Twenty years ago, I boarded a plane from my native Bahamas, knowing I would never see it again. I was living in a glass prison. I could be anything, but I knew I couldn't be queer. How could a place filled with so much beauty have the potential for so much pain? Could "paradise" be poison?

Technology has allowed me to feel less far from home. I can make video calls with my sister, who lives near the beach, or share photos with high school friends on WhatsApp. It's not a curated vacation spot for me; it's the actual people there that keep me grounded. The Bahamas I love still seems to be there, but I often wonder if it's waiting for me.

"So you never coming back?" my brother asked on a previous call. "Probably no," I responded.

Feelings of liberation and grief wash over me when I think about my decision to file for asylum. Liberation, as I get to live my life entirely queer as a lesbian and love my wife unapologetically. Grief, as I realize I could only live "free" outside the country I grew up in.

I played by the rules; I remained closeted in the Bahamas because, all around me, I saw examples of what life could be like if I came out. I still remember the protests when Rosie O'Donnell launched her gay family cruise. Those loving gay families were met with a sea of people with a megaphone screaming, "Marriage is between a man and a woman." Most Bahamians gave a stamp of approval for the protests. I still remember the people crying, "Tell Rosie O'Donnell to take her filth elsewhere."

Was I filth? I remained silent and afraid.

We have been indoctrinated since birth, by every politician, priest, and pastor, that the Bahamas is "a Christian nation." Having grown up on a heavy diet of weaponized biblical scripture, Billy Graham crusades and evangelical reinforcement, Bahamian citizens were ready to meet O'Donnell with their harshest dose of fire and brimstone.

There was little LGBTQ+ presence in the Bahamas at that time. It was just one activist standing on the front line, Erin Greene, with the now-defunct organization called the Rainbow Alliance. Everyone knew her name on our small island. I am grateful for her work and her indomitable spirit. When I reached out to her to ask if she could write a letter for my asylum case, she wrote, "homophobia in the Bahamas is deeply ingrained" and "attacks of murders of gays and lesbians are frequent."

After a string of murders in 2009, Erin left the Bahamas for a short time. She closed her letter by saying, "I stay in the Bahamas at great risk because I earnestly believe that here… progress on these issues is possible". Her exposure led to her ostracization at the time. The message was loud and clear: stay hidden.

So I suppressed myself tightly into a small box and bided my time until I found my place in New York, the birthplace of queer freedom.

I sometimes wonder if I left prematurely. Did I have the strength to fight? What if I had stayed? And has the public perception changed? Looking at the Bahamian media, I understand that the fight continues. Even in our independent nation, we have yet to shake the shackles of colonialism. While the Bahamas struck down the infamous buggery laws in 1991 decriminalizing sexual relations between same-sex individuals, there still aren't any specific protections for LGBTQ+ individuals.

The Bahamas Christian Council (BCC) is leading this charge. Founded in 1948, the BCC is a group of Christian leaders from across the denominations who promote Christian unity and values. Though the BCC claims they "support the right of each Bahamian to determine their own sexual preference," their relentless pursuit of queer Bahamians says otherwise. The organization's president, Bishop Delton Fernander, called a press conference last October to oppose the local university's Pride Week event, saying that it was an affront to the "morals, values and standards of the country." The BCC, like many, sees LGBTQ+ visibility as a threat. They want to wipe out any iota of homosexual presence.

The BCC's influence on the country's social and political life was abundantly clear, as recent as the 50th anniversary celebrations of the country's independence in which the Council was given a three-hour prayer service on national television. In chairs like thrones, they sat on a stage overlooking a sea of people as they prayed for the nation. Their stance also emboldened hate that turned to violence — something increasingly becoming standard across the United States.

Humanity is missing for a group that claims to promote God's love.

Today, queer Bahamians continue to seek asylum. The unimaginable loss for the island cannot be quantified. In my circles, I know a quantum physicist, a prolific writer, and a journalist, all of whom have brought their talents to another part of the world. I feel guilty for leaving some days. What could I be doing to move the needle forward?

As a filmmaker, I want to bring truth to life. I've delved into my isolation in the queer community of New York and went deep into LGBTQ+ history in America. My latest project is the most nuanced: a short visual story in collaboration with the Caribbean Equality Project, a community-based organization that empowers, advocates, and represents Afro and Indo-Caribbean LGBTQ+ immigrants in New York City. The film Caribbean Queen centers the perspective of a Caribbean youth who wants to be the queen of the West Indian Day Festival. This new project combines my two homes and truths into one powerful story celebrating liberation.

LGBTQ+ activists who remain in the Bahamas are stronger now than ever, and continue to pressure the government for equal rights. Most notable is Alexus D'Marco, one of The Bahamas' current leading Human Rights defenders. She is the Executive Director of the United Caribbean Trans Network (UCTRANS), the first Caribbean trans collective to advocate on behalf of the Caribbean trans community, which promotes the protection and recognition of the human rights of trans people in our region. The organization's determination and efforts give me hope that LGBTQ+ equality will come to the Bahamas and across much of the region. There is a generation of LGBTQ+ Caribbeans that want to make it better for everyone.

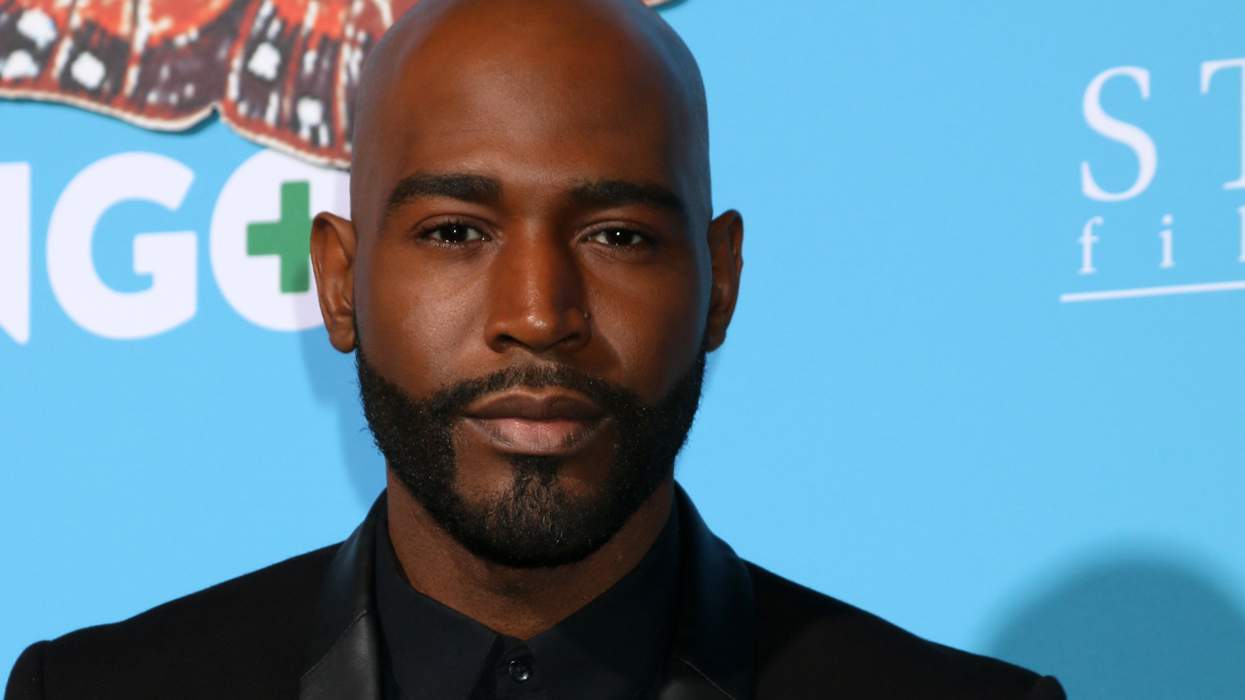

Sekiya Dorsett is an award-winning filmmaker and Assistant Professor of Film at The Lawrence Herbert School of Communication at Hofstra University. In 2019, she directed a four-episode documentary series, "Stonewall 50: The Revolution," for NBC News and NBC Out about the historic uprising at the Stonewall Inn, winning a GLAAD Media Ahe series won a GLAAD Media Award and an Excellence in Digital Journalism award from the NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists. Recently, Sekiya was one of the cinematographers who brought Netflix’s "In Our Mother's Gardens," a masterpiece of intergenerational Black woman confessional storytelling, to critical and audience acclaim. Her producing work took "Motherstruck," a web series featuring Gina Yashere (Bob Hearts Abishola) and Laura Gomez (Orange is the New Black), to the Tribeca Film Festival. "Caribbean Queen," a short film in partnership with the Caribbean Equality Project, premieres on June 7th during Brooklyn Pride.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit out.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. We welcome your thoughts and feedback on any of our stories. Email us at voices@equalpride.com. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists and editors, and do not directly represent the views of Out or our parent company, equalpride.