Hi Alex,

I read your article in Them about the use of the word “queer.” It prompted a question I have, though it’s not exactly related to it.

I am gay and understand coming out. I never came out because I was lucky to live in a home where I was just gay from the moment I started school. I would frequently tell my parents which boys were cute in my class, as far back as Kindergarten.

But I get it, some people come out as gay, lesbian, bi, and trans. But why do people come out as "demisexual" or "sapiosexual," for example? How did these labels become part of the queer movement?

Do you have to be LGBT to be a demisexual? As a gay man, I honestly only enjoy sex with people with whom I have a connection, but I never thought of myself as demisexual. And, I don't think any human is attracted to every other human that fits their sexual orientation, so isn’t everyone sapiosexual? Why is this now an LGBT term? When did the LGBT movement include “sapiosexual”?

Also, I noticed on social media that you ask people to include their pronouns when sending you questions, so that you can address them properly. I don't want to be an ass, but we address people by "you, yours, yourself, etc". If you are talking to someone, you don't say "he, his, him" to that person.

I don't believe in giving pronouns because, in my mind, it means permitting someone to talk about you to someone else, because that's the only time you would use third-person pronouns — when you are talking about someone, not to someone.

But anyway, what's your take on coming out as "demisexual”? And how is this similar to coming out as gay or trans?

Thanks, Anthony

Hey Anthony,

You’re not the only gay man who feels confused — maybe even a little irritated — by all the new labels. Sometimes it seems there’s a new one every year. It can feel like identity overload.

Let’s start with some quick definitions for readers who might not know them. Demisexual describes people who only feel sexual attraction after forming a close emotional bond. Sex and relationship therapist Karen Pollock puts it simply: the term “describes feelings, not behaviors.” Demisexuals can have sex, relationships, and attraction across genders, like anyone else — they just don’t experience that initial spark without emotional connection.

Sapiosexual, meanwhile, means being attracted to intelligence more than physical appearance — drawn to someone’s mind, not their body. Depending on who you ask, it’s a valid identity or a pretentious way to say “I like smart people.” (I’m only half joking.)

You’re asking something I hear a lot: When did terms like these become part of the LGBTQ+ conversation? Why do people “come out” as demisexual or sapiosexual the same way others come out as gay or trans?

It’s a fair question, and it points to a bigger truth about how language evolves. If it feels like new labels are being spun out of thin air, they kind of are — but that’s how language works. It stretches, splinters, reforms. Sometimes this happens out of necessity: People need words to name experiences they couldn’t describe before. Sometimes it’s just because humans like categories, especially when we’ve felt unseen. Think about how people feel relief when they finally get a medical diagnosis — naming something makes it real, manageable. Complicated things like disease and desire get easier once they’re named.

The debate over which identities belong in the LGBTQ+ acronym has become an online sport. Every few years, we cycle through the same tired questions: Do kinksters belong in it? Asexuals? Demisexuals? The debate is endless — and, to be honest, mostly pointless.

Back in 2018, during one of those “add new letters” moments, I wrote in The Advocate that including “K” for kink “runs the risk of oversimplifying identities like ‘lesbian’ and ‘trans’ to sexual fetishes — a claim we’ve been fighting for decades — and assumes all kinky people are queer (they’re not).” If I wrote that piece now, I’d add: Who cares? The people arguing about it online are rarely the ones fighting real political battles.

At its best, queerness is an ethos — a way of living differently from what society expects and values and a shared memory of those who were punished for it. If you’re demisexual or sapiosexual, great — use the words that feel true — but that doesn’t necessarily make you queer. Queerness, to me, is about risk and alliance. It’s not just who you sleep with; it’s how you live and who you stand with when trans rights are under attack.

In that Them essay you mentioned, I quoted sociologist Jason Orne, who describes three overlapping meanings of “queer.” The first is “queer” as an umbrella term — an all-inclusive shorthand for anyone who isn’t straight or cisgender. (This is how many LGBT publications, including this one, use it.) The second is “queer” as a leftist sociopolitical stance and a rejection of fixed identity categories.

“I say this usage is leftist because I’ve found it associated with a kind of ultra-left political critique of power structures which often appears, as I and others have pointed out, like a profound misreading of Foucault,” Orne says in that piece. “This is the queer you’ll see at a queer political event, a queer with an identity politics that often says, paradoxically, that the truth about an issue can only come from someone with the correct combination of marginalized identities to speak on said issue. It’s paradoxical because these queer leftists are usually white, and they pepper their events and issues with a kind of ‘diversity by numbers’ approach.”

Lately, these are disparagingly called “tenderqueers.” Orne calls this approach “queernormativity,” where people invent a “right” way to be queer and argue everyone else is doing it wrong.

The third “queer” Orne defines is my kind of queer: the irreverent sex radical that finds freedom and joy in what the world says is shameful. These are faggots, rule-breakers, the ones playing in backrooms and building new worlds of pleasure. They might not even use the word “queer,” but they live it.

Each group uses “queer” differently, which is why the discourse is so messy — but that keeps it alive and vibrant. Queerness was never meant to be neat.

So when you ask, “When did the LGBT movement include sapiosexual?” The answer is: It didn’t, not officially or in a way that matters. You’ll find people who say it did, and others who think “kink,” “furry,” and “witch” belong too. None of this keeps me up at night.

The real question is: When push comes to shove — when queer and trans people are under threat — will all these self-described queers show up? Will gay men? Will bi folks? Because that’s what makes someone part of this family, not the label. If they don’t stand with us, they can keep their words and fuck off. I’m protective of this community — of gay men, trans folks, queer women, and everyone still figuring themselves out — and I don’t have patience for anyone who wants the cultural cachet of queerness without the responsibility of solidarity.

You also raised a point about pronouns, which I’ll touch on quickly. You’re right that I write to people, not about them. But knowing a reader’s pronouns tells me something about their gender identity—how they move through the world, what risks they face, and what advice might help. Asking someone’s pronouns isn’t really about grammar; it’s about respect. The more we ask, the less invisible trans and nonbinary people feel. That’s the point.

Anthony, I get where your question is coming from. Many gay men of a certain generation look at the explosion of micro-labels — demi-, sapio-, omni-, and so on — and feel alienated. I feel it too sometimes. I came up when it was hard enough to say “gay” or “bi” out loud.

But younger, relentlessly online generations grew up with language as a playground. They’re exploring their inner worlds online, publicly, and they want precision. They want to name the nuances of desire we used to shrug off or bury. That’s not wrong, just different.

For older folks who fought through the plague years and the marriage equality battles, it can feel like watching your hard-won identity get rewritten in a dialect you don’t recognize. For younger ones, it can feel like trying to build a new language under the judgmental glare of those who came before. Both sides get something right and something wrong.

So yes, I understand the eye-roll when someone “comes out” as sapiosexual. But behind every label, new or old, is someone trying to be understood. That’s a prehistoric human impulse — it’s what all our myths and fables boil down to: What am I? Every time we try to name what we are, we make a little stab into that mysterious dark called desire and try to draw from it some shape, some clarity. And desire never fits neatly into language — it’s always one step ahead, constantly surprising us — but the effort to name and understand it is shared by all.

I’ve never found a word that perfectly fits me. I say “gay” because it’s simple, but sometimes “pansexual” feels truer. Neither tells the full story. Our words are just tools — blunt, imperfect ones — to understand ourselves.

So what’s my take on coming out as demisexual? Do it. If a label helps you understand yourself, it does its job. You don’t have to be LGBT to be demi or sapiosexual, and identifying that way doesn’t automatically make you queer. But it also doesn’t hurt anyone.

The alphabet soup is messy and imperfect, but its only real purpose is solidarity. The full, shifting LGBTQ+ acronym is a linguistic effort at unity aimed, however loftily, at unity in the voting booth and on the streets — it exists because humans find safety in numbers. You’re allowed to think what you think, Anthony, but you can’t police how others name themselves, especially when it costs you nothing to let them exist.

In the end, our words — gay, bi, trans, demi, sapio, whatever — help us feel less alone. We can debate which ones belong, or just let people use their words and go about their lives. Go about your life, Anthony, and don’t worry about demisexuals. They’re not bothering you.

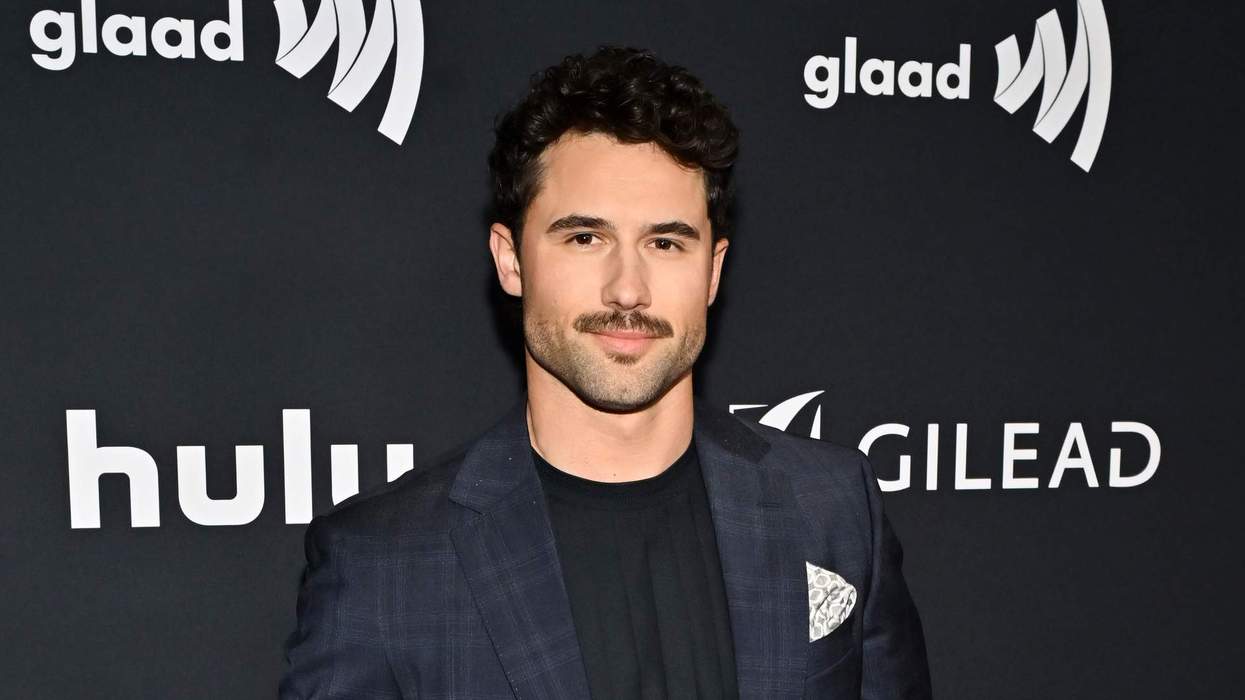

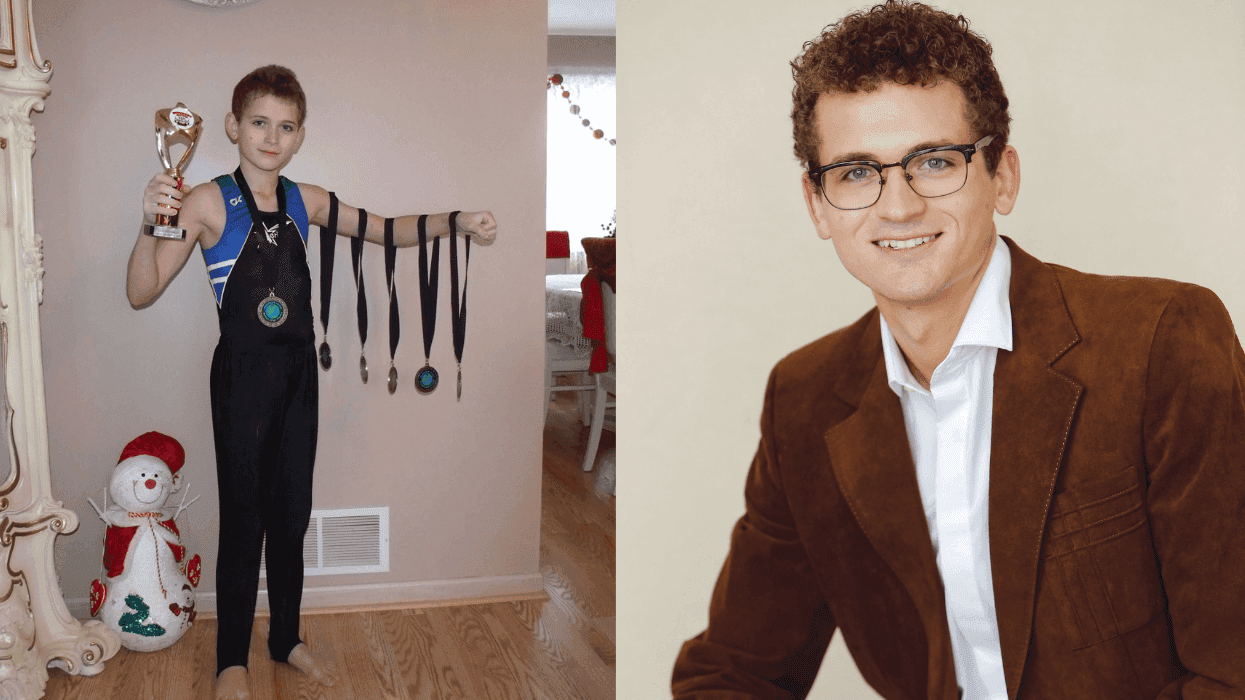

Hey there! I’m Alexander Cheves. I’m a sex writer and former sex worker—I worked in the business for over 12 years. You can read my sex-and-culture column Last Call in Out and my book My Love Is a Beast: Confessions, from Unbound Edition Press. But be warned: Kirkus Reviews says the book is "not for squeamish readers.”

In the past, I directed (ahem) adult videos and sold adult products. I have spoken about subjects like cruising, sexual health, and HIV at the International AIDS Conference, SXSW, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and elsewhere, and appeared on dozens of podcasts.

Here, I’m offering sex and relationship advice to Out’s readers. Send your question to askbeastly@gmail.com — it may get answered in a future post.