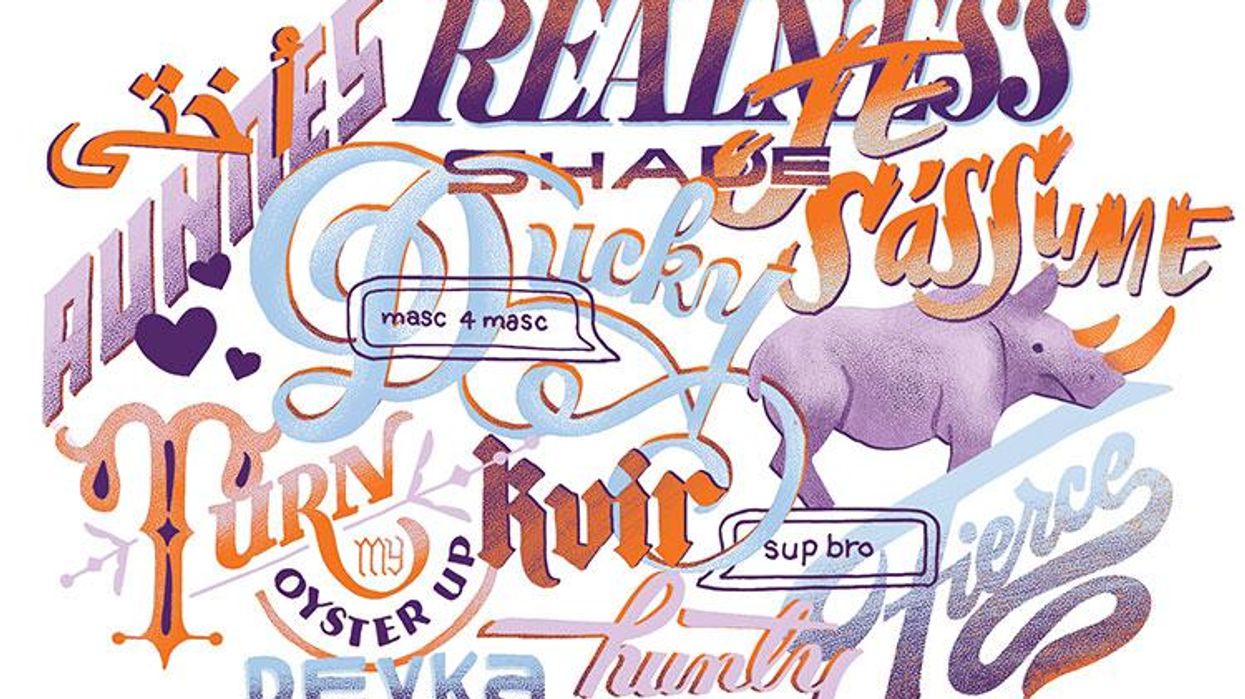

Illustration by Jill Dehaan

Bill Leap, perhaps the world's most respected scholar in the field known as lavender linguistics, talks in a Southern drawl and cusses like a trucker's wife.

"Let me tell you what it is, honey," he says on a Monday afternoon from his home in Tampa, Fla. "Miss Piggy's English is so queer."

Leap, an emeritus professor of anthropology at American University in Washington, D.C., is writing a book, Language Before Stonewall.

"Back in the '20s and '30s, there was this massive use in some social sets in gay America of French as the quintessential gay language, and that continues to the '70s," he says. "Honest to God, Miss Piggy spoke fluent gay English. The way she slips in these little French things, the use of 'moi' and the hand gesture to the bosom, this is so 1930s gay."

In 1993, Leap created the Lavender Languages and Linguistics Conference, now in its 24th season. The two-day event draws about 150 attendees from all over the world and is the longest-running LGBT-studies conference in the U.S., and the only one dedicated to language issues, according to Leap. In 1993, much like today, the community squabbled over language politics, starting with what to call the field of study -- queer language? Gay and lesbian language? Leap went with lavender.

"I thought, Let's use that ancient term 'lavender' and let's offend everybody," he says. Lavender, he points out, has been associated with the occult and mysticism, with women's power in Africa, and with forms of power in the West in the Roman Imperial Court and the Catholic Church.

"It surfaces in the 20th century with a lesbian women's movement in England, which was marked in public by women who wore lavender-colored rhinoceros pins on their lapel," he says.

In his current research, Leap is looking at Harlemese, the language of the Harlem Renaissance, where he cites a rich and dynamic queer presence and a manner of speaking that, while being not exclusively queer, has influenced both gay and mainstream language to this day.

"Harlem was the site for internal colonialism. Its sexual value was there for the convenience of white folks. But it had its own identity and formation in spite of the fact that white folks were intruding," he says.

Words like "hot" and "hunk," when describing an attractive person, came from the clubs and after-hours parties of Harlem, he says.

Around the same time, in Britain, Polari, what scholars call an anti-language, was at its peak among gay men, but the jargon would be completely unrecognizable to most English speakers today.

"Nada to vada in the larda, what a sharda," says Paul Baker, the world's pre-eminent Polari scholar, when asked about his favorite phrase.

Translation: What a shame, he's got a small penis.

"I like the rhyming," he says.

In the early 1990s, Baker stumbled upon Polari while looking for a thesis topic and soon found himself in a gay-run hotel in Brighton where the innkeepers recalled some phraseology. He talked to several old-timers in the area who helped him amass a small dictionary of words, numbering around 500 today and available on a new app called Polari, and wrote transcripts of dialogue from two popular British radio characters in the 1960s named Julian and Sandy, who spoke Polari. (Not coincidentally, the two actors playing the roles -- Kenneth Williams and Hugh Paddick -- were gay themselves.)

Polari has roots in 1600s England and is a mixture of Molly slang (Regency England men who dressed in drag and coined words like "bitch" and "trade"), thieves cant (the Elizabethan rigmarole of criminals, circus travelers, and other undesirables), East London cockney slang, and Italian brought home by sailors in the Mediterranean.

Other colorful Polari terms include: "pastry cutter" (a man's oral sex technique), "naff" (meaning either tasteless or heterosexual), "cleaning the cage out" (cunnilingus), "tipping the ivy" (tuchus lingus), "tipping the velvet" (oral sex), "he's got nanti pots in the cupboard" (he's got no teeth), your "mother's a stretcher case" (I'm exhausted), "vogue us up ducky" (light me a cigarette), and Hilda Handcuffs, Betsy Badge, and the orderly daughters (terms for the police).

"It doesn't always have to do with secrecy and protection," Baker says. "I think it also has to do with forming an identity as an affected group, as marking yourself as different, or maybe a bit superior in some way, a mind-set of evaluating mainstream society as somehow inferior to the Polari speaker's point of view."

Unsurprisingly, Morrissey was versed. The title of his album Bona Drag means "nice outfit." In his song "Piccadilly Palare," he sang, "So bona to vada, oh you, your lovely eek and your lovely riah." (So nice to see you, oh you, your lovely face and your lovely hair.) And in the song "Girl Loves Me," on his 2016 album Blackstar, David Bowie sang,

Cheena so sound, so titty up this Malchick, say

Party up moodge, nanti vellocet round on Tuesday

Real bad dizzy snatch making all the omies mad, Thursday

Popo blind to the polly in the hole by Friday

Translation:

Women, I trust you, fix up this boy, say

Make your own fun, man, no drugs around on Tuesday

Really naughty airhead, making all the men mad [on] Thursday

Don't care about the money spent by Friday

Polari was rife with "she-ing," an academic term that refers to the linguistic practice of feminizing people and things. She-ing appears almost universally and across centuries in gay language, from Peru to the Philippines to South Africa (where gay slang is called Gayle), to Israel (called oxtchit, derived from an Arabic word meaning "my sister"), to Soviet-era Russia. It was initially practical, enabling gay men to talk about sex and lovers in public without fear of arrest or persecution.

"You can she anybody," Baker says. "You can she your father or the police. It's inverting mainstream society's values so that everybody is potentially gay and everybody is potentially feminine."

In the West, the gay lexicon dried up after Stonewall, relatively speaking. But in Putin's Russia, where the environment remains extremely hostile for LGBT people, the website Gay.ru, according to a paper by researcher Stephan Nance, lists a course on how to speak present-day Russian gay, a slang called goluboy -- from a word related to the bluish color of a dove -- presumably to help gay Russians identify one another. The site addresses readers as devachki ("girls"), discusses misgendering, and provides instruction on gay tonal inflections when saying words like "sister" ("sestraaaa!"). Gays in Putin's Russia have also Russo-fied Western terms such as queer ("kvir") and coming out ("kaminaut").

In 1880s St. Petersburg, men cruising for sex with men were called "tetki," or "aunties." (In polite society, they might be said to be getting up to "barskie shalosti," or "gentlemen's mischief.")

Denis Provencher, department head of French and Italian at the University of Arizona, has yet to identify a similar argot as Polari or research into gay-specific slang in French, where discourse, in typical French fashion, operates as more waltz than stride. Recently, however, many of Marcel Proust's personal correspondences came to auction at Sotheby's and revealed he used Latin as a secret code when writing to his lovers.

"The closet is really an American social construction based on a narrative of Judeo-Christian ideology -- death and resurrection," Provencher says. "Coming out of the closet is like being reborn. In French, we are talking about living in good faith and in bad faith, being authentic in society."

The verb assumer is used, he says, and operates beyond talking of one's sexuality.

"When you say, 'je m'assume,' it means, 'I assume my social role.' And in France you would never come home and say, 'Mom and Dad, I'm gay and this is my boyfriend Frank.' You'd say, 'This is Frank and we love each other.' "

Provencher's forthcoming book, Queer Maghrebi French, looks at LGBT North Africans living in France and their relationship to language.

In Arab societies, "the harem is this enclosed space that we think of as a feminine space. The harem is also the house of the father. So if you've 'come out of the harem,' you've come out of the patriarchy. Young North African men use the harem as an analogy of the closet. There's also this analogy of dropping the veil. Women who drop the veil in Western society are seen as sexually progressive," he says. "You also get these strange narratives where men talk about wandering through the city looking for sex, but they're also wandering toward Mecca as well."

While vocabulary might be the most fun part of lavender linguistics for the layperson, scholars are concerned with aspects such as tone, inflection, and gesturing, as well as the political and cultural implications of language -- how the press write about LGBT issues, for example, or how queer people communicate with each other privately and at work, or how gay language is learned.

"All this talk about assimilation and acceptance still requires a certain kind of conformity, and, despite your group that's all in favor of the heteronormative, many same-sex-identified persons are not comfortable with that mold," Leap says. "And so you've got to let off some frustration. You've got to let off a certain amount of steam and anger. And talking gay is one way of doing that."

That raucous gay tongue of yore perseveres most strongly in American drag culture, and, for word lovers today, it might be the only bright spot of innovation. The film Paris Is Burning centers entirely on the lexicon of 1980s drag balls, where terms like "realness," "house," "mother," and "shade" flash on-screen and move the narrative. (Those terms are so mainstream now that, in May, the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign accused the Democratic National Committee of "throwing shade.")

"[The participants on RuPaul's Drag Race] have quite a clever use and attitude toward slang. There's a celebration of language and a joy and a humor which feels like a successor to Polari," says Baker. "Even though it's American."

Online, where most evolution in the lavender lexicon occurs today, one might say there's a bit less joy.

"It's more utilitarian and based around hookup culture when you're typing away on Grindr," Baker says. "Shorter phrases that have more to do with sexual things. Gay people on the Internet don't want to come off as funny or showing these rather creative uses of language. They want to show themselves as being as masculine as possible. There's a sort of performance there."

That performance, like she-ing before, crosses the East/West divide. On hookup apps in Russia, you're bound to see users protesting "bez korony." That means "without a crown," or, in gayspeak, not a queen.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.