In 1984, I was old enough to know that I was gay, and that sex would kill me. I knew that if I kissed another boy in public I could be arrested. My favorite song that year was "Sexcrime (Nineteen Eighty-Four)" by the Eurythmics, and in ways too complicated for me to articulate then, I knew at some deep and cellular level that I was a sexual outlaw and that my desires would be complicated and compromised for decades to come. Perhaps that's why, seeing Call Me by Your Name at a special screening last summer, I was swept up in ways I didn't expect to be: The movie is set in 1983, and is therefore free of the specter of AIDS. It is the least cynical depiction of gay desire I've seen, and the most elegiac, for this was how we dreamt of experiencing love in the 1980s--a fantasy of a world liberated from AIDS and homophobia. Of course, we are not free of those twin scourges even today. When we published Bret Easton Ellis's review online in December, the trolls were not slow to leave their thoughtful contributions:

"How disgusting: pedophile behavior glorified."

"Pedo romance! What next."

"Yup, this movie is very sick."

"Pedophile pandering movie. It's all the rage."

Putting aside the fact that the most common age of consent in U.S. states is 16 (and 14 in Italy, where the movie is set), this hysterical response to a love story illuminates an old calumny that gay men are out to despoil America's children, a narrative that serves as a smoke screen for the myriad ways in which gay youth are the real victims, terrorized by their parents, schools, and communities, into repressing their sexuality, often with tragic consequences. Intentionally or otherwise, CMBYN inhabits a world in which there is no judgment, no moral panic, no marginalization. It shows us the world as it could be, not how it is. But it is true where it matters most, in illuminating the emotional whirlwind of first love. It's affecting precisely because it's so rare to see our love celebrated without caveat.

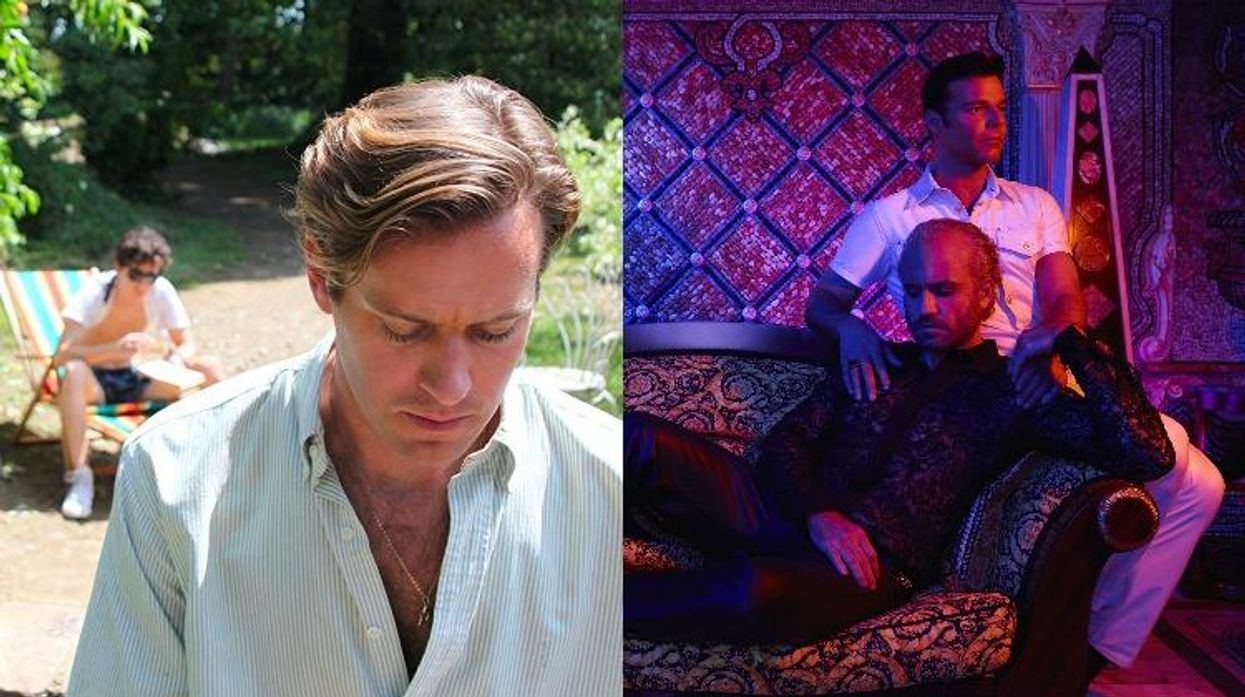

We all have, or deserve to have, our Elio moment. As it happens, I grew up in a quaint English village that was the equivalent of the Italian idyll in which CMBYN is set -- just with less sun, and no Armie Hammer. Like Elio, I was 17 when I first kissed a man -- in a churchyard behind the parish hall one night, drunk and giddy and thrilled by the friction of his stubble, the force of his tongue. Nothing had felt as intense and exciting, nor would again. But kissing and hugging was the beginning and end of it. A few days later I flew to Israel to work on a kibbutz for seven months, and by the time I returned I was firmly in the closet, policing my passions and confiding in no one. That would not change until I was in my 20s and living in Scotland. By then AIDS had unleashed something of a counterattack: We would not be muted and neutered, or so we told ourselves. I was still living there in 1997, when Gianni Versace was murdered, and recall the photos of Princess Diana and Elton John, eyes shiny with tears, at his funeral (a few months later it would be my job to cover Diana's funeral for the newspaper I was then working on).

Yet it hadn't occurred to me until reading Les Fabian Brathwaite's cover story that while money and success helped insulate Versace from the prejudices of wider society, it was homophobia that killed him nonetheless. His murderer, Andrew Cunanan, had been on a three-month killing spree before shooting the fashion designer outside his Miami mansion. Cunanan should never have gotten that far, but his victims were gay, so naturally the police failed to respond with the necessary urgency. Such are the consequences of a society that treats gay sexuality as deviant and criminal.

Attitudes may have softened, though less so if you're transgender, but now is the very time when we need to defend the progress we've made. Policing sex has a long, dark history, and it doesn't take much to reanimate America's obstinate puritanism. For those of us who came of age in the 1980s, the unbridled passion of CMBYN once seemed inconceivable. Let's make sure it never does again.