When the 2017 Oscar nominations were announced on January 23, the Academy advertised its newfound interest in championing otherness in Hollywood. A vividly gay romance (Call Me by Your Name) was among the Best Picture contenders; Greta Gerwig (Lady Bird) became the fifth woman in history to land a Best Director nod; and Get Out, Jordan Peele's racism-skewering horror film, surprised many with four nominations, including Best Picture. It was, as writer Mark Harris put it in a November prediction piece for New York magazine, a reflection of "an attempt at the First Woke Oscars."

But there's a much more nuanced conversation to be had about the state of queer cinema, which, last year, had a more noticeable presence outside the Oscars' 24 categories. And queer directors in particular seemed to be putting more stories on screen.

Among them was Dee Rees, a black lesbian who amassed a largely female crew to make Mudbound, Netflix's epic World War II saga about race relations. There was also Robin Campillo, a gay French filmmaker who survived the AIDS crisis, and poured his experience of working with ACT UP Paris into the verite case study BPM (Beats per Minute). Angela Robinson, also a black lesbian, released the biopic Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, which dealt with queer polyamory while tracing the origins of a superhero. Gay director Damon Cardasis sought out trans actors to fill the cast of Saturday Church, his underdog film about a queer youth center. And trans black filmmaker Yance Ford released Strong Island, a deeply layered documentary about the long-dismissed murder of his brother.

Related | BPM, a Definitive AIDS Epic

Some of these directors caught the Academy's eye: With a nod for Best Documentary Feature, Ford is the first trans director ever nominated for an Oscar, while Rees's Mudbound made Rachel Morrison the first female nominee for Best Cinematography. And some of them didn't. But all of them, in their own very unique ways, added to a growing tapestry of queer visibility on screen. They recently sat down with Out to discuss the mechanics of their mission.

OUT: Before this year, when you looked at the queer film landscape, what did you feel was missing, and what did you hope you could bring to it with your work?

Angela Robinson: What I thought was missing has really started to appear -- in the last few years, and especially this year -- and that's a movement beyond the coming-out story. I want to see representation of queer characters, but I'm also excited to tell interesting stories about other stuff in their lives, which may reflect that they're queer or may not. It was also very important in my film to move beyond problematizing gayness. The characters never discuss whether what they're feeling is good or bad. It's always about how they're going to live their lives in a repressive world. There's no "I'm bad" -- there's just, "I feel this way. So now what?"

Damon Cardasis: I was so inspired by kids at programs for at-risk LGBTQ youth. They have so much strength and perseverance, and many of them are trans people of color whose voices are not often heard. Diversity is massively important, including within the queer community, and I wanted to show that. I didn't really go in with any intentions other than finding amazing actors. It was interesting to make the movie and then hear all the feedback from people who could see themselves on screen. And to hear that the actors also felt that their voices were being heard meant a lot.

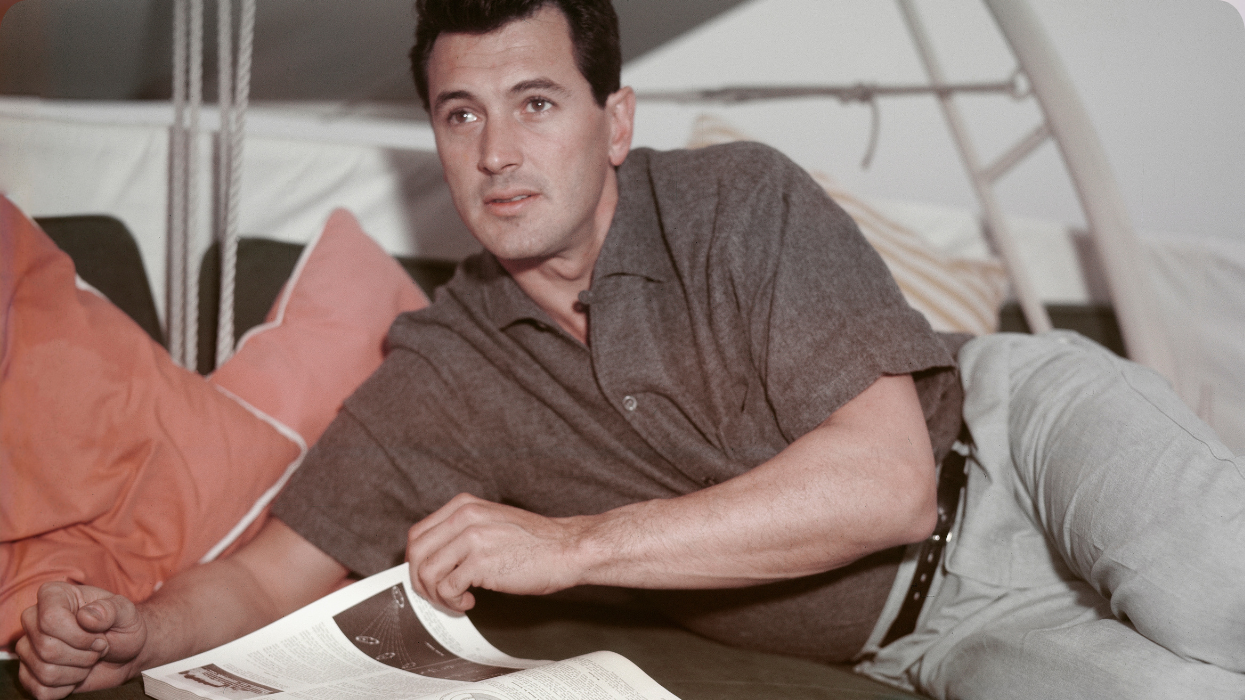

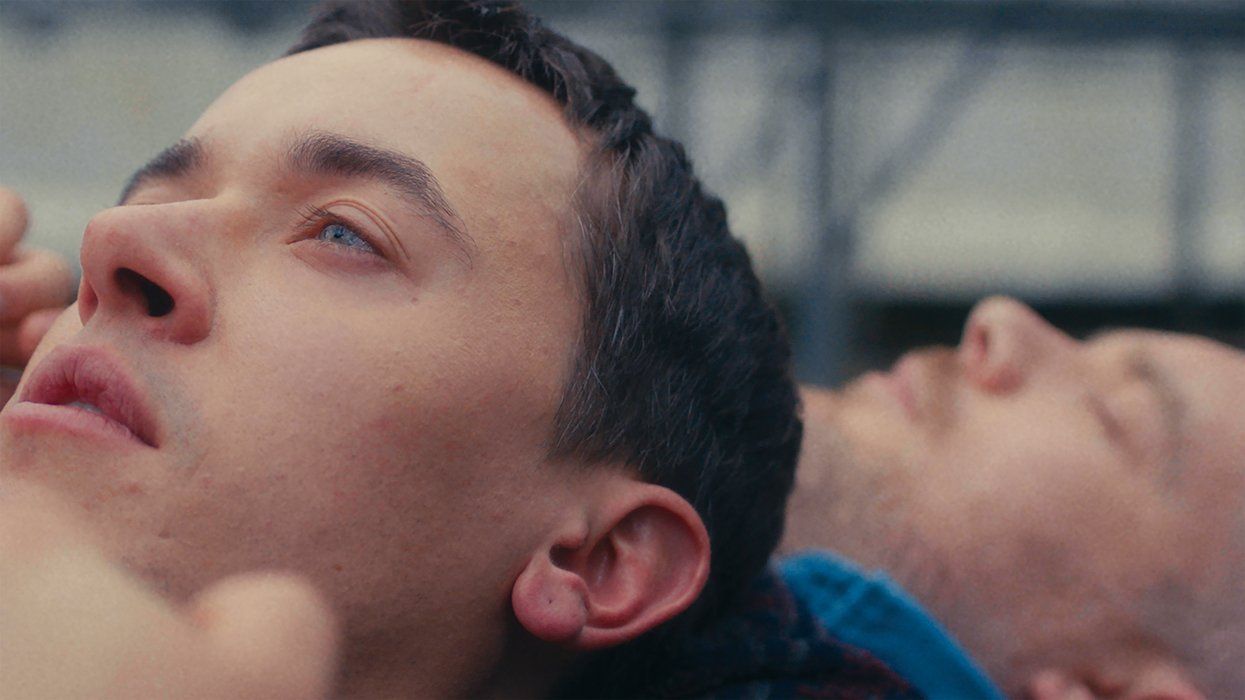

A scene from Yance Ford's 'Strong Island'

Yance Ford: From a queer perspective, it was very important for my film to be true to my experience of growing up and being loved in my family. There's a part in Strong Island when my parents decree to us that, no matter what, we love each other. People throw around unconditional love as a term, but when it's put to the test, it doesn't usually hold water. My family embraced who I was, especially my brother. I found out later from talking to his friends that he was fully aware that his little sister was gay. The black community has a reputation for being hyper-homophobic and hyper-transphobic. My family's unconditional acceptance had to be as seamlessly integrated into the film as it was into our lives. And I can't tell you how many times I've had queer folk around the world say, "Thank you for showing a family of color loving their black queer child, because that is my experience."

Related | Dee Ree's Epic Netflix War Saga Mudbound

Dee Rees: With Mudbound, I just wanted to tell the full story, especially about race. We have to look at things like our shared history, our collective history, and not just your history or my history. Once we figure that out, it's all a connected history. For example, I can trace my lineage back to slaves, and someone else can trace his lineage back to slave owners. These weren't mythological creatures. Once we're honest about the intertwined nature of our history, whoever we are, then it's easy to address it on a person-by-person level. I think people can probably find characters from Mudbound in their families, and I really wanted to look at how each character had different relationships -- and possessed a different brand of racism.

Robin Campillo: In 1982, when AIDS hit France and the rest of the world, I was 20 years old. As a young gay guy, I was so afraid. Ten years later, when I joined ACT UP Paris, my perspective changed, and that helped me to go back to cinema. I've wanted to do a film about these elements of my life for a while, and it was very important for me to recreate a kind of community, rather than try to explain or lecture. And shooting the movie was powerful because I got to work with all these young gay actors who don't have the same perspectives as I do. Some of them didn't know anything about the history of ACT UP, and at the same time, they still have fears about HIV infection. The film was a big success in France, and I think it reopened a debate about this epidemic, as well as queer identity.

Dee Rees

Is there a particular film that has really inspired you, or given you more permission and confidence as an artist to release the movie you set out to make?

YF: I would start with [Marlon Riggs's] Tongues Untied, which I saw in my early 20s. It's the film that helped me stop apologizing for existing and for being proud of who I was, and it continues to give me courage to this day. It changed the way in which I was able to command my right to exist on my own terms. There's also [Isaac Julien's] Looking for Langston. And this year's I Am Not Your Negro, frankly. I'm one of those people who would have appreciated seeing more of James Baldwin's personal life, which he meshed into his political work, but the director [Raoul Peck] clearly made a masterpiece. There's [Sean Baker's] Tangerine. And Pariah, speaking of Dee's work. There's a spectrum of films, from Tongues Untied through Moonlight, that have reinforced my decisions about how I portray myself and my queerness in my work.

DC: I mean, [Jennie Livingston's] Paris Is Burning, obviously. It's a classic. I remember when I was in school and first heard of the ball community and that whole world. That was all very inspirational. We were in post on Saturday Church by the time Moonlight came out, but I really loved the quietness of that film. It wasn't in your face. It invited you in. That was something I kept in the back of my head a little bit when it came to mixing my film and doing the sound design. I also really like [Lars von Trier's] Dancer in the Dark. Again, I was mostly inspired by the kids and the youth program, and wasn't necessarily looking outward beyond that -- but I was thinking, How do I make this work and turn it into a musical? I remembered how, in Dancer in the Dark, they escape into the musical elements, which are incorporated in a nontraditional way.

RC: I was inspired by a film I co-wrote, [2008's] The Class. It was very technical -- the first film that [director] Laurent Cantet shot with a digital camera. And it's a film about clubs -- about students talking with their teacher and the electricity between people. We tried to find a new way to shoot this kind of thing with three cameras -- not through improvisation, but through capturing reality in very long takes. That's similar to how I structured the debate scenes in BPM. Seven years ago, I realized I wanted to do a film about the HIV epidemic in which the first character would be the words -- the speaking process. Because of The Class, I was able to show how people try to define themselves, and how people changed the perspective about this epidemic by talking about it.

Related | Angela Robinson: Professor Marston Was 'Full-Throatedly Advocating for Feminism'

Angela Robinson

Speaking out has recently become the biggest theme in Hollywood, from #OscarsSoWhite to #TimesUp. How do you respond to that as both a marginalized person and a person in the industry?

AR: I've been very involved in #TimesUp, which I feel is so necessary and exciting. I was really blown away and moved to see it all come together at the Golden Globes -- there was so much commitment from so many women to speak out in such a unified way. My joke is that I've been on a lot of panels because I'm a three-fer -- a queer black woman -- but I definitely feel that Hollywood has a deeply entrenched, systemic problem. That's why #TimesUp is taking a really awful moment and making it into a movement. And it started as a very specific response to sexual harassment, but the next thought is that, in storytelling, gender and racial inequity are issues for the entire planet. It's super important to me that the conversation continues so things don't just go back to business as usual.

DC: A minority fighting for its rights elevates all minority groups. Everyone should be linking hands and joining together because everyone is dealing with this. I think it's also important that people put their money where their mouths are. I feel like every awards season we talk about diversity and how important it is, but then you actually try to find financing and funding for movies about a diverse group of people and it's almost impossible. The feedback is usually, "It's a small film -- it's too small." While everyone is patting themselves on the back, they also need to be really leading by example. Don't just champion films that manage to get through -- actively work to create more diverse material so there's an amazing array of different people represented out there. It's vital to be supportive of what's happening with women in Hollywood, but I also think that support can extend to gender identity, sexual orientation, and anyone else who's marginalized.

YF: I completely echo that. Certainly, fighting for equal pay and representation, and creating safe workspaces for women on sets, behind cameras, and in agencies is important, but what concerns me is that without careful consideration, the things that will be #MeToo or #TimesUp will be restricted to straight, cisgender women -- to the categories that are traditionally thought of as under siege. I hate to say it, but there are often blind spots when it comes to the queer community, and I think the people who are signing up for #TimesUp have the power to make change with that as well. They don't have to wait for other people to make it. I worry that because the queer community is often so marginalized, one segment of our population will be prioritized over an entire group that's influenced creative art, from dance to fashion to everything across the board. I don't know if there are folks who are thinking this movement should include protections and greater representation for those communities, too. I would wave a red flag to avoid a bigger problem down the line, and I believe now is the time to, as Damon said, link hands and join arms. Make it an inclusive movement for change so that, five or 10 years from now, we're not finding ourselves in another hashtag moment about a group of people who were left behind in 2017.

Related | The Irresistible Spirit of Saturday Church

What do you hope to see happen or continue to change in cinema, and how do you want to be personally involved in that?

DR: I hope that art, in a way, may be the long game in terms of changing our ideas. And I think that with art, we're just allowing more and more people to be more honest. For example, before Mudbound premiered at Sundance, we were all at the inauguration day protest -- we had our signs, and were marching and screaming. Then we premiered the movie, and after the screening this woman came up to me crying, and she was white, and she was with a group of friends who were all white. If I'd seen them before in a different context, I probably would have pegged them as Trump voters and just dismissed them. But instead we were crying and hugging because we connected over this film. She could see me and I could see her -- we could see each other as human beings. I'm always a bit skeptical of progress, because it's all cyclical, but I hope and expect that we'll see more of that. Personally, I'm working on a lesbian horror film with [producer] Jason Blum, whose company, Blumhouse Productions, was behind Get Out. In a similar vein to that film, this project is about the exploration of community, and about what it means to belong.

Damon Cardasis and the cast of 'Saturday Church'

RC: I made this film about my past, and that was a big deal for me because it was an obsession for many years. I'm very happy that I closed that door. Now I want to make films that are...something else. I want to show representations of LGBTQIA people, and of our lives, but I really think that cinema is a place of metamorphosis. It's a place to create new images of ourselves -- new perspectives of who we are. We can imagine things that are not part of reality but that could become our new reality. That's what I want to do. I want queer cinema that can reinvent our identities and our future.

Related | Strong Island's Trans Black Filmmaker Yance Ford Calls For Justice

AR: I want a wider range of voices across the spectrum, and I want a wider range of queer voices to receive the support and reach that others do. I'd also like to see more of those voices in mainstream pop culture. I think that happens a lot in television, but less so in films. I want to see representation beyond the space that's already been created for queer filmmakers. And I feel that the #TimesUp movement is truly an intersectional movement that can try to change what stories get to be told, and make room for other stories to be heard. I just want to keep making work. And I want to help make sure that the movement continues across histories and across spaces. I am concerned that we're trying to make this change in Hollywood in particular, but as someone told me, "That may not even be the game anymore."

YF: In the next couple of years, one of the things I really want to do is be a part of subversive queer storytelling. By which I mean, as in Strong Island, queer content emerges in places where you wouldn't necessarily or typically expect to find it. In my life experience, those places are exactly where queer content, queer relationships, and queer issues come from. My hope is that I will continue to tell stories that put queer people where I see them: everywhere.

Robin Campillo

Credits:

Courtesy of The Orchard (BPM)

Courtesy of Netflix (Strong Island)

Courtesy of Netflix (Dee Rees)

Photography by Claire Folger, Courtesy of AnnaPurna Pictures (Angela Robinson)

Courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films (Saturday Church)

Photography by Celine Nieszawer (Robin Campillo)