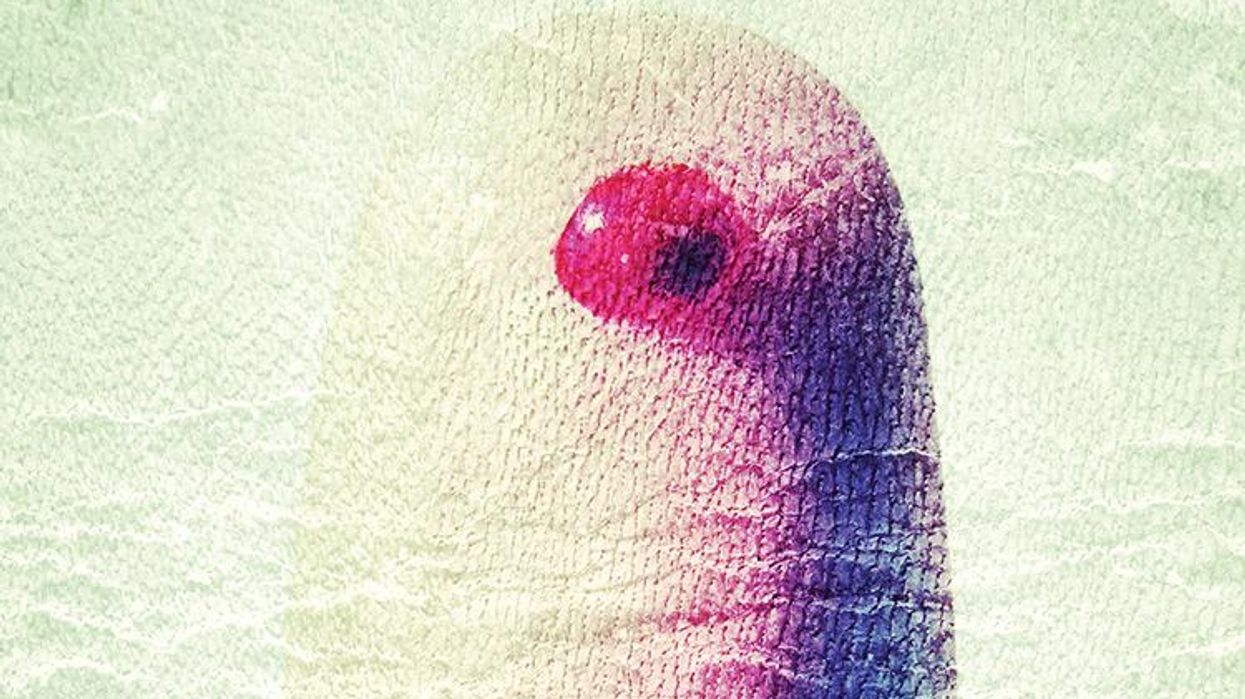

Illustration by Keith Negley

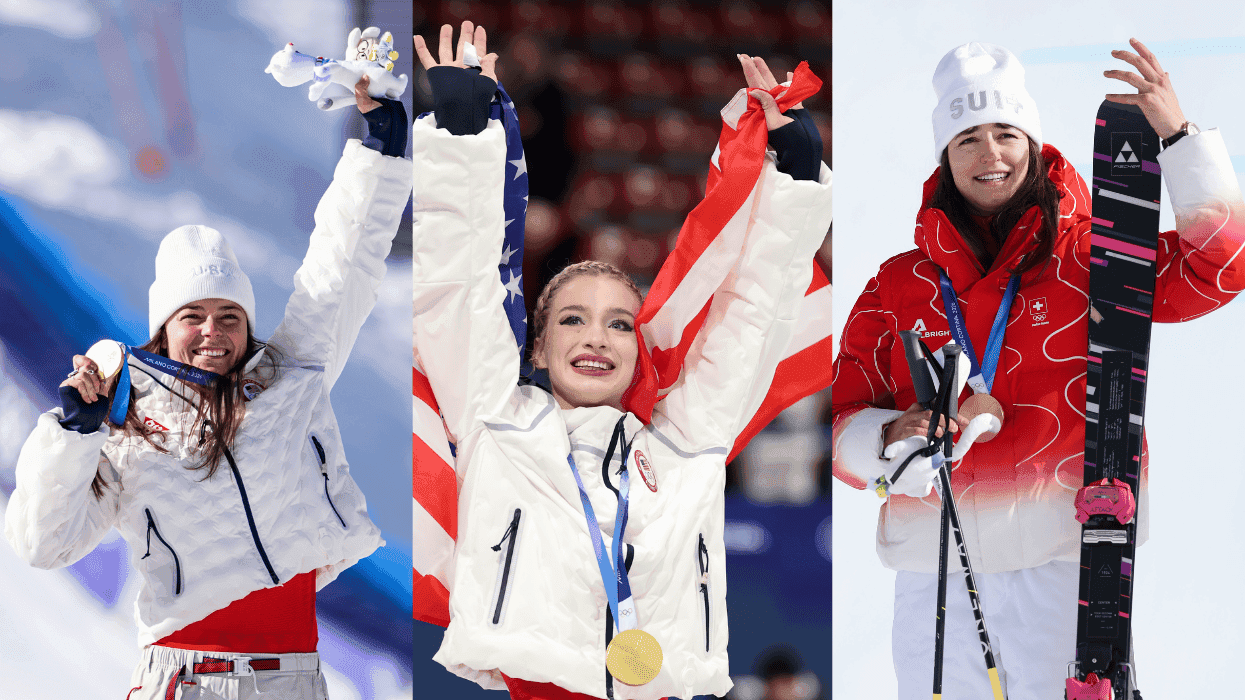

In the second episode of the new season of HBO's Looking, Patrick lets a possible bedbug bite become something that quickly eats away at him. He notices a rash on the side of his torso, and almost immediately asks his buddy Dom, "It's definitely not AIDS, right?" Dom gives him a friendly brush-off, leaving Patrick to his self-examination, and within a few scenes, Patrick is staring at a computer screen full of Googled rash images while talking to an HIV helpline attendant on speakerphone. He gets her name ("Noelle"). They gab about Murder, She Wrote. He asks her questions she couldn't possibly answer on a call. For me, the scene was funny, until it kinda wasn't.

More than ever, I saw Patrick as a funhouse mirror -- a warped, exaggerated reflection of me, with familiar neuroses and self-imposed hurdles amped up for good TV. I never asked the attendant's name, but I've been on that HIV helpline call, and I've scrolled through more symptom image searches than I could possibly count, wondering if the hives on my palm were signs of my T-cells plummeting.

When I was 21, out of the closet and dating men for less than a year, I went home with a guy from the Air Force who was visiting town on leave. The night was fun, exploratory, and very low-risk, but eventually there was enough skin-on-skin contact to cause me to pump the brakes, before jumping into a Patrick-esque horror house of delusions. Like many, I was a gay man hardwired with a fear of HIV, which comes entwined with the guilt of embracing a life you're warned against. First came the muscle aches, and then the dry throat, and by the time something visible like hives manifested, I'd already wholly convinced myself I was infected.

It's embarrassing to admit the full scope of this fear. I was commuting to college, living at home with my parents, and my HIV terror permeated every layer of my life. At school, in my creative writing class, the only story I could manage to write was about a young man dying of cancer, who self-medicates with quarts of liquor. At home, where my being gay was still very much taboo, I spilled mortifying details about my encounter, hoping my parents would sympathize and help me get answers, or maybe treatment. (My father, clinging to the notion of a wife in my future, almost had me sold when he told me, "Maybe all this will teach you a lesson.")

My family doctor told me I was wildly overreacting, and introduced me to something I still remind myself to respect: the immense power of psychosomatic phenomena. The fact that stress could be producing actual aches, spasms, nerve pains, and visible spots seemed preposterous, and on top of that, the most definitive help my doctor could offer was a test with a six-month window, after which I could officially declare myself HIV-negative. I persuaded my parents to take me to a specialist, who provided a faster, fancier test, which, supposedly, could detect antibodies and give patients firm answers in three months instead of six. The specialist told me to relax, as did the sweet Air Force guy, whom I called incessantly until he stopped picking up.

Three months passed, I was tested by the specialist (for the second time), and the results came back negative. It was an uptick, but it wasn't the end of the road. After all, my other doctor said it would take six months to be fully certain, so I could only walk around breathing half-sighs of relief. Anything more would be irresponsible. Three more months passed and I was clear. Negative. Free to define myself by something other than looming illness, with the clarity to finally acknowledge, as Dom does in the same Looking episode, that "irrational AIDS panic" can be offensive to those diagnosed and the people who love them.

Hypochondria can operate like a drug -- a crippling, self-deluding distraction that people, particularly young people, can employ when avoiding their current circumstances. Patrick wasn't ready to confront the realities of his relationship with Kevin, his partnered boss who didn't seem to be leaving the beau anytime soon. I wasn't ready for all that came with being a young gay man, or even a man uncertain of what comes after college. Instead of facing my fears of the future, I found a new fear to which I could obsessively devote my energy. I unwittingly wanted an escape from my life, so much so that I drove myself mad by agonizing over the end of it.

Search

Latest Stories

Sign me up!

See what's new and hot in queer entertainment, in your inbox three times a week.

@2026 PUBLISHING INC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

The Latest

More For You

Most Popular

Load More

@2026 PUBLISHING INC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

I watched the Kid Rock Turning Point USA halftime show so you don't have to

Opinion: "I have no problem with lip syncing, but you'd think the side that hates drag queens so much would have a little more shame about it," writes Ryan Adamczeski.