On one level Andre Techine's Being 17 is his sexiest movie because of the hormonal pulse it dramatizes between two French teenagers, Thomas (Corentin Fila) and Damien (Kacey Mottet Klein), high school outsiders who bully each other to cover-up for the attraction they feel. Then, on another level, Being 17 illustrates ethnic and class differences in the modern world through Thomas and Damien's uneasy romance.

Better than a Hollywood adolescent getting-laid comedy, or a socially-conscious message movie, Being 17 is so lively that watching its characters rushing through their encounters produces a rare sense of discovery. Thomas and Damien's yearnings, always eager and perplexed as they realize their own thoughts and feelings, gives Being 17 vivid, recognizable immediacy.

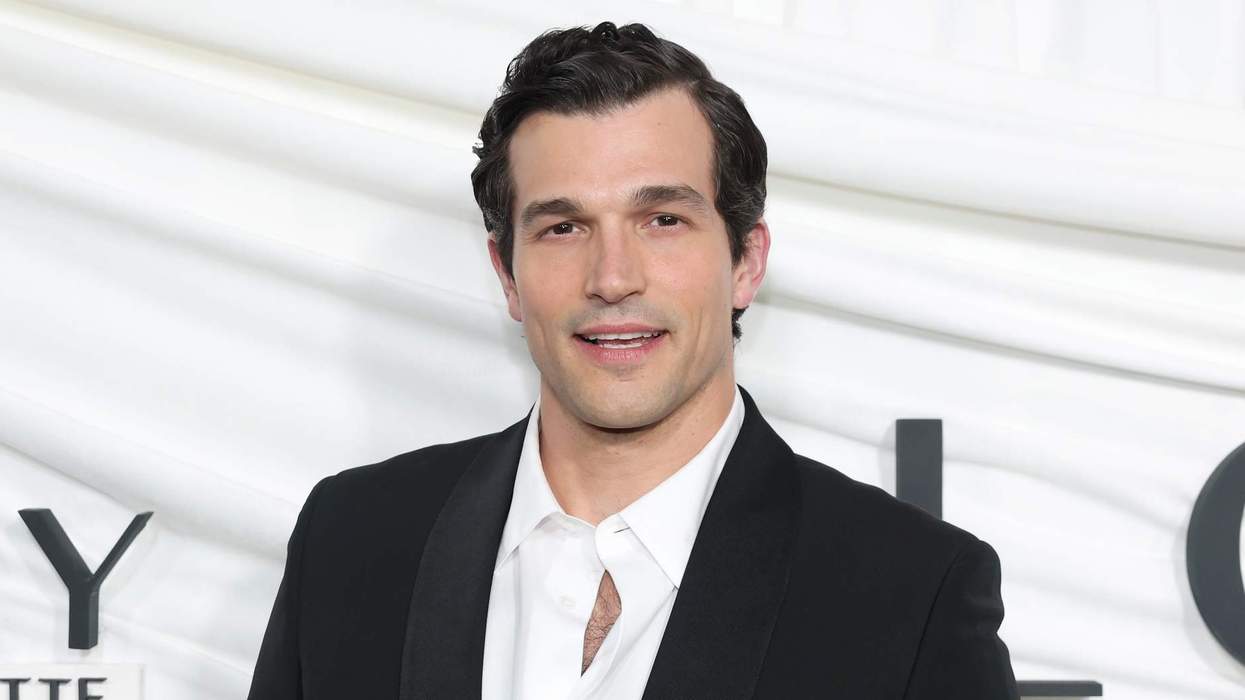

Collaborating with Celine Sciamma, who made last year's Girlhood (Bande de Filles) about a group of black French girls' adolescent adventures, Techine achieves the airiest-yet presentation of his weightiest themes, here subtly embodied by Thomas, an Algerian adopted by French mountain farmers and Damien, the son of a middle-class doctor, Marianne (Sandrine Kiberlain) and military officer (Alexis Loret). The film vibrates with personal and social tensions--submerged class resentments plus enlightened yet fragile civility. Thomas and Damien's open faces show it all and react to it as pressure on their innocence.

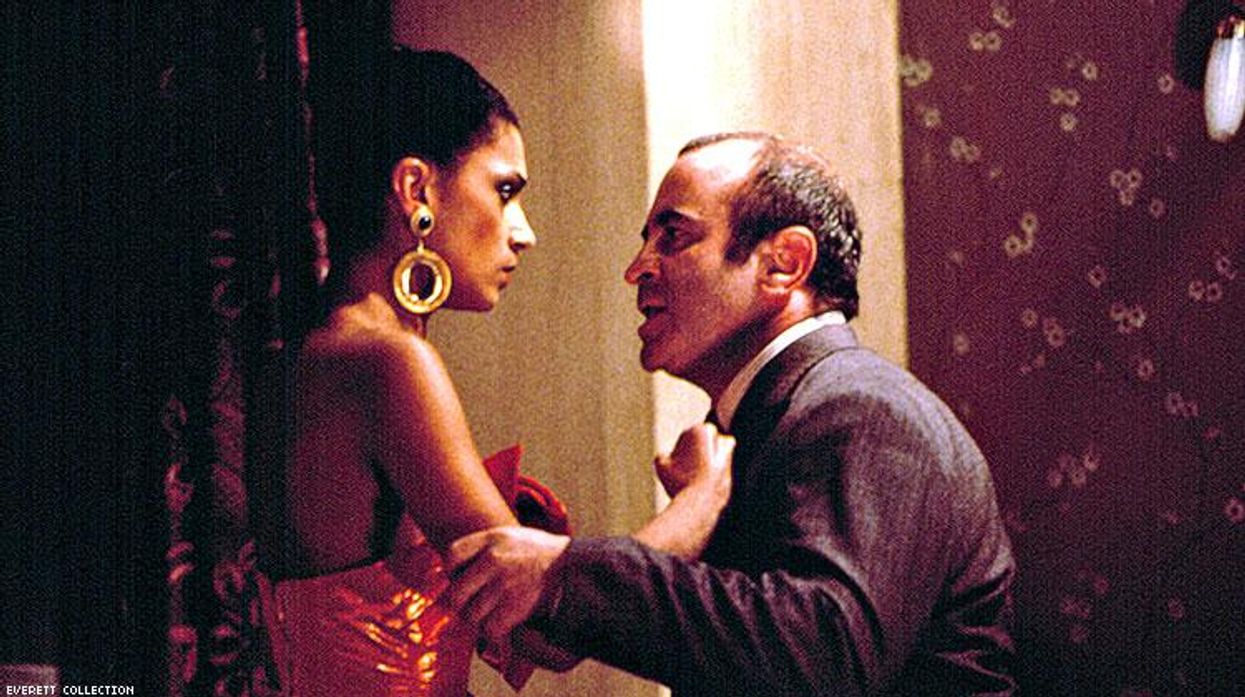

In Techine's 1987 film Les Innocents, two young men, Algerian (Abdel Kechiche) and French (Simon de la Brosse), were bisexual rivals for a woman (Sandrine Bonnaire) who felt ambivalent allegiance to them both. The story addressed post-colonial France's racial and political anxieties and morality represented by attractive, romantic figures and it ended--unforgettably--like Greek tragedy: Kechiche and De La Brosse, side-by-side, staring wide-eyed into the hereafter.

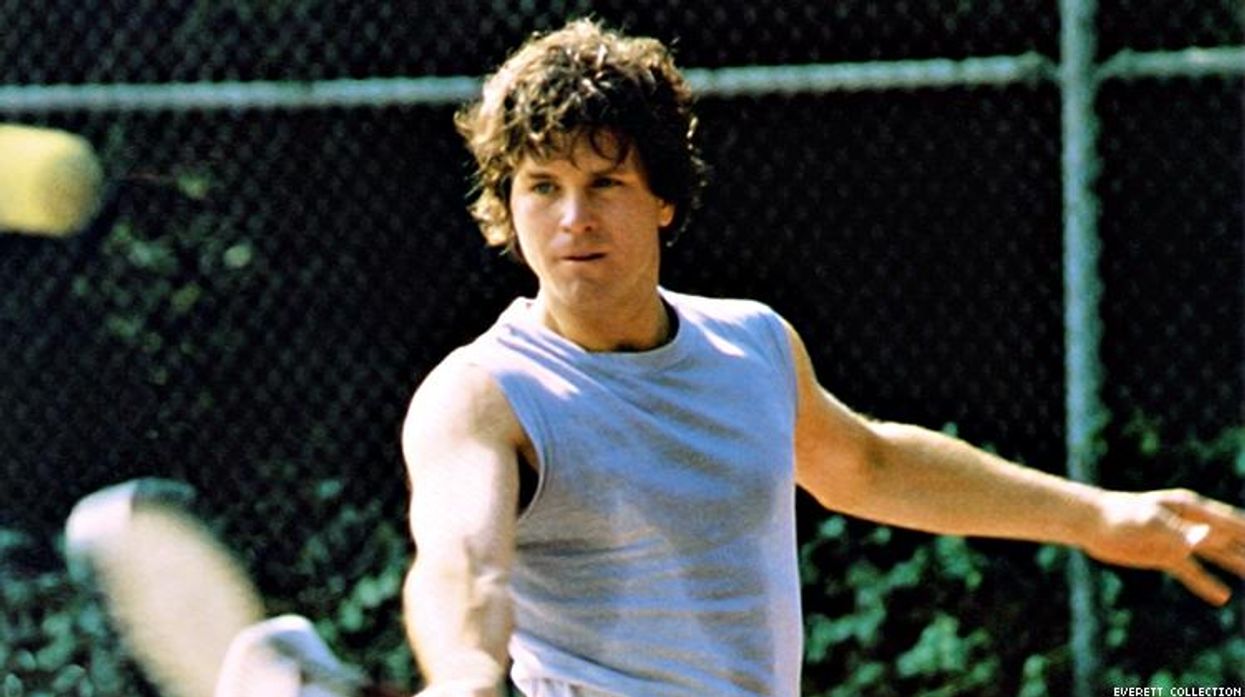

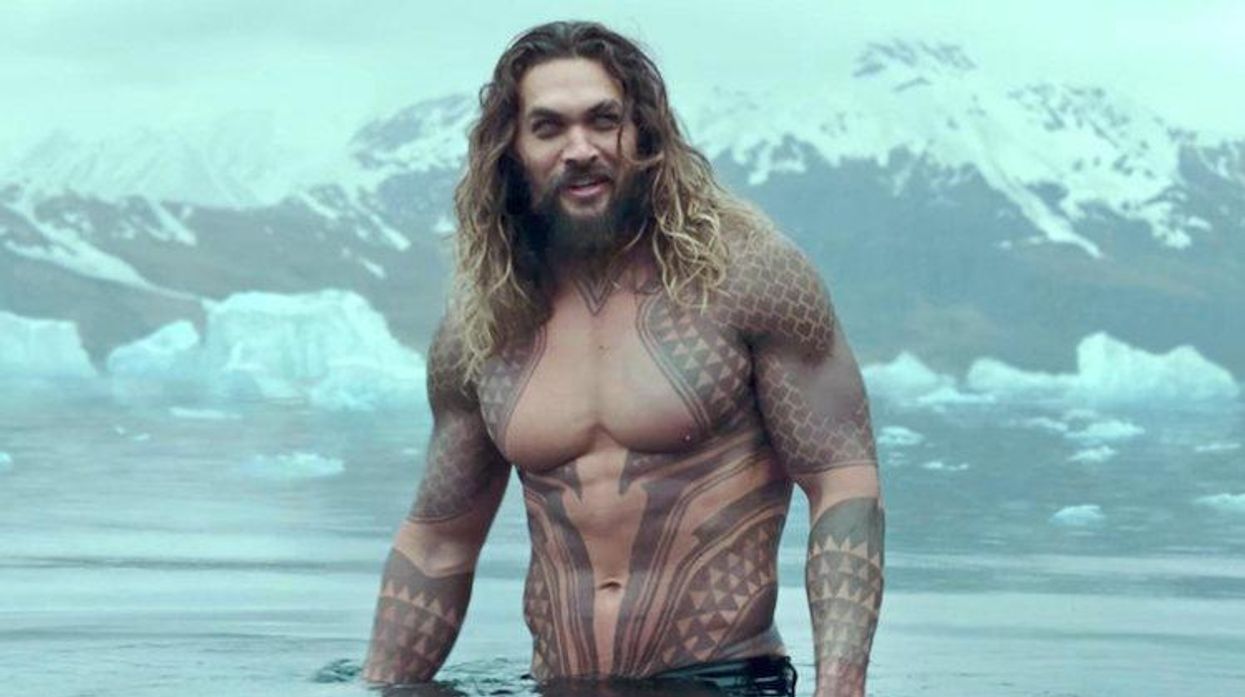

Thomas and Damien resemble that great image as they circle each other: Similar types with slim bodies and short, scruffy haircuts, their millennial twinship defines the homosocial and the homoerotic. They experience the age's sexual confusion on top of their stress at home. Thomas is physically outgoing but strains to study hard, pushing himself past an adopted child's insecurity. He develops self-sufficiency on the farm and in nature, exercising his solitude by swimming nude in an icy lake. (He's teased by his father about seeing a live bear in his dreams.) Damien is brainy and aesthetic: He recites poetry, wears a blue stud in his left ear, likes to cook and takes self-defense lessons. ("Physically you're progressing, now work on your attitude. You sound all girly" says his trainer.)

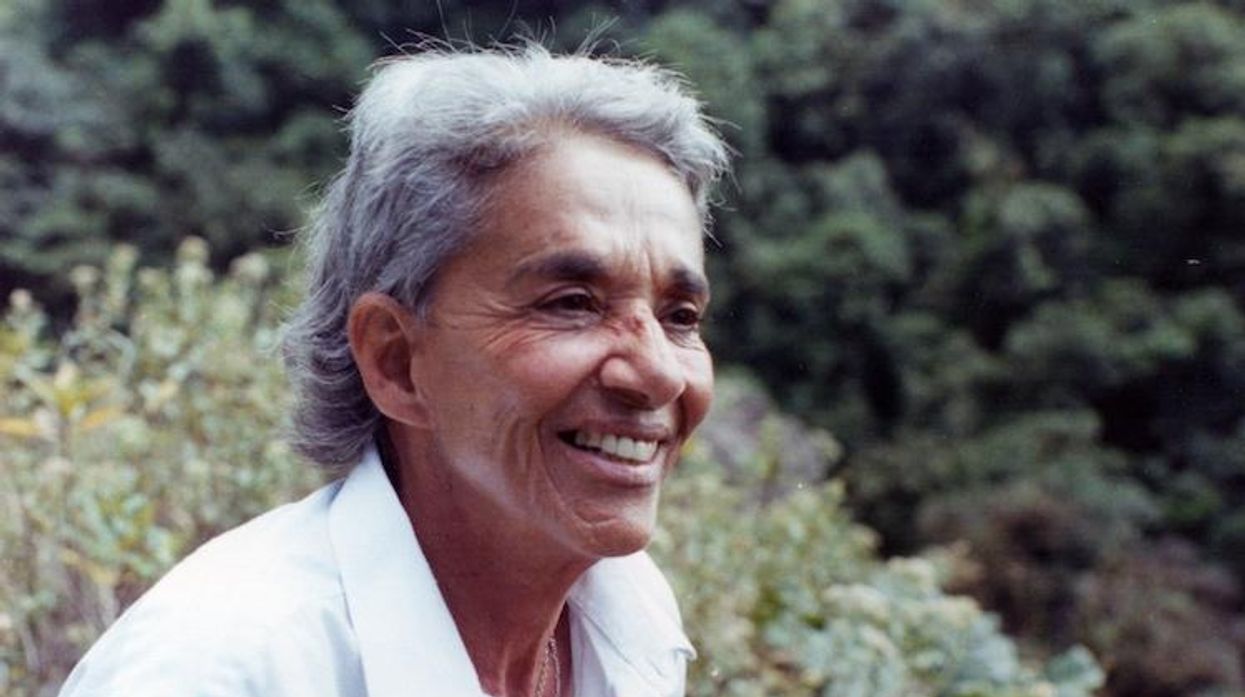

Neither boy fits the macho/femme stereotype but their sensitivities overlap. Thomas' fear of abandonment equates to a need for love while Damien, lonely even in his comfortable family life, is ready to fulfill his need for intimacy. I can't think of any other movie that made verging on adulthood so clear and moving. Techine and Sciamma deepen it with the adult parents' difficulties, particularly Damien's mother goofy but grounded Marianne; they all struggle to achieve and teach civility. Despite social differences, they understand their particular privilege--its risks and its obligations. Thomas and Damien come to realize it, too, as in the scene of a potential Internet hook-up that ensnares them both.

Thomas and Damian's relationship grows awkwardly yet Techine's view stays graceful Techine shares Jean Renoir's extraordinary compassionate view--"Everyone has his reasons"--to include close-at-hand gay observation that is rare in movies. Seeing past villainy brings out better understanding of human nature and unpredictable life. When contentment between Thomas and Damien is suddenly broken, Techine avoids familiar dramatic emphasis, but grasps the emotional texture and existential sensation of being alive--his characters' love and fear takes the narrative by shock. Perfect for seeing life as a process of finding confidence.

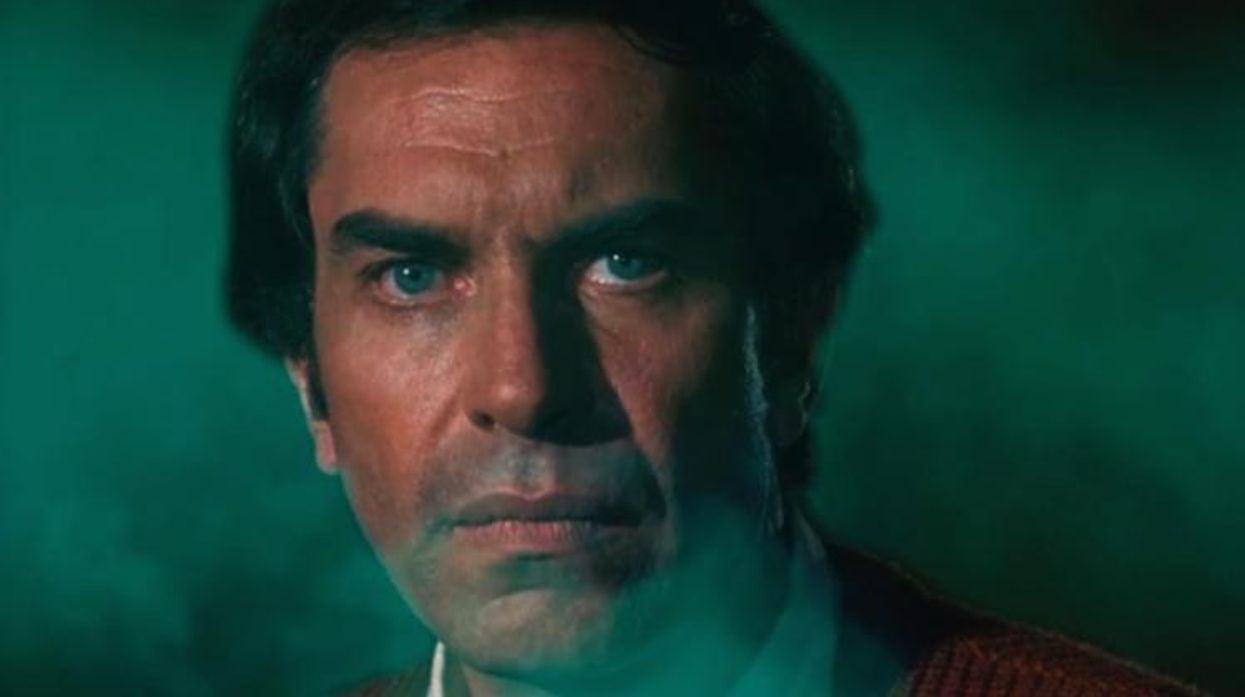

Julien Hirsch photographs resplendent vistas of mountainous suburban France (Thomas likes to hike and introduces Damien to countryside hideaways and promises to guide Marianne at her neediest moment). But Hirsch's lithe camerawork is especially good at catching fleeting emotions: Alexis Loret's endearing Skype conversations and especially the boys' fast glimpses of ardor and hesitance. Their complex first love is apparent even beneath their angry surface--the most natural-seeming acting in any movie this year.

Related | Who is the Greatest Gay Filmmaker Alive?

No other intellectual filmmaker tells stories as nimbly as Techine. When I suggested he was the greatest living gay filmmaker, the jest was to simply rank him among cinema's best. Being 17 isn't simply a teenage escapade; even though Techine's style has morning-wood thrust, it's really about multi-level, big-L, love. When Thomas and Damien's homework session researches philosophical statements on desire (from Plato to Leibniz) the highbrow flirtation is more than heady and profound. It's romantic, too. Ever felt like you could watch a single movie all day long?

Being 17 is now playing in select theaters.