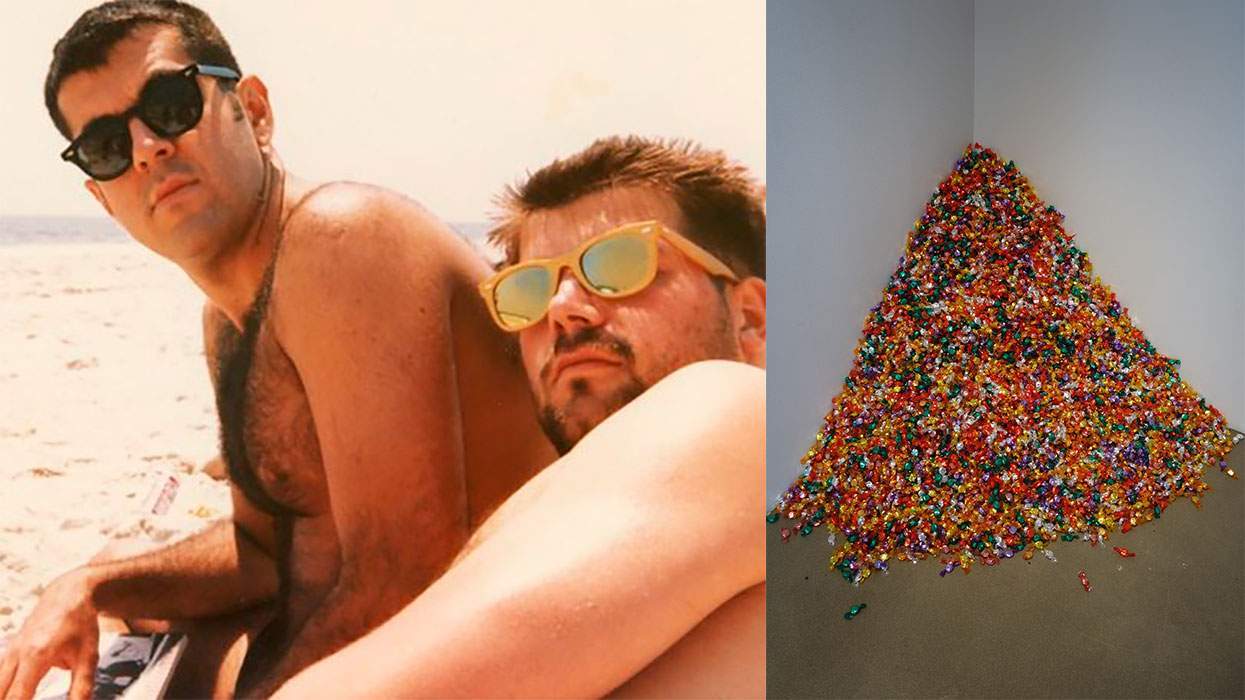

I'll never forget my first "chillout." I was new to London — a huge, vibrant, and gay city compared to the tiny Scottish town I grew up in. I was fresh meat learning what the city had to offer, as well as its biggest secrets.

It was a Friday night in summer, and I had met a hot guy while clubbing with mates. Five a.m. rolled around, and he invited me to an afterparty around the corner. I followed him to an apartment building in Soho, and we went straight up to the top to a big, stunning penthouse flat.

But as I walked in the door, I realized it wasn't like the afterparties I had been to before.

Inside, I found what seemed like 100 gorgeous guys, all having sex in different rooms. It was a full-on porn scene, but with a distinct difference: Guys were mixing drinks with a clear liquid in syringes in the kitchen, and there was a weird smoke in the air that didn't smell like a cigarette or a vape. I don't know whether it was horniness or intoxication — but, naturally, I took off my clothes.

The original guy I had met disappeared, so I started making out with someone else. That was when I suddenly felt a horrible, scalding sting on my chest. I looked down to see that he was holding a lit pipe, which had accidentally burned me and singed my chest hair. Instinctively, I knocked the pipe out of his hands, and it smashed into a million glass pieces all over the floor. The naked muscly men all started running around freaking out… And that was my cue to leave.

Years later, I've become much less naive. The scar on my chest eventually faded. I've learned what "H&H" meant (high and horny). I've realized that 'G&T' (GHB and tina) didn't always mean gin and tonic. By now, I've seen it all and even tried some (most) of it. Today, my eyes are firmly open to the underground culture of chemsex embedded in gay nightlife in big cities like mine — a culture described as "chillouts" in London, despite ironically nothing being chill about them.

To my surprise, it was Instagram-perfect, high-earning lawyers and doctors who were in the deepest: out from Friday to Monday, hooking up, scrolling through Grindr, partying on GHB, mephedrone, and crystal meth, going from flat to flat. I would hear stories of friends "G-ing out" (overdosing on GHB) and waking up in an ambulance. Or, worse yet, those who never woke up. I'd see heartfelt sympathy messages on Instagram in their memory but no real explanation for what happened. No one was willing to address the elephant in the room.

I also saw that, even if chemsex didn't immediately impact their lives or physical health, there was a significant mental-health toll for those in the deepest. Whether it was losing their jobs, facing financial turmoil, or breaking down through relationships, the long-term comedown was real.

From my own experiences in the gay nightlife scene in London, I can attest to the fact that chemsex has a tight grasp on my community, and it seems to be getting tighter.

The tricky thing about tackling chemsex is that, similarly to past health crises in the LGBTQ+ community, there aren't many systems inherently built for us. If governments treated chemsex more like a public health issue rather than a criminal one, it'd reduce harm and allow for more judgment-free support. For instance, funding safe drug-checking services, specialized clinics, and LGBTQ+ organizations would be steps in the right direction.

I eventually discovered Controlling Chemsex and learned that it was a grassroots organization run by medical professionals who help people struggling with chems. Its founder, Ignacio, spends his weekends operating overnight "helpline" profiles on Grindr in the "Tina Triangle" (a chemsex hotspot area in London) for people to message and get support — whether it is advice on what to do if someone is overdosing, or to share kind words to a person who's experiencing a low moment. Ignacio also has a team of doctors who provide harm-reduction advice, connect people to clinics, and offer pathways to addiction support. Organizations like these need more funding and recognition.

Until governments and their systems catch up, we must lean on one another to stop chemsex from ravaging our community. Many people can dip their toes in and out of it when it suits them, but those are the lucky ones. Many others cannot.

If you have a friend whose sessions are lasting longer and longer, check in on them. If you're going to an afterparty at 5 a.m., be prepared for what will likely happen. And if you are personally struggling with any of the issues I've raised, then please know this: There is life after chemsex, and there is support available for you.

For more information and access to free support, visit ControllingChemsex.com.

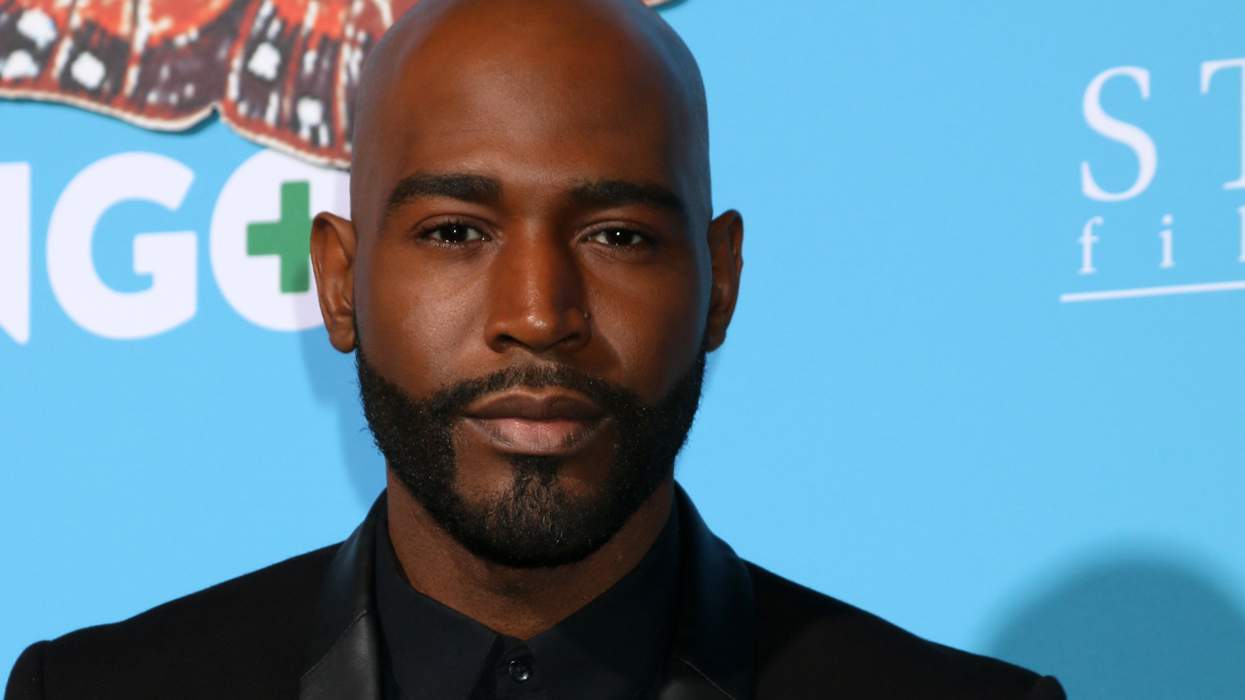

Dan Harry, a contestant on the U.K.'s first-ever gay dating show I Kissed a Boy and a presenter of the BBC documentary HIV, PrEP & Me, works as an LGBTQ+ sexual health activist. According to a new study from Controlling Chemsex, "75 percent of the queer community doesn't understand the severity of chemsex."

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.