and decide who you want to be. What will you do?

Whether you realize it or not, you are a participant in the gay scene you describe. You are one of these men — by virtue of being gay like them — and you likely share some version of this painful, universal queer experience with them. It’s a shame that shared experience is not enough to get a date or land a hookup — or even get noticed in a bar — but it’s not. But it is enough to love them.

I’m not meaning to make myself sound like a shining saint of goodwill towards all; I get jealous and competitive as much as everyone else. But I do not feel jealousy and competition quite as strongly as I did before I started training in compassion — as you must do.

It’s as simple as this: You have to choose to love gay men regardless of whether or not they fuck you, irrespective of what they do or don’t do. You must agree to love them even when they’re hard to love. You must decide to view the mean, petty things they do as the side effect of the same traumas you have, the after-effect of being a hurt little boy just like you.

Cultivating that love is not easy. You must direct it first at yourself, and this is the most challenging part. This is radical self-compassion, radical self-love — a difficult thing for most people. But you must try. Be curious about yourself — explore the peculiarities of your own mind and your own body. Observe where feelings of anger and jealousy live in the body. Try to love yourself even on days when it’s hard to love yourself — some days will be more successful than others — and, even when that fails, imagine radiating love outward to everyone around you.

I do this seated, with my eyes closed, as a daily meditation, but you can do it just walking down the street, or on a bus or train. Imagine something that symbolizes self-love — most people picture a warm light — and let it slowly fill your body, then imagine it spreading outward to everyone on the street, bus, or train. Then push it further, to all gay men nearby, then ones further away — men you may never meet, men just going about their lives. Try to make your love so big that it covers all of them. Send them all a little light, a little love, then refocus, come back to the present, and continue with your day. With practice, I promise the heavy things you feel — resentment, jealousy, anger — will get a little lighter.

Some years ago, I realized someone had to love gay men unconditionally, so why not me? After all, so few people do: Gay men are still the butt of so many jokes. We are so easy to mock, so easy to put down, so easy to summarize and deride and judge—usually by our own. So let me state for the record, now and always: I love gay men.

I love them when they’re messy and mean, when they’re rude, and when they make ignorant and judgmental comments about my HIV status, my kinks, or my body. I love their culture, their camp, their music, their art, their problems, their parties, and their pain. I love them because they’re family. Everyone has a messy family member; guys like us have many messy family members. That’s OK. I still love them. I have to.

Yes, this sounds lofty and woo-woo and a little New Age. But it’s necessary for you, because you feel hatred, and people notice that. Humans have an extra sense, a wariness, around those who hate — and if you’re feeling it, others feel it around you, and it will destroy all possibility of connection, for sex or more.

Luckily, the opposite is also true: If you feel love, you invite love. If you feel compassion, you bring it out. Humans have an extra sense for this, too. People struggle to describe this special sense, so we resort to simple language: “He’s kind”, “She’s lovely,” or just “They have great energy.” In the U.S., my friends would say “good people” as a singular adjective, as in: “I love Karl, he’s good people.” It was confusing at first, but in time, I realized there was no higher compliment, no better thing a gay man could say about another. I wish every gay man would aspire to be “good people.”

What these phrases grasp at is an inner thing, and it’s no mystery what it is. It’s compassion. It’s love. Cultivating these things requires an agreement to love others even when they disappoint, even when you have to stop talking to someone, even when you must let someone go. It’s not an agreement made with anyone in particular: It’s made in yourself, with yourself, for yourself.

Buddy, you have to do this. Because you’re in danger — and if you keep hating, so are the rest of us.

Only one thing is strong enough to beat hate. And here’s where I’ll get cringey and write the sappiest, most bumper-sticker thing I’ve written, because it’s true. The hippies knew it, and the rest of us are slowly catching up: Love is the answer. Love saves the day.

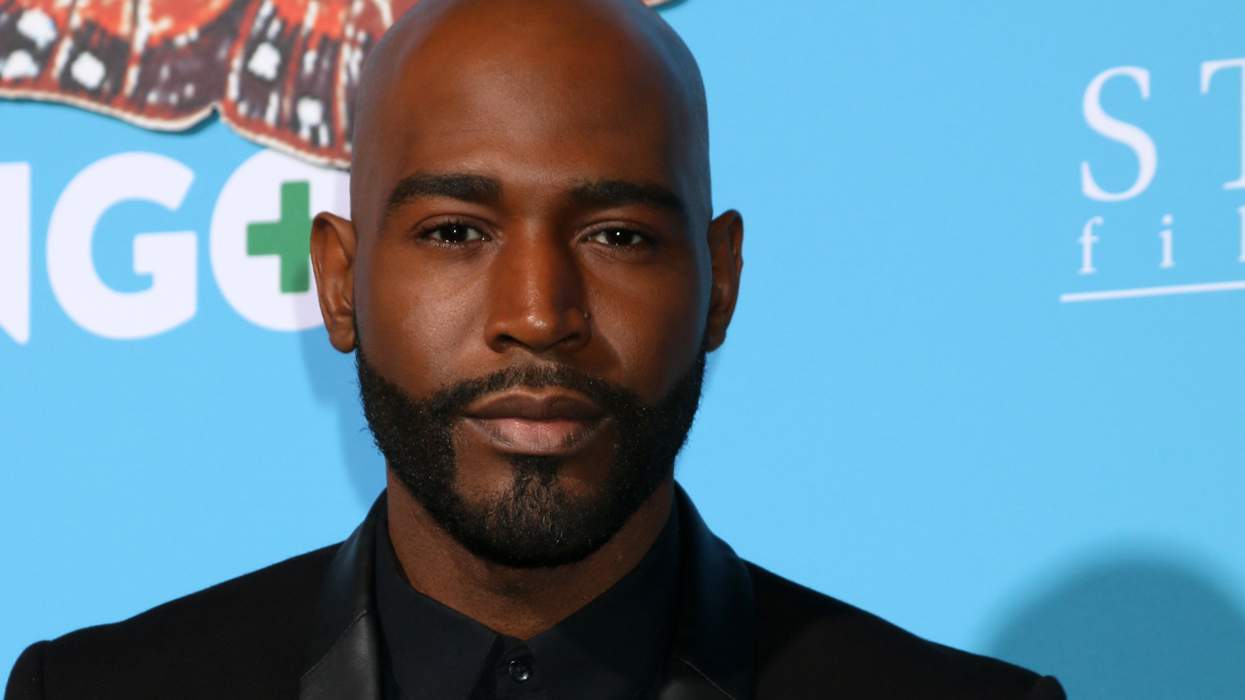

Hey there! I’m Alexander Cheves. I’m a sex writer and former sex worker—I worked in the business for over 12 years. You can read my sex-and-culture column Last Call in Out and my book My Love Is a Beast: Confessions, from Unbound Edition Press. But be warned: Kirkus Reviews says the book is "not for squeamish readers.”

In the past, I directed (ahem) adult videos and sold adult products. I have spoken about subjects like cruising, sexual health, and HIV at the International AIDS Conference, SXSW, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and elsewhere, and appeared on dozens of podcasts.

Here, I’m offering sex and relationship advice to Out’s readers. Send your question to askbeastly@gmail.com — it may get answered in a future post.