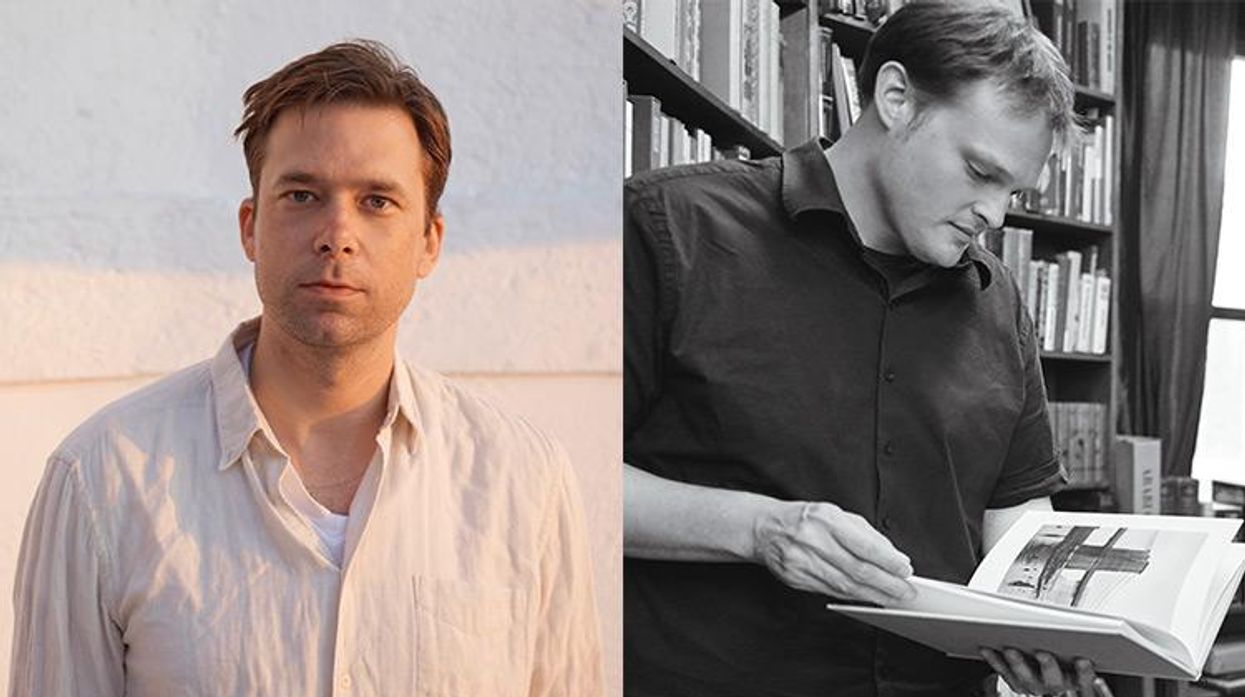

If you're looking for reassurance that LGBT literature is alive and well -- in rude health, in fact -- you could point to any number of titles in the past few years, including Garth Greenwell's luminous debut, What Belongs to You, recently shortlisted for the U.K.'s James Tait Black Prize; Marlon James's garlanded A Brief History of Seven Killings; and the serial award-wining lesbian writer Sarah Waters, who has quietly unpacked queer history with a small canon of exquisite period novels. But it's not just literary fiction that is benefiting from an injection of energy and vitality. Gay poets of color are writing some of America's most electric verses right now, and queer voices are shaking up genre fiction, including Tom Rob Smith, author of Stalin-era page-turner Child 44 and last year's BBC drama London Spy; Richard House, currently working on a sequel to his Booker longlisted espionage novel, The Kills; and Christopher Bollen, who now follows up his gripping thriller Orient with The Destroyers, an elegant and twisting suspense novel that is earning comparisons to the genre's great lesbian doyenne, Patricia Highsmith. Here, Bollen and Greenwell discuss what it means to be a queer writer in 2017.

Christopher Bollen: As a writer I'm fascinated by crime. I'm sure a lot of it comes from the fact that I grew up gay, and that's a crime, or was for a long time. And of course there's a whole history of the detective being gay, or being hard to read, from Sherlock Holmes to Hercule Poirot. They're all slightly ambiguous. There's also the criminal as gay, like Ripley -- a gay man who wants what the straight guy has. I'm so curious, Garth: As a gay man, can you be ruthlessly hard on a gay character and feel like you're not adding to a stereotype?

Garth Greenwell: You can write a great book with a sympathetic protagonist, but there's nothing deadlier to literature than the idea that all we should be doing is exploring lives that flatter our own sense of moral rectitude. I strongly believe that the author's job is not to judge their characters but to see his or her characters in as complex a way as possible. I remember a BBC interview I did with this woman, and her first question was, "After decades in which gay men's lives have been reduced to sex, why would you begin your novel in the bathroom?" Basically she suggested that I was not condemning sex work, and therefore, wasn't I afraid that some gay kid was going to read my book and think, I wanna be a hustler? And I said, "Look, it's not the fact that gay men have sex, or where they have sex, that erodes the dignity of their lives -- it's the homophobic narrative that gay sex is in itself shameful and degrading." Of course I do not want to stigmatize sex work, both as a human being but also as an artist. Why would I want to create a world and then stand in judgment of it? Anytime I feel an author is judging the world he or she has made, I feel like it is a failure of that faculty of looking. Human lives are so complicated that I think they cannot be exhausted by the judgments we make of them.

CB: And I think plots can be easy to describe, but if you can easily describe your character, you're in trouble, because then there's no complexity--it's just a walking cardboard cutout. American literature has a great history of punishing the evildoer or the person who is "wrong." That's not just gay--it's straight too. House of Mirth is a great punishment novel. She gets it for not marrying up as soon as she could. I think that Edmund White was always saying it's so hard to write a gay book for a mass audience because there's not the same sympathy toward a gay character, and there's also a heterosexual dislike of reading about gay sex. I don't know if that's true anymore.

GG: I think it's still the case that books that are focused on queer characters just don't sell as much, and when they do it's a big surprise. But I also think we have to be careful not to exaggerate that. If 2016 taught us one thing, it is that it's not true that books centered on gay characters only have a gay readership. We have to reject the idea that a book is less universal because it is focused on lives that are marked in a certain way by history, class, race, or sexuality. I think for about 20 years it has been allowed to be, to a devastating degree for gay literature, a self-fulfilling prophecy so that there are gay writers who stopped writing those books. They were told so often, "If you write a book that centers on gay lives, you're going to be in a gay ghetto."

CB: We judge books so often on these male heterosexual terms but there actually is a gay sensibility--humor, tragedy, camp. A Room With a View, for example, the film and the book, is steeped in it even though it's a totally heterosexual romance. There's a scene when the men are running around nude. As a kid that meant so much to me, partly because I was allowed to watch it on HBO with my family at four o'clock in the afternoon. It was so exciting. This little bomb was being sneaked into something that was considered high art.

CB: Ed [White] always says there was this great cruising park in downtown Cincinnati, but I didn't know that when I grew up there. I found my identity through books and film and Warhol. I wanted to go to the Factory; I wanted to live in New York.

GG: I discovered cruising when I was maybe 12 in a bathroom at Western Kentucky University, where I would go to summer camp. The bathroom was covered with graffiti, and that graffiti was such an education. And then I started seeking it out. Cherokee Park in Kentucky was notorious and so I went there and found that world. And the second place I got it from was high art, and for me that was books in a kind of haphazard way. I randomly read Confessions of a Mask because I liked the cover, I randomly read Edmund White. But the more systematic high-art instruction I had was opera, because through a series of accidents a teacher at my school discovered I had a voice and started giving me lessons. There's very little explicit gay male content in opera before the second half of the 20th century, and yet it was a great education in how art can be culturally queer without being explicitly queer. One of the things that excites me in recent queer literature, that also pushes against the homogenous narrative about queer life, is this aesthetic that wants to recuperate some of the stigmatized aspects of queer art--things like melodrama, camp, hyper-emotionality--and turn them into a source of beauty. That incredibly resilient, defiant, adversarial, and gorgeous thing that is gay male faggotry is this wonderful resource for art. The way that queer culture can take insult and turn insult into a defiant style is something that really excites me.

CB: Humor is another example of that. Without generalizing that gay people have better senses of humor, I'm just going to put it out there that that might be true, because you have to laugh at yourself first. You have to prepare for the insult and turn it into something else.

GG: God bless these readers who understand that the whole point of literature, I think, is that it's the best technology we have for communicating what another person's life feels like from the inside. And that's one reason why I think there's a kind of moral imperative that we assert and articulate that power of literature, and that we fight against any kind of argument or prophecy about the market that says or assumes that people are only going to read about people that resemble them. If we allow that to be the story that publishing tells about itself, then we have lost the battle that matters. I read books because I want to know what life feels like for people who are not me and for people who don't look like me or have lives very different than mine.

CB: Someone in the book world was saying, "Oh, we're buying books about the poor white American in the Midwest because that's what everyone wants to read about and understand now," and it's like, Oh great, so basically we want to go back to reading more books about white straight men in America. There aren't enough already?

GG: The next novel I'm eager to start working on is about being queer in the middle of America. It's also about the AIDS crisis in rural places. I feel like we're at this really interesting moment of negotiating the narrative of the AIDS crisis for queer people in the '80s and '90s, and yet that story is only told about San Francisco and New York. I want to figure out for myself, and for the book as well, what life was like in rural places.

CB: I feel in a way that being gay is the biggest blessing that ever happened to me, because I probably would have never left Cincinnati, and I probably would have never become a writer. I would have had a nice suburban life, and there's nothing wrong with that life, but I want to kiss whatever gene, or whatever it was, that allowed this because it's enriched life so much, and a lot of it had to do with this outsider feeling, and creating these other communities that were subversive at the time. It does scare me to get rid of all that. With all the pain that comes with it, there is a sense that you can design your own life away from your families, and we don't have to skew towards straight culture. I think that something would be lost if we just heard the narratives of people living in mountain towns raising children, and who are happy.

GG: I do believe that the genuine project of social liberation needs to be the multiplication of models of life that are seen as legitimate. There's no reason in the world why acknowledging the values of these more alternative communities means that we do not also acknowledge the fact that marriage equality was a necessary battle and it was really important that we won it. We should not allow ourselves to be trapped by believing that a false choice is to be made. A vibrant literature depends on multiplying the number and kinds of voices that are heard.

The Destroyers is out June 27 through HarperCollins.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.