At first The Stanford Prison Experiment gives off a vintage erotica vibe as the actors playing 1970s college students appear wearing period clothes and that decade's particular long-hair and furry faces. Their look -- so out-of-style, it's back in style -- is ingenious. It's a key to the gift that makes Kyle Patrick Alvarez one of the most interesting contemporary gay filmmakers.

Since his very moving 2009 debut film Easier With Practice, Alvarez has specialized in troubled gay men struggling with personal communication. Seeking to understand the sensitivity felt by individuals rather than monolithic social groups, Alvarez gets very close to his actor/characters -- as if to take the temperature of their moods.

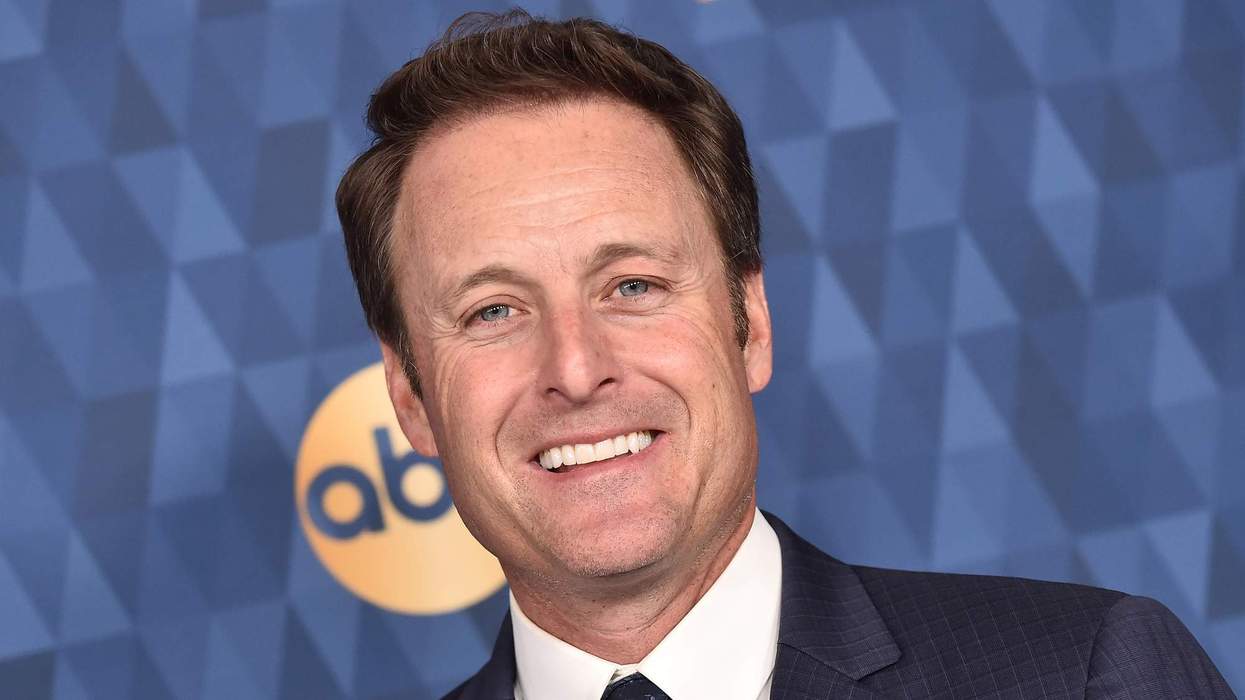

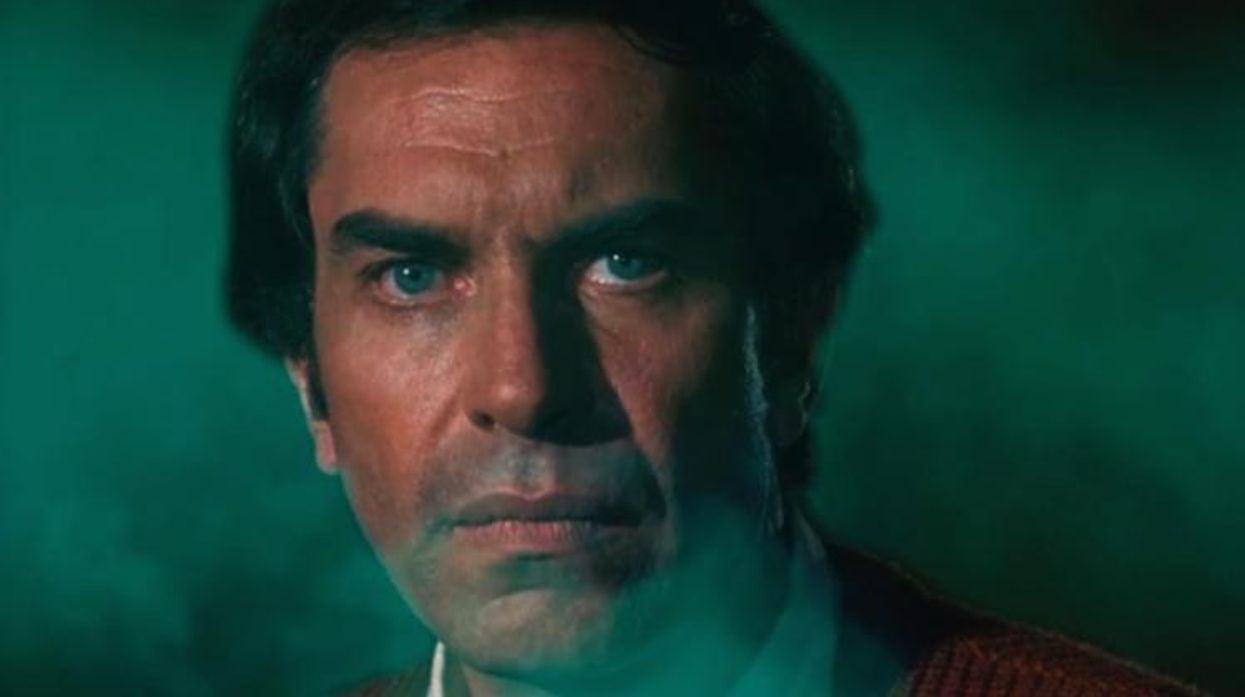

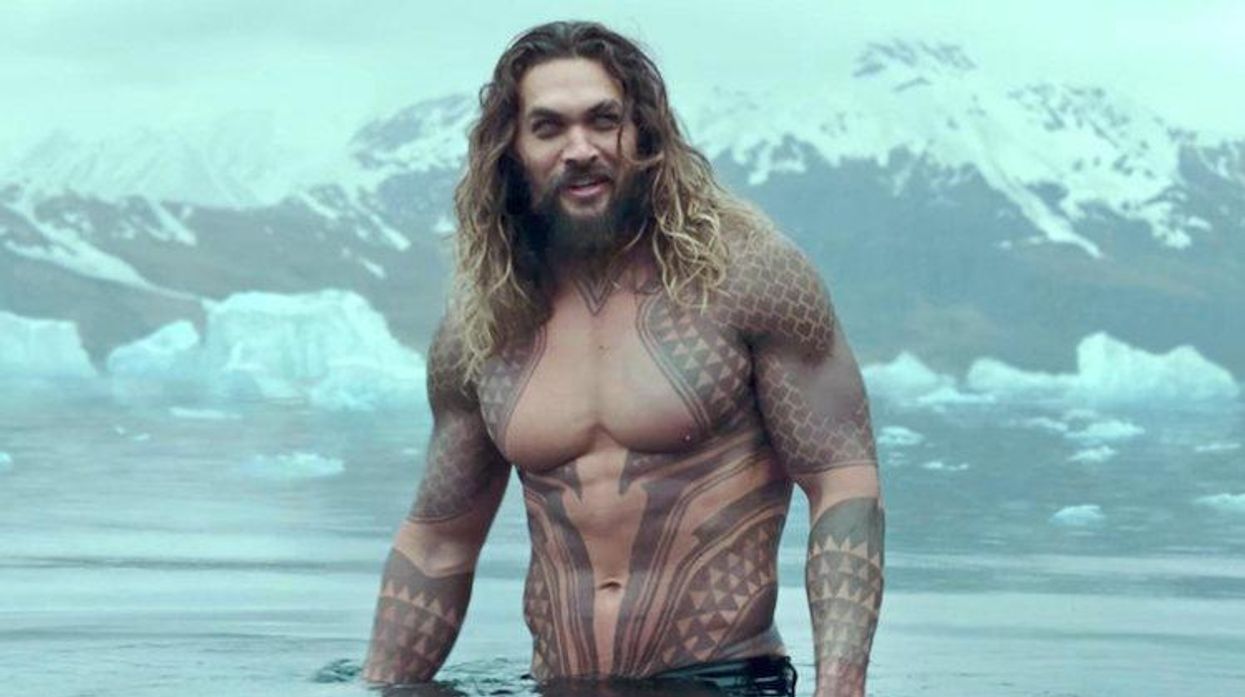

This explains the immediate eroticism of The Stanford Prison Experiment just as it explains Alvarez's interest in the real-life case of an actual 1971 test conducted by Berkeley psychology professor Dr. Philip Zimbardo (played by Billy Crudup, channeling Robert Duvall) who hired students to participate in a two-week trial as prisoners and guards. The premise is like moviemaking, or reality-TV, that gets out of hand.

As fate -- and irony -- would have it, Alvarez loses command of the elements in his control group. The experiment, as it proceeds, dangerously affects its participants; cynicism overwhelms Alvarez' caring approach: The student-guards take their roles too seriously and the student-prisoners collapse into subservience. It becomes Lord of the Flies pessimism, emphasizing the ugliness of human nature.

Thank God Alvarez is not a Kubrick-style misanthrope but this premise seems predetermined to be unnecessarily transgressive and dark -- its lowest point simulates a buggering orgy. It excites the guards and breaks the student-prisoner's morale and self-esteem, while one of them is forced to sing "Amazing Grace."

Alvarez, whose last film starred Jonathan Groff in C.O.G (Child of God), should regret that particular blasphemy against his inherent humanism. Limited by his own conceit (and Tim Talbott's screenplay), Alvarez seems stuck in allegory hell -- as if the point is to show men trapped in the insensitivity of the past, where machismo and homophobia ruled.

But he's got an extraordinary roll-call of young actors who, in the comic book franchise era, rarely get the opportunity to show depth and range: Nicholas Braun, Tye Sheridan, Ezra Miller, Logan Miller, Nelsan Ellis, James Wolk, Ki Hong Lee, and Michael Angarano illustrate the human qualities that distinguish Alvarez among contemporary directors. Of special gay interest is what Alvarez and these actors reveal about the complex code-switching involved in everyday American manhood. Angarano particularly, shifting personality and voice, emotion and strategy, delivers a definitive performance of adult male cunning -- his cagey villainy is worthy of such classic prison films as Brute Force and Short Eyes.

Alvarez never provides a social context for these young men engaging in role-play. He personalizes and eroticizes the past (including the psychosexual implication of this real-life catastrophe) because it gives him a touchstone for universal male behavior. But to simply observe the "psychology of authority and abuse of power" results in a failed experiment. Instead of fetishizing the past, we always need to know how men get their ideas of crime, punishment, virtue, and justice.

The Stanford Prison Experiment opens July 17. Watch the trailer below: