Sometimes the only way to right a historical wrong--like, say, the constant need of biographers to erase same-sex relationships where they so obviously, and often even shamelessly, existed in plain sight--is to write a novel that tells the truth so persuasively that it overwrites any bias or doubt.

To author Amy Bloom, or anyone with a queer eye, the lifelong love affair between Eleanor Roosevelt and pioneering journalist Lorena Hickok is a matter of fact, documented in decades of blunt correspondence between the two women--a staggering 18 boxes of which are preserved in FDR's own presidential library--not to mention in media reports from the time, when Hickok had her own room just down the hall at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

In White Houses, Bloom builds a rich, intimate and complex portrait of the messy, relatively open marriage between the Roosevelts, especially Eleanor, a famous force of nature who was revered, reviled and finally memorialized as the "world's most admired woman." But it's really a book about "Hick," as Lorena was known, a brash, resilient bulldyke of a news reporter whose groundbreaking career and swash-buckling self-confidence are both boosted and at times overshadowed by her loyalty to Eleanor.

"At its heart, this is a novel," Bloom says. "This is not a newspaper article with a few flourishes. This is how I have come to imagine these characters. I have researched them a great deal, but they are my versions. And my interest lies more in truth than in facts--although if you like that kind of thing, there are a lot of facts in there."

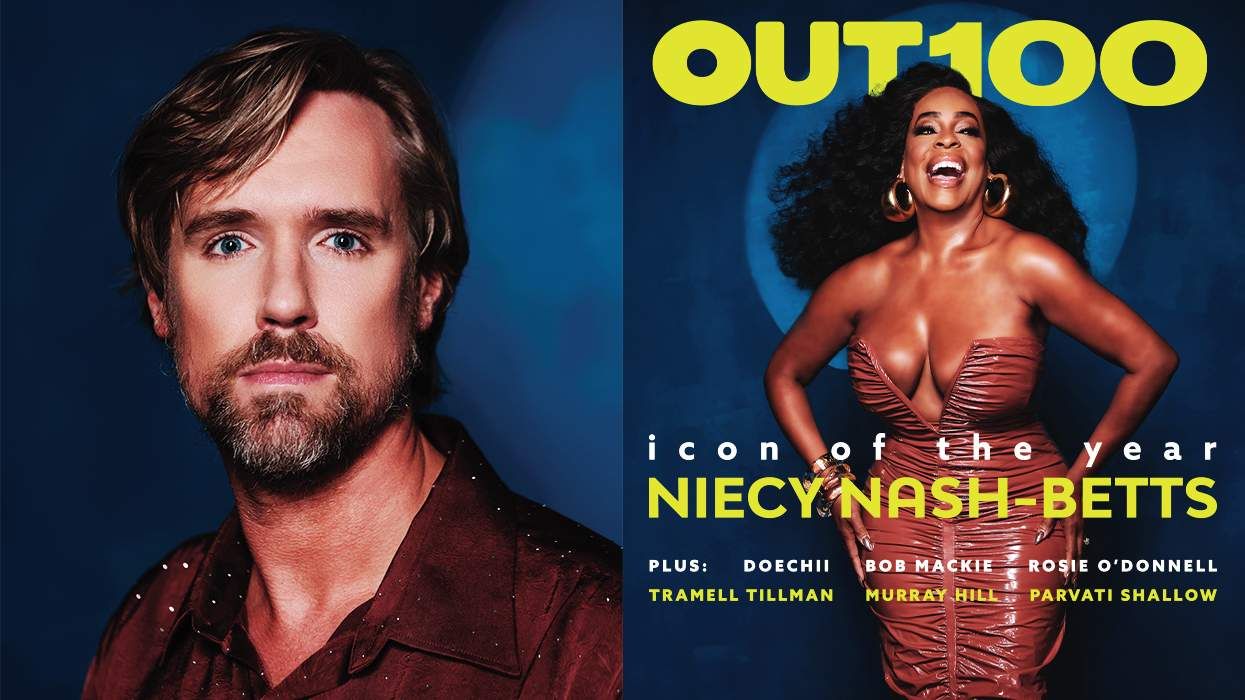

As she celebrates the news that White Houses will be developed for television with Katie Couric setto produce and Emmy winner Jane Anderson set to direct, we caught up with the nominee for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award to talk about homophobic academics, superior first ladies and White House sex scandals.

Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt on July 13, 1960. (AP Photo)

OUT: How did you find your way to Lorena Hickok and this story?

Amy Bloom: Lucky Us, my previous novel, is set in the 1940s, and the Roosevelts cropped up quite a bit when I was researching. And I was very moved by the first two volumes of Blanche Wiesen Cook's biography of Eleanor Roosevelt, in which she refers to these letters, and certainly talks about Lorena. I went to the Roosevelt Presidential Library, and there's something about just looking at the 18 boxes [of letters] and thinking, That's a lot of correspondence for just pals. There was something about this love story that had been lost to history--and lost is really a polite word because it seems to me torn out would be more accurate and more literal. The two of them had been lost and found, and lost and found again in their relationship. And I think both of those things really grabbed me.

Even just a cursory online search about Lorena and Eleanor, what you find it biographers immediately questioning whether they could have been romantic, like, "We just don't know, there's no way we could possibly know that these women were lovers."

Yes. There's no way we could know. And also the idea that Eleanor was a Victorian lady--and I'm like, not really. She went to an English boarding school, for one thing, that [lesbian writer] Natalie Barney and her sisters went to. And all of those fancy French lesbians ended up writing novels about their adored headmistress Mademoiselle Suzette, who took Eleanor on a two-person tour of Europe. And so then the idea that on top of everything else, she's just really effusive, and that she wouldn't know a big butch lesbian if she saw one. Like, really? Because all of her friends were lesbians. And they weren't schoolgirl lesbians, they were working couples. They were classic glass closet lesbian couples. These people met at Wellesley, they met at Radcliffe, they met at Smith, they fell in love, and they lived together for the next 40 years. And that was her social circle.

And yet.

And yet mysteriously, when she said [to Lorena in a letter], "I long to kiss your lips in the southeast corner," she just meant like, hey, let's get a margarita at the bar, pal.

Other than just assuming these historians have so much internalized homophobia, what accounts for the fact that you have to fictionalize a story like this to get at what is almost certainly the real story?

Well, I think there are a couple pieces to that. One, I think one should never discount internalized homophobia--as they say, sometimes the simplest explanation is the most likely. But also, for historians who really adored and admired Franklin, there is something in that adoration and that hero worship of FDR which needs to be accompanied by a very particular narrative. And the narrative is, "He married Eleanor, it was a great meeting of the minds. He broke her heart when he had the affair with Lucy Rutherford, and Eleanor went on to become a great lady and a sainted doer of good deeds because she never recovered from her broken heart. And that's the story." That is not a story you have to dig for.

That's the popular narrative.

That is the American historical narrative. And it is part of the story about Franklin. Yes, he married Eleanor Roosevelt, it was a great meeting of the minds--although at the time most people thought that he had married up, and that she was a great catch--and then he broke her heart. And that is true. And then she went on to become a real progressive force in America, and she hated being First Lady, and she fell madly in love with Lorena Hickok. You can see how that story doesn't have quite the same narrative oomph.

Well--I wouldn't say it doesn't.

But [it doesn't] if the story for you is about the enormity and irresistibility of Franklin Roosevelt.

How did you research Lorena's life? How much were you able to?

If you want to see something that has heartbreaking amounts of internalized homophobia, you can read The Life of Lorena Hickok, E.R.'s Friend, by Doris Faber. It makes you weep. And in fact, I got it at a used bookstore in Northampton, and here is the inscription, I'll read it to you: "Dear Tony... I thought you might enjoy reading how the office struggles to turn a happy dyke relationship into a veil of frustrated heterosexuality. Quite a journalistic feat. Fortunately, dykes will triumph in the end, I'm so proud. Love, Marlieu." Which, I don't know who [these people] are, but I really like the inscription. A lot of people had looked at the letters. Lorena had done a little bit of writing about her own childhood. She had tried a few times to write an autobiography, and then you do get the basic facts. She did make clear that she had an incredibly difficult childhood. Born in South Dakota, father unsuccessful at one business after another, mother died when she was 13, she's raped by her father. She goes off to be a hired girl. Was taken in by her aunt, finishes high school, goes on to college, drops out and becomes a newspaper reporter. And at the point that she meets Eleanor, she is the most prominent female journalist in the United States. She has a byline in the New York Times. She's a hot ticket.

That was so exciting to read about, even separate from the love affair.

I mean, she also was not perfect. Creating fictional worlds, whether or not they are built on real characters, they're always built on something real. I mean, that's true even for science fiction writers. It is the fictional world that is built within real trees or real people, real elements. And that's the pleasure in it.

What is the most fiction-y part of this book? Was there something that you were like, "I'm just gonna make all that up"?

There is no information at all about this weekend in 1945, which is where the central action [that frames the novel] takes place. There's nothing written about that anywhere. There's one sentence in one biography that mentions her getting in touch with Hick after she leaves the White House, after Franklin's death. So that entire thing is fictional: How might that have gone? What is it like when you were lovers and you are not lovers, but you still love each other? At its heart, this is a novel. This is not a newspaper article with a few flourishes. This is how I have come to imagine these characters. I have researched them a great deal, but they are my versions. And my interest is more in truth than in facts--although if you like that kind of thing, there are a lot of facts in there. The piece that is wholly of my imagination entirely would be Lorena's side trip to the carnival, because there is an extended chunk of time where one has no idea what she has done with her life. So I let her do something that struck me as the kind of intrepid girl that she was, but also the kind of things that happened to people. You know, you turn right instead of left, and there you are in a completely unimaginable world.

Lorena Hickok in a 1941 portrait. (AP Photo)

Was there something that you learned in the research that you did that you were least looking forward to figuring out how to fit in? What was the most inconvenient truth?

There were things that were painful to come across, painful to perceive, painful to engage with. And a lot of that had to do with the enormous bouquet of prejudice and discrimination. There were not that many byways one could go down in history without going "Ow, ah shit. That's unfortunate." Whether it was about women, or Jews, or black people, or queer people. You really had your pick of very public, not so private, not so shame faced, overt acts of discrimination and dislike. And that was hard. And that was not confined to the bad guys.

Would Eleanor have made a better president than FDR?

I don't know. Louis Howe, who was FDR's great campaign manager for many years, wanted her to run. Very seriously, [and] basically proposed that he become her campaign manager and that she run for president as Franklin was ill. It might be that by the time Franklin died, she would have become a great president. She did not have his natural facility for wheeling and dealing. She wasn't made that way. So lying to people's faces, and telling them one thing at 9 am when you know in fact at noon you're going to say something else because you need to get a different result by 3, it was not her nature. She had a lot of principles and she had a lot of personal commitment. The process by which one turned overarching principles into actual policies, that you could get people to sign up for, I think would've been a challenge for her. Not to say I don't think it wouldn't have been great to have her as a president, because I do.

Did working on this book change how you think about the presidency?

I feel like I don't know what I was doing during American history in high school! It doesn't seem that I was in class. I missed quite a bit, so I feel like this is a real crash course in 20th century American history for me. And so there are a couple of things. There was an exceptional videotape of Nina Turner, who had been a state Senator in Ohio. And right after Trump's inauguration, she gave just a barn burner of a speech, on Martin Luther King Day [in 2017]. And she begins by saying, "We have been here before." And that is really my strong sense in reading the history, which is like, we have had terrible presidents. We have had presidents who have willfully misunderstood what was happening. We have had leadership in a country that was cowardly and morally culpable, willfully blind. This is not the first time, it won't be the last time. And also, that the viciousness and the hatred, and the visceral rage on the right, is nothing new. And although the object of their hatred moves in and out, the vitriol, the ignorance, the fearfulness and the rage, are utterly unchanged. And it is distressing that this is a significant strand, but it is also to me in some ways reassuring that this is not new. They are always with us. You think the poor are always with us, let me tell you that the enraged right are always with us.

Should anyone care who the president is sleeping with?

I always care, because I'm a snoopy person. And I like to know things. But aside from my own personal snoopiness, I suppose it depends on what you discover, and understanding what its meaning is. For example, do I care if Donald Trump slept with Stormy Daniels? Well, no, because it's certainly not telling me anything new. And it is not likely to overturn this presidency. And it does not in fact seem to me to be a different stance than the one he personally takes on the world. So those are the kind of things that make it interesting, right? When you have the Republican congressman caught with the page in the bathroom, who's been just blasting family values, well yes, that is worth knowing. So caring is a funny word, because it's like, what is it we're actually caring about? Did I care about Bill Clinton and his escapades? I did, because it really put a wrench in the work. And that was bad.

How do you describe your sexuality?

I describe myself as a queer woman. But the subject doesn't come up that much, you know. At the grocery store, they say, "Do you have your stop and shop card." But when it comes up that's what I would say.

Last night as I was rereading sections from the book, I turned to my wife and was like, "I'm a woman in my 40s who's been covering queer culture my whole career, and I'm having trouble thinking of other books or films that tell a really vivid story of what it is like to spend your life with a woman."

No kidding. I think there's a reason for that. And it's not that you're having short-term memory loss.

I felt really seen, as they say, as an old married lady. Why is this such a rare feeling?

Well, you know. I would think that the two words that really leap out in your remark would be old and lady. I'll tell you, there's a really nice thing Random House did with the hard copy--the end papers are cherry blossoms. And I was really emotionally touched by it, that they would say to themselves, "You know what? Those cherry blossoms really figure in. It is part of their symbol, Lorena's and Eleanor's, for the giddy days of love, and also this sense that it doesn't matter if the blossoms fall and wither and go away, and it's another season." I just loved that they put the cherry blossoms on the end papers. And I think it's the same kind of response that you have to the book, which is that we do not get that many portraits of life as it is lived by people or a wide range of people. And maybe a willingness to go on looking, rather than to end the story at the shimmering apex. We're certainly past the days where somebody is going to have to throw themselves into the sea in despair about being a queer, so that's good. You're not going to see that story so often anymore. But the idea that there's this long love between two women, that rewards looking, rewards reading. Maybe it's just not that common.