In drag, the ability to laugh at yourself is not only an advantage, it's a necessity--one of the weapons that gay people use to disarm aggression, fend off humiliation and honestly manage your own ego. This sensibility is what's missing from I, Tonya, the new mockumentary about the beleaguered Olympic figure skater Tonya Harding and her career-ending involvement with the 1994 attack on competitor Nancy Kerrigan--a real-life version of the movie Showgirls where the fight-for-your-life sensibility contributed to popularity among drag artists and its status as a camp classic.

Related | Call Me by Your Name's Sex Lives of the Rich and Immodest

Harding's not gay but her life story is poignantly queer: skating her way up from white working class anonymity to being recognized for her genuine talent and skill, then losing her career: through a combination of unfortunate choices, associating with a disreputable man and having the sheer bad luck of being on the wrong side of polite society.

This saga conforms to the ways that female celebrities become iconographic figures when gays can empathize with the female striver's hard-knock life and understand the necessity of laughing at yourself before others do as a way of survival.

This sensibility is leaching out of modern life, particularly in the safe-spaces culture that teaches women and gays to accept victim status; to "protest" rather than how to persevere. There's resentment and hostility hidden inside this pity and it comes out--shockingly--in I, Tonya when Harding is criticized by her envious, alcoholic mother (Alison Janney): "You skated like a graceless bulldyke!"

That homophobic insult betrays the film's many micro and macro-aggressions related to gender, race and class. It denies the strength of resilience--that quality that helped Harding to glide across the ice and perform her justly acclaimed triple axel, the athletic, balletic feat of lifting oneself up, rotating, shifting weight and then landing gracefully and firmly. That rarely achieved maneuver (named for Norwegian skater Axel Paulsen who originated it and mastered by few skaters of any sex) is a metaphor for strength, talent and ingenuity. The movie I, Tonya de-emphasizes these qualities through the way director Craig Gillespie and writer Steven Rogers choose to ridicule Harding and the people around her as white trash. The film's sarcasm insists on Harding's tragedy, encouraging viewers to laugh at her rather than feel for her.

Britney Spears fans will recognize the phenomenon. The same antagonism was unavoidable in the period when Britney became a media punching bag (leading to Chris Crocker's infamous, hilarious YouTube clip "Leave Britney Alone!"). I, Tonya might have been an acceptable, gay-friendly film, if Harding was given some of Britney's pluck or some of the sass that so vital to Elizabeth Berkley's Nomi in Showgirls.

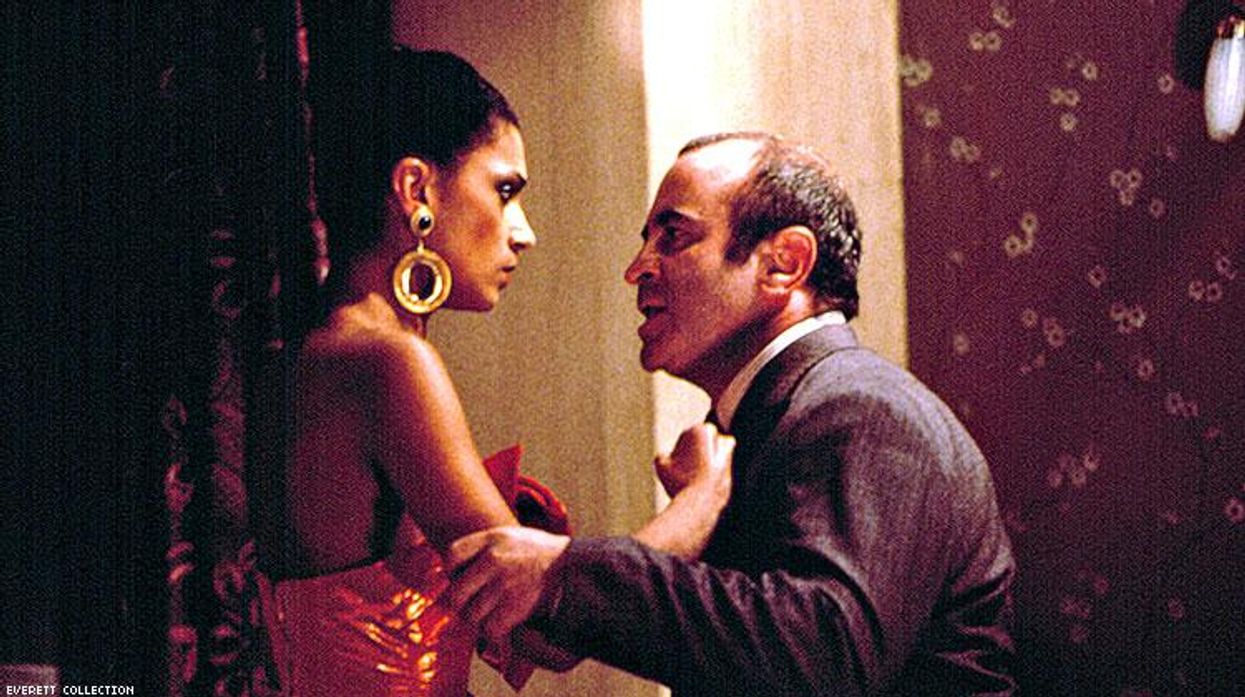

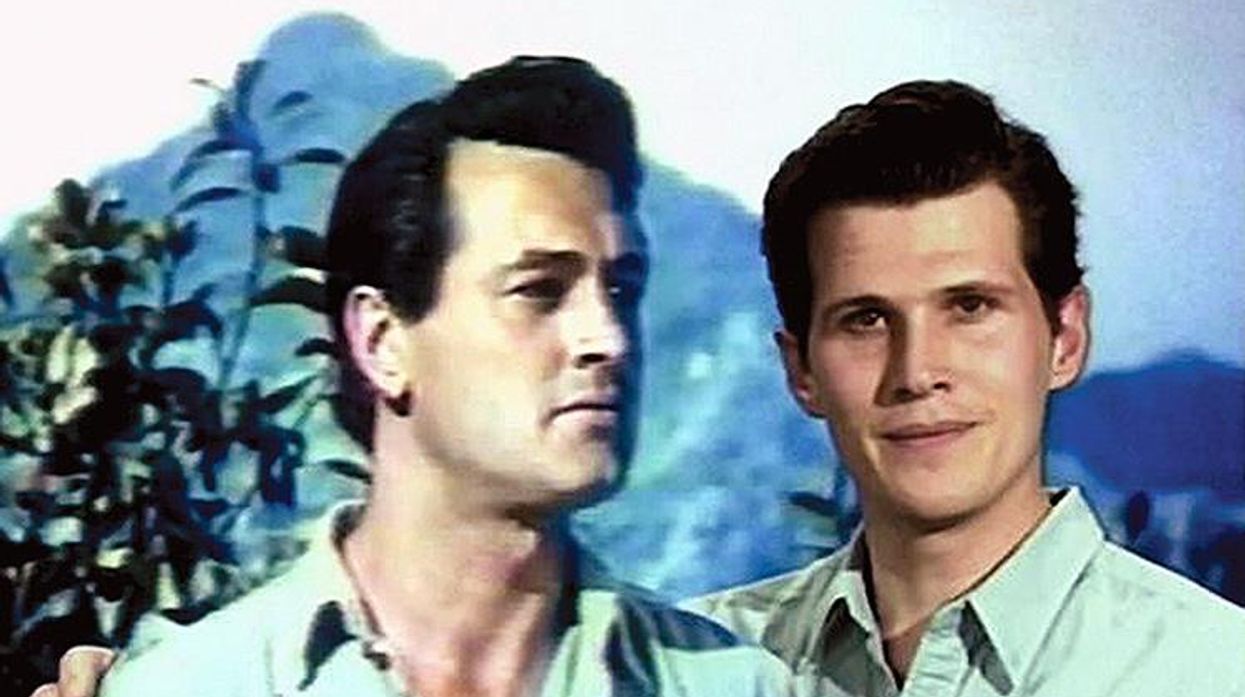

I, Tonya needs gay vitality and a strong gay sensibility. It's un-gay in the same way the sexual innuendoes in a film like Wonder Woman are un-hip. What goes wrong is apparent in casting Australian actress Margot Robbie who confuses this Oscar-bait role with Charlize Theron's stunt in Monster, especially in scenes where teenage Tonya gives in her adolescent horniness with douchey Jeff Gillooly (played by Sebastian Stan without the bromantic sexiness of his Bucky role in The Avengers).

Robbie is similarly robbed of her one chance at icon-status when Tonya defends herself with a baseball bat--a too-brief gesture that recalls Beyonce in the "Hold Up" music video but particularly Robbie's best film role as Harley Quinn in Suicide Squad. That, ponytailed, love-sick, versatile supervillainess has captured the imagination of more filmgoers than Wonder Woman (Harley Quinn clones are multitude at every Comic Con) and that gum-chewing impudence is what gay sensibility intuits even in Harding's hard luck story. (Robbie's expertly tooled sex kittenishness works best in the hiked-up skirt and schoolgirl tease of her homemade skating duds).

Instead, we get a maudlin scene of Harding facing her problems in a make-up mirror like some old lady Joan Crawford cliche. Her 40-miles-of-rough-road domestic abuse (by mom and husband) and courtroom trials are underscored with snarky pop music cues ("Devil Woman" and Fleetwood Mac's "The Chain") that don't work the way camp ought to. Every risible moment exposes the filmmaker's class, race and gender contempt--it's camp on ice and the farthest thing from the gay sensibility that contemporary Hollywood sorely lacks.