Growing up in Galesburg, Illinois, a small town in the Midwest, I rarely (knowingly) ever met queer people.

There was the couple that owned the best café in town, the voice professor at the community college, and that was about it. And then, of course, me. There weren’t social media influencers to follow or forums to find solace in; the internet loaded one horizontal bar at a time back then, and the isolation was often tough.

Because of that, going to college in a bigger city was imperative, no matter the cost. I stayed in the closet until I got to my university campus, came out from day one, and tied up loose ends later. Kissing boys, going to gay bars, and making queer friends affirmed that cities were my thing and that the pros outweighed the cons.

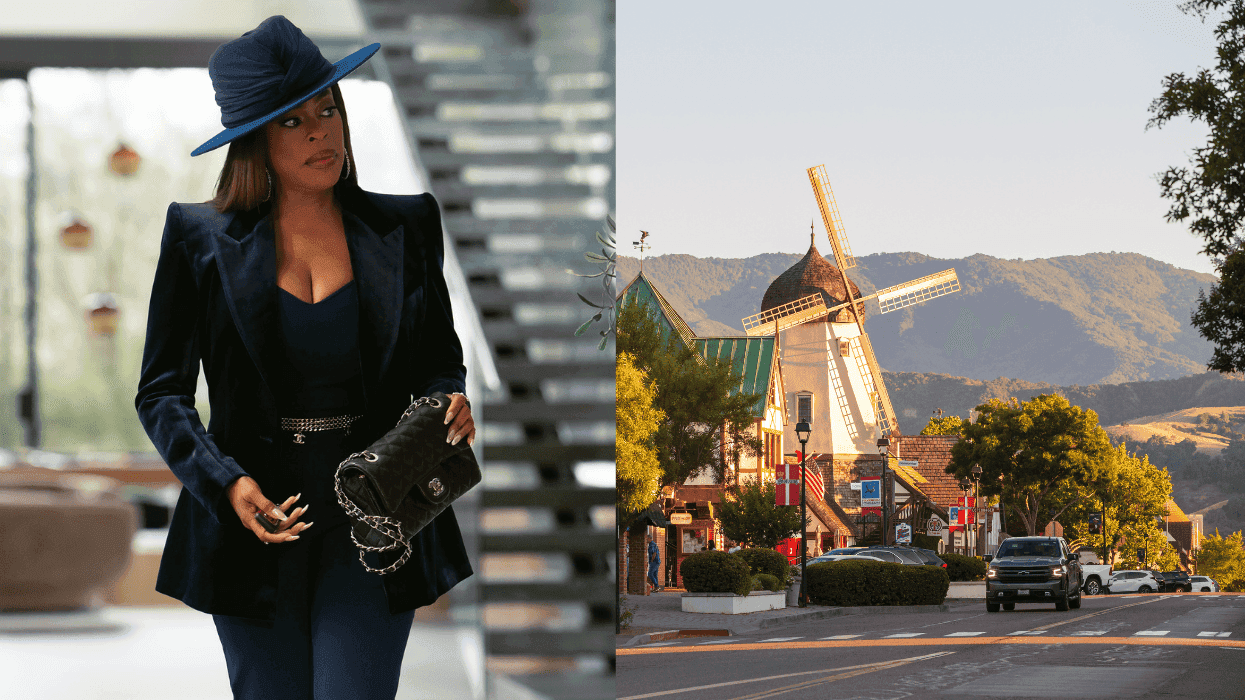

Cities have long been magnets for queer community and belonging. “If you need to interview someone who’ll never leave the city, no matter what, that’s me!” said a dozen friends of mine here in Los Angeles when I told them I was writing this article. For some, city life is a nonnegotiable, despite the sometimes eye-watering price tag.

But for others, both queer and otherwise, the cash crunch has magnified, with factors like gentrification, inflation, and housing shortages continuing to ratchet up prices. You’re not imagining it: From 2020 to 2022, nearly everything became more expensive, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting an average increase of 12.45 percent across all categories of goods in that period.

Add to the mix the rise of the hybrid workplace—and the ability to further your career without a brutal commute to the office —and cities start to lose their luster. As remote work becomes increasingly mainstream, many people have wondered, “Should I stay, or should I go?”

Queer People Statistically Earn Less

The skyrocketing cost of living exacerbates queer people’s incomes, which are already stunted. LGBTQ+ workers earn 10 percent less than their nonqueer counterparts, according to an analysis of 6,816 LGBTQ+ workers by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Additionally, LGBTQ+ women earn 13 percent less, trans men 30 percent less, and trans women 40 percent less than the average American, as reported by the BLS.

For DeVante Love, a spiritual therapist and past Gay Games martial artist, metropolitan life was taking more than it was giving.

“I just realized that New York was literally sucking me dry and wasn’t providing enough resources to make up for what it’s taken away financially,” says Love, who now resides in College Station, Texas, home of Texas A&M University. “My rent went from about $2,000 a month to $700 a month, including utilities. I saved a tremendous amount on rent. I wasn’t going out as much.” Moving to College Station helped Love pay down his $65,000 in student loans in two and a half years.

“The daily living expenses of entertainment and Broadway shows and going out to fancy dinners and parties, I wasn’t doing all of that stuff anymore,” Love says. “So I saved, honestly, about $1,000 a month on that, given the different things I was doing at that time.”

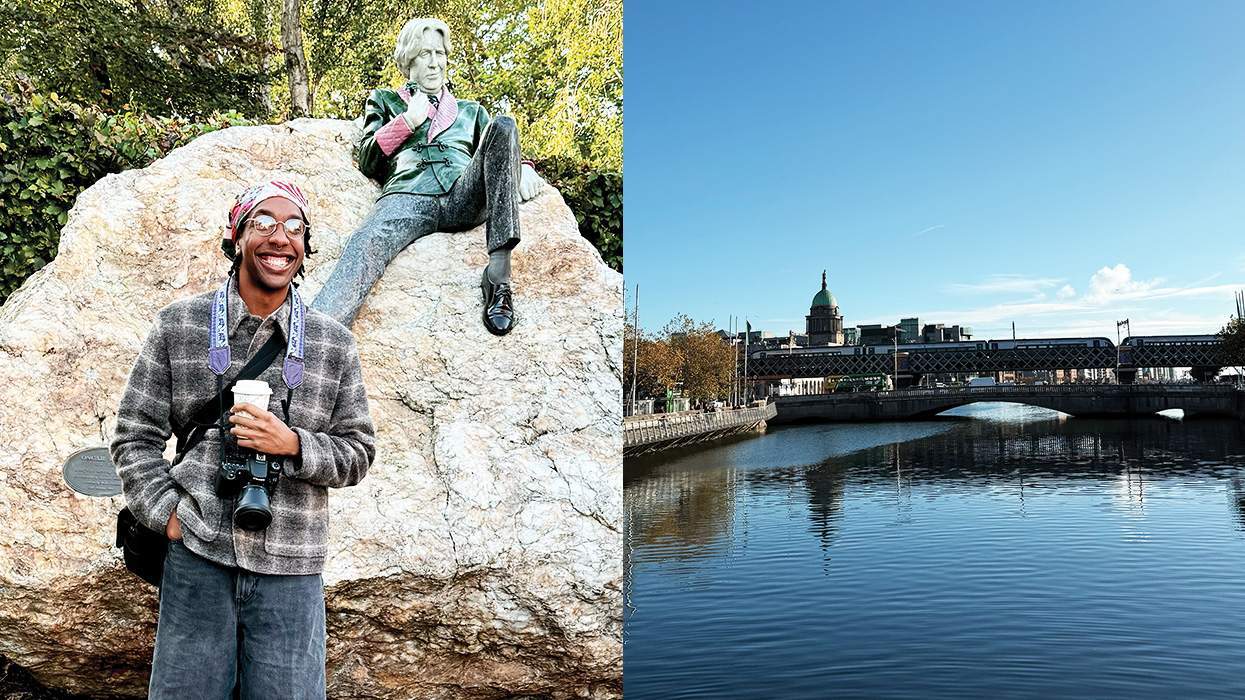

Nevertheless, an initial move to a metropolis can be an opportunity to discover your queer independence and identity, says Ashley Couto, a writer now based in Montreal.

“I was a suburb girl. I grew up in a very white, Christian, conservative suburb,” she says. “So I moved to the city for college.” After graduation, and upon accepting a job that allowed for remote work, Couto then moved back to the burbs to save money. “I needed a break from the noise and paying an astronomical amount of money for like no space in the city,” she adds.

After taking time to pad her savings account, Couto moved to Toronto to have more in-person opportunities at work. But when her boss relocated, the numbers again became difficult to justify. “I knew I could get more space in Montreal for less money than what I was paying in Toronto,” she says. “I was paying $2,600 a month for under 500 square feet, versus now, where I pay $1,650 and have 1,500 square feet.”

Money and Community: Both Important Resources

Chronic stressors like not having enough money wear us down. But so can a lack of community. Societal stigma impacts mental health and can make queer people more susceptible to increased anxiety and depression, says Jack Turban, MD, assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

“There are things that can buffer against the negative impacts of societal stigma on queer mental health,” Turban states in an email. “Prime among these are community connectedness — having other queer people in your life to remind you that you’re not alone — and pride in the queer community, remembering that queer people are bright, vibrant, and successful members of society.”

Turban adds that moving to a more rural community “can sometimes coincide with a loss of these protective factors” and that these supports should be taken into consideration when weighing your options.

“Ask yourself some important questions,” Turban says. “Do you need other queer people around to be happy? Is this new environment going to accept you for who you are? Will you feel pressure to go back in the closet? If you move away from your support system, will you still be able to connect with them enough virtually or through trips? I find that people often underestimate how important it is to be close to their social supports, especially when those social supports are chosen families.”

Rural communities may inherently have fewer resources, but the pandemic-fueled innovations in telemedicine help offset some of these concerns, said Randolph Hubach, associate professor of public health and director of the Sexual Health Research Lab at Purdue University.

“We know that rural LGBT people are less likely to have explicit nondiscrimination protections and are more likely to live in areas with religious exemptions that allow service providers to discriminate or not serve them,” Hubach says. “But we do know that rural communities include tight-knit social networks, which some LGBT individuals have found welcoming and also comforting. You can find LGBT-affirming medical practices that offer telemedicine options, and with the advent of self-testing, where you’re able to collect samples at home, that’s more of a reality within rural spaces.”

In response to Love’s relocation from Manhattan to College Station, Hubach also notes that college towns can provide a “semi-rural” environment that provides the best of both worlds.

“These college towns have a very different flavor compared to other areas of rural America,” Hubach says. “College towns bring in a larger number of students who come from different generations and also have a tendency to bring other LGBT individuals into those spaces. So the decision to move into a rural college town might look different than moving into a rural noncollege town.”

Temporary for Some, Permanent for Others

Some who’ve left the city say they’re itching to return. “Finance-wise, I’ve been in such a weird place in my life, because I ideally want to be back in the Bay [Area],” says Chris Cobarruvias, who finished graduate school in the spring of 2020, then opted to move back home to Oakdale in light of the pandemic.

“As far as my community, it’s been really tough and tricky,” they say. “There really isn’t an LGBTQ+ community in this little town that I went to high school in, that I grew up in but then very much grew out of. I found myself more in the Bay Area.”

Cobarruvias’s relocation has created momentum around saving money to one day buy a home. “I’m literally saving $4,000 a month,” they say. “But it does feel lonely. I find myself going to the Bay often.”

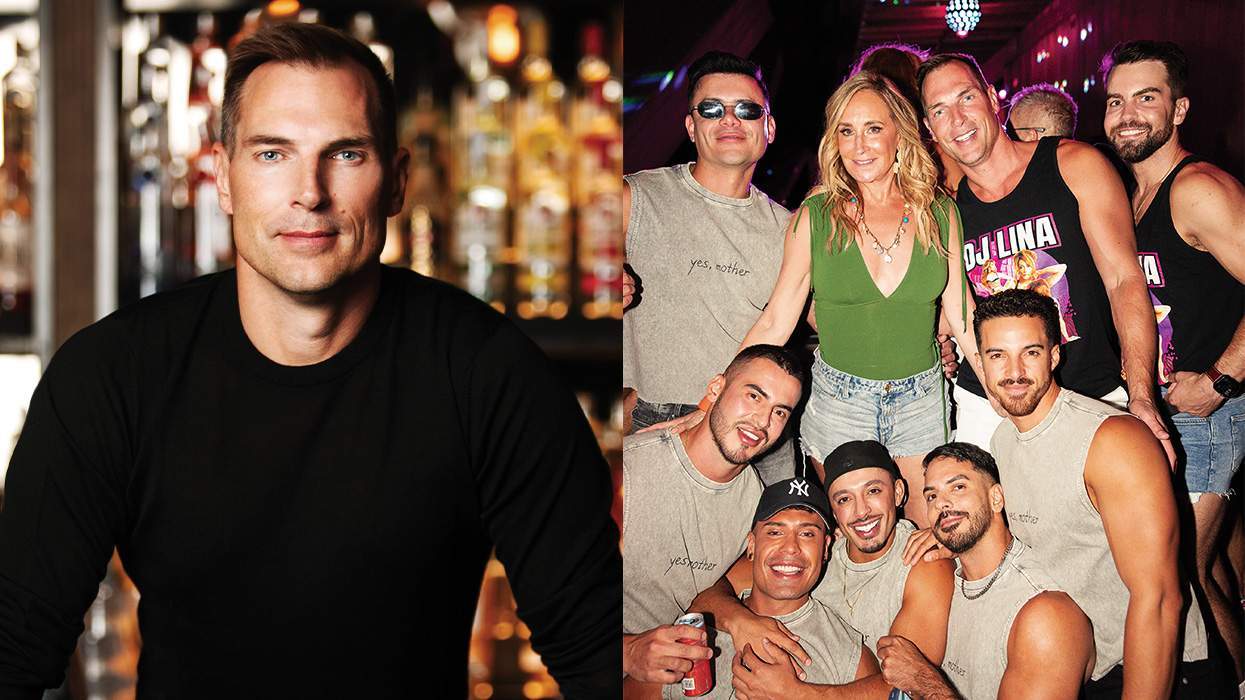

Others were ready for a more permanent change. For Andrew Velázquez, a makeup artist of 23 years, a cross-country relocation enabled the financial cushion needed to bring ambitious projects to life.

“I love Los Angeles, am an Eastsider at heart, and never thought I would live anywhere else,” he says. A lifelong Angeleno, Velázquez and his husband relocated from Echo Park to Florida last year partially to leave behind the exorbitant cost of living, a change he said slashed their monthly expenses by 70 percent. “I finished writing a book, and I finished creating my makeup palette,” he adds. “Long story short, I was able to launch my brand.”

Velázquez says the current political climate made him hesitant at first. “Do we like the politics? No. Do we like our governor? No,” he says. “As POC queer individuals, I had a lot of reservations — I was really skeptical about it.” But the relocation gave him a new financial perspective.

“You don’t realize how much goes into living in California because it’s just kind of your culture,” he adds. “You don’t question the $6 gas, the $20 sandwich, or the $10 coffee at Whole Foods — you know what I mean?”

Find What Works for You

Love sees small-town living as a forcing mechanism for deeper relationships, and a way to sidestep the sometimes transient friendships that inevitably come with metropolitan living.

“When I was in New York City, I wasn’t able to build really strong bonds with people,” they say. “So I knew that coming here, I would have a smaller, tighter group, which was helpful for me. I did a lot of volunteer work with different LGBTQ+ groups, and that got me exposed to the younger queer population, [who are] very well connected online through different social media spaces.”

Online communities can fulfill a need for belonging that may not always be available in person. But not all online queer spaces are supportive, notes Turban. “For example, geosocial networking applications — i.e., dating or hookup apps — can often contribute negatively to mental health, whereas moderated online safe spaces like TrevorSpace can be protective for mental health,” he says.

Queer creatives often thrive online, but after brutal COVID-19 quarantine restrictions, many are craving more in-person interaction. “Montreal is full of queer activities,” Couto says. “As a queer person, it is a place that has the kinds of activities I want. Queer trivia, gay bars, and other queer people, which is great for dating. It has the amenities I wanted.”

It’s important to spend time researching what next steps are right for you. Hubach suggests trying before you buy. “It might be worthwhile to just go get an Airbnb and stay for a week or so,” he says. “Give rural communities a try — you might actually like what you see.”

As you ponder your decision, be sure to set fear aside along the way.

“You have to take risks, you have to step out of the box, and do things that are out of the norm,” Velazquez says. “Especially for us as queer people. We’re the most creative, we’re the ones that make shit happen — we make the world go round.”

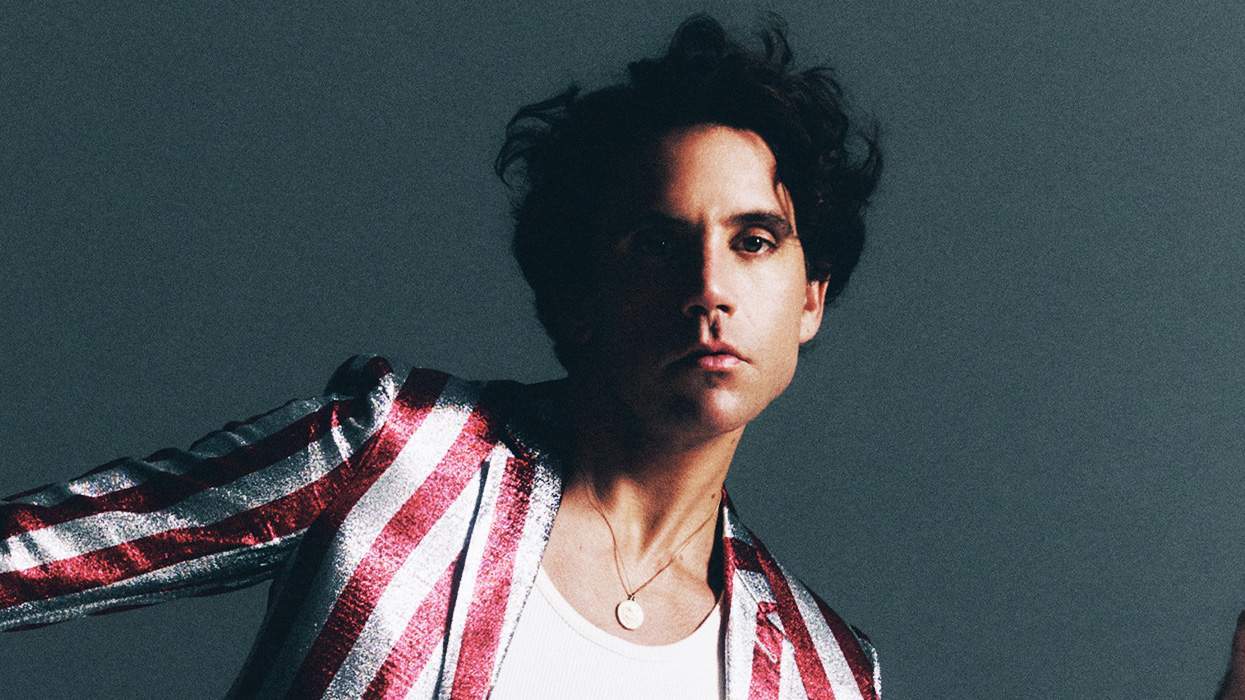

A self-described “editorial mutt,” Nick Wolny is a journalist and consultant. He writes about money, business, LGBTQ+ life, and how they intertwine, and has previously contributed to Fast Company, Business Insider, and Entrepreneur magazine. Join his newsletter at nickwolny.com.

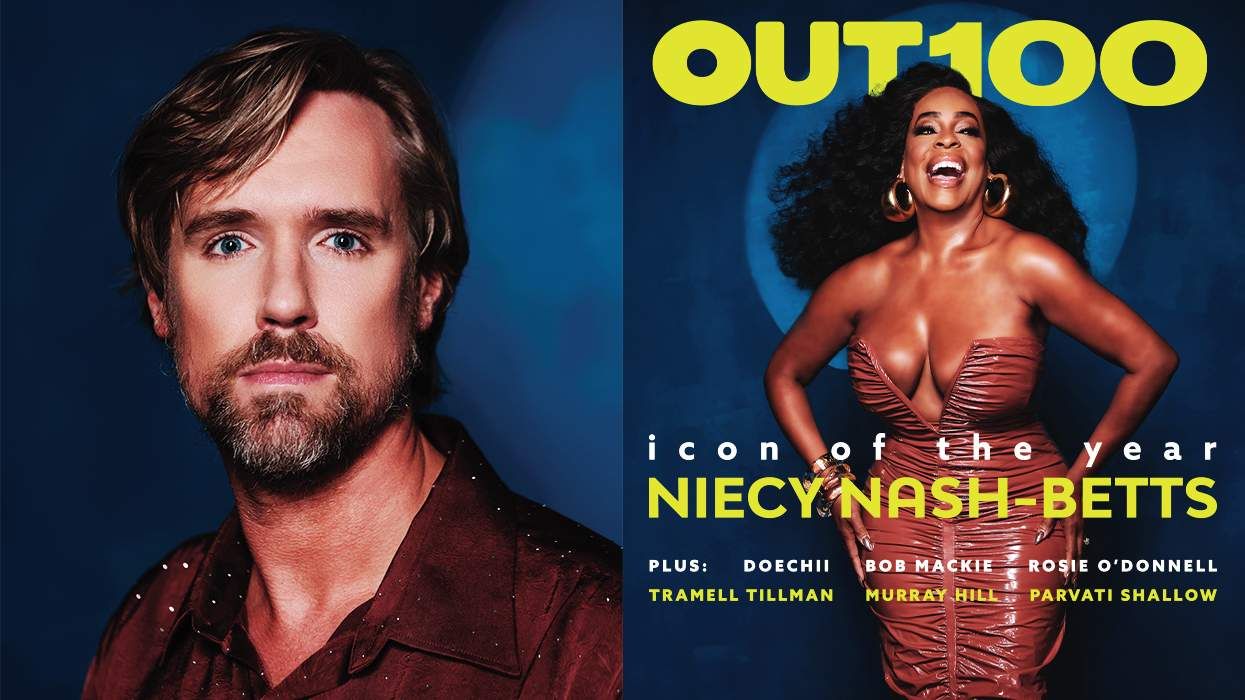

This article is part of the Out July/August issue, out on newsstands July 4. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.