Lenny Zenith's rock legacy is as legendary as it is quiet. For over three decades, the New Orleans musician has released music with bands that include Jenifer Convertible and Tenderhooks and opened for everyone from U2 to Iggy Pop. But, long before he hit the stage and recording studios, his legacy began in the registrar's office of a Glendale, California junior high school.

It was in the parking lot outside of Toll Junior High that Lenny's Methodist father sent him in alone to register for eighth grade after moving to the town following a divorce and it was here that Lenny forged a new identity. Leaving the male and female checkboxes blank, Lenny began to pass as a boy. "I assume some teachers were confused but, to my surprise, I was never challenged," he explained to OUT. "There were no GSAs, reality TV shows, or advocacy groups then, so I just navigated the unfamiliar landscape as well as I could -- often fearful, but always hoping for the best."

Related | Breakout Pop Star Kim Petras on Her Debut Single & Transgender Visibility

It was an auspicious and casual beginning for Lenny as he lived as he was meant to live. Now, over 30 years after his quiet transition, he has crafted a legacy in rock and roll as one of the genre's first true transgender rock stars. On tracks like "Suddenly Someone" and "Still I Rise," he sang about his trans identity -- amassing a loyal fanbase along the way.

We caught up with quiet rock legend as he prepares to release What if the Sun, his first album under his own name, and a book called Before I Was Me. Listen to the exclusive premiere of his new track "Sunday Dress" below and see what the musician had to say about transgender bathroom laws, the danger of being out, and being visible for a new generation of trans kids.

OUT: You transitioned as [a junior] high school student in the 1970s. Tell me about that experience. Did you tell anyone?

Lenny Zenith: It was very lonely. I couldn't tell anyone the truth. My dad was a Methodist minister and didn't know what was going on -- he never asked. My dad and I moved to Glendale, CA from Louisiana when I was fourteen. He dropped me off at Toll Jr. High and told me to "go in and register for eighth grade." There were no parental signatures required back then and he believed I should be quite independent.

When it came time to check the Male/Female checkboxes on the application, I left them both blank. Since I had been called Lenny since early childhood and was already very androgynous, it was relatively easy to pass as a boy. I assume some teachers were confused but, to my surprise, I was never challenged. There were no GSAs, reality TV shows, or advocacy groups then, so I just navigated the unfamiliar landscape as well as I could -- often fearful, but always hoping for the best.

I made several friends that year, and they all accepted me as just Lenny. Not one person ever questioned me. I felt truly accepted. That year was the first time I lived as a boy and actually played rock music in front of an audience at the school talent show. We played "China Grove" by the Doobie Brothers. When I left Toll to go back to New Orleans, my classmates made me a big card with lots of farewell wishes. It was decorated with a black construction paper star that said "Lenny" in gold glitter. "We love you!" was on the inside. I still have it somewhere. When I returned to New Orleans, I completed high school as a boy attending the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts and Spectrum High. I didn't ever dare tell anyone I was trans until I was a senior.

The friend I told, told their dad, who called the school, who then called my dad. He was surprised and asked, 'Lenny, what have you been up to?' I answered that I'd been 'going to school as a boy since eighth grade.' He really had no idea. After the disclosure, the school asked me not to graduate or go to prom with the class, and issued a 'graduation certificate' a few months before graduation. I'm not sure they had a protocol for handling that situation at the time. I was disappointed and felt isolated, but was grateful that I hadn't been beaten up or gotten myself or anyone else in trouble.

There's been a lot of discussion about transgender bathroom laws, especially in schools. How did you navigate this when you transitioned? How does it feel to see it now as a national issue?

It's utterly ridiculous, discriminatory, and based on fear and lies. We have all been using the bathroom with trans folk for years (I've been going to the bathroom my entire life, often public ones). Most people use stalls with the doors closed, do their business and leave. All through Jr. High and High School I tried to used isolated bathrooms, went during class, or just held it. I learned how to pee really fast and standing up. Today, I'm fairly certain that, with my facial hair and appearance, people wouldn't want me using the women's bathroom.

When did you publicly come out?

That's a complicated question since I transitioned relatively early. Even after performing publicly as a guy in New Orleans for many years, there was never an official 'coming out' event. The first time it was ever written about was in a review of my 90s band Jenifer Convertible, when the 'zine Jersey Beat, declared I was transgender.

The press in New Orleans was very delicate about the issue in the 80s. In the 90s, it was actually still somewhat dangerous to be openly transgender. There was Jayne County and Chloe Dzubilo among other trans performers, but I heard that a booking agent at an East Village club in NYC wouldn't book my band, saying, 'We don't want that freak playing here.'

As one of the first trans musicians, how does it feel now to see mainstream transgender talent in music and other industries like film and TV?

To be perfectly honest, it's a little bittersweet after devoting so many years to my music. I'm so glad other artists are being acknowledged, honored and getting recognition. I'm very grateful to have this opportunity now! I wish I would have had the courage and presence of mind to be more out and not as 'stealth' years ago, but it was challenging. I always wanted any acclaim or notoriety to be more about the music than about my persona.

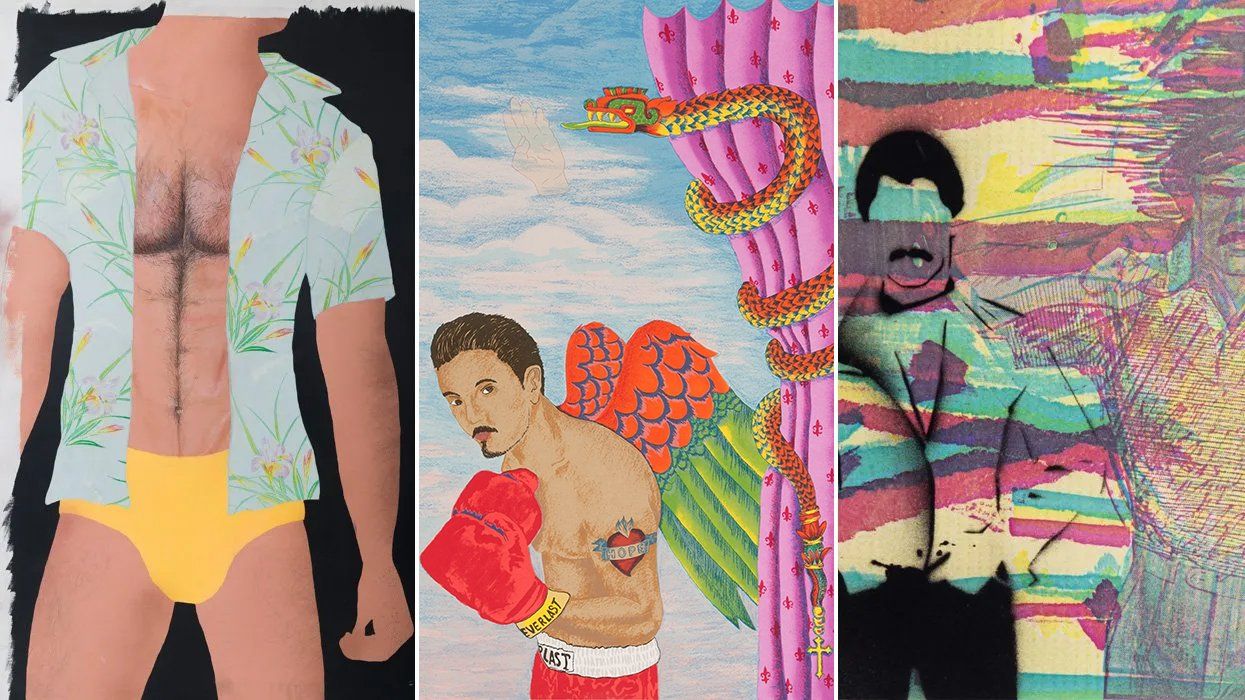

It was difficult navigating the cis male-dominated music industry, as I never met the narrow standards of the 'male rock icon.' Although cis men could play with gender (Bowie, David Jo, Iggy, Boy George), there were no trans male figures at all. Jenifer Convertible had several songs about the trans experience (including "The Car Song" and "My Boy Bill"), and our album was called Wanna Drag?.

All my friends, my bandmates, and many fans knew. They were very supportive. There was just not much in the way of public forums for being out and visible then, and when there was, I demurred. I was just becoming more comfortable with being more out, but I had a job at a major music publishing company and was worried about losing my health benefits that I needed for hormones and therapy. In retrospect, I wish I would've been -- or could've been -- more fearlessly out twenty plus years ago.

Tell me about "Sunday Dress." What does the song represent for you at this point in your career?

While living in Ann Arbor, I visited and played in Detroit frequently. I became more acutely aware of income inequality, racism, the weakening of unions, the impact of automation and the rippling economic and emotional effects those things had on communities. People were struggling to find work and make ends meet. Neighborhoods were abandoned, and the once vibrant and bustling city struggled. It was palpable. The longing for basic things, like a pretty Sunday dress, is an expression of the frustration of not having quite enough. Thankfully, Detroit is experiencing an artistic and economic renaissance, but it's a story reenacting itself all over the country.

You've got a new memoir coming out called Before I Was Me. What was life like before transitioning?

Again, it was very lonely. There was very little visibility for trans folk -- especially male-identified ones -- beyond New Orleans' French Quarter, which I gravitated to. There was no one to talk to about it, and it often felt like I was the only one traversing this terrain.

I'm forever grateful to the endocrinologist, and child psychiatrist at Tulane Medical Center for understanding what I was going through when my parents took me there at the age of twelve. There weren't a lot of clinical pathways written at the time, and they forged one for me. They saved my life. I experienced a tremendous amount of guilt -- feeling I was doing something terrible and disappointing my parents, but I didn't have a choice. I had to be true to myself and who I was. I was and am incredibly fortunate to have been surrounded by loving friends in New Orleans and later in NYC, and my family has come around. They've encouraged and supported me to be myself, no matter what.

How do you hope your career and music will help the younger generation of trans kids?

Now more than ever, I feel it's vitally important to be visible, out and proud. I want other trans people young and old to see someone, who despite many years of trying, continues to do something they are passionate about, and is finally fearless in being who they really are! This record is my love song to them and I hope to raise some awareness by talking to you and donating a portion of the sales to trans advocacy groups.