How do you start a revolution? Sometimes, the best way is to look around, realize there's been one going on, and add your voice and your vigor to the cause. That's what Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi did when they founded Black Lives Matter in 2013.

Related | Asia Kate Dillon, the Gender-Nonbinary Actor & OITNB Star Making TV History

It's what Asia Kate Dillon, the gender-nonbinary star of Billions, has been doing on social media and in their groundbreaking role as Taylor Mason on Showtime's high-octane drama about the rich and powerful. As a gender-nonbinary trader in a room of alpha males, Dillon has challenged lazy assumptions around gender in the least likely corners of America. And they've also been a vocal and fervent support of BLM -- in January they wore a #BlackLivesMatter hoodie to the 2018 Critics Choice Awards. Dillon recently sat down with Garza to discuss how we talk about identity, community, and the cages -- gilded or otherwise -- that hold us all prisoner.

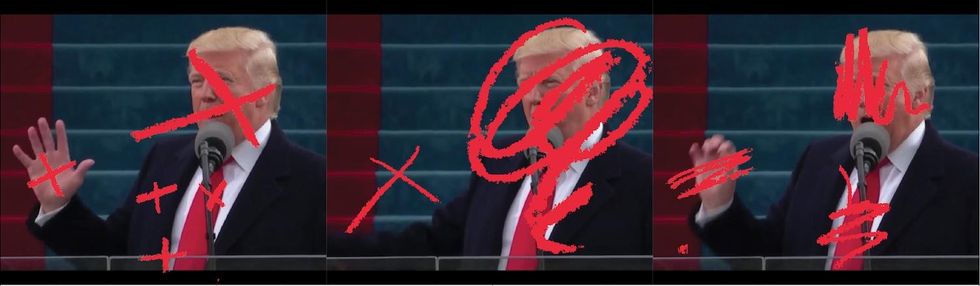

Aaron Hicklin: One narrative that quickly emerged in the aftermath of Donald Trump's win in 2016 was that it was in some ways good for America because it would force us to confront the bigotry and violence at the heart of our society.

Alicia Garza: I have heard that sentiment a lot -- not necessarily that Donald Trump is good for America, but that it is important for this country to experience something like this so that change can happen. But the danger of a narrative that this is good for America is that it assumes that there will be some good outcome from it. I'm certainly an optimist, but not that optimistic. I wouldn't even assume that this has been such an awakening for the country, that it will automatically cause a shift, either in 2018, for the midterm elections, or in 2020. I think some make what happened with the election of Donald Trump much more simplistic than is useful. This was not a fluke, but in fact the result of 30 years of really smart and sharp organizing by conservatives. And this moment, in 2016, was a demonstration of how much power they have built. Given that, I think we should all be mindful that nothing is going to shift without some really intentional organizing, and without a long-range vision of what we're trying to achieve. In the short term, we certainly want to rid ourselves of Trump, but it seems that we also want to rid ourselves of the ideology and the world view and the politics that got Trump elected in the first place. What do you think about that, Asia?

Asia Kate Dillon: The question "Is 45 good for America?" Well, whose America are we talking about? And is 45 good for America because he's showing us who we are? Well, who is the us? The America that 45 is "good for" is liberal, white, straight, cis America, to begin with, and the awakening of the white liberal always comes at the expense of historically marginalized and disenfranchised people, particularly those of color. When those of us who have been part of any historically marginalized, disenfranchised group woke up on November 9, it was not very different than any other day, as we know it in our own lives or in the history of America. If anything, it just forced us to reckon with of our commitment to the fights we've always been fighting. I think it's really important to acknowledge -- I'll just reiterate your point -- that the election of 45 is a result of a carefully thought-out and implemented plan by racist people in all different kinds of positions of power. And, as you said, in the short and intermediate term, really well-thought-out organization is going to be key. And it really begins with holding a conversation around the fact that 45's election was a result and a demonstration of power that has existed since the first enslaved person was brought here over 400 years ago.

Related | Out100: Alicia Garza

AG: Absolutely. The thing I've really been grappling with for a few years now is do I want to save America, given its incredibly violent, racist, homophobic, and sexist history? And I guess what I'm coming to right now, without getting into a lot of details around the validity of nation states, is that what I want to fight for is a different kind of "we," and a different way that "we" can be. So, one of the questions I get asked a lot is, "Where do white people fit into that, and especially white cisgender straight folk?" And, two, "Is it possible to have a 'we' that includes all of us?" And where I'm landing is that I have to believe it's possible, or else it's hard for me to see a future. I don't see a future where any of us can sit out or get left behind, and then think that we're going to achieve some kind of victory. We talk about that a lot when we talk about how none of us are free until all of us are free. I've really been grappling with the question of where white folks fit in. And how much of our energy do we spend trying to "convert" people who are following this maniac? And what about those people who aren't following this maniac, but they're certainly still a part of the problem? And where I'm landing is: I think this version of America is good for no one, including white, cisgender straight people. Because if we're able to zoom out a little bit, we can talk about the ways in which America as a country functions as a predator -- meaning that the engine of America preys on everyone, and it is only selective in the type of bloodsucking that it does. And I'm curious: How do we get to that "we" that helps us understand that we're all connected? What do you think it would take to get there?

AKD: I think I'll start with where do white people fit. That's a question I think about a lot as a light-skinned person who has benefited from the invention of whiteness. I have taken what I feel to be instructions from people like James Baldwin, and certainly most recently Ta-Nehisi Coates, and from the Black Lives Matter movement, and come to an understanding that it is my job to educate other white people about racism and oppression, and that the burden of explanation should not be on the oppressed. I just picked up The Fire Next Time, and Baldwin is able to state that he identifies as a black man while also understanding that it's all a construct, which gets to what the "we" is, and how do we make a "we" that is actually all of us. And I think it's coming to the understanding that people with light skin who benefit from the invention of whiteness were given privilege and power that we never earned. And that realization can be scary, but ultimately it means that white people are in a cage too. It's a gilded cage, but it's still a cage, and that cage separates us not only from our fellow human beings, but our own humanity. That understanding, to me, seems like a place to start in terms of how we create space for all of us and a new definition of "we." And that "we" has to include the 45-ers. The same racist laws that created mandatory minimum sentencing that put predominantly young men of color in jail, at disproportionately high rates, also put white people in jail under mandatory minimum sentencing. And the people in the Midwest who are like, "What about my white son who is in jail for a small possession of some drug, and it's ruined his life -- why is it that way?" Well, it's actually because of racist laws that exist, and if you work towards dismantling racist laws it will affect every single person who is in the criminal justice system. We need to show people the tangible ways we're all affected by the racist system and racist capitalism in which we live.

AG: Your awareness of things like mandatory minimums made me think about the investment that white supremacy has in hiding the stories of how white people are being impacted by mass incarceration. It made me think about a white family I know. Their son was incarcerated, experienced incredible torture inside of prison for a petty theft, was eventually released from jail, and developed such incredible paralyzing responses to the trauma experienced inside that they committed another crime, because all they knew was that. And then they killed themselves in jail. Those are not the stories we hear.

With the Parkland students, who've been incredible heroes, I've been asked many times: "Do you feel the faces being lifted up are white faces, and that's why they get to be heroes?" Instead, I would say that I hope these young students -- not all of whom are white by the way -- would use this time as an opportunity to point out, "You're not going to divide us -- we're in solidarity and alignment with Black Lives Matter, and with all these other movements that are trying to move the needle around some of the big problems we face." If we are able to do that, what would we be able to accomplish?

AKD: The Parkland students are incredible, and one thing that has really buoyed me and given me hope is the fact that they are creating what feels like an intersectional, inclusive conversation. But I'm also struck by news coverage and the way it has presented the students as "the face of the movement we've been waiting for." My immediate reaction was like, OK, but what about the people who marched in Florida when Trayvon Martin was killed? And what about all the people that marched in Ferguson, and what about the fact that Ferguson was declared a state of emergency, and federal marshals were sent in with machine guns? I'm very aware of the ways in which groups of people of color who gather together in a peaceful manner are treated as terrorists, and the ways in which groups of white people who gather together to do anything from burn the American flag to loot stores to riot after a sports game are treated as, like, heroic young people.

I think it would be helpful to reframe the conversation around the disproportionate violence that people of color experience at the hands of the state -- when white police officers who have shot a black person eight times, 10 times, 20 times, say, "Well I was afraid for my life." I've observed that we -- the general we -- tend to respond by saying, "Well that's impossible. There's no way that police officer could have been afraid for their life. It was clear that black man was running away from the officer with his hands in the air, saying, 'I'm unarmed, don't shoot.'" And I feel like if I challenged myself to actually hear that statement -- I was afraid for my life" -- and then say, "OK, in what ways could that actually be true? Because of the society that you were brought up in, which told you to be afraid of black people, and particularly in an environment where you're a cop, and you haven't been taught how to de-escalate the situation?"

We don't talk about the ways police officers really might be afraid for their lives because of the racist society they were brought up in, and that they don't recognize that. So, that's a good reframing of the conversation that might lead to a reframing of the headlines. As we all know, it doesn't matter what a person of color has in their hand, or if their hands are up or down, or on the ground. It doesn't matter. The fact is they are a person of color.

AH: I'm thinking of Lydia Polgreen, the editor in chief of HuffPost, also a queer woman of color, who suggested that one reason journalists didn't anticipate Trump was because they weren't outside the cities, and they weren't writing enough empathetic stories.

AG: Empathy is important -- it's important to understand that we depend on each other to survive. There's just no getting around it. As much as 45 wants to whip up all this fear and hysteria, and increasingly cut us off from each other, we can't live like that. At the same time, empathy doesn't go far enough for me because as a black person who has moved the needle around social change, the burden of empathy is often put on my shoulders. So, I'm supposed to be empathetic to the family of police officers who have been shot at or killed; I'm supposed to be empathetic for the Trump supporter who just didn't know what they were getting into. Empathy is a really easy way to avoid responsibility and to place it on the wrong shoulders.

I think part of what we need to do as storytellers is tell more complex stories -- telling complex stories reflects the way people really live their lives. I feel the reason cops are scared for their lives is because they don't actually live around the communities they police, and that is intentional, and the desired outcome is that we don't understand each other. A couple of white people live on my street in East Oakland, which is mostly people of color, and they're not scared of people of color because they have everyday interactions with people who don't look like them. You see these people at the grocery store, and you might depend on them to help you with a flat tire, or they might stand outside your door if they think you might be in danger. Empathy, for me, is kind of like a gaze that assumes a level of privilege and says, "Let me at least try to connect with someone who's different from me." But it doesn't actually challenge us to uproot the system that supports us being disconnected from each other.

AKD: I really feel like empathy is necessary -- it's a great starting place. And then it becomes the conversation about how we dismantle the systems that separate us from ourselves. How do we tell better, more complex stories, and how do they underline the fact that these systems are absurd, and therefore unnecessary? And in truth, racism is absurd, when you really break it down. I think that creating stories that turn into conversations around that idea is a way to bridge the gap that empathy leaves.

AG: I think that's gangster. So maybe what we need to start saying is, "Where do you stand on the power scale?" For me, my identity is as a black, queer, cisgender woman. I walk through the world every day experiencing how power operates on me, and how I exercise power at the same time. And that understanding is necessary for me to be an active participant in a movement geared toward social change. I want to understand how I irresponsibly wield power and how power is wielded upon me, and what that means for my life's chances and my life outcomes and for those of other people.

AH: Can you both expand on what wielding power responsibly means for you?

AKD: I was recently boarding a Metro-North train and could not find on my tickets what track I was supposed to go to, and with an awareness of the fact that cops inherently make me nervous because of the lens through which I am looking at things, I still walked right up to a cop to ask for information. As I boarded the train, the thought that went through my head was, If I were a person of color, it would be very unlikely that I'd approach that cop. So then I miss my train, so I'm late to work. Maybe it's the first time I've been late to work, or maybe it's the third time. Maybe that means I get fired and I lose my job, and then I miss out on two weeks of paychecks to feed my family, or to feed myself. Not only do I wield that power, but I'm also trying very hard to be conscious of the ways in which people who don't have my power are affected by a situation.

AG: I have been conditioned to see and move through the world in a bunch of different ways. As much as I don't believe that black people have a particular level of pathology that keeps us from being successful, I was raised in many ways to think that it was important to be an exception to the rule -- and that is racialized, and it's also about class. And it takes a lot of work and intention to dismantle it. It's a process I have to go through every single day: to ask myself why I believe what I believe. How do you know?

AKD: You said you live in Oakland in a neighborhood made up predominantly of people of color, but you have a couple of white people who live there, and they're not afraid of people of color. That's one of the powerful things about visibility and representation in the media. So, Lena Waithe on the cover of Vanity Fair -- there are places in America where there are no people of color, and if there are queer people they are definitely not out, because it's not safe, but Vanity Fair is on the newsstand. And Lena Waithe's face is there, and she's an out, proud, successful, queer woman of color. And someone in some town, some kid of color or some queer white person, is going to pick that up and feel less alone. To be frank, it could save a life. That is the power that visibility and representation have, and that's why it's so important in the media -- because the media can reach places where there's only one person of color, one queer kid, and they feel less alone.

AG: What I loved about that cover was that Lena was not in a ball gown. Every time I've seen Lena at awards shows she's wearing suits. Giving me a little taste of dandy. I'm here for it 100 percent. It's a really complicated expression of gender, and I'm loving it.

AKD: It goes back to what you said about understanding that identity exists as a map of power. As a queer trans person, I still have more power than you because of the color of my skin. So, I'm a marginalized person, but I also still hold power. We have to acknowledge that, and then make sure we center the people who exist at the outermost margin.

It is the people who are the most disenfranchised, the most marginalized, who can see the forest for the trees, and who have the blueprints for solutions for the problems that affect us all.