When I moved to New York in September of 2017, I spent my first month here woefully unemployed, unsure of just about everything except my sexuality. I was 23 and fresh off four years abroad -- and only two years out of the closet as a lesbian. That summer stretched itself into October, its opaque heat throbbing through the streets like a migraine. I dipped my toe, however cautiously, into the city's lesbian history and social circles, trying to get some sense of where the dykes were these days and what they were up to.

Lesbian was a word I'd just come to embrace for myself. Growing up, I'd investigated it with stuttering gestures typical of our generation: covert Google searches, defunct TV shows with their paltry four-episode arcs, and the endless "wax on, wax off" motions of Instagram and dating apps. I had little conception of my own body, nonetheless a shared "lesbian body" -- one in service of work or pleasure.

I took long walks, to make use of my time or perhaps simply kill it. I visited the Leslie Lohman Museum downtown where they were hosting an exhibit called "Evidentiary Bodies 2" -- a collection of work by Barbara Hammer, the lesbian experimental filmmaker who passed away on Saturday at 79. The exhibit contextualized Hammer's creative process with paintings, drawings, video clips and archival materials. I walked through it alone, one of just a few people in the gallery on a Tuesday morning.

Hammer was a familiar name, though I knew little about her. Picking up the exhibition pamphlet, I was drawn to the film titles. In 2015, Hammer released a documentary about the life and lovers of lesbian poet Elizabeth Bishop entitled Welcome to this House. Six years prior, Hammer's experimental style, which had so defined her work and reputation as a queer filmmaker, re-emerged in A Horse is Not a Metaphor. In that film, Hammer was three years into a battle with ovarian cancer, readying herself for a horse-riding stint in New Mexico at Georgia O'Keefe's Ghost Ranch, all while receiving regular chemotherapy treatment. In her artist's statement for the project, Hammer described not a degeneration from cancer, but a bodily reappraisal: "Freedom is riding my horse on a trail exploring the unknown or seeing with the eyes that rebirth from cancer has given me, as the world becomes new again."

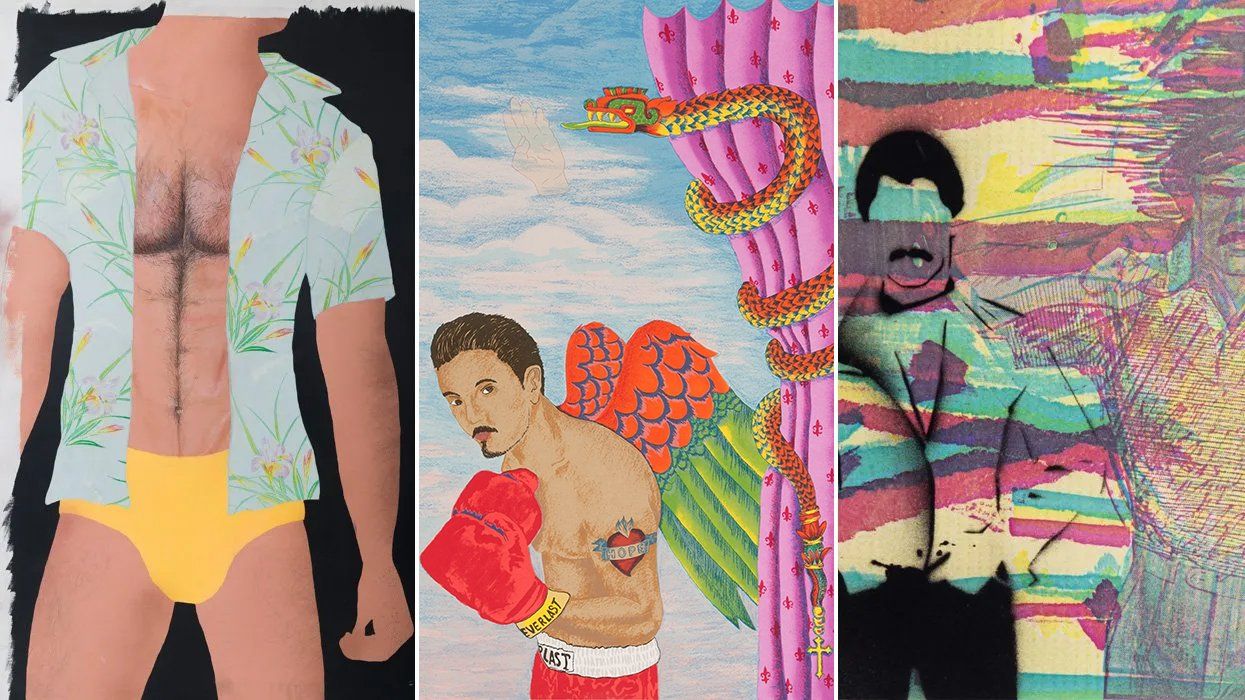

Upon viewing the work, I felt part of some previously invisible throng -- bodies interlocked and informing each other's silhouettes, moods, and idiosyncrasies. Hammer's work was revelatory in its embrace of the lesbian as spectator and participant, object and voyeur. When one is young and closeted, there is an implicit threat to looking. We avert our eyes, train them downward lest they wander where not welcome. Hammer's early films, Dyketactics (1974) or Superdyke Meets Madame X (1975) do more than just document lesbian bodies: they elevate them, blend them seamlessly into surprising environments, bestowing upon them staggering power. In Multiple Orgasm (1976), the female climax becomes a geological event, the skin and fluids one with the ongoing erosion and formation of mountains. In Hammer's films, lesbians are expansive -- their intimacies sewn into the grandiosities of the earth. There is honesty to her work, but not one that resorts to strict realism. Limbs, organs, sinewy muscle -- their contortions are allowed to be flamboyant and expressive.

Hammer's camera saw the lesbian -- herself, her lovers, her friends -- as an ecosystem unto itself. In her films, lesbians kiss, screw, and talk. They walk, work, and laze about. Women speak or are silent to equally potent effect. Our gestures are not veiled, our sex is not in service of some other audience. Women simply exist on the other end of Hammer's camera in all their most literal and fantastical forms, readymade for an explicitly lesbian audience.

So often, mainstream representations of lesbian sexuality are glossy and choreographed to the point of tedium. From those representations, a gulf is formed across which the lesbian viewer has no choice but to cling to a facsimile of their life, an uneasy reference point better than none at all. The "lesbian" image, perfected in the heterosexual eye, is a kind of barrier -- however stylized -- which numbs and belittles the reality that Hammer captured so clearly: our bodies are tools of identity, in motion or stasis. We are lesbians because of these bodies, not in spite of them, and because of how they bring us into the orbit of other women.

Hammer's vision is sure to endure. As our communications become more fractured, our language more fluid, and our gestures more digitized than ever, the tactility of her work will offer all too necessary grounding. Of course, we'll also always treasure the woman behind the camera (and often in front of it) as well: her humor, her beautiful relationship with her partner Florrie Burke, her activism. What a gift to have come across her films when I did, at a crux in my life where the subject of my own body was finally demanding a conversation.

Ultimately, the horse was not a metaphor -- and neither was the lesbian. I walked out of the white gallery that morning into the glare of another hot day in a city I hardly knew. Now, when I find myself falling too deeply into a digital bender, I turn to Hammer's films, take another one of those walks, and remember that -- all lingo and posturing aside -- I should be grateful for the lesbian body that I'm in. For that and for everything, Barbara, I will always be grateful.