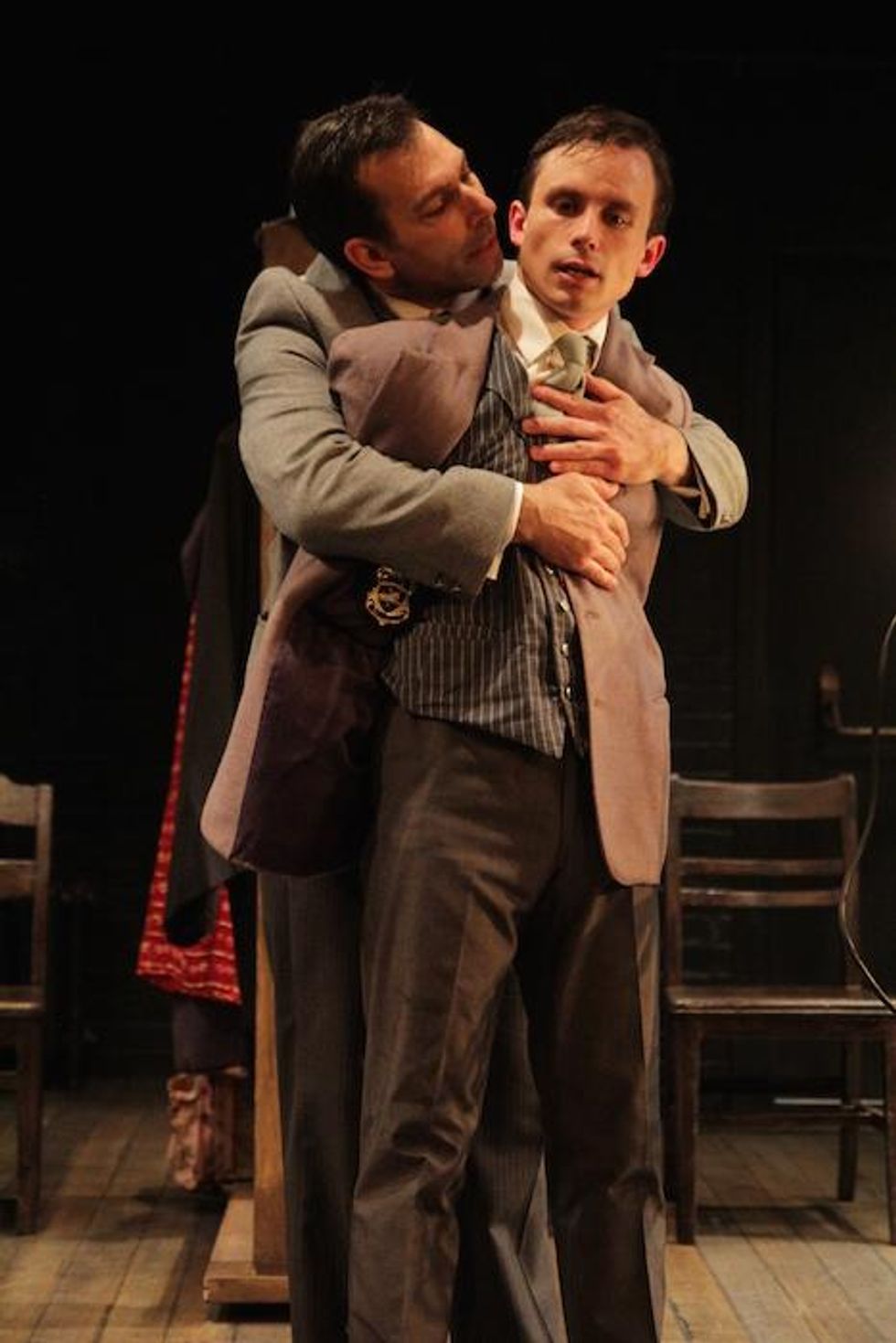

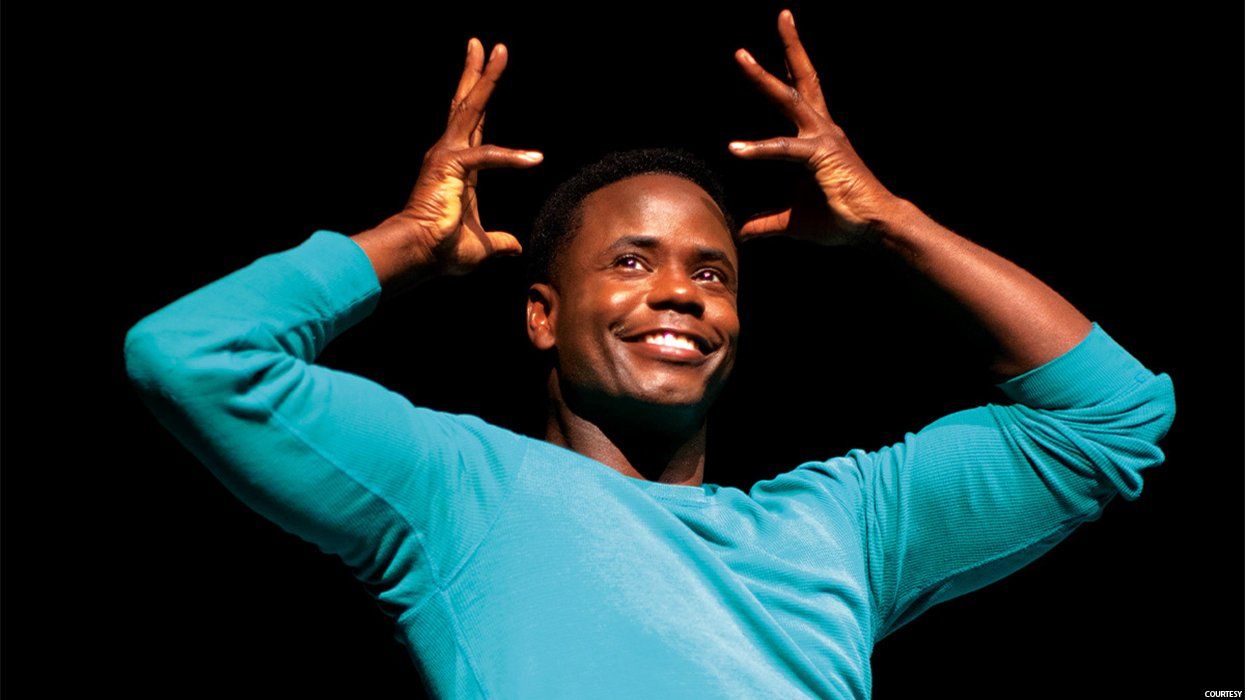

Robert Mammana and Will Bradley in 'Twentieth Century Way' | Photo by Brittanie Bond

Every so often a brilliant theatrical production just doesn't affect me emotionally, but leaves me spellbound in contemplative thought. This is not to say that the play is not emotionally effective. It's simply that my logos is kicked into overdrive, and my pathos takes a time out on the bench. Until recently, the last time I personally felt this way was when I saw David Ives' Venus in Fur at The Alley Theatre in Houston, and now Tom Jacobson's The Twentieth-Century Way at New York City's Rattlestick Playwrights Theater holds that distinction as well.

Initially, the audience is led to believe that this play is set in a theater toward the end of the first quarter of the 20th Century. Yet, through some brilliantly constructed machinations of theatrical revelation, the audience comes to see the actors in their most vulnerable states. Starkly naked and stripped of all pretenses, the final moments seem to be occurring simultaneously in the past and present. For the previous 80 or so minutes, the audience witnesses actor Will Bradley as B. C. Brown, a handsomely delicate young man, and Robert Mammana as W. H. Warren, a more rugged and mature man. At the end, the lines that separate us from the actors are blurred, and we are invited to see them as Bradley and Mammana. Much like the characters in Venus in Fur, the two actors engage in an engrossing battle of the wits via a complicated improvisation exercise. The men use their accumulated skills in drama to pervasively one-up the other, with the game set to end once one shows signs of flagging exhaustion.

But, the conflict in The Twentieth-Century Way isn't a fun exercise. It begins as a game to determine who gets to audition for a film role that both actors are chasing, and that barely scratches the surface of the work's true drive and purpose. Historically, Brown and Warren were actors hired as "vice specialists" by the Long Beach Police Department during the summer of 1914 to entrap and arrest gay men in private clubs and changing rooms. Through Tom Jacobson's words, Michael Michetti's unflinching direction, and Bradley and Mammana's bewitching performances, we come to know Brown and Warren as one layer of persona that the actors must wear in the show. In addition to these two men, they morph -- sometimes at dizzying speeds -- through a whole slew of characters. Often these changes are signified with a flower put into a pinhole on a lapel or by a new hat, but in some occasions the jumps occur so quickly that Bradley and Mammana must solely rely on mannerisms and vocal tones to convey the shifts, which they do with laudable aplomb.

Yet, it is through adding these multifaceted layers and differing personas to each actor that Jacobson's play finds its merit and purpose. Not so much a history lesson on the heinous laws working against homosexual men in the early 1900s, The Twentieth-Century Way is an examination of the roles we play. Are we ever our true selves? Are we ever free from pretense and the walls we construct to protect our hearts and souls? Bradley and Mammana wear many different skins in the show, but by the end the pair of actors are laid completely bare before us. Refering to each other by their real names, they acknowledge that they are being watched by an audience. The audition they are competing for becomes a metaphor for how every action is, in a way, an audition. We audition for jobs, dates, friends, and more. We look at the exteriors and determine worth without knowing if the outsides match what's inside. We withhold. We hide. We come out. But are we ever comfortable enough or passionate enough to lay everything bare? And if we are, what does it take to get there?

Don't expect the cast and crew of The Twentieth-Century Way to answer these questions, but they'll give you plenty of nuggets to chew on as you digest the work and think about these and the others questions it posits. Audiences are treated to one of the most intense tennis matches of dramatic wit written for the stage, and unlike Venus in Fur, I'm not sure this one doesn't end in a draw.

The Twentieth-Century Way continues through July 19 at Rattlestick Playwrights Theater, 224 Waverly Place, New York City. For tickets and more information, visit Rattlestick.org.