"We were being slaughtered by schoolkids." In the late 1970s, this was a widespread feeling among many people in the Montrose district of Houston. Each summer, dozens of restless teenage boys would spend their nights cruising Lower Westheimer Road, looking to beat up queers. Many drove in from Houston's affluent suburbs. Most had issues with their own sexual identities that they somehow thought could be resolved by assaulting another man.

They came two, three, and four at a time, armed with bats and tire irons. Some came with knives and guns.

As with other towns and cities across America, the emergence of a center for gay life in Houston still felt novel. The Montrose was an older, quiet, tree-lined neighborhood adjacent to downtown, home largely to aging widows and empty nesters. Then as the '60s ticked over into the '70s the hippies arrived, embracing the Montrose's rare combination of character, walkable streets, and low rent. The area quickly became the center of Houston's counterculture. Gay men soon followed. By the middle of the decade more than a dozen gay bars had opened in the Montrose as well as bathhouses and adult bookstores.

Gays in Houston finally had a sense of community and a place to call home, but in a way they'd also painted bull's-eyes on their backs. The queer bashers now had a clear destination, and street punks had a large and centralized population on which to prey.

Jim Shepard learned about the Montrose the hard way. Just after midnight on June 23, 1979, he was walking home from the Silver Phoenix disco when three teens in a pickup truck pulled over and asked if he wanted to smoke a joint. Shepard got into the truck with them and suggested they go to his apartment, but the teens insisted on driving to Memorial Park instead. After they parked the truck and stepped out onto the grass, the tire irons appeared and the beating began.

"I'm not a weak or small person," Shepard says, "but I didn't fight back. I pleaded with them to stop. They didn't."

The attackers alternated between repeatedly pummeling his head and savagely kicking the rest of his body. Finally, in what was obviously intended to be a kill shot, the ringleader rammed his iron into Shepard's forehead. The three men then drove away.

Shepard was badly bruised, and had several broken ribs, and the final blow had smashed through his skull and torn into his brain tissue. But he survived. Unable to stand or use his arms, he managed to crawl to Memorial Drive and flag a passing car. Three hours of emergency brain surgery, several days in intensive care, and six months of recovery followed.

Unfortunately, victims like Shepard could count on little help from the police. While community leaders pleaded for foot patrols in the Montrose, HPD chief Harry Caldwell maintained they lacked the manpower--though somehow he could always pull together a dozen officers for a raid on a gay bar. In the first half of 1979 there had been 10 unsolved murders of gay men in the Montrose, but Caldwell claimed the crime statistics didn't warrant increased policing.

The truth was that violent crimes against gay men in Houston were grossly underreported. The harassment and beatings men received at the hands of the police were often as bad as those dished out by the thugs on the street. If it was something they could walk away from, many didn't even bother calling the cops.

But Shepard's assailants didn't get away. Jim Erwin, the manager at Dirty Sally's bar, had seen them lure him into the truck and had written down its plate number. When the details of the beating surfaced, he went to the police.

All three were caught and convicted. The 16-year-old ringleader confessed to several similar beatings. All three were released on probation.

Erwin knew something had to be done. It was time to stop saying, "Somebody should do something," and start saying, "We're gonna do something."

Others had tried to mount citizens' patrols in the past, but no one was willing to devote the time, effort, or funding. But Erwin had a strong ally in his friend Steve Coates, a law school student and natural organizer with a talent for motivating people. Also on his side was Andy Mills, the manager of iconic gay hangout Mary's Lounge and president of the Houston Tavern Guild, an organization of Montrose bar owners that had formed to protect their common interests.

On Sunday afternoon, August 5, at a town hall meeting of Houston's Gay Political Caucus, Coates and Erwin announced the formation of the Montrose Patrol and invited anyone interested to join them. Many in the community didn't know what to make of the announcement. Upfront, a gay-oriented newspaper, warned that "a group of unidentified men" were plotting to launch "an armed secret force." Activist Ray Hill met with TV and news people and informed them that "since police protection has not been adequate, gays have organized their own vigilante force."

But vigilante justice was not what Coates and Erwin had in mind. Instead, their idea was to work with the police. They'd watch over the neighborhood, report any crimes to the HPD, and take action themselves only when needed to protect community members.

"Steve Coates, Jim Erwin, myself, and a few others all had an interest in law enforcement," recalls Greg Wheeler, a founding Patrol member, "but we were either too young, too old, going to college, or couldn't pass the pre-employment polygraph. Remember, back then it was a class C misdemeanor to be gay. So this was our way to help our community and fulfill the desire to be in law enforcement."

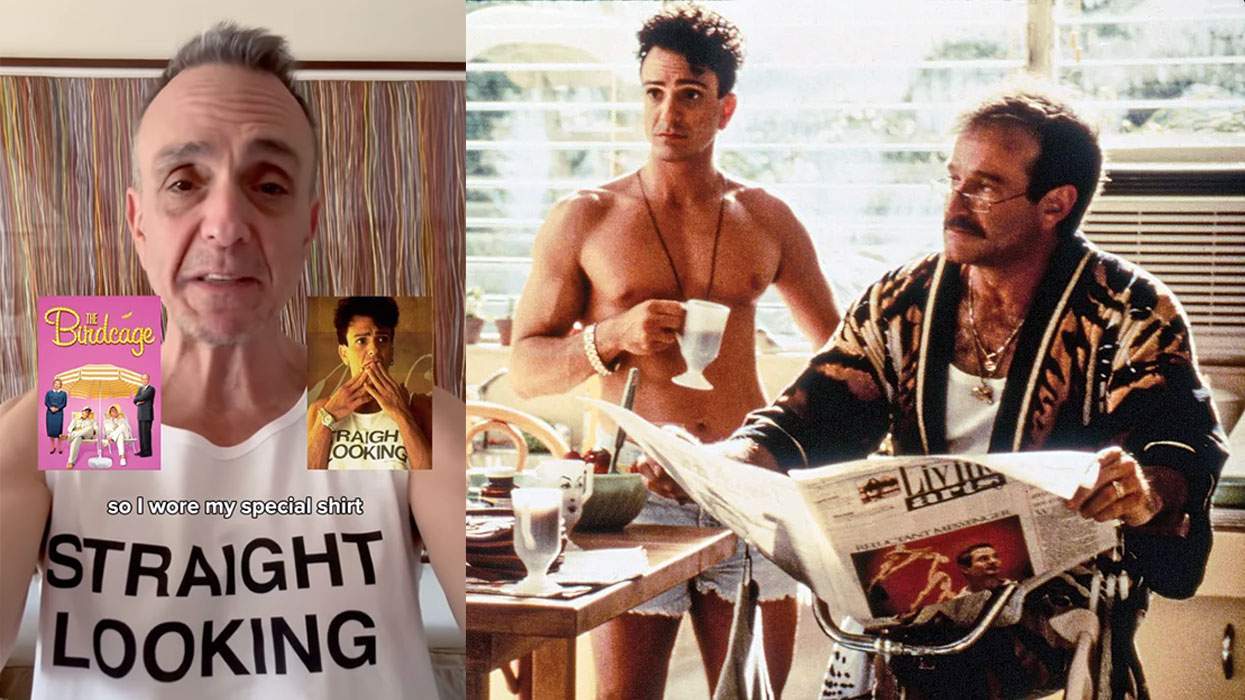

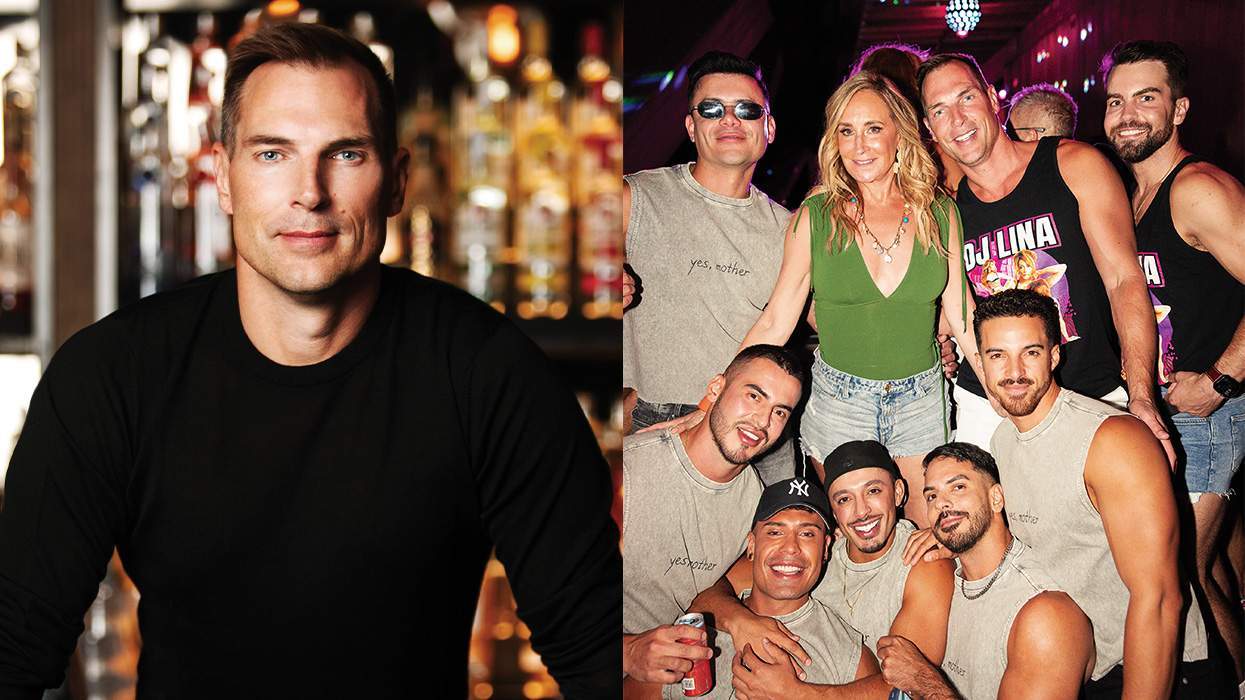

Photography: J.D. Doyle

The Tavern Guild chipped in start-up funds of a few hundred dollars for radios and gasoline. The group met each Friday, Saturday, and Sunday evening at Mary's to organize the night's activities before going out on patrol, in cars and on foot. They kept in touch by CB radio and walkie-talkie, with Coates insisting that everyone check in each half hour.

Their only weapons were spotlights and whistles. Some on foot patrol brought large dogs. "We weren't big bodybuilders," says Wheeler, "but several of us were trained in, let's just say, 'special skills and tactics.' Since we couldn't legally detain a suspect, we found creative ways to deter and delay until the HPD could arrive."

On a typical night, 20 or 30 men and women would be out on patrol from 10 p.m. until the streets were clear. Most nights, that meant until dawn.

In its first month of operation, the Patrol intervened in more than 40 attempted beatings, in each case neutralizing the threat before any community member was hurt. Its success was quickly embraced by the once-leery Gay Political Caucus and gay-oriented newspapers as well as the mainstream media. The ranks of volunteers swelled.

"If somebody was causing a ruckus in a restaurant, or if they found somebody passed out in the bushes, they'd call us in," says Roy Robinson, a Patrol supervisor. "Nobody wanted to call the police. Either they wouldn't show up, or they'd end up taking somebody to jail."

Even the police warmed up to the Patrol, at least in the public eye. Chief Caldwell says he welcomed their assistance, and two units carried Montrose Patrol radios. Response times to calls from the Patrol were often one minute or less. Behind the scenes, however, certain officers were trying to sabotage the spirit of cooperation between the Patrol and the HPD.

Communications broke down completely when the CB channel they used was discovered by the public. Suddenly the air was filled with homophobic taunts. With their radios rendered useless, it became nearly impossible to pass information or summon help.

An FM repeater system would come to the rescue. Licensing was required and FCC rules of use were strict, so not just anyone could break in and disrupt the airwaves. But the price tag was $17,000. Coates laid the groundwork by filing the Montrose Patrol with the State of Texas as a nonprofit corporation, headquartered at Mary's Lounge.

The entire community gave support, with several bars and organizations hosting fundraisers. Wheeler remembers the community-wide effort. "There was a sales manager at E.F. Johnson Technologies who got us our radios. He was also one of the better-known drag performers of the time. He and his drag queen friends did a lot to raise money for the Patrol."

The Family, a then-recently formed community service group, donated space in their center, giving the Patrol a 24-hour home base. With their FM radio system in place, Coates became the Patrol's dispatcher, supporting four mobile units and a dozen walkie-talkies, and--to keep the police honest--recording all phone calls and radio traffic on reel-to-reel tape.

"We'd go to the office to get in the air-conditioning," Robinson says. "In Houston it can be 90 degrees in the middle of the night. Steve would be there running the radio. He always had a big cooler of cold drinks. He'd get us Cokes and get us fired up to go back out on the street."

In early 1980, Caldwell resigned as chief of the HPD. Mounting pressures from a massive swell in the city's population as well as hundreds of abuse charges made by gay, black, and Latino communities had taken their toll. The Montrose rejoiced and waited for his successor to be named.

Nine representatives of the gay community, including Coates, were invited by Mayor Jim McConn to meet with assistant chief Bradley Johnson, his designee for the job. Their hopes turned sour when Johnson appeared on a talk radio show hours before the meeting and declared he was "violently opposed" to homosexuality. It became clear that the relationship between the gay community and the HPD would not improve.

Still, 1980 was a hopeful time. Street violence in the Montrose had decreased, thanks to the Patrol's involvement. The gay community had become a significant political force in Houston; candidates now sought out the endorsement of the Gay Political Caucus rather than shunning it for fear of backlash.

That year, the Patrol was asked to provide security for Houston's Gay Pride Parade, in cooperation with the police. The previous year, the HPD had assigned only eight officers, but this time it promised a contingent of 57. The plan was for the Patrol and the HPD to lead the parade together.

Then on Friday, June 20, on the eve of Houston's Pride Week, the police staged a massive raid at Mary's. Fifteen officers entered just after midnight and arrested 61 of the roughly 90 patrons in the bar, including manager Mills and owner Jim Farmer, one of the grand marshals of the Pride Parade. Most were charged with public intoxication, even though some had yet to finish a single beer. It was the third year in a row that a major raid had occurred on the eve of Pride Week.

"Some of us felt the HPD was telling the community there would be no more cooperation," Wheeler recalls.

Outside, police vans waited, with TV news crews and firefighters with hoses at the ready. The HPD was expecting--maybe hoping for--a riot that would provide an excuse for canceling the parade and closing down Mary's permanently. The attempt to provoke the gay community to violence on camera backfired, as the victims of the raid maintained calm, and all three networks reported on the bullying tactics of police.

One week later, at 2:30 a.m. on a Saturday, less than 36 hours before the parade was to begin, Fred Paez, the secretary of the Gay Political Caucus, was killed with a single gunshot to the back of the head at close range by off-duty HPD officer Kevin McCoy.

McCoy was providing nighttime security at a warehouse near the city bus garage where Paez worked. He claimed he was in the process of arresting Paez for public lewdness--specifically, fondling McCoy's crotch--when Paez attempted to grab his gun and it accidentally fired. Another off-duty officer on the scene, "hanging out" with his buddy McCoy, backed up the story. No one could explain why they had strolled with Paez to the dark side of the building, why a firearm had been aimed at the back of Paez's head for a class C misdemeanor arrest, or why the safety catch was off.

The Pride Committee held an emergency meeting. They feared the riot that Mary's had avoided would erupt at the parade, but on a much larger scale; 20,000 were expected to attend. Gay community leaders decided to downplay the news of Paez's killing and hold back some of the details until they'd made it through the weekend safely.

The Montrose Patrol responded in full force. In addition to leading the parade, members rode floats in the middle and at the rear. More were stationed on rooftops or in the crowd along the two-mile route. To bolster their ranks, members of gay community service organizations were "deputized" and sworn in as auxiliary Patrol members for the day.

Says Pride Parade committee member Tony Vega, "The police they assigned to the parade had been informed about what happened, and they promised they'd be sensitive to the situation. They seemed a lot more nervous than the members of the Montrose Patrol were."

The parade proceeded peacefully. Many participants wore black armbands, and some distributed leaflets demanding a thorough investigation of the "accident."

The raid on Mary's and the killing of Paez had far-reaching effects on the community. Several bar owners had chipped in to post bail for those arrested, with Farmer picking up the tab for 37 people. Trials went on for over two months; court costs hit the thousands.

With Mills's tenure as Tavern Guild president at an end, Mary's close to bankruptcy, and all of the Montrose bars feeling the pinch, no one had any funds to spare for the Patrol. Bars and businesses set out contribution cans, which pulled in barely enough to cover administrative expenses, with nothing left over to reimburse drivers for gasoline. Patrol membership dwindled, from 50 volunteers at the beginning of the year to around 20 by the fall.

Many now seemed complacent because of the Patrol's success. Few high school boys went to the Montrose looking for trouble anymore. Police harassment of gay businesses also dropped after the Mary's raid; between the negative TV coverage and pressure from Mayor McConn and U.S. Congressman Mickey Leland, the HPD realized it went too far.

When McCoy was indicted by a grand jury and became the first Houston cop ever to face charges in the shooting of a gay man, even the officers on the street knew it was time to tread lightly.

But street crime in the Montrose was still a major issue. Over a two-week period beginning in late September, a single pair of muggers began a crime spree that snagged more than 20 victims a night, all of them hit from behind, beaten, and robbed at gunpoint. The police had no effective response.

Montrose businesses rallied once more and hosted a new round of fundraisers that raked in thousands of dollars. Suddenly flush with enough funds to keep going through the spring and with a fresh crop of new volunteers on the street, the Patrol reorganized early in 1981, moved out of the Family Center, rented its own space, and hired a small office staff.

That September, McCoy finally went to trial and was found not guilty in the death of Paez. The HPD took it as a vote of confidence, and a day later, the raids began. A swarm of officers in gay hustler drag flooded the district, targeting men in bars, in bookstores, and on the streets.

"The worst thing that came out of the Fred Paez trial," says city councilman George Greanias, "was the signal some police officers got that from now on they were under no real restraints when dealing with the gay community."

Bar owners soon discovered that those who hired off-duty police officers as security--at rates well above their regular pay--would avoid police raids. Faced with a choice between keeping the streets safe or keeping their businesses open, most opted to protect their own livelihood.

Houston's gay community organizations and media helped make a last-ditch effort to keep the Patrol afloat by appealing directly to the public for donations and more volunteers, but without the support of the bar owners, it was impossible to make ends meet.

In April of 1982, having been unable to pay the rent on its offices since December, the Patrol was served an eviction notice. The group was forced to disband. The members dispersed, and the radio equipment disappeared.

But Houston was changing. Kathy Whitmire, a friend to the gay community, had won the November election and taken office as the city's new mayor. Johnson immediately resigned as chief of police, and Whitmire named as his replacement Lee P. Brown, the public safety commissioner of Atlanta, known for building a good relationship with that city's gay community. During Brown's tenure as chief he made violent street crime a top priority, brought gay men and women onto the force, and improved relations between the police and all of the city's diverse communities.

The Montrose Patrol had emerged at a time when gay rights were ignored and more often derided, a time when gay men and women faced arrest simply for being who they were, and risked beatings and even murder for walking in their own neighborhood. But it would not survive to become part of Houston's new cityscape.

In 32 months on the job, the Patrol prevented crimes, saved lives, and became the very first gay organization to achieve any sort of cooperation with the police. Above all, it made the LGBT community in Houston believe that at long last someone was there to look out for them.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.