Photograph by Jason Schmidt

Queer audiences often cite Julianne Moore as one of their female idols of cinema from the last 20 years, and it's one reason she's been featured on the cover of Out magazine (the 2010 Out100, as an LGBT ally). Whether it was her depiction of a woman torn between the demands of the gender roles of her time and her own forbidden desires, many queer audiences have related to the complex and stirring she's taken on over the years. Some just love seeing her cry on camera.

It may seem that Meryl Streep is given an Academy Award nomination every year for her outstanding performances (and they are typically masterful), but the fact that Moore has been overlooked for the past decade until this year for Still Alice (from gay couple Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, who are both co-writers and directors on the project) seems a travesty. Strongly favored to collect the golden statuette this Sunday, Julianne Moore deserves it. Although some complain that it's too little too late, it also means it's also the perfect time to look rich and moving CV of performances to see why she's mattered for generations of moviegoers.

Rather than start chronologically, let's start with Moore's magnetizing presence in Far From Heaven (2002). Unlike the many metallic Bakelite household fixtures that adorn her Connecticut home, Moore's portrayal of homemaker Cathy Whitaker in Todd Haynes's film offers a deep and profound portrait of socio-cultural purgatory in 1950s America. As she moves through her linoleum kitchen and enchants us with her dazzling floral skirts and lame frocks -- a wry recreation of a Douglas Sirk genre piece -- we know Moore's Cathy is beset by a detachment and alienation from the conservative and bourgeois mores of her small town. Especially after she's confronted by her closeted husband's gay love affairs. Moore delivers a spellbinding performance as Cathy, an anachronistic woman lost in the perpetually autumnal seasons of white-picket fence America, living in a town unwilling to accept homosexuality, interracial intimacy, and feminist thinking.

The film captures one of many performances Moore has crafted for her characters around motherhood, gay identity, and social and emotional displacement from one's external reality. We find that with each new performance across Moore's impressive and richly varied filmography, the fine line characters' negotiate between their personal beliefs and those of social is often a very difficult experience.

If we move to Haynes' movie Safe (1995), made almost a decade earlier, we find Moore placed in a muted and paralyzed role. In the post-Chernobyl era of epidemic viruses, bio-warfare, and the compulsive dependence on prescription medication, Safe effectively satirizes not only our obsession with therapeutical culture but also the conventions cultivated by straight white America on maintaining the threat of "contamination." This early standout performance is often overlooked in favor of prioritizing Moore's '50s sanitized housewife in Far From Heaven, but Carol of Safe actually enacts a powerful allegory concerning American angst concerning the HIV/AIDS virus.

For anyone not familiar with the film, Safe tells the story of a 1980s Californian housewife who ostensibly develops a hypersensitivity to chemicals and any prolonged exposure could lead to a deadly ending. In the film, Haynes exploits Moore's appearance -- that ethereal pale skin, auburn hair, and pinkish freckles -- as he makes her the vehicle to channel this allegory. Moore instantiates an innocent obliviousness and her willingness to accept the teachings on chemicals and contamination from a HIV-positive cult leader accentuates the film's interest in sickness.

Carol, as the privileged white American woman, becomes the perfect site for Haynes to localize -- and indeed ironize -- the panic that ravaged America during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s (the film is set in 1987). As a mother, Carol is the bearer of life and offers us a future life through her children and her enduring maternity. Should Carol get sick and be incurably unwell, then we have reason to panic: the life force of our world is now under threat. Thus Safe encapsulates not only an obsession with the medicinal that the HIV/AIDS crisis compounded but also around issues of disease and whose lives do we mourn and whose do we not.

Moore's cinematic association with the suburban -- and its exhausting and alienating elements for anyone slightly different from straight, white domesticity -- is undeniable. Not only do films like Far From Heaven and Safe explore the destructive potentials the suburbs have on the soul and the psyche, but demonstrate how Moore's association with the suburban mother mean she has become an important star where queer identity, American social-cultural values, and non-normative maternity are embedded.

In many of these complex, nuanced portraits of "women on the verge," we see Julianne Moore's women struggle to cope with the peril modern living often demands. The Hours (2002) sees Moore once more play housewife Laura Brown who is unable to cope with the oppressive social narratives prescribed to her sex, as she takes solace in the stream-of-consciousness ruminations of Virginia Woolf's heroine Mrs. Dalloway in the book of the same name. The film shows an achingly moving relationship Laura shares with her son -- an intimately sacred bond, one often shared between mothers and their queer children -- which also makes The Hours all at once exhausting and exhilarating experience. Seeing the queerness of the young boy fostered and recognised by mother Laura is incredibly touching, as Laura herself struggles with her same-sex urges and her self-destructive impulses to sign-out out of the burdensome demands that being a wife and mother in suburban American can reap.

Even in remade films that rework the original plot to suit our Internet-oriented, image-saturated, online-angst ridden culture, Moore thrives. When Kimberly Peirce was interviewed on the casting of Moore as Carrie's mother Margaret White -- immortalized by Piper Laurie as the abusive and unstable mother in the original -- for her 2013 remake Carrie, Peirce told Out that Moore "tops" Carrie (Chloe Grace Moretz) in the first-half of the film. But as Carrie grows more powerful and incensed she "tops" her mother. Margaret now becomes the "bottom" figure and is eventually killed by Carrie for Margaret's abdication of power: She relinquishes to her daughter and lets Carrie's become the stronger of the two. This language of topping/bottoming sourced from gay male sexual discourses repositions Moore and Moretz in queer terms. Their struggle at the film's end demonstrates how much each is desperate to become/still be the dominant female figure in the house, but also be the one who wants to gain the most power in the relationship and inevitably penetrate (with knives in this instance) the other beyond recognition.

Even with Gus Van Sant's much-reviled version of Psycho (1998), Moore adds a veiled queer energy in her incarnation of Lila Crane, the sister of the missing/murdered Marion Crane at the centre of the story. When Moore first strides into Marion's boyfriend's hardware store with her sickly yellow headphones and matching Walkman (coupled with her unfussy and utilitarian clothing), we know that Lila is a lot gayer than we last remember her from the original film. In the original 1960s version, Hitchcock made hints that Lila was the queer foil to her butchered sister but left them for mostly for subtext. Van Sant's augments these allusions by really stressing the autonomy of Lila, her disinterest in Marion's boyfriend Sam, and her own singular snooping of the Bates's motel and house. She is the one who discovers the dead "mother"; she is the one deciphers the $40,000 figure from the discarded paper; and she is the one who delivers the final blow to Norman Bates (she kicks him in the head after Sam knocks him to the ground) and ends such madness. It is with this lesbian energy, as well as her assertiveness and self-sufficiency that Moore brings is a performance of Lila that (partly) redeems Van Sant's otherwise superfluous remake.

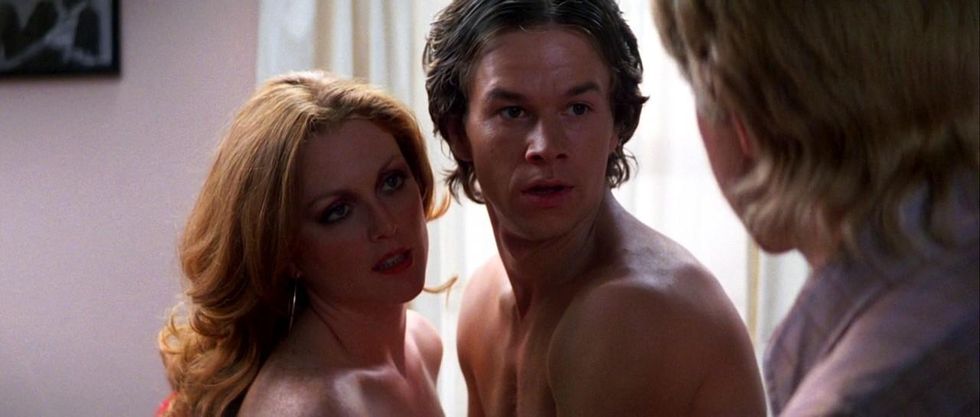

More broadly, Moore is often connected to lost figures that move through their world, mostly using their self-destructive impulses to guide them through life. Boogie Nights (1997) was a huge achievement for Moore. It was the film for which she received her first Oscar nomination, and it garnered her more mainstream popularity for her portrayal of Amber Waves, the part-time girlfriend of porn filmmaker Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds). Amber's struggles with drugs, relationships, and motherhood all enrich the decadent and sex-fuelled narcissism shown in the film and its flared-jeans representation of the Deep Throat '70s porn industry.

But what is the point of reading "queerly" into many of the performances of Julianne Moore? Whether it is her self-pity and heartache in A Single Man (2009) or the unapologetic nudity and emotional depth she delivers in Robert Altman's Short Cuts (1993), or the mainstream lesbian mother she played opposite Annette Bening in The Kids Are All Right (2010), Moore's catalogue of roles offer engrossing accounts of nontraditional, complex, and powerfully self-aware women. These women attempt to transcend unendurable worlds and the misguided social and political narratives society sets. Moore energized the Hollywood screen in the early 2000s with moving, emotionally sophisticated, and arrestingly believable characters damned by their milieu, where introspection and self-destructiveness offer brief reprieve.

Moore has also been a mother figure to others outside the gay community. Her successful children's book series, Freckleface Strawberry, has topped the New York Times Bestseller charts for weeks at a time and become an incredibly popular choice for children for their bedtime reading (and for anyone with freckles, no matter their age).

It is true we can pull apart many other film performances made by the Oscar-nominated actress and revise many of the meanings available in her renderings of emotionally troubled women across her back-catalogue. But in the end, Moore's importance for queer audiences in modern cinema remains undeniable as the many performances she has provided us with on screen attest to the importance of queer characters in Hollywood cinema as a whole. Julianne Moore demonstrates the necessity of having women with self-awareness, emotional depth, and queer identity onscreen -- and we know it will continue for years to come.

Nathan Smith is a journalism student at the University of Melbourne Australia with published writing in Out, Salon, and TheAdvocate.com. Nathan tweets @nathansmithr and maintains a website at NathanRSmith.org.