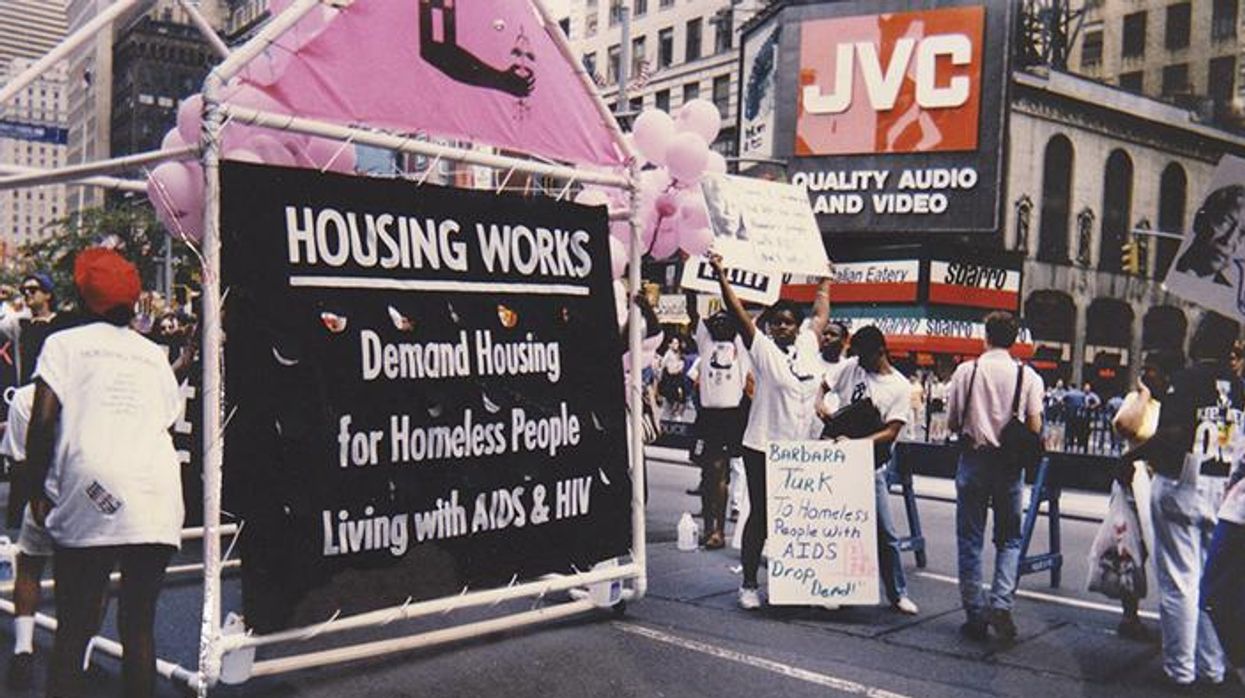

I catch AIDS in 1987. I'm not sure exactly how but I've definitely caught it, so I'm definitely going to die: horribly and soon.

I'm 11.

"Act normal," I tell myself as the advert that's been going round the playground finally comes on the TV. Our living room is full, as usual, with my mum and Dodger on the armchair, and Joe, Shawn, Tricia, and Aidan on the couch with me and Teenie on the floor in front of the telly.

"There is now a danger that has become a threat to us all," begins a plummy English voice. On the screen an obviously papier mache mountain explodes and I've seen better special effects on Terrahawks. "It is a deadly disease and there is no known cure." Joe shooshes Tricia, who is crying because Aidan nipped her. Teenie would rather be outside playing, but it's dark, so she starts girning and I nip her, which I never do, and she's so shocked she actually shuts up.

"The virus can be passed during sexual intercourse," and we all snigger and I join in even though I feel sick inside. More shooshing. On the telly a workman's hands chisel a word out of black stone and chapel bells ring doomily. "Anyone can get it." Anyone, yes, but. "Man or woman. So far it has been confined to small groups. But it's spreading."

I am in that small group; I must have it already. I look at the cream rug I'm sitting on and see the AIDS spreading out from me like a stain. "So protect yourself. Read this leaflet when it arrives. If you ignore AIDS, it could be the death of you. So don't die of ignorance." The workman's hands finish their work and the epitaph is complete: aids. I see my name on the tombstone as it falls towards the grave.

The leaflet arrives the next morning along with the usual FINAL FINAL demands and the latest catalogue for Uncle Joe who orders goods he'll then sell at the pub and deny were ever delivered. A real entrepreneur. So here I am waiting by the letterbox. 15 Rannoch Avenue is bad enough without AIDS. I'm lucky I'm unpopular because Mark is the only pal I'd dare bring here. He stays every Friday night. We barricade my bedroom door and read the latest Stephen King. Lately we've been getting into fantasy, too, and we're working our way through Gormenghast. In all these worlds it's me and him against everybody else. Mark doesn't care that there's no vinyl on the concrete scullery floor that's silvered with slug trails every morning. I wish we had a dining table where everybody sat down for meals and talked. I'm mortified by our out-of-fashion Venetian blinds. The least I can do is stop AIDS coming into our house.

That Easter at church, or maybe chapel, I learned that the Jews painted their front doors with lamb's blood to make the plague pass over. I am the first-born son in this house. It's probably already too late for me, but maybe I can spare the others, stop them catching it. Already I take my toothbrush to bed to stop anyone else using it, by accident. Shaving is years away but if I make it there I'll hide my razor. Anyway, the only lamb I've ever eaten starts life frosty in the freezer so daubing the door with blood is a no-go.

Maggie Thatcher says AIDS is a threat to national security. I scan the leaflet quickly: "There is no cure. And it kills." I stuff the leaflet in my schoolbag, sling it over my shoulder, and run out the door just as my mum comes downstairs. As I run round the corner to the black steel gates of Keir Hardie Memorial Primary, I imagine her sobbing over my grave. It's a comforting thought. Maybe grief will bring her and my dad back together? I won't be there to see it, but at least I'll get the credit.

As always, Mark is easy to find: He's showing off at elastics with the girls. He's the only boy that plays. I don't get the appeal of knotting together hundreds of differently colored elastic bands and stretching them between their shins to form a complex web that one of them jumps through while the others sing a stupid song. "She is handsome, she is pretty, she is the girl from the golden city," they chant as Mark nips between the tiny spaces, avoiding painful pings and getting faster and faster with the rhyme. He shoots me a look that says wait. They shout the last line: "How many kisses did you get last night?" At that he leaps out the elastics to applause and runs over to me before any of the girls can claim their kisses.

"Shhhsht," he says. I spot an identical leaflet sticking out of his pocket.

"We've got IT," I hiss, as if this will stop us getting IT. We sneak out the playground and sit on the quiet steps of the school clinic where we went for the bollock cough check-up, where I was worried I'd go hard when the doctor touched me.

"I know," he shrugs, seemingly unbothered.

I can't believe this. We're dying and he doesn't care. Mark is brave enough to dive off the highest board at the swimming baths -- he's the only pupil in the history of the whole school ever to do it. Without blinking he torpedoes the deep end and the bubbles in his tunnel of speed are beautiful. But this is taking bravery too far.

"What are we going to do?" I panic, jabbing at the leaflet so hard it rips.

"Die," he says, laughing and skipping away.

"It's not funny," I shout, running after him, careful to pocket the leaflet. "I don't want to die. I want to go to Brannock and... and -- "

"And what?" says Mark, pulling me close in a way that would look like a headlock to anybody walking round the corner.

Danny, Kev, Mark... all that carrying on in the dark. That's what will kill me, kill us all. "Most people who have the virus don't even know it. They may look and feel completely well." I feel fine, apart from asthma. But what about the spots I've started getting? The birthmark on my neck that everybody calls my love bite, has it changed, is it a lesion? I run my finger over it and feel tiny bumps. Were they there before? "Those most at risk now are men who have anal sex with other men." I know what an anus is, mainly from Tanya the Rottweiler, that belongs to Dodger's pal Andy. Her tail was docked too high so her brown-pink arsehole winks at everybody all the time. But what is "anal sex"? Does a finger count, a tongue, an ill-advised Action Man? What exactly is "seminal fluid"? Is this the mythical spunk that all the older boys brag about?

"Listen," says Mark, trying to calm me down. "If we've got it, we've got it and the leaflet says there's nothing we can do. There's no cure and that's that. We'll just have to die. But it says here it only affects adults. We're not adults yet -- well, you're not."

Recently Mark sprouted pubes, and we all saw in the changing rooms at the baths, so now when the school grass gets cut we stuff our trousers full of cuttings and run round shouting, "Bushy." Mark was first, as always. The only activities I beat him in are academic, and even then he's not far behind.

Weeks become months and suddenly we're in our last term at Keir Hardie Memorial Primary School. Soon we'll no longer be the big ones in a school of wee ones. Neither of us is dead yet but Mark has full-blown acne and we worry lots about that. Could his spots be a symptom? For a while we cease shenanigans, but one Friday night we just can't stop ourselves. Might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb, as Granny Mac would say.

Granny Mac gets all the papers on a Sunday, which means the Sunday Mail and the News of the World, and spends hours tutting deliciously and pointing out especially filthy stories to my Granpa, who is only interested in football and horseracing. One Sunday I am scrunching the screws, as Auntie Louisa calls it, for kindling and read a story about Tom Jones being a sex addict who cleans his cock with Listerine to stop AIDS after all-night romps. Minutes later I'm in my granny's bathroom feeding my cock into her mouthwash. Aesop's clever crows and their pebbles, I think, as pink flesh displaces green liquid. It burns! Oh it stings like nothing else. I turn on the cold tap and splash my cock, but it only makes it worse. Tom Jones must taste minty, I think as I top the mouthwash up with water and put the bottle back in the medicine cabinet.

Only when I'm brushing my teeth at home that night does it click that Granny and Granpa Mac must be doing the same.

I'm top of my class most years. When it's not me it's Brian Southlands because he's better at maths and some years are more mathsy than others. All marks in all tests, except PE, are added up because we're all competing for the Dux medal. "Dux comes from the Latin noun for 'leader,' " explains Mr. Baker. We take more tests than usual for the Dux. Reading is all Mark and I do when we're not at school, well almost. We spend ages in Newarthill Library and enjoy it all the more because none of the boys who call us names ever come in there. Doesn't stop them hanging round outside to get us on the way in or out. When we both turn 12 our green junior library cards will finally turn yellow for adult and all the James Herbert and Stephen King books we sneak out now will legitimately be ours.

Instead of doing maths, me and Mark master the mambo. As soon as Dirty Dancing comes out, we swoon for Swayze; we want to put Baby in a corner so we can have him all to ourselves. The attitude! The hair! The hips! Mark and I take turns getting the video out of the shop, pretending it's for my sister. Nights we should have spent clicking at calculators and puzzling with protractors are dedicated to working out the exact steps. Pause, rewind, play. Pause, rewind, play. We bicker over who gets to be Johnny and who gets to be Baby and decide to take turns. Somehow along the way we accept we are, well, completely gay. We've both been called "poof" enough to get the message.

"Actually I'm bi," Mark insists, citing his deep love for Kylie Minogue. We found out about bisexuality when Freddie Mercury from Queen admitted he liked men and women in Granny Mac's News of the World. I say I'll try being bi, too, so we're both the same. Maybe being bi will make us less likely to get AIDS. All these worries are secondary to the need to get those dance steps down. After acing his BAGA exams, Mark can do the bending backwards to touch his ankles with his head thing -- a skill certain to be useful in later life. I can only watch and wince but I'm getting better, dropping my clumsy act and convincing my limbs they can actually coordinate. One day we decide to practice on the water pipe spanning the burn that runs through Newarthill and on through New Stevenson to Holytown and beyond. In places it's three feet deep and it's where shopping trolleys go to die. OK, the pipe over the burn isn't a log over a river in America but, with no fear of the 20-foot drop, Mark ignores the warning sign and scissors his legs over the barbed wire, being careful not to catch his now hairy balls. I pass him the ghetto blaster containing the precious cassette and I don't look down as he helps me over. With great seriousness we take up our positions to re-enact the bit of the film I'm surprised we didn't wear out watching. In our thin elasticized plimsolls we grip the pipe, get our balance, and then Mark clicks play and we dance and we dance. "1,2,3, 1,2,3," Mark counts over and over and we repeat the lines of the film backwards and forwards till we are Johnny and Baby. We only snap out our Swayze haze when we notice we're not alone. Standing on either side of the pipe are some boys. They're the same boys who wait outside the library. They dance around, bending over for one another, shouting, "Poof, pansy, AIDSy," and, just for me, "Barbie." The cassette stops with a click. The mambo is over. We're trapped.

Without speaking, Mark and I look at each other, grab the ghetto blaster, and drop into the fast-flowing water. We scream at the cold and laugh as it carries us away sliding over rocks and dangerously close to a trolley and the boys shake their fists in frustration like baddies in the movies. When they're well behind us we grab some grass and drag ourselves out, shaking with cold and fright.

Watching out for them we run back to Mark's, singing, "I've Had the Time of My Life."

Maggie & Me (Bloomsbury USA) is out April 8.

Illustration by Blair Kelly