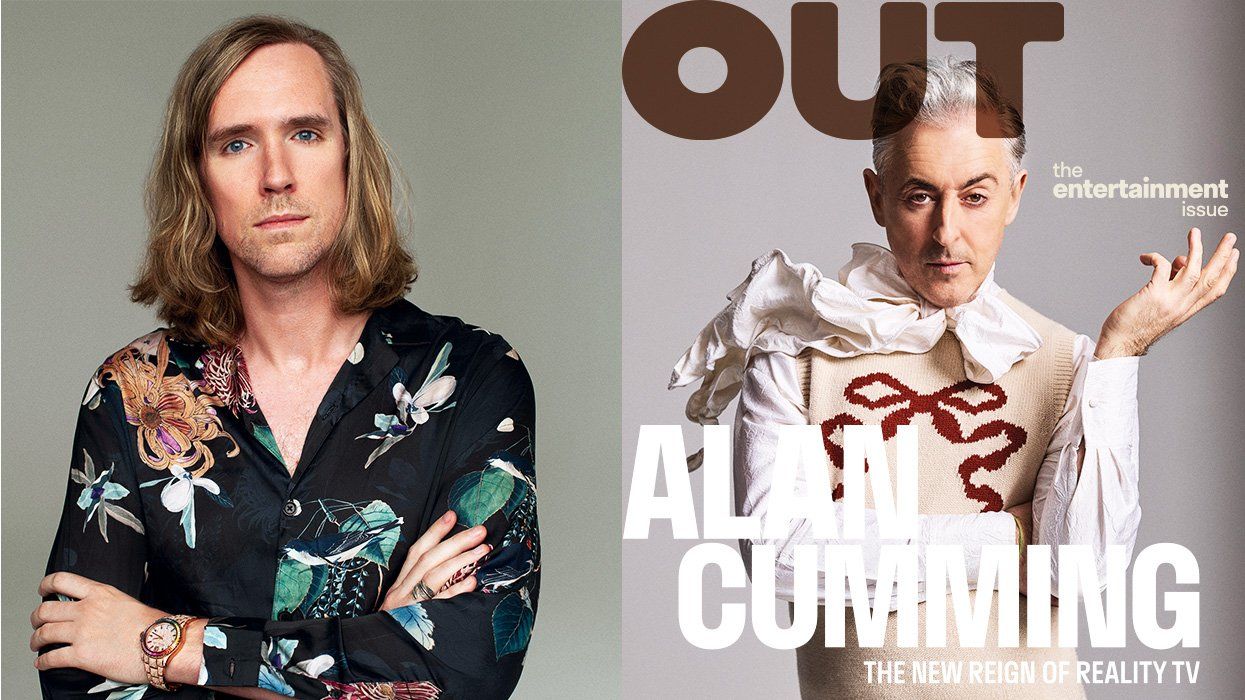

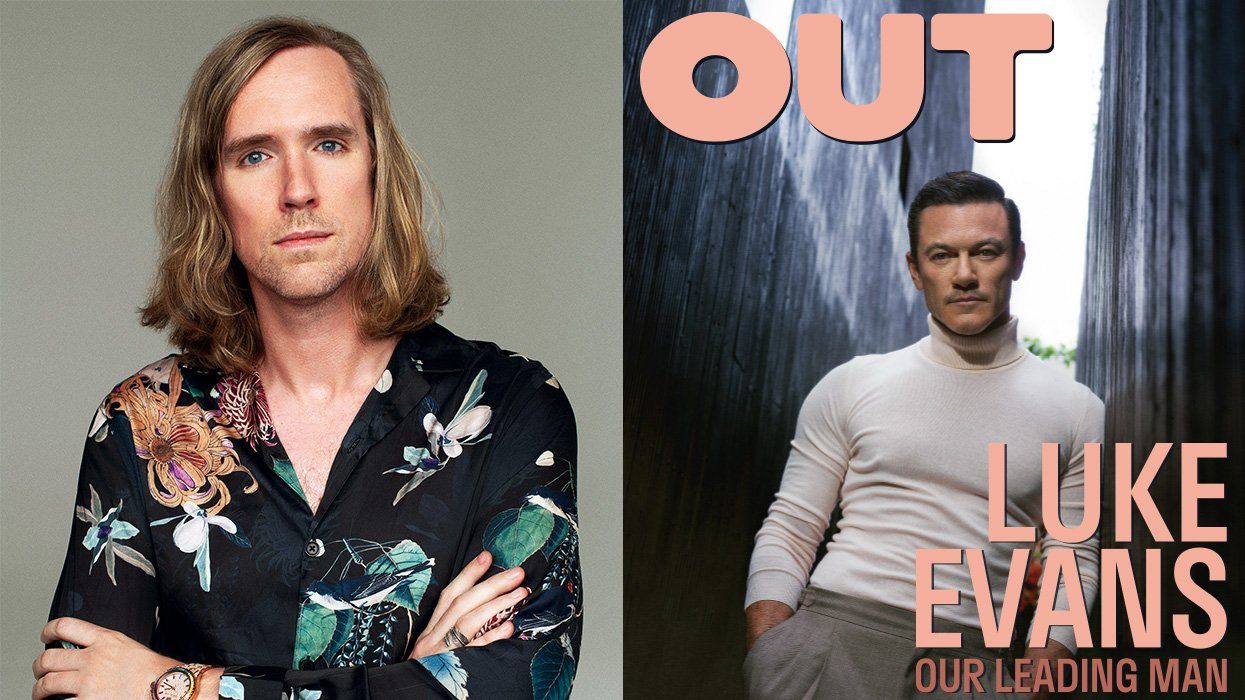

Out magazine and I both turned 30 this year (editor's note: the anniversary edition is next issue). My birthday was on March 7. In that short life, I grew into a writer and sex pig, while Out published the work of such queer luminaries as Edmund White, Bret Easton Ellis, and Dustin Lance Black. I knew years ago -- before I wrote for it -- that the magazine and I were the same age. We both marked the major events of our time: I in my small, private ways and Out with glossy spreads and celebrity interviews. I had just finished high school when "Don't ask, don't tell" was repealed and graduated college when the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. The magazine shaped these events in the queer consciousness. And these events, in turn, shaped me.

Half my life ago, I was a closeted kid sheltered in a religious, conservative family. My parents -- who barred me from listening to non-Christian music and promised damnation for homos -- left me alone in Barnes & Noble for hours while they took my sister shopping, perhaps thinking I couldn't get into much trouble in a bookstore. My parents are not literary people and had no idea how dangerous bookstores are to the fervent. They might as well have dropped me off at the gates of hell and told me not to touch anything.

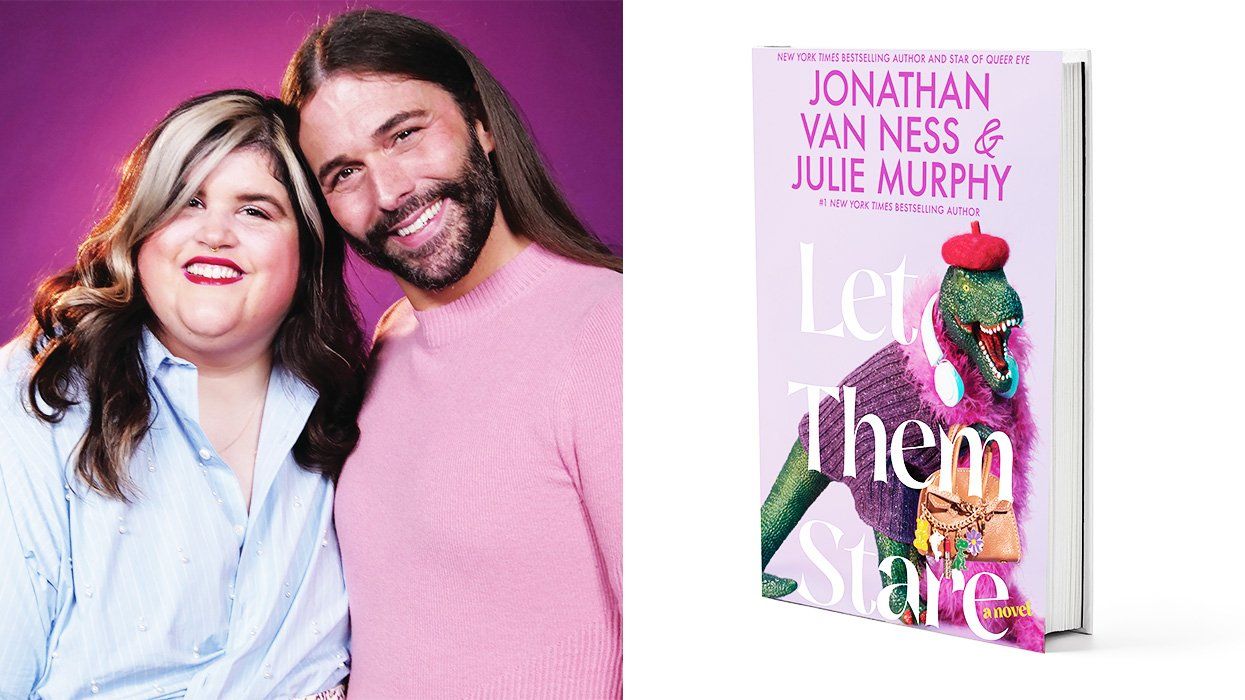

First I found a book of grotesque male nudes (Rare Flesh by David E. Armstrong and Clive Barker), then Unzipped, a gay porn rag -- one of many that are now sadly out of print -- on the magazine shelves. Next to it were Out and The Advocate.

Finding porn is one thing, but finding evidence of a culture beyond my parents' farm -- one of acceptance and freedom -- is quite another. Out was my first sign that there were more of us and that we were doing OK. At the time, my desires terrified me. Years later, after fights with my parents and messy college sex, I would write about those desires in the very publications I first stumbled across.

And now: 30. I have found and lost love a few times. I'm good at sex now -- I enter my third decade knowing what I like and how I like it. It would be nice to give the kids some advice, but advice would fall on deaf ears: You have to learn the things yourself, and advice is just a grown-up's silly effort to weave their own life into meaning.

It would be nice to make some profound statements on wisdom, beauty, confidence, or self-actualization -- things I'm still chasing -- and assure younger ones that life gets easier, but I'm not sure I can. I don't think life gets easier, but it does get better. I am more fortified against life's assailments than at 20, but of course, the assailments change. I have more time with my parents behind me than ahead of me. I've lost friends to cancer and overdose. And can you believe it: even my own body is mortal. These new aches and pains remind me of that.

But if you're 15 on the edge of 16, or 19 on the edge of your 20s, take heart. Stay. See what you grow into. My list of hurts has grown, but my list of loves has grown much more. I am able now to recognize good love, how it looks under strain, how it grows over time. If I could sit down with that little guy covered in acne who believed beyond a doubt that no one beautiful would love him, I would hardly be able to tell him how many people would pass through his life, people who would save and heal him in every way. Sweet boy, I am so proud of you.

Yes, there are odd parts of growing older. Gays half-seriously say I'm a "daddy" now. There's an odd sexual expectation of aging in our community that needs addressing -- the assumption that a queer man switches sex roles to become a top for younger men. This smacks of the same nonsense shown when someone complains of more bottoms than tops in an area (false, and a false binary to boot). I may no longer read as a "boy" in the crowd, but I can out-bottom the kids 10 to 1, and I intend to keep at it. Someday -- in a few years, I imagine -- I'll have flecks of gray in my hair and beard, and I'll still be getting jackhammered in a dark corner somewhere. Old pros do it best.

When Out and I were born, HIV-positive people took AZT cocktails with harsh side effects. 1995 saw the first of many better drugs. When I came along at 21 with a positive HIV test, I was given a mostly harmless single-pill regimen, and the meds have only improved since then. Those who tested positive when I did are the last generation to experience gay life before PrEP. We remember how brutal dating was then, how much the stigma of HIV impacted who we told and how. For two years, I was immediately blocked online (and on apps) whenever I told someone my status. I missed the boat on PrEP, but it nevertheless changed the landscape by making others less afraid. What a journey we've been on.

I am grateful for so much, for all my teachers and guides, but above all else, I am grateful most for simply being out -- for having the courage to do so and, later, the support and love to stay out, to live without compromise or apology. Being one of us has been the greatest gift and honor of my life.

Age really is just a number. It means nothing. It cannot speak to my dimensions or encapsulate my true growth, my true life. Tomorrow I will wake up, put on my daddy shoes, and hit the ground running.

Alexander Cheves is a writer, sex educator, and author of My Love Is a Beast: Confessions, from Unbound Edition Press. @badalexcheves