I was 12 when I got my first typewriter, which was actually my last typewriter, too. Word processors, and then computers, would soon put the typewriter out of business. You have to work hard to find reasons to mourn the endless fiddling with typewriter ribbon and sticky keys and recalcitrant carriage returns.

And yet. That typewriter carried me all the way through my teens, as I edited one magazine after another--samizdat-style publications in my village, student newspapers at college, and then into Bosnia along mountain passes in the spring of 1993 on my first foreign assignment for a real, grown-up paper. Today the idea of running around Sarajevo's bombed-out streets with what was essentially a child's typewriter seems preposterous, and yet there it was by my side, again and again.

It was there in Berlin, a year later, as I sat up through the night to meet a morning deadline for a story to mark the fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. A year later--Christmas Eve, 1995--and I was with my typewriter again, this time in Bethlehem to witness the arrival of PLO leader Yasser Arafat, the last gasp, it would turn out, of the unraveling peace process in the Middle East. Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin had been assassinated by a Jewish zealot less than two months earlier. I wrote that story, too, fighting back tears all the while.

Sometimes I have to remind myself that all these things happened in my 20s, when I was at my most idealistic, my most passionate, my hungriest. It is natural to want to ascribe noble principles to what we do, but as long as there has been a press, there have been journalists motivated by wanting to document the world as they find it--even, and perhaps especially, when that involves speaking truth to power. But the media is in a shaky place. I'm not sure how many 20-year-olds would get those same opportunities today.

Newspapers continue to close, while others lay off reporters in round after round. Public faith in the press is at an all-time low. Some of that is our own doing--the failure to ask the right questions in the run-up to the Iraq War gave succor to those who believe the media is complicit in maintaining the status quo. It gave credibility to claims by people like Donald Trump that the media is just part of the establishment, a perception that unites left and right in a way that few other bogey monsters do. Instead, Trump turns to social media, where the press will always struggle to be heard, much less respected.

A reporter on Twitter is just one out of 313 million people, many of them too busy listening to their own echo to catch someone else's. Yes, Twitter represents a meritocracy that has brought exposure to underexposed issues like police brutality, but it's also a cacophony. And because that's where the eyeballs are, that's where the media must try to follow. More often than not, young journalists today are taught that their first priority is to generate traffic, but since no web site can ever have enough traffic, the pressure never ends. Young journalists might still earn praise for writing good stories, but more likely they're judged on meeting targets. The media is berated for creating "clickbait" stories, and yet clickbait is what advertisers demand. No wonder the public has lost faith in journalists. We've lost faith in ourselves. And because most people already consider the press to be scum, a presidential candidate can get away with condoning violence against reporters, because who doesn't wish they could punch a reporter? No wonder Trump admires Vladimir Putin. Both men are determined to turn the press into an irrelevancy, and with their fists if necessary.

There are still great journalists doing great work, but I often find myself wishing George Orwell, the greatest of them all, were still alive to shine a light on these peculiar times. He was a writer who thought nothing of putting his life on the line, whether to experience the fight against fascists in Spain, or to live as a tramp in London and Paris, cold, hungry, but still as shrewd an observer of human nature as you could find. "Good prose is like a window pane," he wrote, an observation as true today as ever. But I also can't imagine where a writer like Orwell would find space for his kind of writing today. I wish I still had that old typewriter, not for what I could do with it now, but for what it represented back then: The power of words. The thrill of the chase. The romantic delusion that a good story, well told, could change the world.

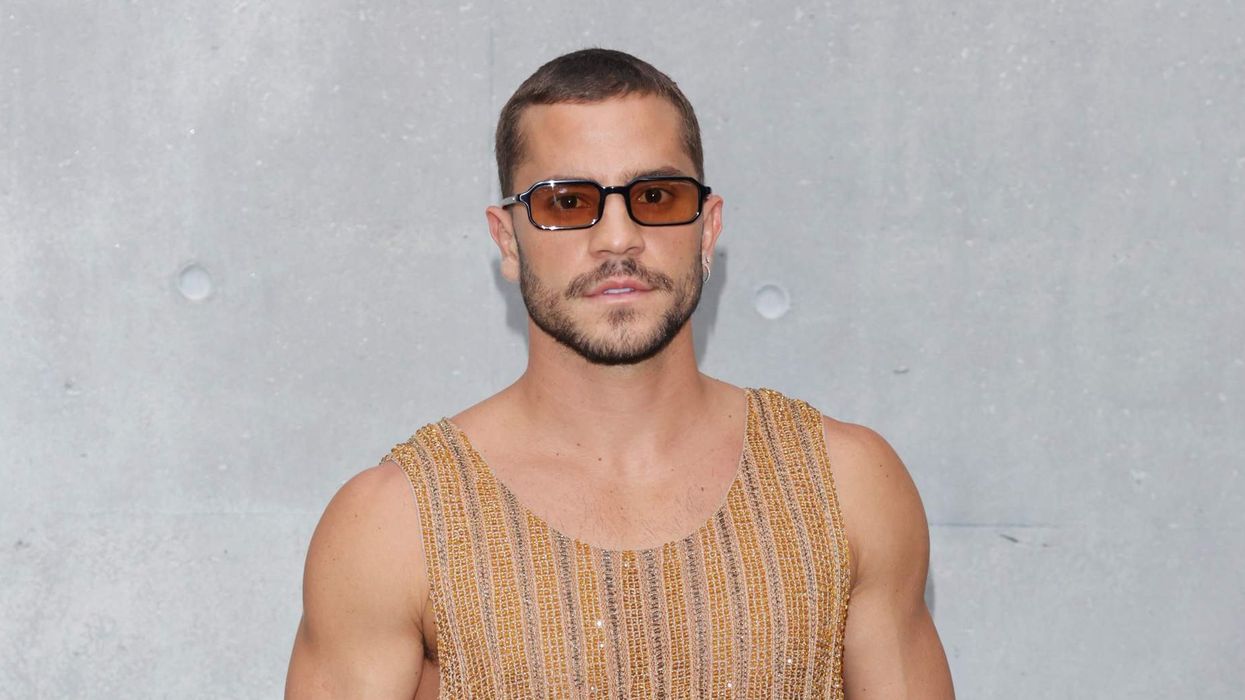

Aaron Hicklin is the editor in chief of Out.