The rafters drip with dangling flower decor. Carnaval-themed lights wash the patio in shades of magenta and teal, and the glitter painted on the waiters’ cheekbones flickers whenever they turn their heads, adding to the kinetic, kaleidoscopic atmosphere. Law Roach, the evening’s emcee, gets on the mic and introduces a special guest. The special guest is…Cher. Her appearance prompts a seismic shock wave of gay gasps in all directions.

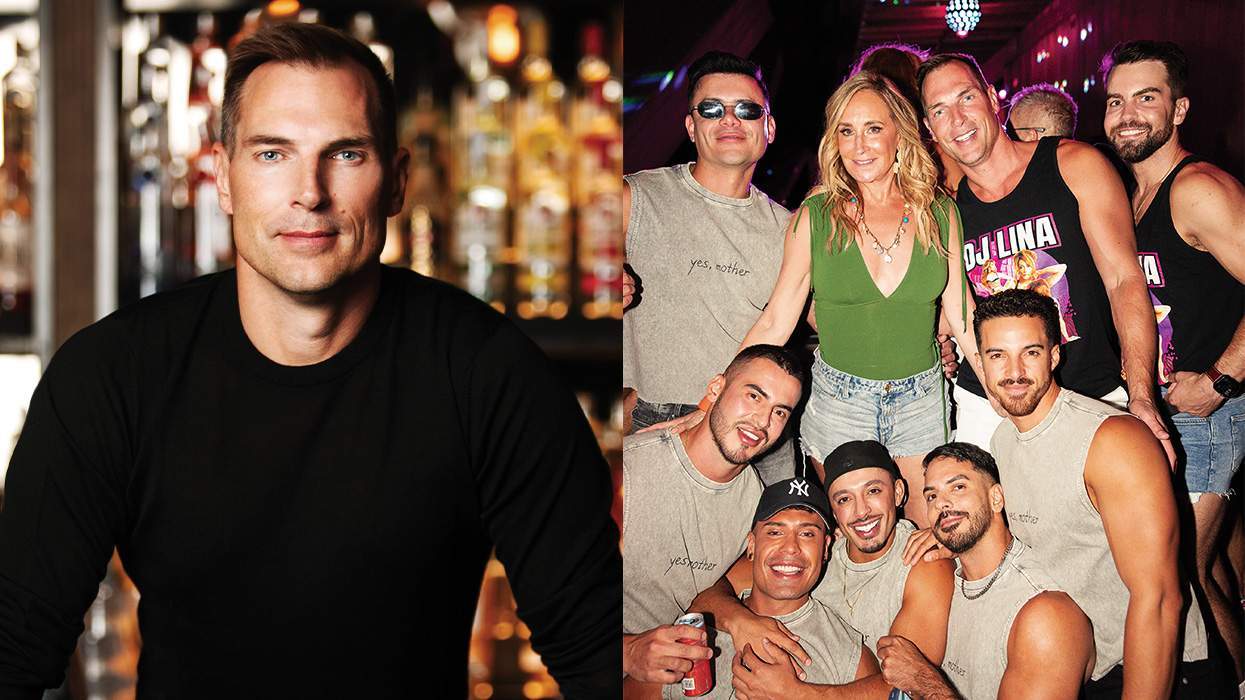

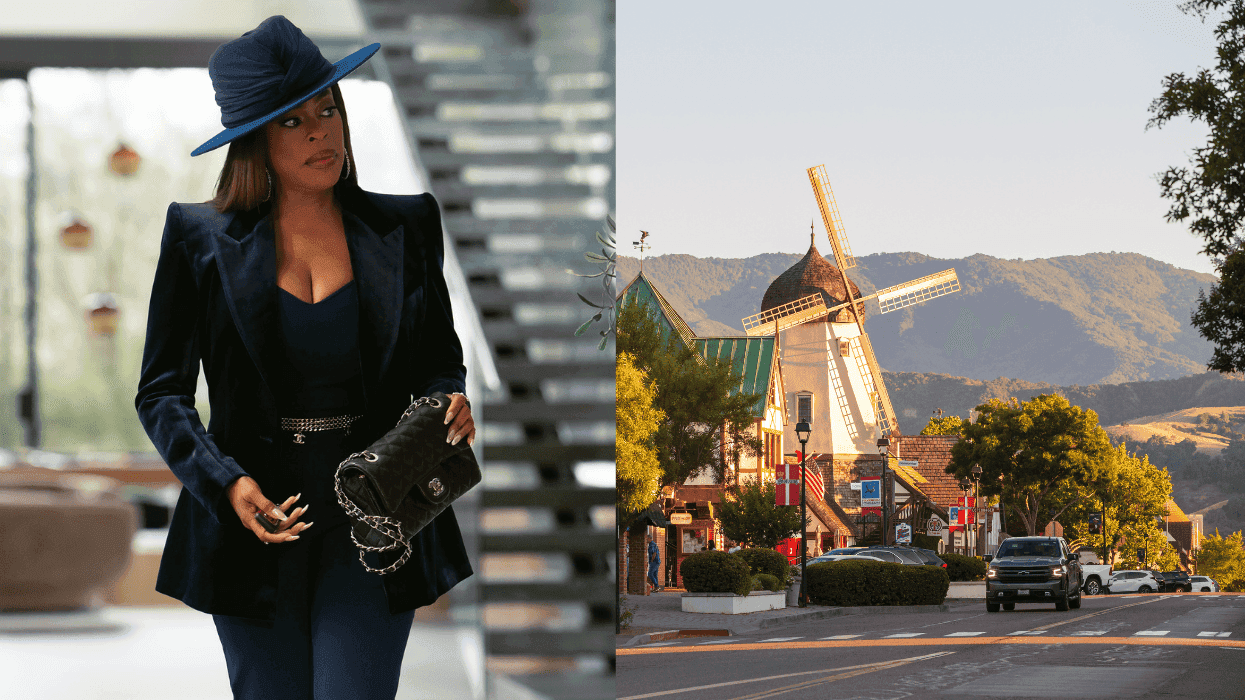

It’s the relaunch party of The Abbey, the famed and sometimes controversial gay bar in West Hollywood that opened as a coffee shop back in 1991. Special appearances and surprises, as promised, roll in throughout the night; shortly after I meander to the dance floor, rap superstar Saweetie takes the stage. “We love you, Tristan,” she says before launching into a performance of her hit single “My Type.”

“Who the fuck is Tristan?” blurts out a drunk gay next to me. And that feels like the question of the evening. The relaunch is to commemorate a baton pass in The Abbey’s ownership from founder David Cooley to Tristan Schukraft, a relative newcomer in queer hospitality ownership.

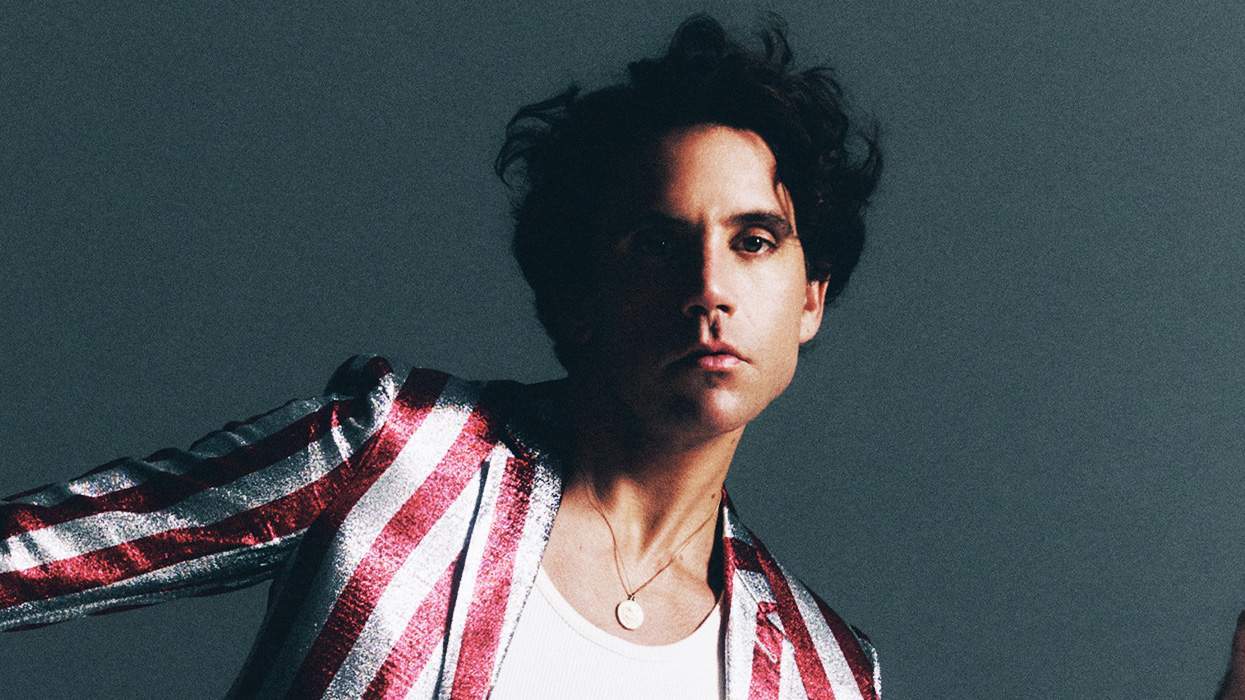

A bit of a technology wunderkind who also first worked as a model, Schukraft launched his first software company at 21, helping the airline industry migrate to digital solutions like e-ticketing. He’s now 45, and his newest venture is Tryst Hospitality, a collection of properties and related businesses catering specifically to queer leisure. In just over two years, Schukraft has acquired the Circo nightclub in San Juan, Puerto Rico; an entity that owns a hotel in Puerto Vallarta; a 75 percent stake in the Fire Island Pines Resort commercial district; and The Abbey and the adjacent club, The Chapel, which sold for $27 million. The Abbey is a large operation, having a headcount of 275 employees in 2021; the bar banned bachelorette parties in 2012 until same-sex marriage became legal three years later, and on separate occasions both Lyft and Uber named it the number-one nightlife drop-off and pick up spot in America by rider volume.

In the spring of this year, Schukraft also added the first Chicago property to his portfolio, buying DS Tequila for an undisclosed amount from founders John Dalton and Stu Zirin. “I started in Boystown working when I was 22, and now I'm 47,” Dalton told me in a phone call. “I love creating queer spaces, but after 25 years of doing the same thing, I really wanted to end on a high note, send [DS Tequila] off in safe hands and open a new chapter in my life.”

Dalton said he thinks Schukraft can help bring an international twist to Boystown. “I'm very happy I sold to someone who it seems can withstand the business cycle of a bar and restaurant. It’s an overwhelming business to be in, and the business cycles can be extreme, especially in Chicago, where you don't have as steady a stream of international tourists and need to be really focused on your local market. Market Days in Chicago has become internationally famous, and we need someone to help push that and make it bigger and better, just like how WeHo Pride has become this monster that attracts people from all over the world.”

“He can bring that to Chicago,” Dalton added.

Deep pockets aside, Schukraft’s experience from software CEO to hotelier prepared him for this high-pressure moment. After a brief, unsuccessful stint in politics with a run for West Hollywood City Council in 2013, he ventured into gay media with Frontiers magazine. Later he serendipitously found himself in public health with the launch of the PrEP telemedicine start-up MISTR. That company bled money for years before achieving critical mass; it recently surpassed 350,000 patients. He says he always wanted to be like Richard Branson and build a megabrand like Virgin. It would seem the California native is closer than ever to achieving that goal.

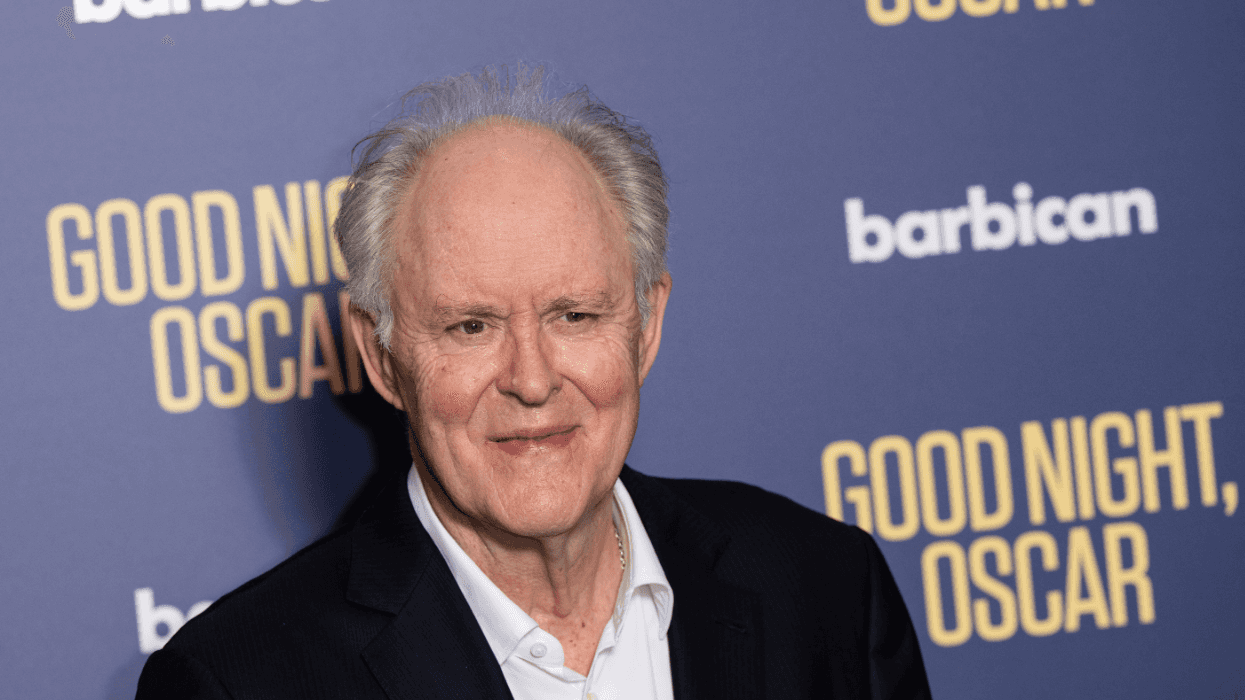

But can he hold a pace that’s never been seen before in queer hospitality? And what’s the real motivation behind his Bransonesque aspirations? I met with Schukraft for an interview at The Abbey to find out.

This interview took place May 31 and has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Out: Your first business was selling scooters?

Tristan Schukraft: TS: I was living in Hong Kong modeling at the time, and my boyfriend had broken up with me, so my life was over. My dad told me to come home and offered me $10,000 to pursue a trend that had come up at the time: Razor scooters. So I bought all these scooters, thinking they were the Tickle Me Elmo of the day and I would sell them out in like two weeks. It took longer. I would be at the swap meets at 5am to get the best spots, I would be outside the schools, outside office buildings, anything. I sold my last six scooters on Christmas Eve. It was not a long-term thing; it was a short-term thing to capitalize on a fad and raise some capital, as well as prove to both myself and my parents that I could actually do it.

After that, I started ID90, which was basically like an Expedia for airline personnel. My whole family was in the airline business, so I had the pleasure of traveling the world practically for free my entire life. And there was this book of discounts for airline employees, where you got like 50% off or whatever [on flights and hotels], but a lot of the rates weren’t competitive anymore. Everyone was going online.

The business model was that you had to negotiate these good discounts, but you can’t negotiate really good discounts if you don’t have the members, and you can’t get the members if you don’t have the discounts. Then 9/11 happened, and I thought to myself, “Oh my God, I’m totally fucked. This business is over.” But that’s when the business actually took off, because hotels were empty. Hotels hadn’t been returning my phone calls, and now suddenly they were empty, so any idea they could find to fill their rooms was worth pursuing. I grew that company to 111 employees and operations in nine countries.

A few years later the Oneworld alliance came to us. They were introducing a new fare program, and they wanted me to build a calculator for their employees to be able to put in origin and destination and calculate fares. But as I was sitting in this conference, listening, I was like “You have a bigger problem here; it’s this e-ticketing thing.” I was like 25 at the time and everyone else was in their forties and fifties; they were like “Who’s this smart kid trying to tell us how to do our jobs?” They told me to take care of the calculator and that they would take care of the ticketing. People were just so against e-tickets. Can you imagine flying without an e-ticket now?

Why were they resistant to e-ticketing? Seems obvious.

Well, they thought their job was to manage this paper process, and that e-ticketing meant their jobs would be going away. You don’t need a team of 55 people to do something that can become automated, right?

So I doubled down on it. I was 25, I had just bought my own house, and I went out, raised some money, and leveraged it all. I needed an airline to prove my concept, but no one would sign on. People would be attacking me in meetings. It was horrible.

Finally, at one conference, my sales director came up to me after a presentation and said a woman in the back wanted to talk to me. I was like “Oh God, here we go, another person bitching me out.” But she loved it. She was with Hawaiian Airlines, and we had a contract the next day. It was my first airline, and after that the rest started rolling in. That deal happened in Puerto Rico actually, which is crazy because I ended up back there 15 years later for Tryst.

I ran ID90 for 14 years, and then we hired a CEO to take it over and sell it, but it never got sold. It was one thing after another; the housing crash, COVID-19. So I still own a percentage of the company, I get my dividend checks, but I don’t run it anymore.

Not a bad spot to be in.

I’ve raised $18 million for that company, which is a lot of money. But I was also on the road all the time. Offices in nine countries, across four continents. I flew about 30 hours a week, around 600,000 miles a year, so that was my life for a long time.

Ironically, I was living in LA at the time, and we had an office in Argentina, so I would fly there every Sunday, and remember sometimes thinking to myself, “I just want to go to The Abbey!” I moved to WeHo in 2011.

Tell me about your run for West Hollywood City Council in 2013.

I lived in Argentina for three and a half years while with ID90. I thought the city of Córdoba was so poorly run. There’s a saying: “Argentina is the country of the future – and it always will be.” I’ll never get over that. It’s so corrupt. Every seven years there’s an economic crash. It’s like clockwork. I thought about running for mayor of Córdoba someday when I was done with ID90, but after three and a half years I’d had enough of it and got out of there.

So I got involved in politics here. I thought WeHo was always pretty well run, but like anything, things could be done better. I ran for office, and I’d never worked so hard in my life for [essentially] a volunteer position. You get $800 a month, and then you get a parking pass where you can park anywhere, which is kind of gold in West Hollywood. I don’t have a car, though.

I didn’t win. I registered to run again next time, but then I didn’t go through with it because I was selling Frontiers magazine at the time.

What drives you specifically about politics?

I think it's my annoyance with inefficiency. You can't complain about things if you're not willing to do something about them. I had the time, I was home and I wanted to do something different. I thought I could make an impact, that was my main motivation.

What I learned in that process is that government is so bureaucratic. It drives me crazy because I'm used to running my own business. While I'm very collaborative, at the end of the day it's my decision. I’m not afraid to make decisions – I’m a risk taker, I’m very decisive.

After ID90 and before Frontiers, I consulted for a couple of corporations. What I noticed was that the executives in the C-suite of a corporation are there to increase shareholder value, cover their ass and get their bonuses. They're not willing to take any big leaps of faith – they're not risk takers.

How did your involvement with Frontiers come about?

I met Michael Turner, who bought it, and I later invested in the company. Frontiers was the second-oldest gay publication. We had this room downstairs, and it was basically an archive, like a time capsule…. They chronicled everything, the AIDS crisis, gay rights….It just wasn’t doing well, and I thought I could turn it around. I think solving a problem is what kind of motivates me about business.… It was a tough business. But you do get invited to every party when you own or work for a magazine.

I’m discovering that as well.

Print media just can’t compete with digital media. In digital media, you can show cost per acquisition, right? There is value in print media, it's good for branding, we participate. We support the LGBT publications because those organizations are giving the gay community a voice. But do I get a lot of return on investment? No.

For print, getting people to advertise was really tough. Then after you meet the sales target for that issue, you have to start all over again, which is exhausting. We ended up selling into a publicly traded company that was basically consolidating gay media companies, and after we sold it went out of business, which was really unfortunate because it was such an important publication.We ended up selling into a publicly traded company that was basically consolidating gay media companies. And after we sold, it went out of business, which was unfortunate because it was such an important publication.

Next we come to MISTR, which you previously told me was a business you weren't looking to start.

After we sold Frontiers, a couple of organizations came to me and said, “Would you help us start a PrEP program?” A lot of people I knew complained that it was really hard to get on PrEP. I was invited to join the [commission on HIV] here in L.A. I went to these meetings and met a lot of really amazing people…some of whom had lived through the crisis.

With MISTR, we had to recognize the differences in what people want…. A lot of people don’t like going into a doctor’s office. The drug has always been free; it’s the lab visit that’s not free. The hardest part is the cost of the doctor’s visit and the labs.

There was no business plan for MISTR. I just started helping people, and then helping one person became 10 and then 100. I hired my first employee, a developer who was a former employee of ID90…. We launched MISTR at Palm Springs Pride, set a goal of 300 sign-ups, and got 375.

We were fronting the cost of the labs, so we were burning cash for many years. I would joke with my friends about how I’d make more money sitting at home doing nothing than running this company. But we’re not losing money anymore, and we passed 350,000 patients this month.

What has tipped MISTR into being profitable?

Achieving critical mass. I think that's where we are right now. We're in a really good spot. We also never rest on our laurels – I mean, we're constantly marketing.

People say, “I see MISTR everywhere now.” We really do market constantly. I think we have a really good brand name and good customer base. Some companies might release the gas pedal a little bit, but every month I insist on minimum 5 percent month-over-month growth, and right now we're doing about 12 percent.

In some ways, having more patients makes it easier, and in other ways it makes it harder. When we started we would do Grindr ads. We’d get 600 signups; now we get like 200 signups, because you're milking the cow too much, so to speak. Now we have to be more creative on how we reach our audience.

Over the last few years, you've become a hotelier and have been on a bit of a shopping spree. Why now? Was it your vision for all this to become an interconnected gay hospitality universe before you started?

I’ve always wanted to be Richard Branson and have a brand like Virgin. I had moved to Puerto Rico by this time…. Hurricane Maria in 2017 destroyed that island. There were no jobs. A lot of the gays just left.

So I’m there with my friend on the gay beach and there was this parking lot on the shore. I was like, Why is this a parking lot right here on the beautiful coastline? I called my Realtor and asked if it was for sale, and it wasn’t because it was already going to be converted into a hotel. But they did say the hotel next door was for sale.

I looked up, and the name of the hotel was Tryst, which was my childhood nickname, albeit with a different spelling. I was also drawn to the logo but couldn’t put my finger on why. “You know why you like that logo?” my friend said to me. “Because it looks like the Virgin logo.”

Then there was Circo, which I realized was like The Abbey of Puerto Rico. I knew that even if we created a gay beach club with a rooftop bar, people want more than that. They want a destination. People don’t come to West Hollywood just for The Abbey; they come to barhop and be in the area because there are lots of things to do. So we scooped up Circo.

Later I was visiting Puerto Vallarta. There’s this hotel near the beach that had been under construction for six years. I knew they had to be out of money. I asked them if they were selling. They’d always say no, but I kept asking…later we’d closed the deal.

Then, a couple [of] months later, Fire Island [Pines Resort commercial district] went up for sale.… It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, so I pounced on that. For The Abbey, I wasn’t necessarily looking…. I had been working with a Realtor in Hollywood, and she reached out to me to let me know the bar was up for sale.

It wasn’t my intention to do this all at once. But there are benefits when it comes to hotel operations – centralized accounting, centralized marketing, centralized IT – that have economies of scale. I can have a reservations department of employees now because they’re managing multiple hotels.

And with DS Tequila, it seems like you’re still not done.

Again, DS was a great opportunity to preserve the community. John and Stu ran it for 14 years, they ran a series of bars around Chicago. This generation of LGBT entrepreneurs, these founders, they're all retiring. So if someone doesn't step in, we're gonna lose these institutions, they’re going to disappear. I'm really fortunate. I think we have a few more opportunities for property locations with Tryst. I want Tryst Hotels to be a hub for the gay community, so that means knowing the local community because every market is unique.

When I went to raise money for Frontiers, nobody would invest in a gay company. That…was a motivator for me. I’m trying to prove people wrong and show that I can build a gay hotel. Even when we were promoting the gay hotel, a lot of people [in media] were like, “Well, we don’t want to write about a gay hotel.” Why? There are family hotels. If I’m flipping through Travel + Leisure magazine, and I see something about a family hotel, I’m going to flip past it. If I’m straight and I don’t want to read about a gay hotel, I can do the same. It’s not offensive.

We are in the hospitality business. We are that escape for people, their vacation, what someone has worked 50 weeks out of the year to go and do. It’s our job to make sure they have the best time ever, and if we’re not doing that, shame on us.

Nick Wolny is Out magazine’s finance columnist. He also writes Financialicious, an email newsletter on LGBTQ+ business, finance, and culture. NickWolny.com @nickwolny

This feature is part of Out's September/October issue, which hits newsstands on August 28. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Apple News, Zinio, Nook, or PressReader starting August 13.