"I do this to prove my 13-year-old self wrong."

This is the answer playwright and actor Jordan E. Cooper gives me when I ask him why he creates as his play Ain't No Mo' at New York's Public Theater prepares to close on Sunday, May 5. On his mind lately has been Nigel Shelby, the 15-year-old teen who recently died by suicide after anti-gay bullying.

"To prove to him that my breath is worth breathing, my heartbeat is worth beating," he said, his eyes wet. "To prove to him that he is welcome, even if he has to pull himself a seat at his own table. And that tomorrow is coming..."

The 24-year-old and I are sitting in the Public Theater restaurant just moments before his call time to get into makeup as the lead of his play. He's unassuming on the surface, wearing black pants, a matching crew sweatshirt with icon Whitney Houston's face on it, and a black fedora. But the New York Times describes him as someone part of "a generation of Black playwrights whose fiercely political and formally inventive works are challenging audiences, critics, and the culture at large to think about race, and racism, in new ways." And the more we talk, the more I can see it, too.

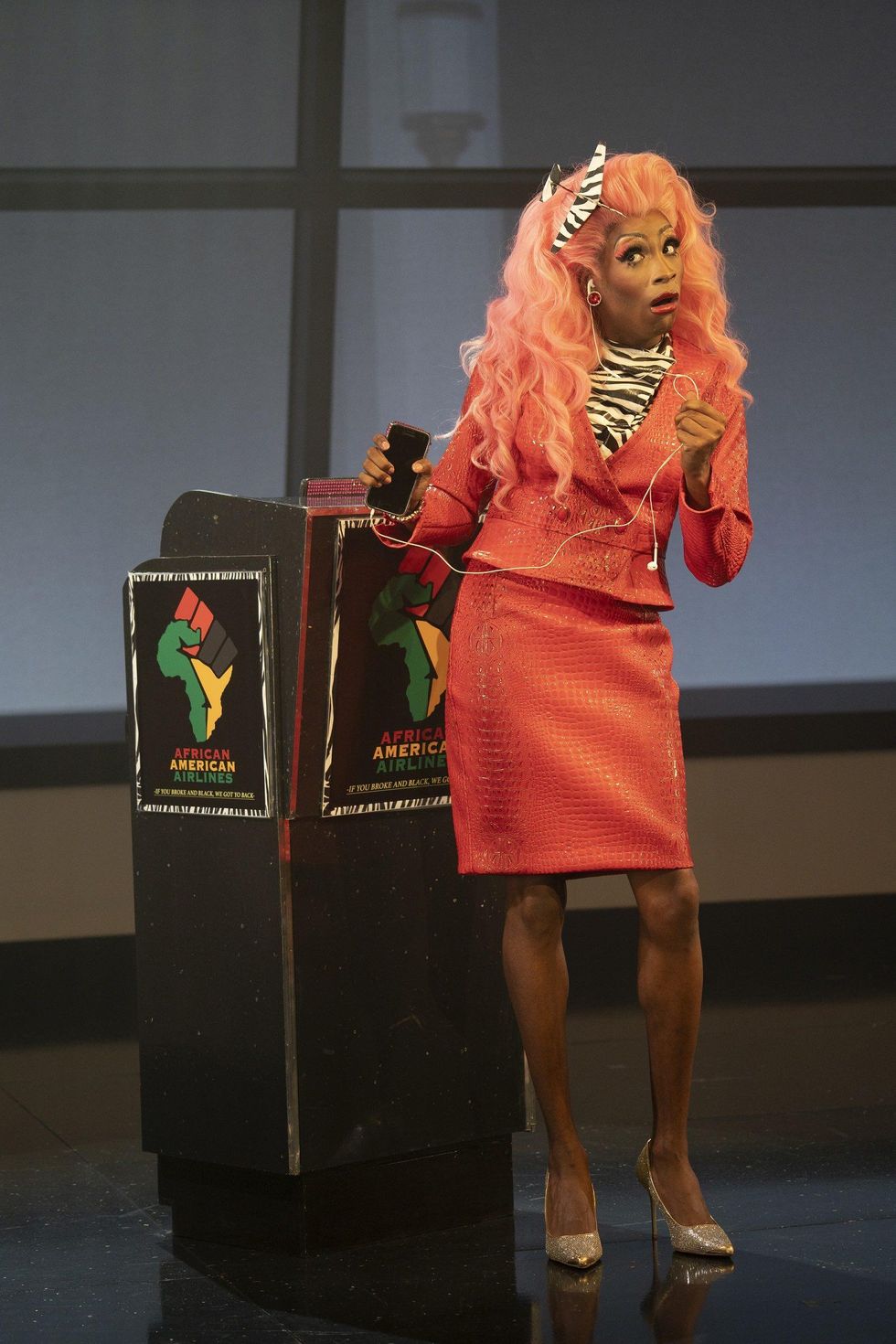

And I can see how his mind conceptualized Ain't No Mo', which I can only describe as audacious. About the last day in America as Black people stage a mass exodus, a la Marcus Garvey, from a country that could elect someone like Donald Trump after someone like Barack Obama was president, it's an examination of the value of Black lives and Black culture with a drag queen named Peaches at its center. The play is at once unapologetically Black and queer af, challenging audiences to take a look at themselves through an immersive experience they've surely never experienced in New York theater heretofore.

Cooper plays Peaches and is supported by a stellar cast that includes Jennean Farmer, Fedna Jacquet, Crystal Lucas-Perry, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Simone Recasner, and Marchant Davis. (The performance I saw two days before this interview featured understudy Hermon Whaley Jr. -- who I ironically went to high school with -- in the lead role and he did not disappoint!) It's directed by Stevie Walker-Webb.

Below is my conversation with Cooper, a Hurst, Texas, native. We discuss the play, his meteoric rise to acclaim since graduating from New York's The New School not even a year ago, and how he deals with creating Black, queer art for audiences not Black and queer. We also talk about what it means to have someone like prolific director-producer Lee Daniels in his corner.

I was watching your interview with Lee Daniels on the The Breakfast Club and he said Ain't No Mo' "fucked up his soul." I couldn't have said it better myself. Where did you get the idea from to have all Black people go back to Africa?

That started out of my own inner workings and depression. I started [writing] in the summer in 2016 when Philando Castile and Alton Sterling [were killed], and then the Dallas [shooting] happened. Then I also remember -- I haven't told many people this because I just remembered it, but -- I remember being at 7-11 and getting a cherry Slurpee. There was a cop next to me and we were both getting Slurpee. And when I went to grab the knob, he reached for his gun. And I remember being like, "Yo, you see me getting a Slurpee!" And I remember that night I just had to process a lot and think about what would've happened if he had done what he wanted to do. But also sit in the pain of losing my brothers and sisters who have gone before me. I'm the kind of person who likes to laugh at stuff... It's like I wanted to take all this pain and turn it into laughter, so that's what I tried to do with it.

Your main character is Peaches, a drag queen. She's the only queer character in the play, but central to the narrative. Why?

I feel like being Black and queer, you're at the bottom of the totem pole. There's something about having this queer person in charge of Blackness and to get all these Black people onboard that will ultimately be forgotten in the end. What does that mean?

Walking into the show, the Negro National Anthem that is "Back That Ass Up," among other hip hop songs, is playing. Attendees are also invited to approach this bag and drop in something that Black people gave this culture. So, it's Black af from the start, but there were only like 30 Black people in my audience of well over 100 and the broader theater-going audience isn't Black. Did you consider that as you were putting it together?

Not at all. I tried to not think about white people period when writing this play because I was so focused on us... I always tell people I don't necessarily write for other people in the sense of traditional, "I want to tell somebody a message or tell somebody a story." Most of the time, it's because I need to hear a message. It's because I need to be healed from something or I need to ask myself question. I don't look at myself as Jesus with two fish and five loaves of bread. I'm trying to eat, too. If y'all can get you some, come get you some. And every night, we kind of make the table a little bit bigger with each audience. I wanted to write for my people.

Is it a different experience for you as the actor doing it with a Black audience versus --

Absolutely. Because Black people will talk back to you. They will have a good time. They will say what they want to say, do what they want to do. And Peaches gets to have more fun whenever there are more Black people around.

There's been a lot of attention foisted upon you and this generation of young Black, many of them queer, playwrights. What do you think that attention says about the work that y'all are doing, or about the broader industry as a whole?

For us, it's more than a moment. For us, we're finally being heard. I had a white person say to me, "Black writers are actually writing plays that are really profound now and getting produced now." I'm like, We've always been writing profound plays. It's just that y'all want to listen now because y'all got a jackass president who doesn't want to listen to you. I think whenever white people feel victimized, they're more likely to hear the victim.

Considering how immersive the play is for the audience, what have you seen in terms of their responses? Have there been walkouts?

I don't know about the other actors, but for me, I have to process it, because for Peaches, the audience is her second performer. The script is never the same every night, because it really depends on the audience and what they're giving me and how much fun we're having and how far I can go with it.

It's been so interesting watching, because we've had a lot of walkouts, but the walkouts are mainly white people, mainly older white people who thought they were coming to see a Public Theater play that allowed them to be a spectator or are used to Black plays written for white people, so it's easier to digest and easier to understand and they have a way in. And that's just not this play.

Stevie, my director, always likes to call my work chitlins on fine China. He's like, "You write for Black folks. You write for blue collar Black folks and you just happen to be in these institutions that aren't used to those audiences... I feel like in the last couple of weeks, because of The Breakfast Club and different media, we've been able to get the right audiences in that I want to see... Because this is new for them, too. They're not used to this type of work. I think we're all learning how to make sure we're getting the right people to see their name on the door. The problem isn't money, because we will pay money for some Jordans. We will pay money for a Beyonce concert or to see a Tyler Perry play and sell out a stadium. It's just about, are we seeing what we want to see? Is what we're seeing related to us in any way? Are we going to feel welcome?

So you're bringing something quintessentially Black into a white space, but also doing something quintessentially queer, even in front of sometimes Black and non-queer audiences. Did you question yourself in doing that?

I never question myself in the work as much as I question how this work is getting to the right people. I never think about whenever I'm writing a queer story or whenever I'm writing a Black story because I'm Black and queer and they're always going to coexist. They're always going to be melting in the same gumbo pot. I just let the work be and whoever wants a part of it or sees themselves in it can see themselves, because I don't necessarily always right queer characters. Peaches was my first queer character that I ever wrote... but she was a bridge or a gate open to actually challenge myself in a lot of ways when it comes to my career. My next play is questioning what it means to be Black and queer and a Christian. What does that look like? Who is God? What is God? And what does queerness look like inside of a Black body?

I want my work, just as I hope the world is to be, [to be a place where] Blackness and queerness coexist unapologetically and realizes how much akin they are. Because a lot of people want to equate queerness to whiteness when in reality, queerness was here before whiteness.

When I was at Morehouse, I started saying to my group of friends that "the Blackest thing you can be is queer and the queerest thing you can be is Black."

Yes. I love that.

As you're going forward and figuring out what your next projects are to come, do you feel any pressure to keep being the hot new thing?

To be completely honest, I let a lot of it go in one ear and out the other. I appreciate it, but when it's in there, it's in there for a second... I feel like it's the same reason why I don't read those reviews because I feel like if I'm going to frame this [positive] critique, whenever it's not what I want to hear, I also have to frame that critique... If I take too much pride in it, then I start to think too much and it starts to become like a formula and trying to do the same thing. But in reality, none of those things matter. For me, I'm a Christian, so it's like I can't take any of those things into the presence of God and be like, "Look, my work is done because Ray-Ray said this was the shit."

But what I can take is that person that I actually helped, that thing that actually shifted in myself as well as another person, that thing that shifted somebody from committing suicide. That's the work. That is the hot new thing. Every time I sit down to write, that's the goal, never the praise. That's the reward.

But it doesn't hurt to have the good reviews and someone like Lee Daniels in your corner as a producer. How do you think things would be different if you didn't have all of that?

I mean, I didn't always have it. Because I've been writing plays since I was 6 years old, and I remember my first plays when I was a teenager. One of my first plays, which was horrible was basically Rent and Fences had a baby, and I called it The Catch. And there was a reviewer who said, "Maybe Mr. Cooper should consider graduating high school before he writes again." That crushed me. And I think that's when I learned not to take -- it's really cool, don't get me wrong. It's dope. I'm grateful for it. But I know that I can't put my worth in it. And I can't put my work's worth in it, because the work is me. I can appreciate it and I can celebrate it, but it can't be the end-all be-all. Because one day it might not be here. And if all my worth is put into that thing that can come and go, who am I and what is the work? ... You just do the work and pray somebody sees it.

Is there something about this play in particular that you want to make sure for these last few shows that people aren't ignoring or letting go over their head?

I think for Black folks, we come in knowing that this is a national emergency. That we're living in a national emergency. And we have been for 400 years. For them, they've been living in it for four years. I want them to walk out prepared to fight, prepared to fight for what's theirs, to not give up, to not give over their ancestors' blood and their ancestors' bones to the likes of savages. And to know that they are worthy and they are the most beautiful creatures that God has ever created. Blackness is. And that is worth being celebrated in all ways, and that we have to be ready.

This play is so special to me... The first day I moved to New York, the first theater I came in contact with was this theater. I remember I wanted to see Hamilton and I couldn't afford a ticket and it almost felt like I wasn't welcome, like it was some secret thing. I just want people to know that they're welcome. I want the work to welcome people, and not only people in the audiences, but actors. Like Peaches, it's not every day you get a role where, for instance, an effeminate Black man can walk into an audition room and be himself. Or that Black women can show their versatility in so many different ways in one play and play different characters in one play and not have to go in always playing the ratchet or the maid. I write for Black people. I love Black people! There's not enough space in the world for their magic, and we just got to stretch the world a bit.

For tickets to Ain't No Mo', click here.

RELATED | Eight Queer Highlights of the 2019 Tony Nominations