This Sunday, RENT will join Hairspray, Grease, and other timeless Broadway musicals, when it airs live and on FOX, once more bringing together eight friends who shook the American zeitgeist in the mid-'90s.

Most notable among the characters from RENT is the colorful Angel Dumott Schunard, the percussionist drag queen who enters the posse on the night the story begins and functions as a mascot of sorts for the then-edgy musical and its carpe-diem message. Instantly with her dramatic entrance, clad in glittery red lipstick, an ostentatious Mrs. Claus getup, and classic Pleaser pumps, she easily becomes the most likable character in Rent. She has the biggest heart in the group (despite the canine homicide she admits to in her first minutes on stage) and also as the group's only gender-nonconforming individual is incidentally the play's only casualty to AIDS. Angel's imprint on pop culture in the '90s was a huge victory for positive representation in media for drag queens for a generation who narrowly missed the splendor of early RuPaul. Within a closer -- and queerer -- investigation of the details of her character lies evidence however that such a victory never belonged to drag queens to begin with.

Over the years, the perception of the character among queer fans of the musical has transformed into a heated conversation about her identity. Angel is written by composer Jonathan Larson into RENT's libretto as a drag queen, and is referred to that way by Mark, the play's narrator. And she certainly looks and acts like a drag queen, dancing and kicking in 8-inch heels with every line.

However, as queer identity politics has become more complex, so has the general perception of Angel being a drag queen.

Granted, Angel was written at a time in which less language existed, slower conversations amongst academics, and fewer empirical reasons to distinguish one's own gender identity-- after all, what did it matter how one identified when they were preoccupied with the ever-enduring threat of harassment and street violence? Even so, Angel's daily experience looks very little like a drag queen's. Angel presents fully en femme for seemingly mundane occasions; she hangs out in Mark and Roger's apartment in full drag, she's at the AIDS "life support" meeting in full drag, and most notably, she's in full drag as she engages in intimacy on a date with her new lover, Tom Collins. There's good reason to interpret Angel's expression not as being a drag queen who is seen both in and out of costume, but instead as a trans woman (or something like one).

Though now-legendary New York City drag queens certainly roamed the East Village in the '90s, they had their own scene. The gay nightlife hub, the Pyramid Club, was overrun by drag queens and shows nightly, and was in its prime at the time that Rent was first staged, and situated mere blocks from the musical's setting. It would have been rare for a queen to adopt her conspicuous drag persona as a daily lifestyle. Getting in drag like Angel's is immensely time-intensive and hard on the body, and yet on she goes in that getup performing her life's mundane tasks and engaging in intimate friendships with straight people, suggesting she has an immense personal cause for doing so. After all, with her full-time commitment to the family she found in the characters of RENT, there's no evidence she had any connection to the club or the Wigstock girls at all.

Echoing the societal silencing of so many gender-nonconforming people before and after her, Angel is given very little opportunity to speak for her own identity. The most we get from her is, "I was a boy scout once... and a brownie, until some brat got scared!" Perhaps the strongest affirmation of her gender identity we hear post-mortem from Mimi, who recounts a story during Angel's funeral about a time she clapped back at a homophobe skinhead by saying she was "More of a man than you'll ever be and more of a woman you'll ever get."

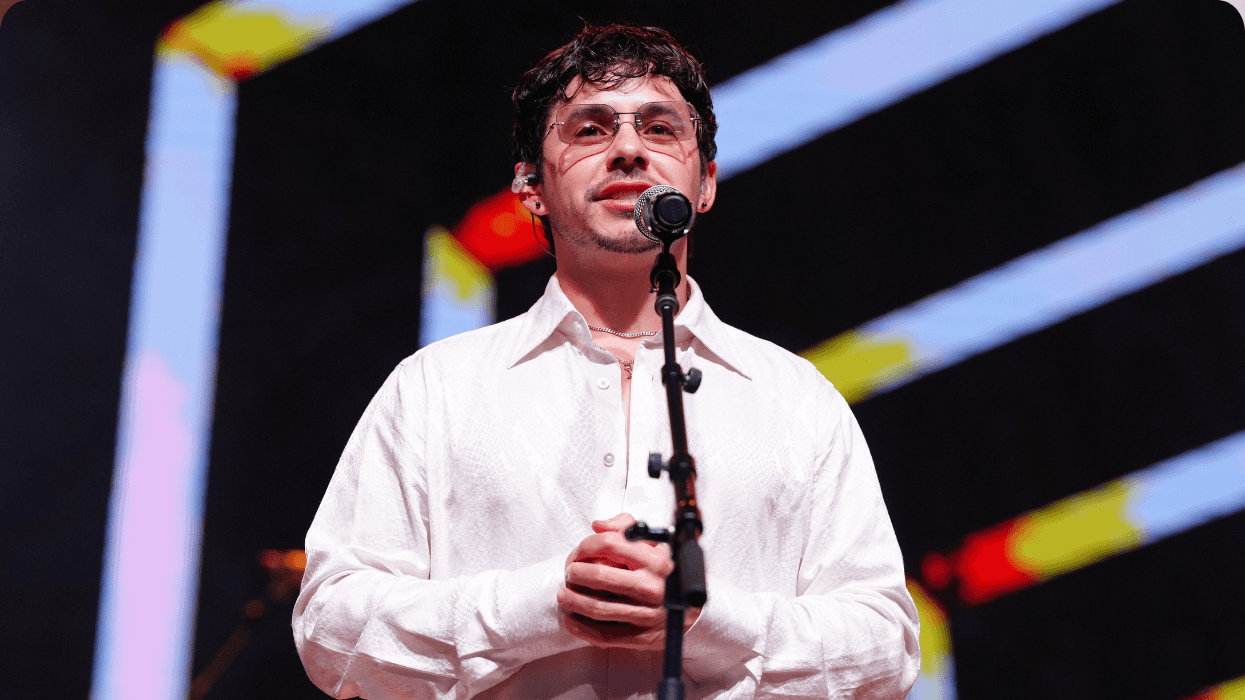

Angel's commitment to her femininity is absolute, and her friends never refer to her using 'he/him/his' pronouns until after her death. In the fan favorite number "I'll Cover You," a profession of love between Tom Collins and Angel, Collins lovingly croons to his adorned sweetheart saying "You'll be my queen/ and I'll be your mote." Within the context clues and the few words we have directly from Angel about her identity, we can surmise that her gender lies somewhere on the spectrum of what we know today as nonbinary. In this case, Angel and Valentina (who will be playing her this Sunday on Fox) actually have that in common, as with more than a handful of Valentina's RuPaul's Drag Race contemporaries.

As loud, clear and outward Angel's expression of self was in her life, what makes Angel's friends so confused about her identity in the wake of her death? Mark, retelling an anecdote about Angel's graciousness at her funeral, corrects himself from using 'he' to 'she' as though to adhere to her preference out of respect for the dead. However, once the argument begins after the funeral, Collins tries to quell the friends by saying "I can't believe he's gone" effectively reneging all of the femme-affirming and downright goddess-worshipping he showered on Angel during her life. Why would these inconsistencies exist when the only time Angel appears out of drag is on her deathbed, her impending consumption from AIDS making her physically unable to apply her famous glitter lip.

As a body of work, RENT festers with questions and plot holes notwithstanding the character of Angel, as its book and score are frozen in time as its composer Jonathan Larson suddenly died as the show was opening in 1995 at New York's Theater Workshop. In a way, the final product of RENT, which we will see televised with a contemporary cast all these years later is still a work in progress. The polish that a full run of workshops and previews would've afforded Rent could have perhaps smoothed out confusion about Angel (and countless other unanswered questions). Larson's death, however, is woven into the lore of the show, its rough workshop feel matching the grittiness of its content. Where clarity that would've come from the production process was sacrificed, instead sparked national intrigue and RENT mania in the 90s, and priming the show's visibility for its eventual Pulitzer Prize.

Due to RENT's then-edgy content, the reputation of exposure of queerness, and an early depiction of HIV/AIDS in popular culture, Jonathan Larson is often misremembered as a queer person who died due to complications from AIDS. In fact, he was straight and died from an aneurysm as a complication of Marfan syndrome, a lifelong health struggle of his. Larson has reportedly previously claimed the apartment he shared with friends on Manhattan's west side and supposedly inspired RENT, but it's generally understood that no known queer people lived there. It's likely Larson called her a drag queen because he couldn't distinguish a drag queen from and trans woman himself, and diagnosed Angel and her friends with AIDS not because he was personally immersed in the crisis, but rather that he needed a contemporary blight to match the tuberculosis of the Puccini opera La Boheme, upon which RENT's story is loosely based.

Larson's untimely death froze Angel somewhere in gender limbo and left RENTheads perplexed for decades to come. Indeed, however, Jonathan Larson's writing about queer characters is conjecture akin to Michael Crichton writing about dinosaurs, rendering any attempts to answer the questions about Angel's identity (What does Collins insistence that he 'likes boys' say about Angel? Why is it even plausible that lovers in a queer romance surround themselves exclusively with messy straight people?) an exercise in futility. It's highly likely even that the characters of Angel and Collins are doubly removed from Larson's personal experience; queer author Sarah Schulman has suggested with compelling evidence that the characters are plagiarized from her 1990 novel, People in Trouble.

As Valentina struts into the boys' loft on Avenue A, so will follow the questions that arise from confused queers about one of pop culture's most visible fictional drag queens. As we've seen from nearly 11 seasons of Drag Race, queens and otherwise-gender-bending characters on television increase queer visibility in exponential and unprecedented ways. Whereas the confusion about Angel's identity sparks critical dialogue within the now-adult queer community, RENT Live will still however undoubtedly resonate primarily with young viewers as it did two decades ago. The charm, and empathy that Angel's character inspires among RENT's audience will give the television audience another drag queen to adore. While Drag Race has done so 126-fold, transfeminine characters on television today are still mostly relegated to street-based sex workers or charlatan women "tricking" straight men. RENT misses an opportunity to positively represent trans women and full-time gender nonconforming individuals by virtue of being written by straight man who didn't actually know enough drag queens or trans people to distinguish between them, and in leaving one of Broadway's most beloved characters in a gender limbo, leaves young trans girls disinherited of her glory.