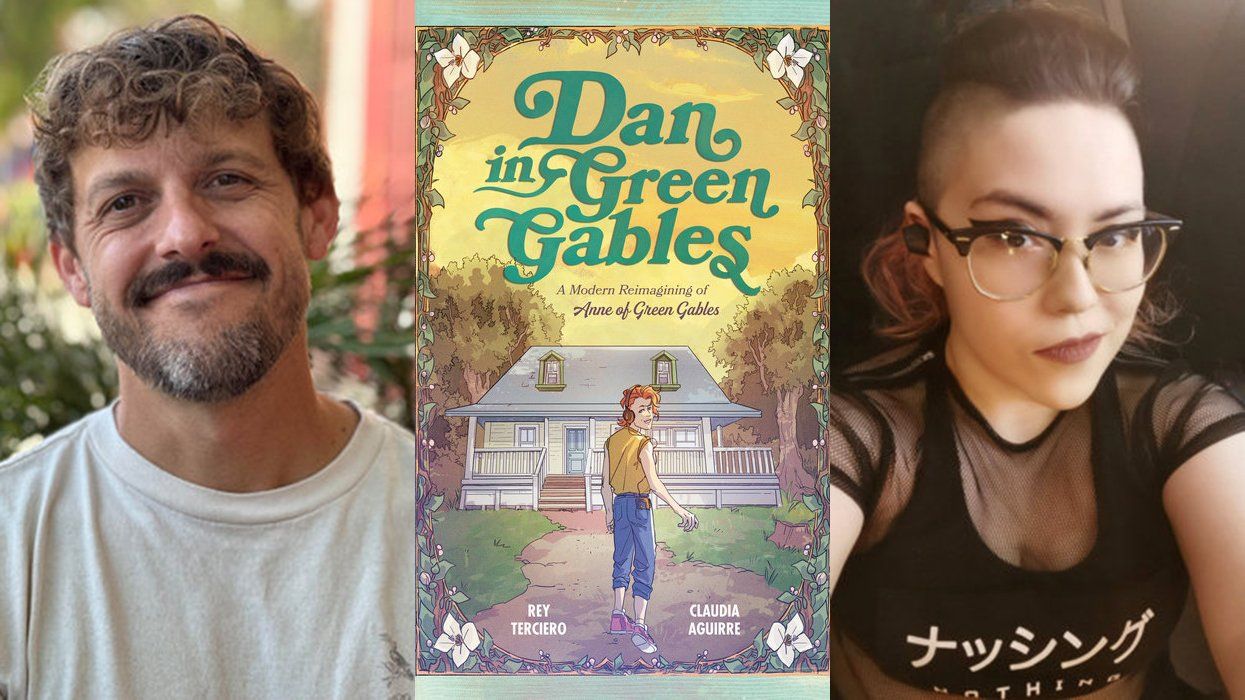

Illustration by Aude Van Ryn

Excerpted from Visions and Revisions, published by Soho Press.

I was a foot soldier in an army small enough that the generals and the grunts were in daily contact with each other -- at its peak, there were perhaps a thousand people at ACT UP's Monday-night meetings, and only one or two actions a year managed to get even half that many people on the streets. I'd say I was the equivalent of cannon fodder, but that'd push the metaphor into an uncomfortable place -- the truth is, I had a better chance of surviving this war than far too many of my peers. Like a centurion quaking when Caesar inspected the ranks, I stammered in the presence of Larry Kramer -- the only man I have ever known whom I consider a hero -- and felt blessed, anointed even, when he deigned to know my name. I make no claims for my time in ACT UP (or Queer Nation, or Pink Panthers, or WHAM!, or any of the other offshoots and unofficially affiliated groups that sprang up in the early '90s). I wasn't a founder or a leader. I had no ideas, did no heavy lifting, acquired no specialized knowledge, took no extreme risks, committed no felonies in the name of civil disobedience (I was arrested three times, spent perhaps 12 hours total in jail, another couple in court; in all three instances I received an ACD, or adjournment in contemplation of dismissal, which is the judicial equivalent of a slap on the wrist, except there's no slap). All I did was give 30 or so hours of my time each week: in meetings and marches; at actions and demos; working phone trees; xeroxing and stapling flyers; assembling bleach kits for addicts to clean their works and exchanging new needles for used ones; patrolling the streets of the West Village to deter gay bashers. And I educated myself: For three or four years I read almost nothing that hadn't been published in the previous decade or been written by a gay man or lesbian or bisexual or transgender person -- everything else lacked urgency to me, seemed so divorced from the present moment as to lack all meaning in a world that was being remade before my eyes, by a disease, and by the people fighting it. I was a body and a voice and, for the first and last time in my life, an unconflicted believer. If I go to my grave thinking that I never did anything more important than what I did in ACT UP when I was 22 and 23 and 24 years old -- and so far nothing has come close -- I will go to my grave happy, and proud.

When I think back to those days I think of Bob Rafsky (whose shattering eulogy at Mark Fisher's public funeral was resurrected in David France's How to Survive a Plague), gently coming on to me and then rejecting himself on my behalf so graciously that I felt like a better person. I think of a man I met at a porn theater known variously as the Bijou, Bijou 82, or Club 82. We fooled around for a bit but the chemistry was off, and as I excused myself from the booth he asked me slowly, in a thick Eastern European accent, "Are you HIV-positive, or HIV-negative?" I told him I was negative, and he gave me a nod that only a Slav could have pulled off without seeming creepy. "You're the lucky one," he said. My roommate put that on my 30th birthday cake a few months later. But above all I remember Derek Link. Of all the things I could tell you about him, the most relevant is that he was the first person I slept with who told me he was HIV-positive. He told me the night after we met, which is to say, the night after we had sex for the first time. That had been a Thursday, and I decided to skip work on Friday to hang out with him. We went out for breakfast at the old Odessa (I had French toast, he had pancakes). He said he had something to tell me and even as I guessed from his tone what it was he said: "I'm positive." I use quotation marks here because I know these were his actual words: I recorded them on a piece of yellow paper ripped from a legal pad that I later tucked into a new journal. I was a sporadic journaler at best, usually starting one when I felt that something momentous had happened, and I knew that something momentous had happened here. Not that I had slept with an HIV-positive person, but that I had met someone great. Someone about whom I need manufacture none of my usual illusions to love. I already knew from ACT UP that Derek was a member of the inner circle of the Treatment and Data Committee, and that alone would have elevated him into an exalted position in my estimation. But it was what he had done before joining ACT UP that cemented my feelings for him. Or, rather, what had been done to him, because Derek, like me, had been a witness, a cog in a brutal adult machine, but unlike me he had not escaped unscathed -- he had been gnashed and ground and all but chewed up in the machine's gears. So great was the psychic torment inflicted on him, and so complete was my identification with him, that 10 days after I met him I wrote in my new journal: "I know that I will write about us." We only hooked up for a few weeks but months later I was still writing, not because I was carrying the torch but because I was convinced that Derek was "a more authentic version of myself."

From that same journal, in an entry dated January 20, 1991:

I haven't been really writing down what I know about Derek. I've concentrated instead on how I feel about him, and trusted that the mundane facts will remain in my memory. I feel a little guilty just contemplating reducing Derek to a list of historical facts that would begin: b. May 30, 1967; and therefore suggest the ending: d. _____, and I don't really want to think about how soon that date may come. But, for the record:

DEREK LINK

* b. May 30, 1967

* HIV diagnosis: sometime in the summer of '89, since he found out 2 months after graduating college when his best friend/sometime (or onetime) lover, Stephen, was diagnosed with PCP.

* Education: 7 years in English boarding school (11-18); 2 1/2 @ Columbia, finishing up at Bard. BA in, I think, Art.

* Sex: Btw. 450-500 men. For the last 2 years, 50 men a year. Before that, 100. Likes bathhouses. Loves getting fucked, having cum on his face/in his mouth. Tells of groups of 8 or so boarding school kids taking turns tying one another to a wire box-spring and gang-banging the victim. Sexually active since 14. Out since 16.

* Before AIDS: Painting was his passion. I've never seen one. He doesn't have space or time for it now. Sculpture, though, and architecture, are his 2 favorite art forms, though he doesn't practice them, because they are 3-D, and therefore a tangible, unavoidable part of reality. He also played in an all-gay boy hardcore band (w/ Stephen).

* He was bashed in Boston in '89. He could've died; his lungs filled up with blood. 4 boys beat him with sticks. None saw jail. He was awarded $20,000 in damages to be paid in installments. The 1st is 2 months late.

* Some work: He gave private art lessons to rich kids. $65/hour, 10 kids a week. Also painted their portraits: $5,000 a pop. A lot of this money paid for Stephen's health care. He's got plenty in the bank too.

* Family: Jewish (changed name from Linkowitz). Father's side has big $. Great-uncle converted to Catholicism and endowed the George Link Pavilion in St. Vincent's. Dad sits on the board of some big company.

His mother, he told me the second day we were together, had been a Holocaust refugee, fleeing Germany as a little girl and taking up residence in England. She moved to the States and married Derek's father, who was a businessman based in Chicago, while Mrs. Link taught French at Tulane. It was a stuffy family dynamic. Derek was mostly raised by nannies and only saw his mother an hour a day, right before bedtime -- from an early age she insisted he only speak to her in French so that he would learn the language. His father came to New Orleans on the weekends, and the family had at least one formal meal together, served by the maid. Derek recounted his week during soup or salad, his mother during the main course, his father during dessert and coffee (to this day, Derek told me, the sight of a waiter approaching the table to clear it makes him talk faster). Boarding school in England seemed like an idyll at first, Lord of the Flies meets the video for "Total Eclipse of the Heart," but at 15 or 16 or maybe 17 Derek had what was in effect a nervous breakdown, and eventually refused to leave his room. The school contacted his parents but they refused to come get their son, and after it became clear that they weren't bluffing the school had no choice but to put Derek in a mental institution, where, doped up on Thorazine, he lingered for nine months. Eventually Derek's maternal grandmother, who still lived in England, took him in, but Derek ran away and soon enough was hustling on the streets of London, which was probably when he was infected. After a year and a half of this he sent a set of faked A levels to Columbia University and, when he was admitted, guilted his parents into paying for it. He did two and a half years at Columbia, then transferred to Bard, where he began hustling again, and after he graduated he moved to Boston to pursue a painting career. He'd had two solo shows and one group exhibition, or one solo show and two group exhibitions, and played in a punk band with three other gay boys, all of whom were fucking one another without condoms, when one of them, Stephen, was admitted to the hospital with pneumocystis pneumonia. The other members of the band got tested, which is when Derek found out he was positive. After Stephen got out of the hospital, Derek took him to the gay bars in the South End, and on their way home they were bashed by the group of boys mentioned above. Stephen was still weak, and to give him a chance to get away Derek threw himself at the attackers, and ended up so badly beaten that he had to be hospitalized for two months, with, among other things, a collapsed lung. Stephen died less than two years after he first fell ill, at which point Derek gave up painting to become a full-time activist.

He still carried Stephen's driver's license at the time we met. I saw it. I held it in my hands. I noted the familial resemblance between Stephen and Derek and the gleam that came into his voice when he looked at the picture, which makes it that much harder for me to believe that everything I've just told you is a lie. The Judaism -- the Holocaust -- the move to England and the nervous breakdown, the time spent in a mental institution and hustling on the streets, and above all the HIV infection: Every last detail -- save, perhaps, his name -- was a fabrication, invented for who knows what reason and perpetuated with some major or minor variations not just with me but with all of ACT UP, right down to a supposed outbreak of Kaposi's sarcoma -- on his genitals, so that he wouldn't have to show anyone. Yet despite the enormous psychic energy it must have taken to maintain this pose for, what, five years? Seven? Derek was also one of the nine or 10 most important AIDS activists in the United States. He smuggled unapproved medications into the country for PWA buyers clubs, discovered $50 million in unspent federal money that was subsequently poured into AIDS research, and, after taking a job at Gay Men's Health Crisis, became one of the chief lobbyists and architects for what eventually became ADAP, the AIDS Drug Assistance Program, without which tens of thousands of New Yorkers, including many of my friends, could not afford their meds.

I say he did all these things despite the energy it must have taken to maintain his assumed identity, although I wonder if it should be because. Because no matter how urgent the task, the kind of work that Derek and the other members of T&D and TAG (Treatment Action Group) did was, from any rational point of view, impossible. They were artists mostly, a few guppies, a few people like Derek too young to be anything yet. None of them had a medical background, and while they were trying to earn a living and trying to stay alive they were also giving themselves a crash course in virology and epidemiology and bureaucracy at the city, state, national, and international levels, and while they were educating themselves they were also taking on doctors, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies, the New York Stock Exchange and the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases and the Centers for Disease Control and the House of Representatives and the Senate and three successive presidents, and, with the help of a few thousand legmen, they won. They changed the way AIDS was talked about, the way it was studied, and, most importantly, the way it was treated, and they did it all without giving in to despair or anomie, to the crazy-making frustration that any engagement with the health care bureaucracy is bound to engender, although in their case the frustration was magnified to an existential level and manifested itself as terror and rage. And they didn't give in to that terror either, or the rage. David Wojnarowicz's fantasy of shooting politicians with syringes filled with HIV-positive blood remained a fantasy, though whether that fantasy was a greater goad to politicians or AIDS activists is hard to say.

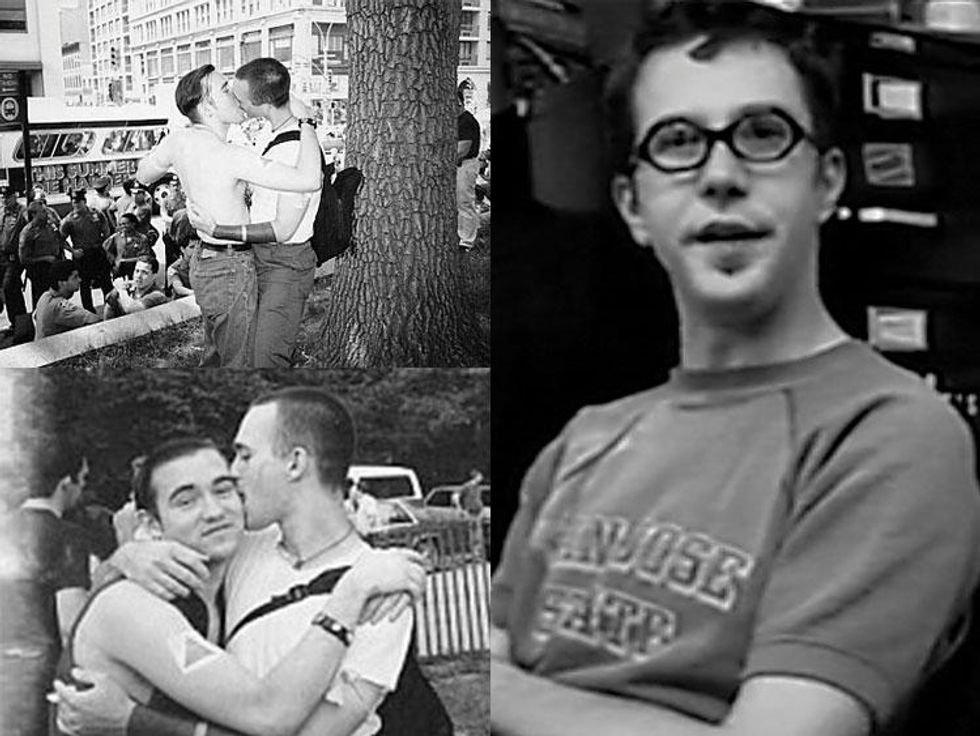

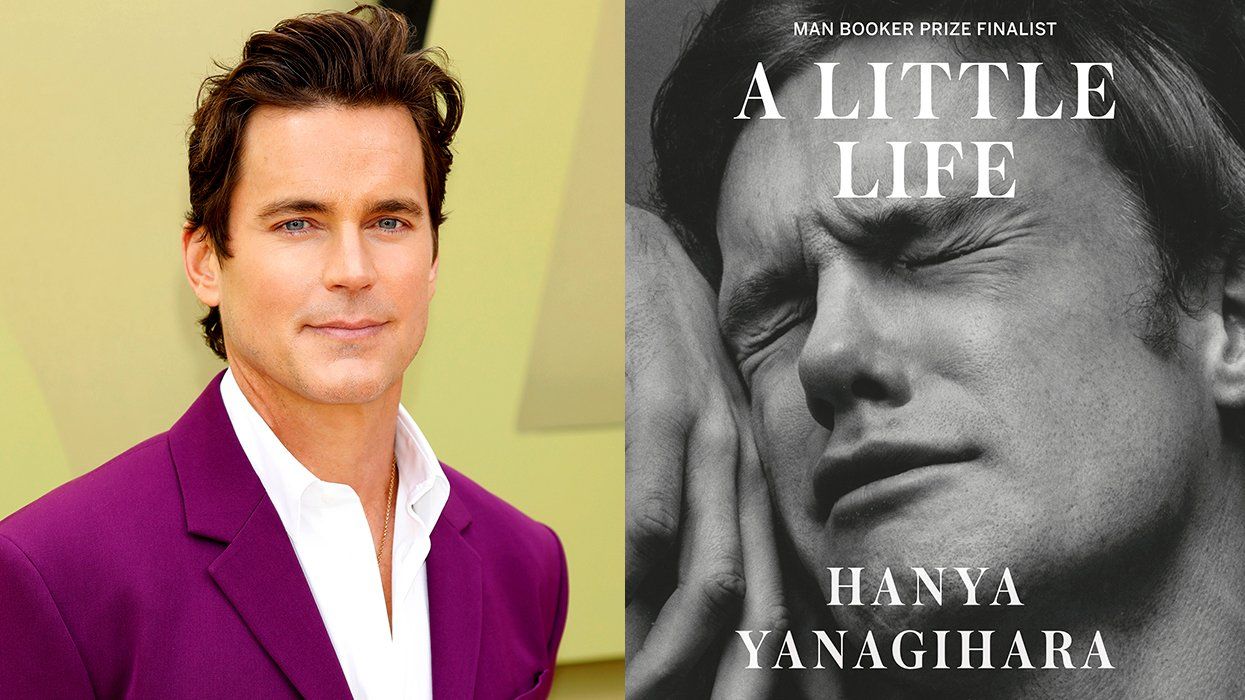

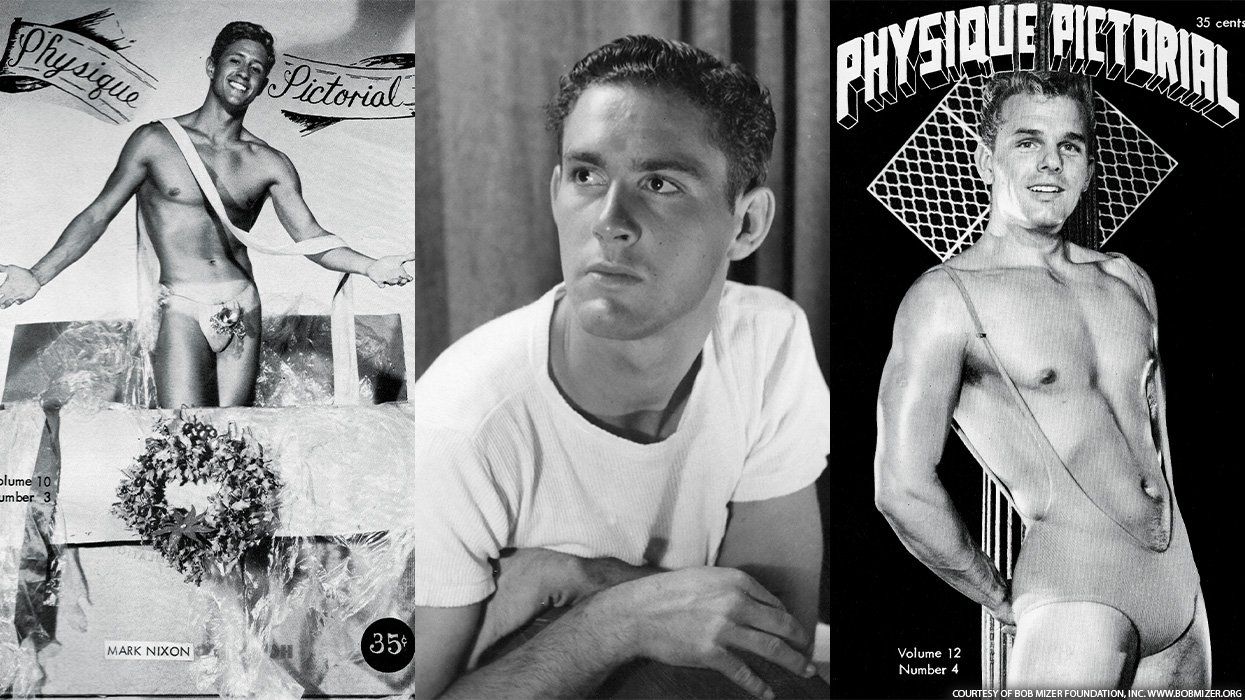

Left: Dale Peck makes out with men; right: Derek Link shown in David France's film, How to Survive a Plague

To suggest, however, that most of the members of T&D and TAG did what they did because they were HIV-positive is to forget that thousands upon thousands of HIV-positive people, many of whom were financially or educationally better suited for the task, did not fight in the same way, or at all. What I mean is, I don't believe it was empirically necessary for Derek to adopt the identity of an HIV-positive person in order to become the kind of AIDS activist he became. But he did, and he immersed himself in his role to such a degree that he put himself at risk of actually seroconverting. One of the great pleasures of our sex was that I didn't have to take my dick out of his mouth before I came, could let go of that last little piece of self-consciousness that safe sex requires and immerse myself, in all senses of the word, in sexual abandon, and not come back to the real world until the sound of Derek slurping up the last drops of my jizz reached my ears. I don't know if he also engaged in unprotected anal intercourse, but the fact that he was willing to let a stranger come in his mouth suggests the degree to which he had subsumed himself in his adopted identity. Suggests that there was a deeper process of self-abnegation and -invention involved, something that went beyond AIDS or sexuality to the inescapable contingency of the self -- of, to use Leo Bersani's term, personhood, the existential status "that the law needs in order to discipline us, and...to protect us." I won't say that Derek wanted to opt out of that discipline, or that protection, but his relationship to it was obviously conflicted, as if he had internalized the "crisis of representation" Simon Watney detailed in Policing Desire and amplified it into an identity -- as if he had come to believe that the only existence that had any meaning during a time of plague was as one of the infected. And though few people would have endorsed this position openly in the years before combination therapy became available, the number of gay men who hurriedly capitulated to HIV after 1996 -- their surrender guided (goaded?) by a new pornographic lexicon of "bug chasers" and "gift givers," the redefinition of "breeder" from a derogatory term for a heterosexual to a heroic name for a man who "gave" his HIV to his partner -- suggests that from the beginning of the epidemic part of the fascination with AIDS was the desire to have it. To live with it? To die from it? I suspect it's probably neither, which is to say, I suspect the HIV these men wanted was the phantasmic kind that brings "meaning" to life rather than sickness or pain or death -- the kind that Derek had in other words, rather than the kind my friend Gordon had, and that killed him in 1996.

Which brings me back to my original question: Did pretending to be HIV-positive help Derek do the work that he did, or was it incidental? I don't know the answer to that question, nor do I know how you'd ascertain it. Certainly not by asking Derek: Why in the world would you believe something a pathological liar told you? What I do know is this: We were walking down East 14th Street one day, either between First and A or A and B (I remember we passed the post office) and I was asking him why he'd stopped painting. There was more than a little uneasiness behind my question, because a part of me considered the time I spent as an activist as time I didn't spend writing, and vice versa. But I was surprised by Derek's answer. Art interfered with a direct experience of the world, Derek told me, and he wanted to experience the world firsthand. I asked him to elaborate and without missing a beat he pointed to a homeless man sleeping on the sidewalk. It was January, and the man was covered by newspapers, and Derek said, Art is like those newspapers. It covers up the real world, and the best that you can hope for is to see something through it. But whatever you see is going to be colored by art. Obscured by it. You're not going to see the real thing. You're going to see the artist's interpretation. Implicit in Derek's notion of art is the idea that it's always representational, of processes and ideas as much as objects and people. Most artists I know accept the idea that mimesis contains a greater or lesser degree of falsity even as its core -- its intention -- remains truthful, but what Derek seemed to be telling me was that, however much truth there is in representation, the intention is always false. To falsify. I didn't want to believe that then and, 23 years later, I still don't want to believe it. But I've always believed it -- have believed it helplessly, which is why I've never even tried to make art that depicts the world as it actually is, but instead try to make art that points out its own biases, its own falseness, and the necessary illusions without which life is impossible. So that, if nothing else, the reader will know that what he's looking at is fiction, not history, and certainly not the world. I believed in 1991, when I was 23 years old, that those two- or three-dozen words were the single most important lesson anyone had ever taught me about the moral stakes of all forms of representation, political as well as aesthetic, and I believe it still. When I wrote in my journal that Derek was "a more authentic version of myself," I believed that he had genuinely endured the horrors, as a child of violence and a gay man in a viciously homophobic society, that I had only witnessed, and I believe it still. I believed that Derek lived his life by a moral code I only made feints at, and even after I found out that the biography he'd presented me was not just false, but malignantly so, in light of the pain his revelation inflicted on those men and women who had loved him, and fought beside him, and in some very real sense died for him, I continued to believe it.

I believe it still.

Excerpted from Visions and Revisions, published by Soho Press.