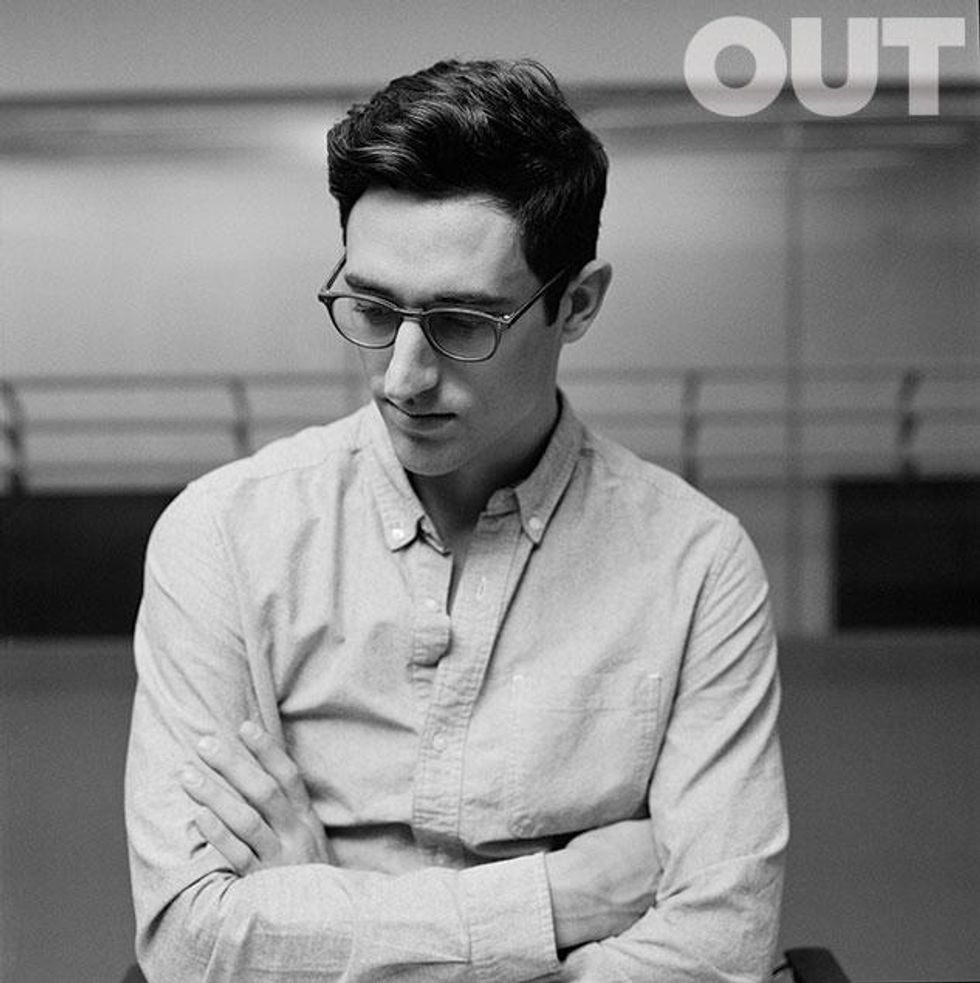

Justin Peck, ballet’s quiet storm

February 02 2015 10:00 AM EST

December 21 2015 4:29 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Justin Peck, ballet’s quiet storm

Photography by Sam Evans-Butler | Shot at the New York City Ballet studio at Lincoln Center

There's a moment in director Jody Lee Lipes's new documentary, Ballet 422 (in theaters Feb. 6), that crystallizes the alluring paradox of its subject, Justin Peck. The dancer has choreographed a piece for the New York City Ballet titled Paz de la Jolla and, inspired by his childhood in San Diego, has decided to dress his male dancers in tiny pastel shorts. "It's a lot of look," his costume designer says, visibly concerned by the pieces, which read less "classical dance" and more "gay Easter Parade." Peck isn't flustered, though. He receives the critique, considers it, and opts to stick with his cerulean hot pants. He's so polite and poised that you'd hardly know he's in the middle of producing a high-profile work of art.

Such is the modus operandi of NYCB's most exciting wunderkind, who at only 27 is both a soloist and the company's resident choreographer. Peck's performances are startling, unexpected, and bold, but he himself seems incapable of losing his cool. Throughout the movie, which charts the roughly two-month stretch Peck was given to prepare Paz de la Jolla for its premiere, he's consistently watchful, centered, and composed, whether he's pep-talking sluggish musicians or gearing up to take the stage.

"I think this is an honest depiction of what goes into making a ballet," says Peck, sitting in a lounge at Manhattan's Lincoln Center, where one of his rehearsal studios is located. "There are a lot of quiet moments captured, which are a big part of the process." In person, Peck is just as introspective--friendly, but also radiating the stillness of someone who's never saying everything. When he's pondering a question, his fingers play the air like an invisible piano, responding to music that only he can hear.

And yet that introspection leads to artistic explosions. Peck seems endlessly capable of pushing his collaborators further than they expected. The New York Times critic Alastair Macaulay wrote that Peck "has a wonderfully unbuttoning effect on his cast." That's partly because Peck knows them so well--he's been dancing with some of them since he joined NYCB's training school at the age of 15--and partly because he's known as an open-minded visionary who'll solicit their input. In that kind of environment, artists are more likely to take chances.

The same goes for rock stars. Indie-folk troubadour Sufjan Stevens has said he didn't like or understand ballet until Peck convinced him they should work together. He had such a good experience collaborating with Peck on 2012's Year of the Rabbit, which used his existing music, that he wrote an entirely new score for their next project, last year's Everywhere We Go.

Partnerships like these underline why Peck's output has been so thrilling. Though he's steeped in tradition, he's not afraid to leap into uncharted terrain.

We can see that balance in Ballet 422. During a section of

Paz de la Jolla, the entire ensemble moves in unison with familiar-looking ballet steps, but then two dancers suddenly collapse to the floor. Are they playing dead? Asleep? The rest of the company rushes to stand over them, arms jutting out at strange angles, and it's as though they've become a grove of trees, protecting the dancers on the floor, or perhaps have morphed into some sort of modernist sculpture. The outcome is spellbinding.

Of course, riskiness means occasionally leaving audiences behind. Though he praised Everywhere We Go, Macaulay said the structurally ambitious piece, with its quick transitions between complex moves and images, felt "too showy" and like "12 different ballets in one."

Peck is unfazed. "I enjoy it when reactions are divided," he says. "It keeps the conversation going."

To align with this month's premiere of Ballet 422, NYCB will mount Peck's new spin on Rodeo, the Americana ballet that launched Agnes de Mille's career in 1942. He's ignoring her lassos-'n'-ranchers choreography to completely reinterpret Aaron Copland's vibrant score. "I think the cowboy theme is a little cheesy," he says. After that, he wants to tackle a story-driven piece or a "tutu ballet." Regardless of how Peck explodes those genres, he'll gently convince us he's making the right call.

Ballet 422 is in theaters Feb. 6. Watch the trailer below:

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!