It is a fact of queer life: Your favorite gay bar, the one where you found your tribe for the first time, will someday close. Neighborhoods are gentrifying, nightlife is changing, and the Gay Bar — home — feels increasingly like a relic from when cities were cheap, dirty, and wild. I posit — for the first time in my writing career — that maybe this is OK, mostly because of some recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Last November, the CDC released an alarming report. In recent years, “excessive drinking” accounted for one in five deaths among Americans ages 20 to 49. That’s a lot of people. Most of my friends fall in that range. Following COVID-19, another report from the CDC showed equally grim numbers: In 2020, over 93,000 Americans died from overdose, the highest number ever recorded in a 12-month period and a 30 percent increase from the year before. Those were 93,000 friends.

Data on those who identify as LGBTQ+ relies on self-identifying, but most available data shows that we struggle with substances — drugs and alcohol — at higher rates and with worse outcomes than our hetero, cisgender peers. In 2020, research from Oxford University showed that all subgroups of queer — from bisexual women to transgender folks — have high rates of alcohol abuse disorder.

All that rings sadly true. Familiar, even. I’ve heard it in many variations: Gays have a drug problem. I lived it. I became a gay trope: the slutty sex worker with a drug history who ages a bit before doling out sage advice to young sprites. Gay films have endless versions of me, a tired queen droning on with war stories because, thank God, they survived.

But I did. Others did not. We drank heavily, used the same meth, went to the same parties, and fucked the same people or the same kinds of people. I did not lose friends to AIDS, as queer generations before me did, but I have lost them to a queer drug culture that existed before, during, and after AIDS — and exists today. Strides have been made by countless nonprofit agencies and organizations — like GMHC in New York and the Los Angeles LGBT Center — to provide counseling, 12-step groups, harm reduction, and so on. But still, our queer battle with consumption feels like an ongoing motif, a song on a loop.

I asked Andrew G. Marshall, a London-based therapist and author, the obvious question: Why?

Marshall, who is gay, says the issue is twofold. “Most of us were told from a young age that what we do is wrong, dirty, and disgusting, and there’s a lot of shaming,” he says. “Alcohol and drugs help facilitate sex in the gay world and make it easier. They quiet down the fears of not being good enough, not having the right body, not fitting in. These fears are quieted in a way that people who haven’t received that amount of shame don’t need.”

The second problem, he says, is that queer folks tend to come of age in bars and clubs, where drugs and alcohol are part of the experience of growing up. This is as true for me as for countless others. I found my people in a gay bar, met my first sex work client on a barstool, and got stuck in messy drugs for a bit. In the thick of those drugs — when I was steeped in drug overuse if not yet abuse — I got help from a harm-reduction therapist who worked at a nonprofit run by queer people for queer people. Just as LGBTQ+ people brought me to my adult life and showed me who I am via drag shows and party tickets, they also sent me a lifeline out of the pit before things got scary. Other queer men I loved were not so lucky.

Some might not have had any success from my harm-reduction approach. They might have needed the stringent rules of abstinence and 12-step meetings to get back into life. Everyone struggling, even mildly, with substances should explore all options and try all approaches before giving up. I have my personal issues with abstinence and 12-step, but I accept that some of us need all-or-nothing and the ritual of the rooms in order to stay alive. Every queer person alive now who participates in nightlife or at least enjoys the occasional gay brunch has — thanks to sobriety or simply moderation — survived a culture that inextricably links our identities to something in a bottle or pipe. Our sex is bound to substances. As a sex writer and worker, I know how serious that is. Sex is self. If sex is only reachable via mind alteration, a human will get high to feel good. We feel we need it in order to live.

So, what can we do? I asked the therapist. “We should be offering courses and workshops on how to connect without drugs,” Marshall says. “Can you feel your desire without the drugs artificially doing it to you? The answer, of course, is: You can, but to do so, you need to be able to connect deeply with yourself, and that’s not something everybody can do easily.” A therapist helps. And, Marshall says, we should normalize these conversations. “They should be happening everywhere.”

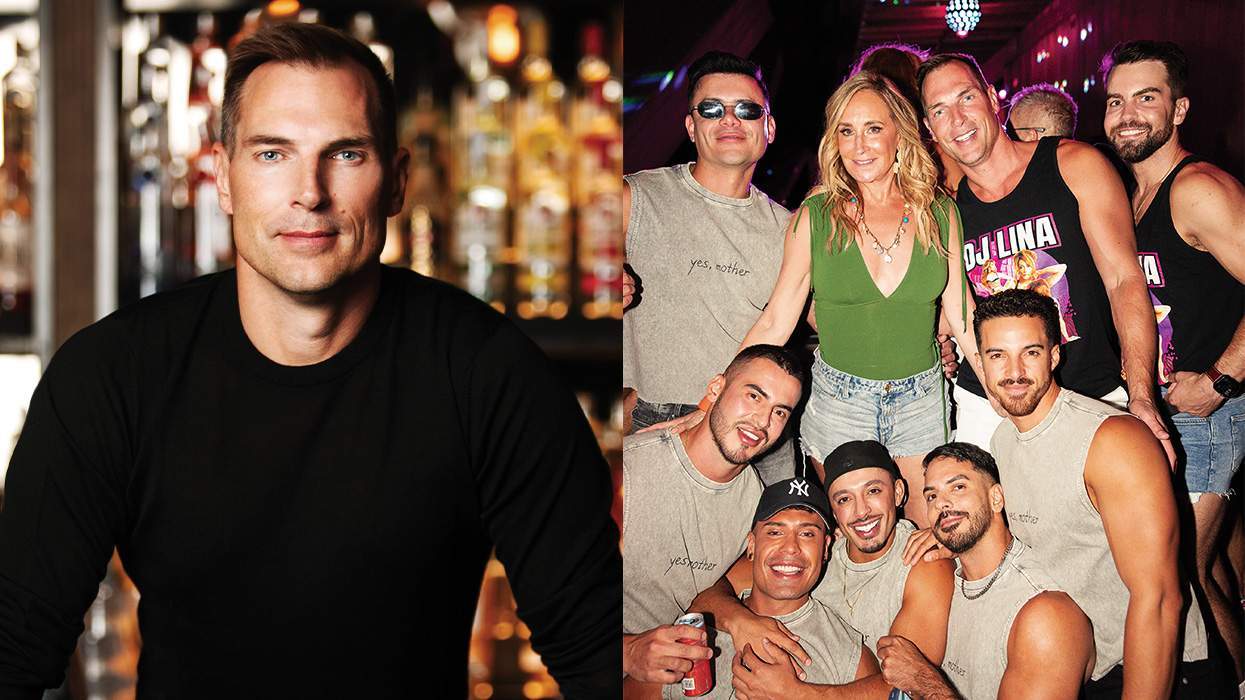

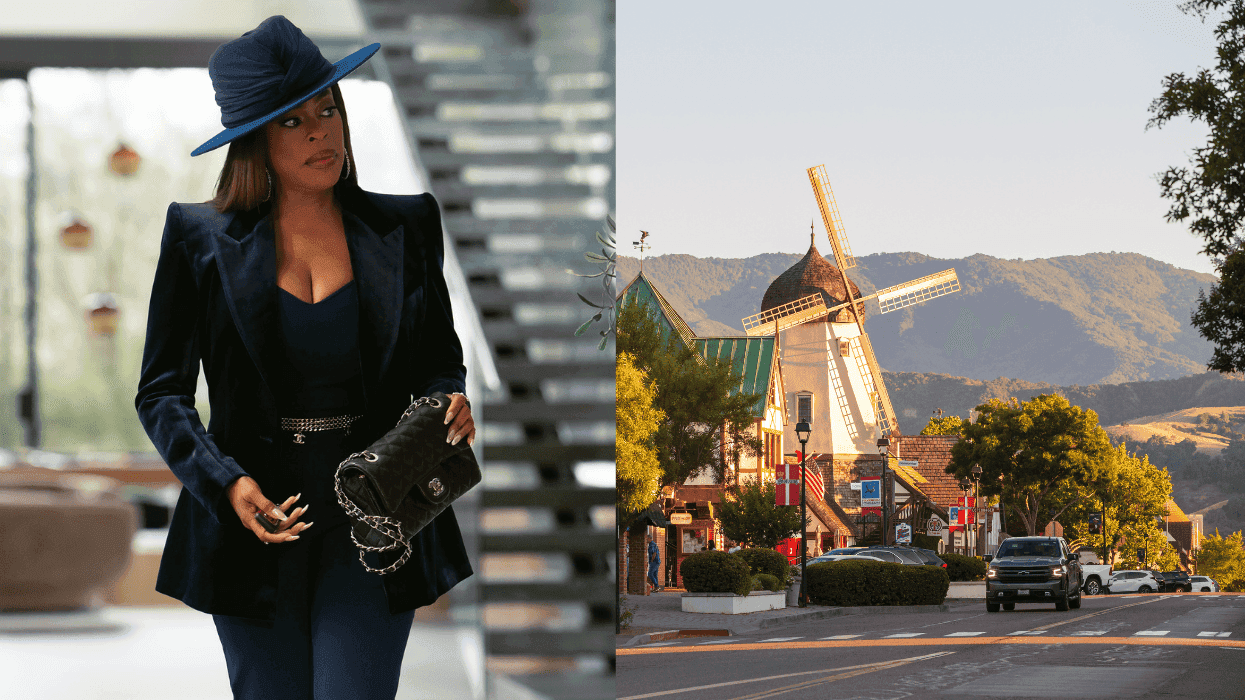

Increasingly, there are more spaces for queer folks to gather and have these dialogues than ever before — without booze present. L.A. has Cuties, a queer, sober hangout cafe run by Virginia Bauman and her business partner, Iris Bainum-Houle. New York has GMHC, Bluestockings Cooperative, and a monthly mixer hosted by Safer Spaces NYC. Across the United States, in big and small urban areas, queer-owned businesses have started to fill the growing gap between our community’s mental health and our long-standing tradition of gathering in the gay bar. In Berlin, where I live, there is Village, a multi-use space that holds dance classes, yoga, “heart circles,” meditations, and other events that build the social networks that once formed on barstools and in backrooms. While sex-positive, Village is not a sex club and offers a sanctuary for those who might not want to be touched or flirted with too heavily. And it’s dry — always.

For better and worse, queer culture has shifted out of the bar. We now have sports teams and parent groups. One hopes we can move the culture for our trans brothers and sisters as drastically as we have done for cis gays and lesbians.

Making space matters, but more than that, we must talk more about shame. “As a community, we’ve tried to replace shame with pride,” Marshall says. “We think if we’re proud, we can drown out those earlier messages. But that’s not possible. We must listen to shame rather than try to escape it. When we listen to it, talk about it, and hear other people’s shame, it begins to dissolve. Shame disappears in the light of attention.”

I still love — and work in — nightlife. Gay nightlife will never die. But it will change. It has evolved into queer. It will evolve again. Gay men tend to get nostalgic about the past — about lost bars, aging divas, and music from our youth — but it is important to cherish what was while also letting the more harmful parts of our culture go, even when they were sometimes wonderful too. Love of culture often butts up against the painful truth that culture must change and that this change is needed. Every queer generation — especially those that did not call themselves “queer” — has struggled with this. Every future one will. But change is inevitable, and sometimes it’s for the better.

To leave the Gay Bar is not to say it didn’t matter, and all this is certainly not to isolate or attack the sexy, boozy, cruisy gathering spaces still open and running, like the ones I visit and love. We just need more sober spaces too so that the rest of us — the ones we need to be taking care of, who often struggle to ask for help, who need friends right now — can feel like they belong. Because they do.

Alexander Cheves is a writer, sex educator, and author of My Love Is a Beast: Confessions from Unbound Edition Press. @badalexcheves

This article is part of the Out March/April issue, out on newsstands April 4. Support queer media and subscribe -- or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.

I watched the Kid Rock Turning Point USA halftime show so you don't have to

Opinion: "I have no problem with lip syncing, but you'd think the side that hates drag queens so much would have a little more shame about it," writes Ryan Adamczeski.