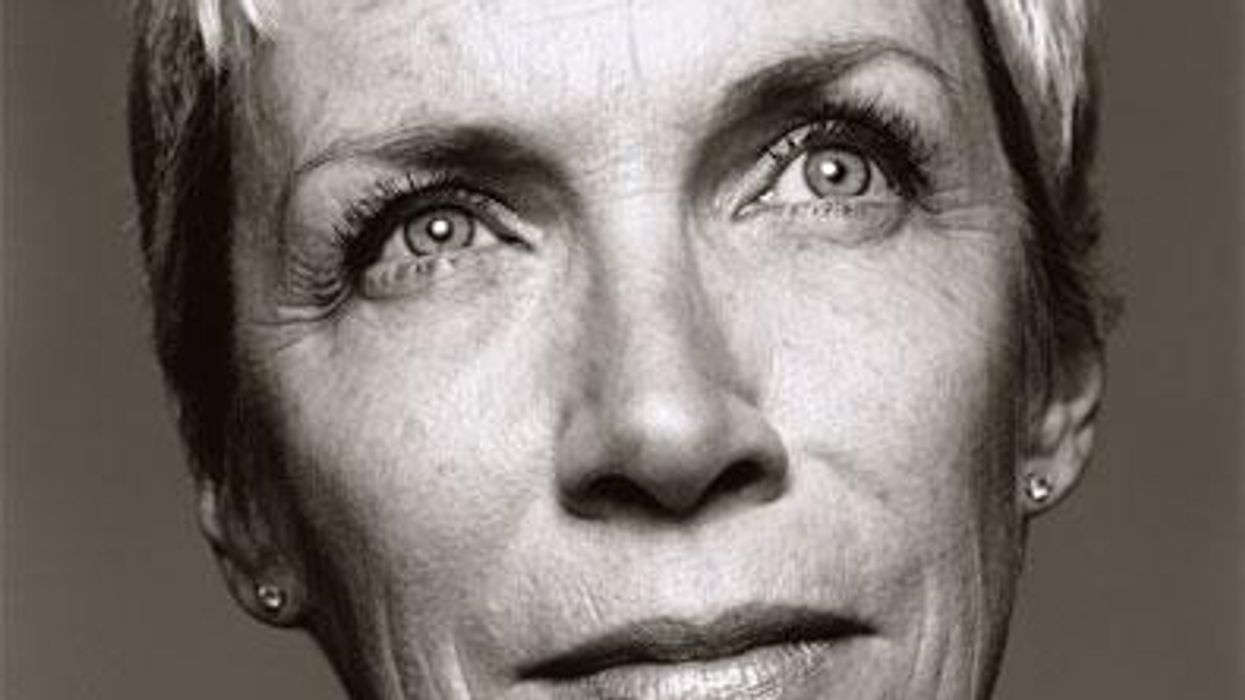

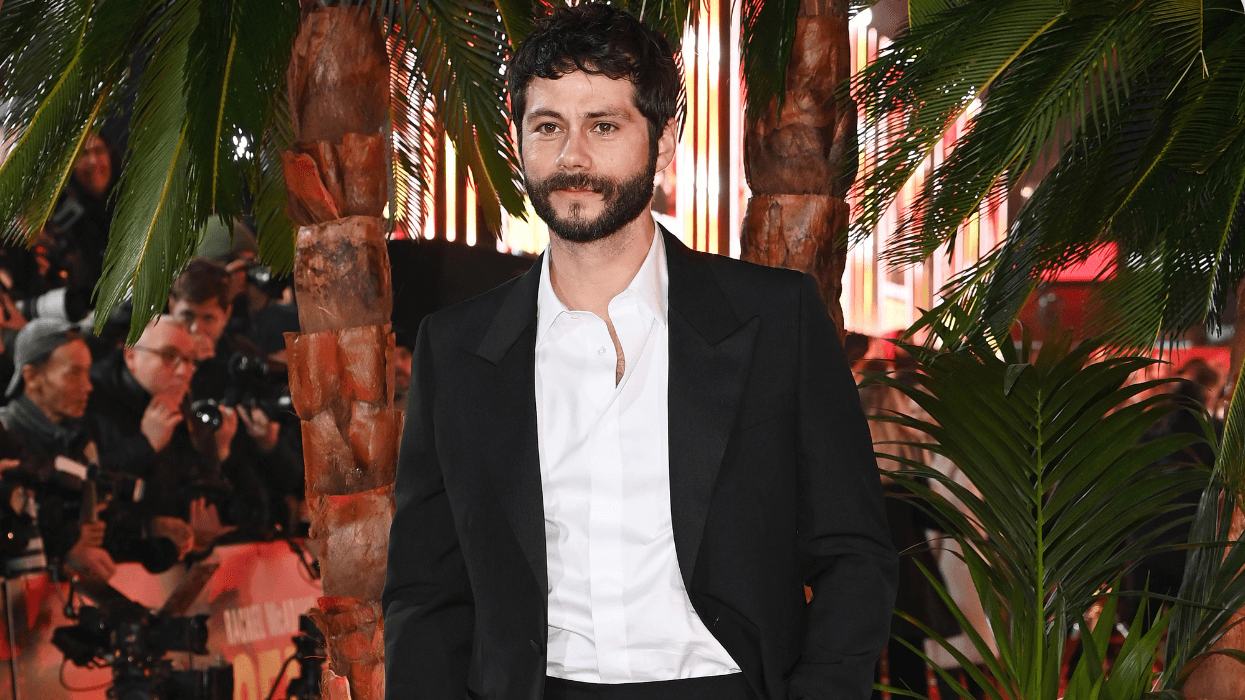

Photography by David Bailey

Writing in The New York Times in 1984, the critic Stephen Holden sought to draw a distinction between the Eurythmics and the rest of what he called the 'British synthesizer-pop movement,' including Duran Duran, Culture Club, and the Thompson Twins, then making inroads into the American charts. 'Miss Lennox,' he wrote, 'possesses one of the loveliest voices in English pop. She skillfully projects her husky folkish alto into piercing jazzy wails.'

Last November -- a quarter century, 10 albums, two husbands, two daughters, and much heartache later -- Miss Lennox walked onto the stage of the Nokia Theatre in Los Angeles and held the audience of the American Music Awards rapt with a performance of 'Why' -- as beautiful a song as anyone has ever written. Watching her at the center of that vast and empty stage, sans orchestra, sans backup singers, sans the smoke and mirrors that had supported the evening's other headliners -- flames for the Pussycat Dolls, a storm of butterfly-shaped confetti for Coldplay -- it was impossible to separate the naked vulnerability of the lyrics from the life of the woman singing them. Hurt and loss and disappointment were contained there -- and catharsis too. The teenage girls might have come to see the Jonas Brothers and Miley Cyrus, but it was the then'53-year-old Annie Lennox who received the longest ovation of the night.

'I'm always trying to find a fresh way to say the same thing, I guess -- the same thing being a sort of language of the heart,' Lennox muses, a day before her appearance at the American Music Awards. 'There's always been an element of the tortured soul -- I mean there has to be, you know? It's kind of this existential angst that we all feel at different levels, whether we realize it or not.'

Holden was right, of course, not only in recognizing Lennox's talent but for drawing attention to the central tension at the heart of the Eurythmics. From the beginning they managed to be simultaneously cool and soulful, ironic and earnest. Early stars of MTV, they might have been swallowed up by the scale of their own spectacle if not for the intimacy of Lennox's lyrics. It's not simply the insistent hooks and muscular melodies that give songs such as 'Love Is a Stranger,' 'Here Comes the Rain Again,' and 'Sweet Dreams' their enduring power, it's the conviction with which Lennox sings them. Like Dusty Springfield's, her songs often have the quality of an exorcism, endlessly circling back to the twin themes of love -- 'It's noble and it's brutal, it distorts and deranges' -- and loss -- 'It touches and it teases as you stumble in the debris.' As a motif it's proved remarkably fruitful over her long career.

It's a bright, sunny afternoon in November, and we're sitting in the garden of the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles. Lennox is jaunty and expansive, dressed in a light embroidered blouse and very poised, upright, as if she'd been taught to walk with a book on her head. One of her great paradoxes is a faintly prim and reserved mien that seems at odds with the transgressive, cross-dressing persona she projected in such early Eurythmics videos as 'Love Is a Stranger' -- yanked off the air during transmission on the fledgling MTV by executives who thought they were watching a transvestite -- and 'Who's That Girl,' which ends with the feminine Lennox kissing her masculine alter ego. But unlike, say, Madonna's provocations, which were designed to accentuate her sexuality, Lennox's cropped tangerine hair and men's suits were aimed squarely at subverting the lazy signifiers of pop. 'It's about how malleable the whole idea of self really is, that if I put on a wig and a bit of stubble and a suit, I'm perceived as a man,' she says. 'The playing with gender was all about that: 'You cannot define me through my sex -- I'm more malleable than that.' But when you spell it out, people think you're barking mad.'

At the same time, you wonder if the multiple personalities and lavish costumes evolved as a coping mechanism for Lennox's crippling insecurities and loneliness, an elaborate variation of dress-up to mask her sense of alienation. 'I was always trying to escape from restraint,' she tells me at one point, a theme she frequently cycles back to. 'I think that's why I've taken on these characters. I know I am one person -- this is my body, and it's the one that will take me right to the end -- but we're all very typecast in our particular personas, and it's quite limiting.'

This might sound familiar, since it mirrors the experience of many gay men who, like Lennox, learn to neutralize their sense of exclusion by reinventing themselves -- a subtle kind of role-play that compensates for insecurity. 'Although I'm heterosexual, I've always identified with that story of coming out, because part of my process was coming out to myself,' Lennox says. 'It's hard to explain, but it was about learning that I was an artist and that it was fine to be creative. I'd always been threatened, like 'If you don't stick at school, you'll end up in a factory,' and it was very fear-based -- a feeling that maybe there was something untoward about you, something not quite right. So I never felt I fitted in anywhere, and I still don't. There's no complaint, but it's part of the story -- always looking for the tribe, never finding it.'

Though not miserable, Lennox's working-class childhood in the Scottish city of Aberdeen was not always happy and might have been worse but for a piano her parents bought her at age 3. Not a proper, grown-up piano, but a plinky-plonky toy piano on which she was very quickly picking out tunes. 'I wasn't Mozart. I wasn't a genius, but there was a propensity there,' she says. 'And there was also singing -- singing, singing, always singing.' At night she used to sing herself to sleep. 'I was just a sponge for every piece of music,' she recalls. 'I don't remember a time when music wasn't there.' (It's not surprising, somehow, to discover that among the first records Lennox ever bought was the soundtrack to Mary Poppins; like that flying nanny, she embodies a peculiar combination of propriety and eccentricity.)

By 11, Lennox was playing the flute too, an old one that she found at school, held together with elastic bands (she called it Flora). The first time she played it, she hyperventilated so much she threw up all over the floor and had to be sent home. Although she hit adolescence in the so-called Swinging '60s, apparently no one thought to inform Aberdeen. At the Beach Ballroom on the seafront, where local youths gathered on Fridays, you were more likely to hear Motown and Stax records than the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, an influence that would percolate through her career. On the whole, though, it was a time of depression and angst, exacerbated by the sense that 'I wasn't good enough, I wasn't bright enough, I wasn't clever enough.' In that stern, unyielding city, even Lennox's music teacher inflated her insecurities with heavy-handed sarcasm. 'It was her way of motivating me,' says Lennox. 'But to tell a kid of 9 that they're going to be the laughingstock of Aberdeen is not great.' Surely there was one teacher she formed a bond with? Lennox shakes her head: 'Didn't find that one.'

Lennox's sense of not fitting in, of being, as she puts it, 'a round peg in a square hole,' has stubbornly persisted. She says she never felt understood by anyone until she met Dave Stewart when she was waitressing at a health food restaurant in London -- around the time she was discovering her own voice through the records of Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell. She was 22 and floundering after dropping out of the Royal Academy of Music. He was a witty, brazen bullshitter who stowed away in the back of Amazing Blondel's van at 15 (then hung with them for six whole weeks), started and dropped several bands, and spent a year on acid inventing his own language. The day he met Annie he proposed to her. Although they never married, their relationship, its complexities and agonies, would become the creative source of one of the most iconic rock bands of the '80s.

'We were nuts,' Lennox says of the intense work ethic that kept the duo touring and recording almost constantly through the '80s. While their first venture, the post-punk outfit the Tourists, had only minor success (with a cover version of Dusty Springfield's 'I Only Want to Be With You' -- their first taste of being labeled 'sellouts,' at a time when such accusations stung), Stewart's driving ambition and self-confidence persuaded Lennox to persevere as they tried again, this time as the Eurythmics. It wasn't easy. Their first album, 1981's In the Garden, was a flop, and growing tensions between Lennox and Stewart almost brought the project to a premature end. The day they recorded 'Sweet Dreams,' Lennox had resolved to return home to Scotland, but something about the tune Stewart was banging out on the synth drew her from her shell. 'I was so despairing,' she says. 'But what I've noticed is that often there'll be a moment, a real down, and then something comes along and the energy goes right up.'

The song that made them international superstars was recorded in a single take, Lennox improvising most of the lyrics on the spot. They used a TEAC 8-track in an attic Stewart had converted for the purpose, without any of the fixtures of professional studios. That chiming sound as Lennox sings 'Hold your head up' is nothing more than Stewart tapping on milk bottles, filled to various levels with water. 'My relationship with Dave was quite an extraordinary thing,' says Lennox. 'It has so many chapters, you know. And then there was a point where I just desperately wanted to figure out who I was by myself, 'cause we were always, like, joined at the hip.'

Over the course of eight albums recorded in as many years, the synths and drum machines gradually receded, replaced by more traditional rock arrangements and ballads. 'Angel,' a lament for Lennox's stillborn son on the duo's last proper album (another, in 1999, is best forgotten) foreshadowed her multiplatinum solo debut, Diva, and if she recorded nothing else, it would be enough. Without sacrificing the elegant gloss of her Eurythmics-era songs, Lennox nevertheless seemed to find her authentic voice in these 11 tracks of aching disaffection and redemption. If the album's hit single, 'Why,' has become her standard-bearer, it's in the fragile album closers, 'Stay by Me' and 'The Gift,' that you hear Lennox making peace with herself. 'My musical creative journey is very much connected to my inner world and an aspiration to create something that could express it articulately and beautifully and with power,' she says, adding that if listeners recognize themselves in her songs, she considers her job well done. 'That's what music is, a sublime communication that is beyond even the words we use.'

Although it received some dismissive reviews from the perennially miserable British music press, the album's stature seems only to have improved with age, perhaps because its particular brand of soul-pop has weathered better than either grunge or Britpop, so dominant at the time. As with Amy Winehouse and Adele, her great instrument is her voice; but where Winehouse affectingly slurs and mumbles her words, Lennox's locution is pristine (Mary Poppins again), her words less idiomatic, her lyrics more formally constructed. 'I started off writing poetry when I was about 12,' she recalls. 'I didn't write great poetry, but what I did discover was this incredible thrill of expressing myself in a word or a combination of words in a poetic phrase.' If that brand of literariness, never particularly fashionable in the first place, and the fact that she eschews the public meltdown for a more private kind of pain, have served to make Lennox seem faintly passe, she welcomes the creative freedom it gives her. 'I've had my taste of living in the spotlight, and I know I don't want it. I'm a musician. I'm a communicator, and the last, last, last, last thing I want to be is this word -- celebrity! What part does that play in my life? It's so diminishing. People will sell their dogs, their kids, their Jacuzzis -- they'll do anything for this allure of being a celebrity.'

Lennox's solo work since Diva (three more albums in 16 years) has been more introspective than her Eurythmics material, as if, left to herself, she can't help but drift into a kind of solipsism of the heart. A sample of song titles from her last two albums -- 'The Hurting Time,' 'Bitter Pill,' 'Loneliness,' 'The Saddest Song I've Got,' 'Twisted,' 'Dark Road,' 'Lost,' and 'Through the Glass Darkly' -- tell their own story, although a cover of Ash's 'Shining Light,' on the upcoming The Annie Lennox Collection is unusually buoyant, perhaps because she didn't write it. 'To say I'm a drama queen would be an understatement,' says Lennox. 'But I think music, and music making, has validated my demons, in a sense, just by expressing them.'

Of the 12 'collected' songs on The Annie Lennox Collection a full half are lifted from Diva, if you include the welcome appearance of 'Love Song for a Vampire,' recorded for the Francis Ford Coppola movie Bram Stoker's Dracula and released as a double A side with 'Little Bird.' (The two new songs bring the number of tracks to 14.) Sadly overlooked is Lennox's cover of Cole Porter's 'Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye,' recorded for the 1990 AIDS benefit album Red Hot + Blue, a quietly devastating interpretation hailed by The New Yorker as 'one of the best recordings of a Porter song ever made.' Like 'Angel,' it gains power from Lennox's sense of bereavement, made all the more poignant by the accompanying video: old cine footage of a young Derek Jarman, the cult British director who later died of AIDS, frolicking on the beach with his sister. 'He was supposed to direct the video for Red Hot + Blue but got quite ill around the time,' recalls Lennox. 'I went to visit him in the hospital, and he was so sweet and so charming, just sitting up in bed in his lovely silk paisley dressing gown. He was the first person I met who was actually HIV-positive.'

Jarman recovered long enough to make several more movies, including his great allegory on gay oppression, Edward II, in which Lennox sings 'Ev'ry Time'' as the young king and his lover dance one last time. It's an electrifying moment and one that helps advertise Lennox's great screen presence. Indeed, looking back at the videos for the Eurythmics as well as those for Diva (for which director Sophie Muller won a Grammy), it's striking to realize how cinematic they are, with Lennox acting up a storm -- costumes, wigs, and all. (The French Restoration'inspired video for 'Walking on Broken Glass' even included cameos by John Malkovich and House's Hugh Laurie.) 'Often there's a lot of self-mockery in what I'm doing,' she says. 'It's not always obvious, but I do have a sense of humor.' Although she has only made rare forays into movies (including a Robert Altman''directed version of Harold Pinter's The Room), she thinks she might enjoy doing 'a really good character part, just for the fun of it, nothing else.'

Increasingly, she seems to have turned much of her energy toward her human rights work, very publicly in the case of Nelson Mandela's 46664 campaign against AIDS in Africa, and again more recently during Israel's bombardment of Gaza in January, when she used her celebrity for a string of interviews in which she condemned the deaths of civilians. 'People can call me naive and idealistic, but those weapons don't have to be used, those young children don't have to die,' she says. 'I just think warfare is incredibly primitive.'

Last year, after 30 years under one record contract or another, Lennox allowed her agreement with Sony BMG to expire, content for now to communicate to her audience via her MySpace blog and by posting photos on her House of Me website (a slightly goofy Clue-style series of rooms, in which users can explore aspects of Lennox's life and interests). She says she was always shy onstage, unsure what to say, and finds that words come more naturally on her blog. 'I do know that the website is the real vehicle of communication for me. And I can make anything I want, and I love that. It's so much more satisfying in a way than just making songs.'

She has learned, she says, to be more pragmatic, but not thick-skinned -- 'Because if you get too thick-skinned you get too desensitized and jaded, and I don't want to be jaded.' And if her battles aren't entirely over -- even now she will find herself, sometimes, lost in her own head 'looking at the sky in Aberdeen, and the grayness of it, and the sleet and the buildings, and the certain color of light' -- she has at least worked out a purpose for her life.

'Tell it like it is, tell it like it is,' she sings, a personal admonition and a mantra, in the closing seconds of 'The Hurting Time' on her album Bare. You could say she's been telling it like it is from the very beginning. It's unlikely that she'll be done any time soon.

The Annie Lennox Collection is available now.

Also be sure to catch Annie Lennox's on A&E's Private Sessions where the singer will discuss her career and perform some of her most beloved hits. The show premieres on Sunday, March 8 @ 9 AM ET/PT.