If you don't see lesbian history, you have to make it yourself.

That was the ethos of revolutionary filmmaker Barbara Hammer, who made over 80 avant-garde films in her life and is the subject of the new documentary Barbara Forever. Part lesbian history archive and part love letter to and from the artist who passed away in 2019, the film, from director Brydie O'Connor, should be added to the canon of film, gender studies, and queer studies curricula.

In the film, Hammer explains that she didn't hear the word "lesbian" until she was 30, and when she did, she had no idea what it meant. As soon as she embraced the identity, she realized that she had never seen lesbian sensuality or sexuality on screen, and decided to put it there herself.

Once she started, she didn't stop until the end of her life, making over 80 films and being a part of the New Queer Cinema revolution along with filmmakers like Gregg Araki, Todd Haynes, and Cheryl Dunye.

The film continues to explore her career throughout the 80s and 90s, all the way to the 2000s and 2010s when she documented her aging body and life with cancer.

Barbara Forever is largely about lesbian love, and interviews with Hammer’s long term partner, Florrie R. Burke, overflow with adoration and admiration for the late trailblazer. It’s beautiful to see long-term lesbian love celebrated this way.

Because the film is largely composed of Hammer's own archival footage and films, it has the physical and sensual feeling she described as an innate part of "lesbian cinema." It feels tactile, which makes the lesbian history even more real and present.

It's important for lesbians and sapphics to learn their history. Without it, we can't sustain our community and we can’t grow. This becomes evident when you see young queer women online arguing over whether or not trans men should be included in lesbian spaces.

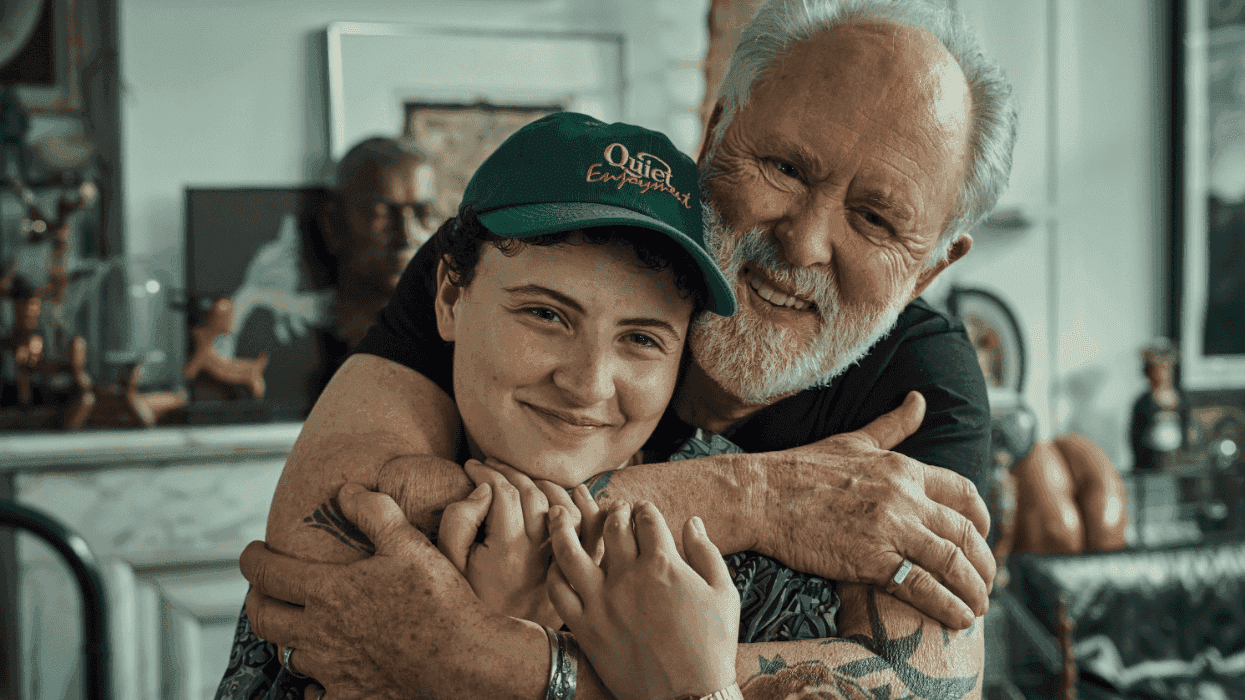

Barbara Forever easily and empathetically answers. One of the relationships highlighted in the film is the friendship and professional collaboration between Hammer and Joey Carducci, a much younger queer filmmaker. When the two met, Carducci was identifying as a lesbian.

Showing clips from Carducci's film A Video Letter to Barbara Hammer, Carducci explains that he was scared to come out to her as trans masc, fearing she would see it as anti-lesbian, anti-woman, or anti-butch. Carducci says he wants to explore transmasculinity not in opposition to lesbianism, but in community and solidarity with it.

These issues aren't new. The lesbian community has been intersectional since it began, and hopefully, when some people see this film, they'll understand that we are in solidarity with trans men, not against them.

Barbara Hammer’s legacy, and this vibrant and important record of lesbian art, isn’t just secured with this film—it’s forever enshrined.

This kind of movie is even more vital now than ever. As the government tries to erase queer history from schools and government files, we need to make sure we are creating our own archives, just like Barbara did.

Out Review: 5 out of 5 stars