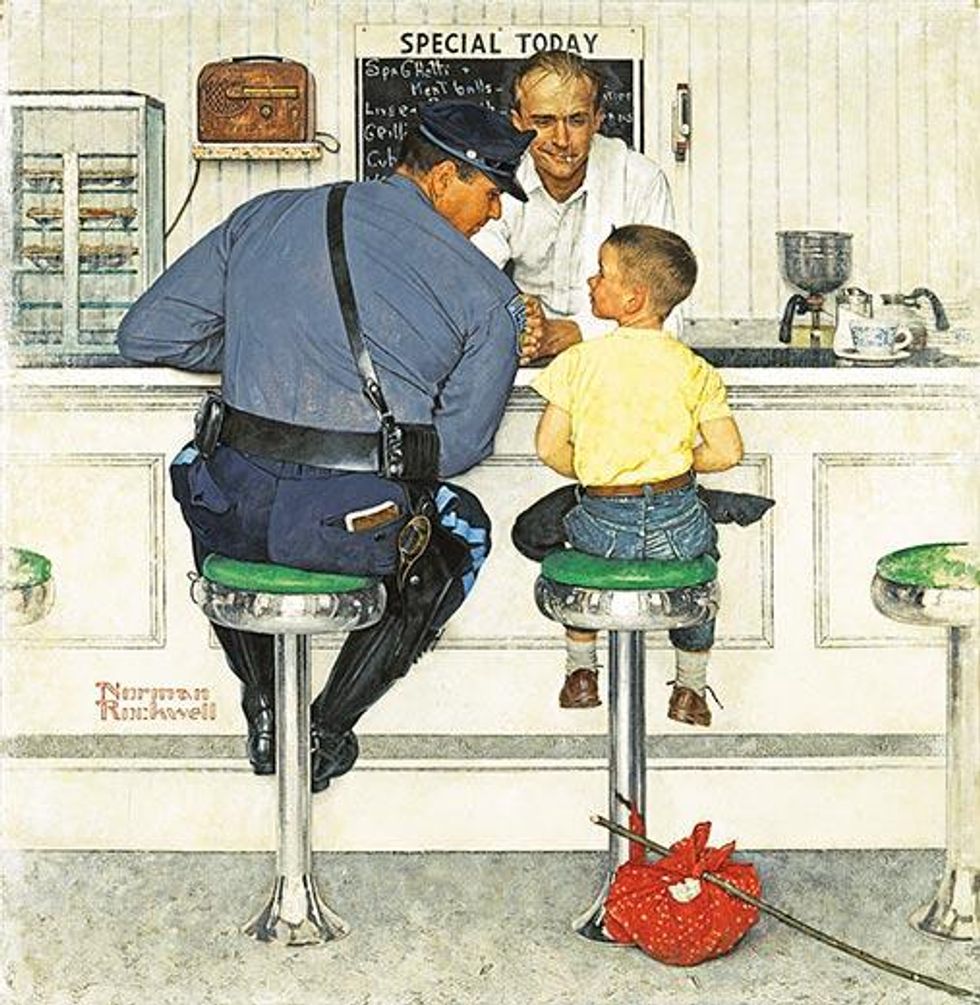

Norman Rockwell's "The Tattoo Artist," 1944. | Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the artist

In the midst of our current attempts to tamp down aggression and bullying, it may seem strange to consider that at the turn of the 20th century, as the population was rapidly urbanizing, America's male youth weren't considered masculine or aggressive enough.

It's one reason the Boy Scouts of America was such a success, spurring on a movement to make boys more macho. It's also why generations of boys were ruined by well-meaning attempts to "fix" them (as Throwaway Boy, this year's biography of outsider artist Henry Darger, also reclaimed as gay, portrays in heartbreaking detail)--which was the case for one of the 20th century's most cherished yet problematic artists, Norman Rockwell.

So much has been written about Rockwell, including his own autobiography, that his life would seem to be a closed case. But he receives a fascinating rethinking in Deborah Solomon's American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), in which she makes a clear case for his homoerotic desires.

Although she can't conclusively prove that Rockwell had sex with men, she makes a sound argument that he "demonstrated an intense need for emotional and physical closeness with men" and that his unhappy marriages were attempts at "passing" and "controlling his homoerotic desires."

Rockwell also had a close bond with the openly gay artist J.C. Leyendecker and his gay brother, Frank, also an artist, and counted himself as the "one true friend" the brothers had. As Solomon states, "it was both an artistic apprenticeship and an unclassifiable romantic crush." Rockwell went on to have close relationships with his studio assistants (even sleeping in the same bed with one on an extended camping trip) and created his own version of idealized boyhood beauty. The biography has angered some of the Rockwell clan, with the New York Times stating that two family members found the revelations and innuendos "shocking."