Choreographer Elizabeth Streb flings herself--and her dance company Streb Lab for Action Mechanics--at the very notion of a "protected class." As the new documentary Born to Fly: Elizabeth Streb vs. Gravity presents Streb's interest in what she calls "POPACTION," it shows her bonhomie with art figures like Bill T. Jones and casually glances at her home life with her partner Laura Flanders. This contrasts the amazing violence of her circus theater works that break elitist rules of dance propriety, same as she breaks bones.

Such a dangerous pursuit isn't new to the history of performance art (some of Streb's early '80s shows took place at the Chelsea art space The Kitchen), but her gravity-defying curiosity and dedication to a risky, defiant muse suggests a deeper story than director Catherine Gund eventually tells. Billed as "The Evel Knievel of dance," a physician opines: "Streb is an extreme example of a great athlete squeezed into artistic form." Gund traces Streb's trailblazing from years spent under the legendary Trisha Brown to Streb's most recent peak--a commission to open the 2012 London Olympics with awe-inspiring outdoor performances on both London Bridge and the London Wheel. But Gund's PBS American Masters-style trajectory (which unaccountably leaves out the business practicalities of performance art) stays superficial without ever asking, "Why?"

But everything Streb does asks why. An answer floats between scenes of the Action Mechanics troupe hurling themselves through space, swinging from truss straps or rappelling walls and Streb herself as she oversees the action with a perpetual look of fascination. Her pale, lined face, dark, spikey hair and black-frame eyeglasses have a Ludwig von Drake daffy intensity--different, friendlier, than photos and footage of her dramatically pretty youth. Streb's experience, her absorption of hard-knocks, is the point of her choreography and the story one feels even though Gund seems shy to tell it.

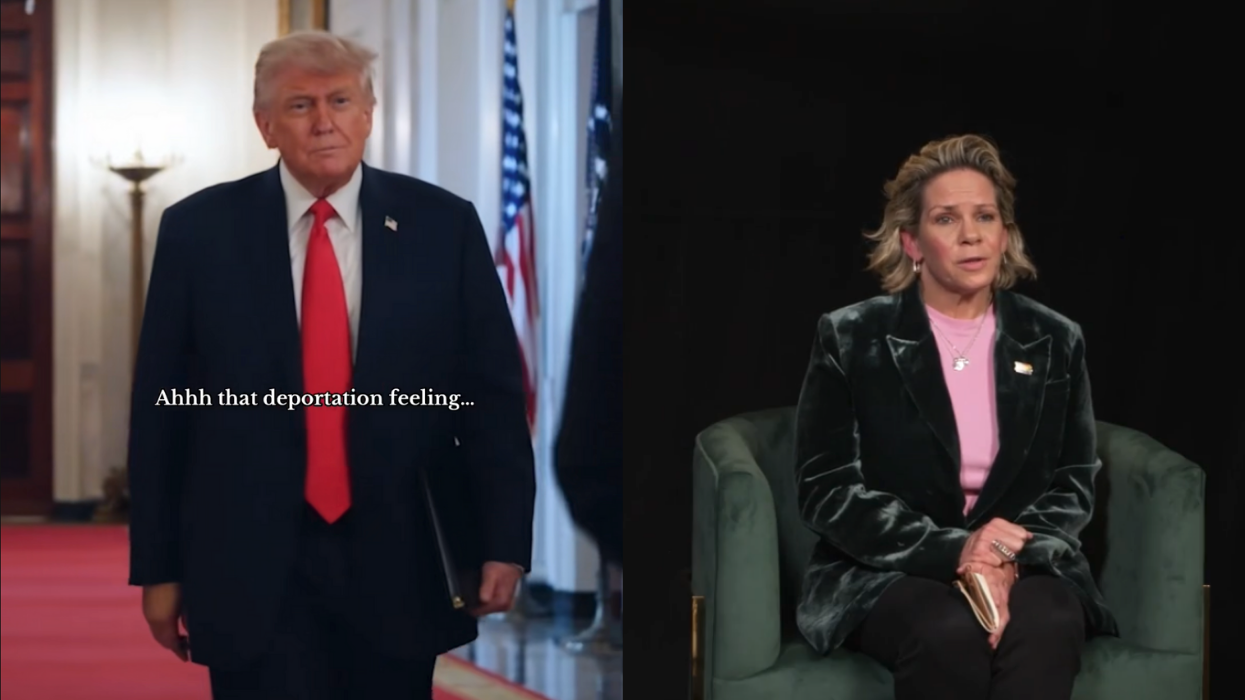

Streb (left) and her partner at home in their SoHo New York City loft.

There's a foolhardy, heroic displacement of the usual socializing urge in Streb's work as she gathers daredevils around her. Daring what heterosexual female artists rarely do, it's no surprise that Streb's chosen partner resembles Amelia Earhart or that many in her troupe seem mysteriously drawn to Streb's adventure/quest. ("Being careful in an action enterprise is really frowned on at Streb," says one.) The relentless responding to challenge, the daring to dare, suggests there's ethical determination and unquestioned strength such as defines an outsider's tenacity.

Even though it may look the opposite of the will to survive, Streb's personal art mission should be recognizable to all--but especially those in her audience and her troupe who gay-identify. Her dances suggests kinetic metaphors for the hard-knocks of gay social struggle. (It links to the homosocializing of the stunts in Jackass, an outlet for unexamined impulses.) What Streb asks of her dancers is scary--but fun, as Grace Jones sang.

"You're taking full-on force and its effect," Streb says and her point has sociological application proven by Gund's troupe interviews. For one young woman: "I felt like a wild horse; it celebrated my most powerful self." For a young man: "I like things with agility, the monkey thing." Another youth says: "Eventually you'll destroy yourself, but I was feeling pretty sexual at that time." And Streb salutes them with a mentor's admiration: "All these dancers that I have now are supreme performers and practitioners. These dancers are fliers and crashers and soarers, beautifully articulate with their bodies."

In her Look Up piece, Streb's dancers jump and smash against both sides of Plexiglass, resembling a prophylactic sex or modernist version of the mirror trick in Duck Soup. To Streb, it shows "knowing where you are is how you survive."

Describing a 1985 work, Little Ease, Streb calls it "my seminal solo that was really the purest idea of how much the body can do in that little space, when that's all you've got." Although the title Little Ease came from a medieval torture device, it's clear that the performance resists self-censorship and social restraint. If Streb doesn't get autobiographical about, it she doesn't have to--it's what viewers who have made this doc an art-house hit appreciate. Streb could find herself mobbed by kids who want to stop purging and cutting.

Streb's instruction could be advice to the lovelorn: "You have to get beyond the barrier of self-protection before you can really fly and do the moves. Your ability to navigate space and time--in a way no one's ever seen the body move--increases and increases and increases."

Born to Fly is currently in select theaters and opens in L.A. Sept. 26. Watch the trailer below:

BORN TO FLY: Elizabeth Streb vs. Gravity [Official Trailer] from Aubin Pictures on Vimeo.