Ira Sachs's new film Little Men isn't sexy or sentimental in the way you expect a gay coming-of-age movie to be. It avoids strict comparison to Louisa May Alcott's 1871 novel Little Men, a sequel to Alcott's universally popular 1868 "girls' book" Little Women (a gay favorite ever since Katherine Hepburn portrayed Tomboy Jo in Hollywood's 1933 version).

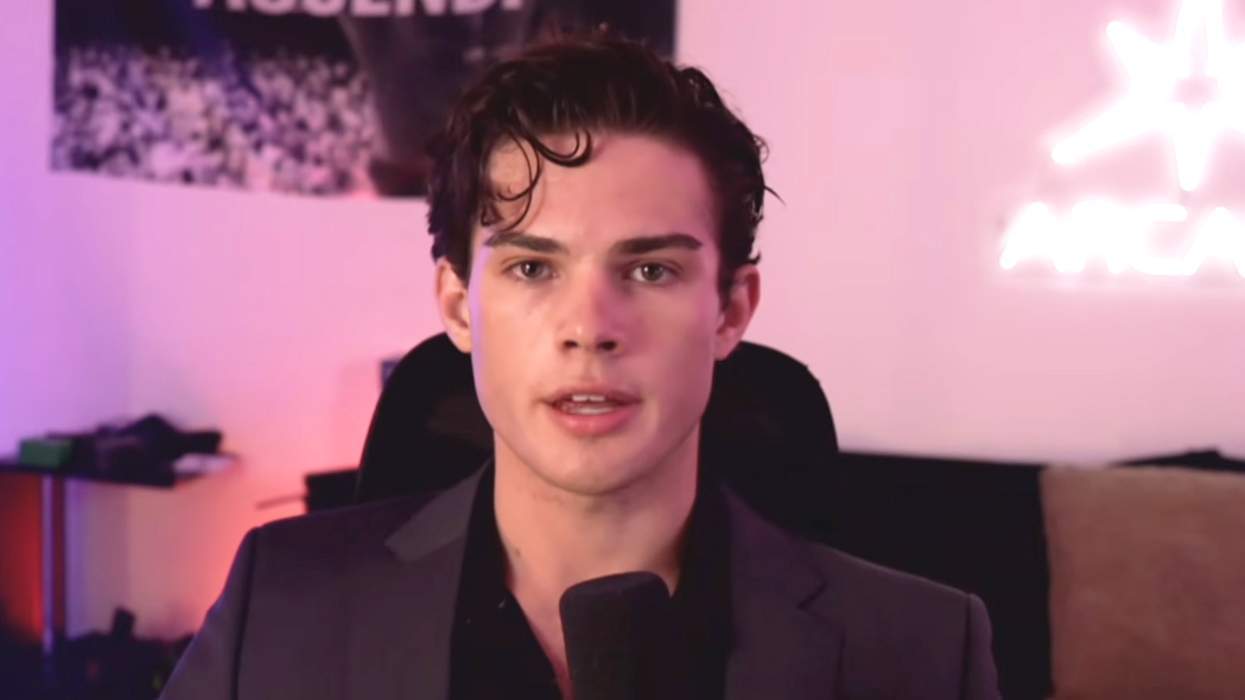

But Sachs' story of the friendship shared by two 13-year-old boys updates Alcott's view of family dynamics and boys' education into the ways of the larger society: Jake (Theo Taplitz) wants to be an artist and Tony (Michael Barbieri) studies acting; both Brooklyn boys dream of attending LaGuardia High School for the Arts in Manhattan. They expect it to nurture their talents but Sachs douses Alcott's schoolhouse premise with the cold water of modern realism. Family pressures influence the boys' relationship in the outside world.

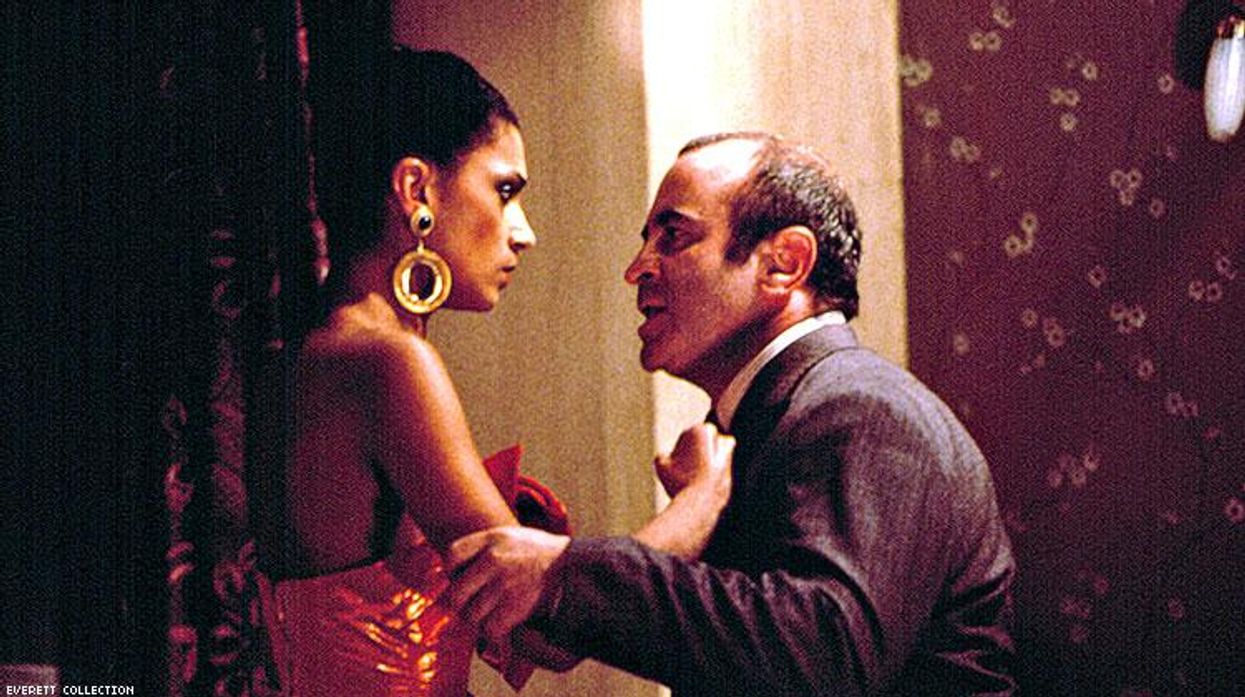

It's obvious that lanky-haired, sensitive Jake will turn out gay and that tough, out-going Tony probably won't. Sachs doesn't venture any further into the mysteries of boyhood affection--he avoids the physicalized emotional bonds that made the story of two orphaned boys in Vittorio DeSica's 1949 Shoeshine just short of erotic and yet so heartbreaking.

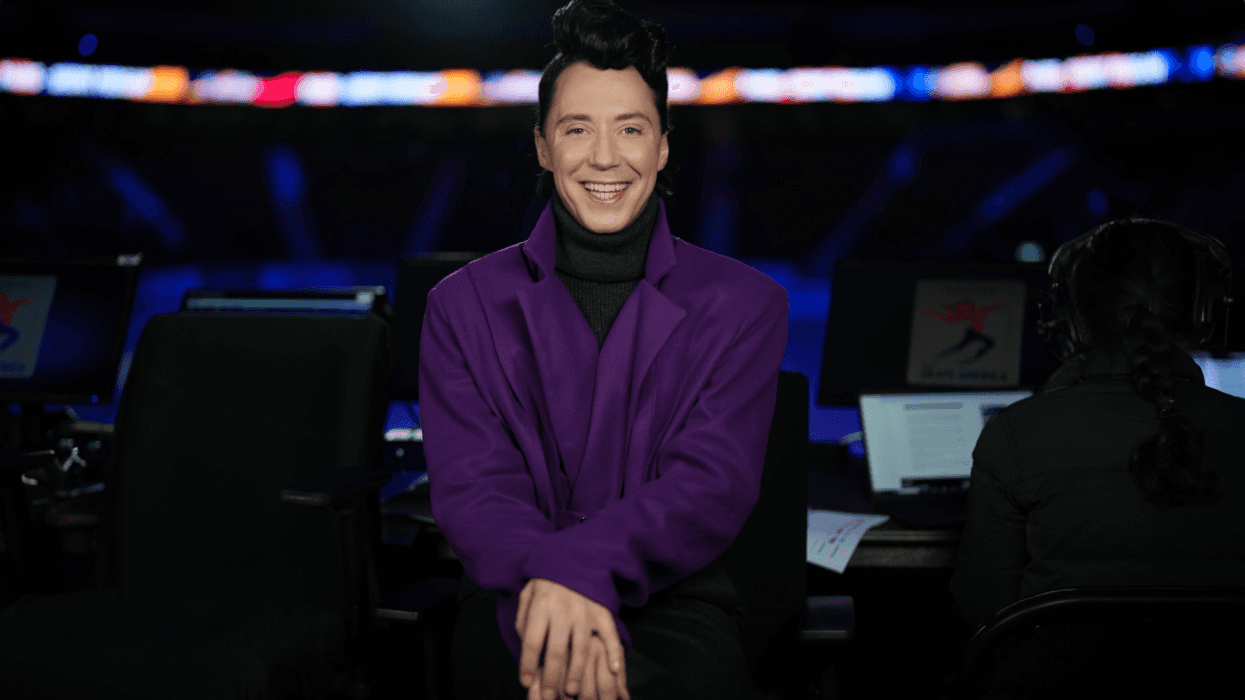

Sachs may be America's most socially-conscious gay filmmaker. He pursues a different sentiment than Victorian-era Alcott, just as he also presents a different Neorealism than DeSica's. He's interested in society's assigned, marginalized, sex roles--whether the hetero infidelities of Married Life, the feminist frustrations of Forty Shades of Blue or the particular kinds of alienation that beset a young gay couple in Keep the Lights On, an older gay couple in Love is Strange and the gay racial outsiders depicted in his masterful debut The Delta.

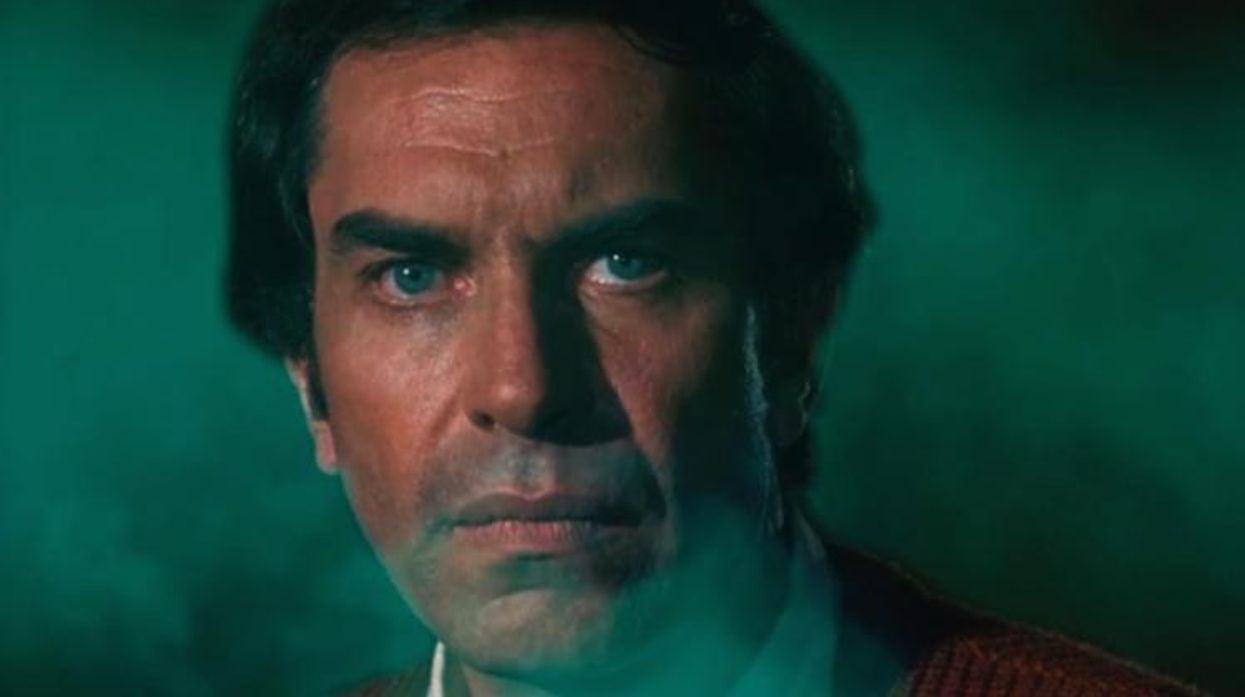

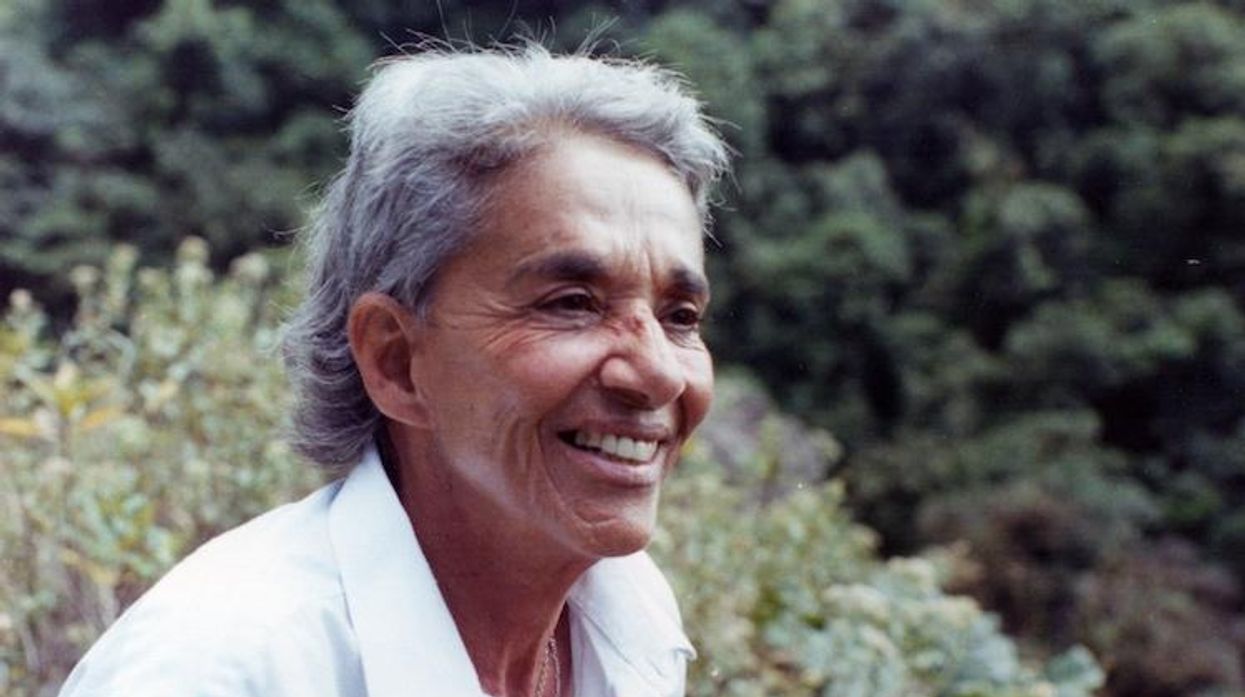

Little Men revisits these themes in its story of atomized family life: Jake's bereaved father (Greg Kinnear) inherits Brooklyn property which erodes relations with a Chilean immigrant who rents retail space and happens to be Tony's mother (Paulina Garcia). This is where Sachs loosens his focus on what makes Jake and Tony alike or different; he settles on examining how the parental characters struggle with economic and class realities.

Sachs makes a disappointing move from the boys' burgeoning social and sexual awareness. A strikingly beautiful teenage girl stays on the story's margins and Jake's petulance is pallid while Tony's acting-class bravado is the film's temperamental highlight. This student-teacher face-off seems improvised and so does the film's plot. Sachs' script (co-written with Mauricio Zacharias) shifts emphasis onto Paulina Garcia's cagey, testy disposition. Her middle-class arrogance and irritability are a sub-theme for Sachs.

Class hypocrisy motivated Sachs' exploration of the closet and the gay underworld in The Delta--which is one of the few truly great indie films of the past quarter century. But lately Sachs' films spend more time indulging middle class foible. Sachs expands his social consciousness beyond the gay ghetto which might itself be a sign of social progress and the ultimate class assimilation. In Little Men this diversion takes the sting out of the first friendships that many gay men experience as first love.

Little Men is playing in select theaters today.