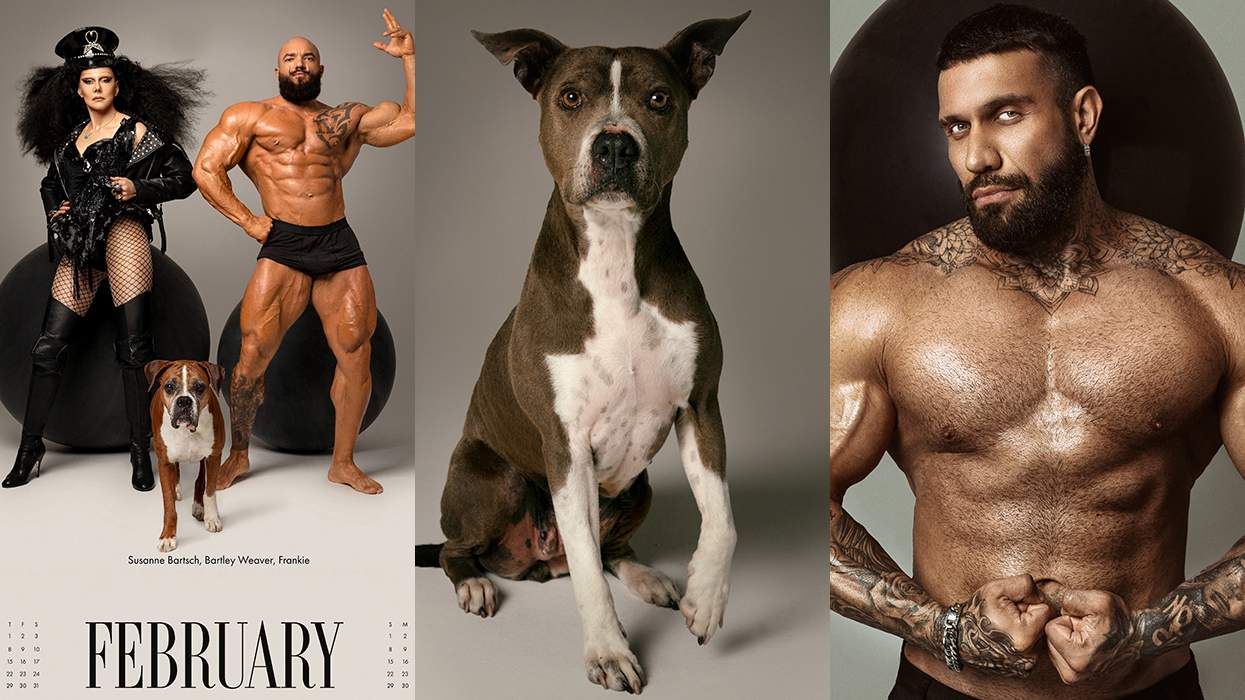

Art has always played an integral part in the AIDS epidemic. Gran Fury, the ACT UP-affiliated collective, created the Silence = Death poster. Visual imagery in pamphlets fought miseducation about the virus and spread safe-sex messaging throughout queer communities. And while some art was meant for the street, just as much art around AIDS came from the studio, exploring the relationship between the activist, the virus, and the world around them.

Devin Morris, a Brooklyn-based studio artist, explores his own diagnosis through his work. Morris, who tells Out he believes "every object has a heart," uses scavenged objects like drapery and furniture to construct elaborate, often monochromatic, spaces built of composite pieces that together make a new whole. He says part of his love for scavenging comes from his mother, who would stoop down to pick up flowers right from the soil as the two shared walks around his hometown of Baltimore.

Most of what ends up in Morris's works isn't purchased, it's scavenged. For him, any stroll down a Brooklyn street is an opportunity to make art. As he walks, he looks for anything (couches, lamps, and fabrics) he can use as a part of the elaborate spaces he creates and photographs.

Morris's childhood factors into his work both thematically and in execution. As a child, Legos were his favorite toy and he would use them to build dwellings out of cardboard and other found materials for his meticulously-coiffed Barbies. He attended a high school that specialized in engineering, training him to dismantle an object into its disparate parts.

Now, as a fully realized artist, Morris creates spaces. He dresses them in texture with found objects like drapes or curtains and bathes them in bold--often monochromatic--color schemes. There's a return to innocence in his work, something he contends was partially wrested from him after experiencing the death of his father in 2004.

Collecting objects and putting them together into a cohesive whole mirrors how Morris views the world: fractured and shattered--especially when it comes to his own identity. As a Black, queer person, he says that he thinks of his intersectional identity as an "abstract concept" that his art can hopefully embody. Bringing these separates pieces together then, is a way to celebrate each individual part while also putting them in dialogue with one another.

Morris got his start working in fashion as a buyer when he began to make collages: at first, just to make flyers for a social Sunday event he held first in Baltimore then in Brooklyn as a salon for artists and writers. His collages became a facet of his annual publication, 3 Dot Zine, which launched in 2014 and led to him applying for an artist residency. It was there that he first took the label "artist" and figured out that his work was inherently political.

"I was hyped up on this idea that all my issues were racial or dealing with a social issue," Morris says. "Once I freed myself of all those ideas, I began making my art more directly, like with a more direct relationship to creating an image."

For his work "4 Stages of Living Positively," Morris wanted to create an honest and vulnerable space to explore his own HIV diagnosis. He found the space in a barn in upstate New York, where he says a set of stairs gave him the feeling of vertical ascension. He decorated the stairs with several found lamps, a brown blanket, a wooden chair, and a venetian blind. In some shots, Morris stands behind the blinds.

"I felt a distinction between being positive and shrouding myself in the shame of it," Morris says. "There was such a fear of 'What happens if I say it?'" That fear, Morris says, has since subsided. Diagnosed in 2015, Morris was concerned when he came out to his family on World AIDS Day in 2018. "I was like, 'You cannot be devastated because it doesn't feel devastating.'" He adds, "I don't want shame and I don't want fear because I don't live in fear--and I led with that."

Morris's work has led to several shows and critical acclaim: in 2017, Time named him one of 12 Black photographers to follow. He's exhibited his work at New York City's La Mama gallery, the AC Institute, and the Minnesota Museum of American Art. He was most recently featured in an exhibition by the New Museum and the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall riots.

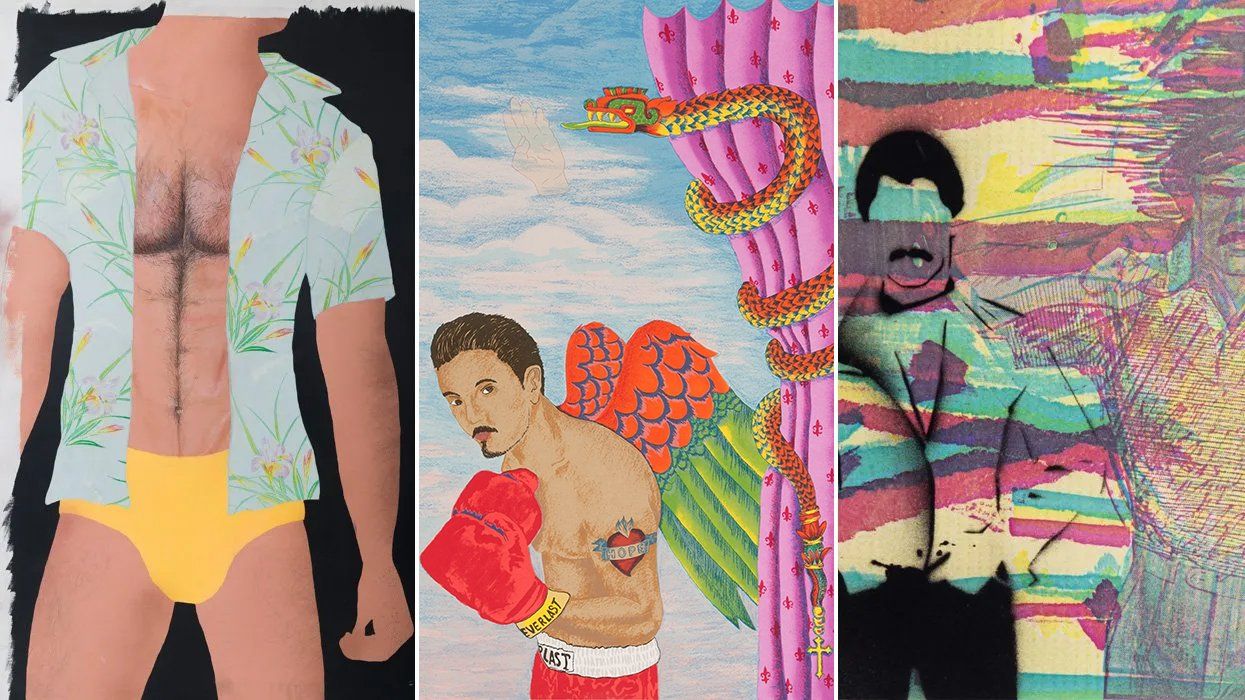

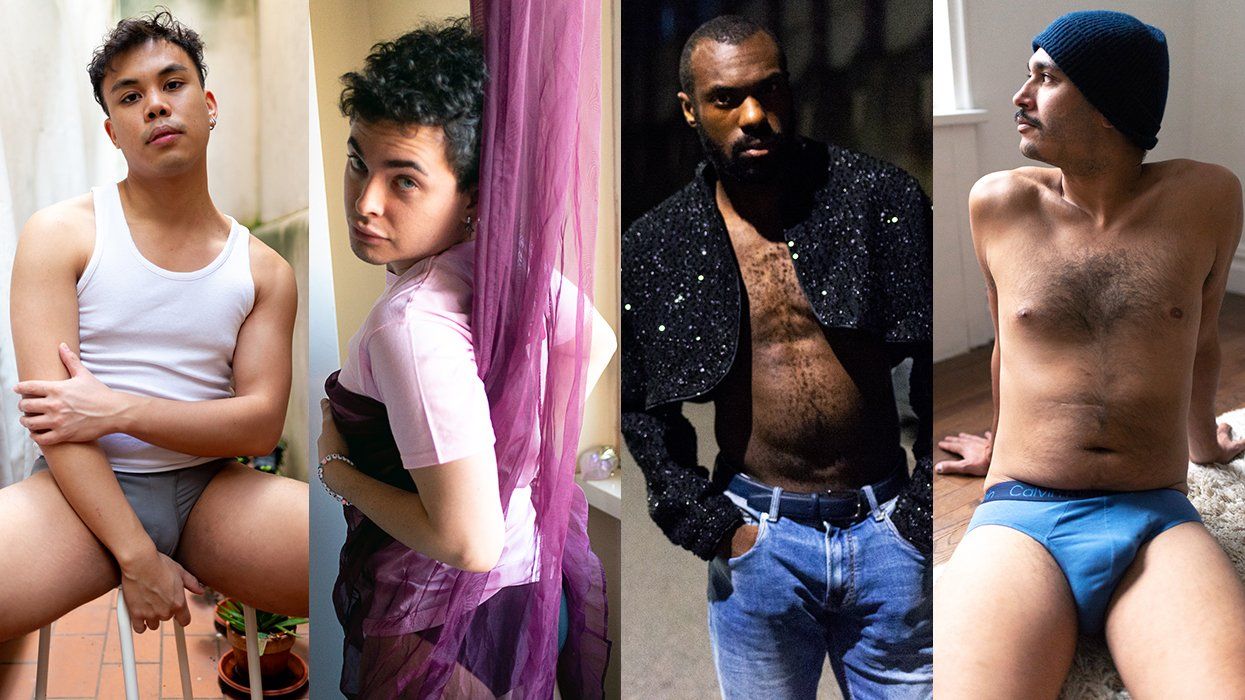

Though his star has risen, Morris does not always star in his own sets. Given his history in fashion, he loves to dress other people. Gender seems to play no role in what the men in Morris's work wear. His subjects sport floor-length floral pattern skirts, long royal capes, and fur coats. They often wear silky, flowing blouses. Morris says he puts men together in photos to change viewers' ideas of male interaction.

"I remember men and kindness and the men who I love the most were the kindest people, especially to me," he says. "I believe that men love each other, whether that be romantic or innocent."

In depicting these exchanges, he's fighting a society that refuses to acknowledge that these interactions exist. And just by making art, Morris continues a long legacy of artists using their work to explore life with HIV, while also making space--literally and figuratively-- to center Black gay men in the conversation.

This article appears in Out's May issue featuring artist Zanele Muholi and model Ruth Bell as cover stars. The issue is guest edited by Kimberly Drew. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio or (newly) Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here and click here to subscribe.