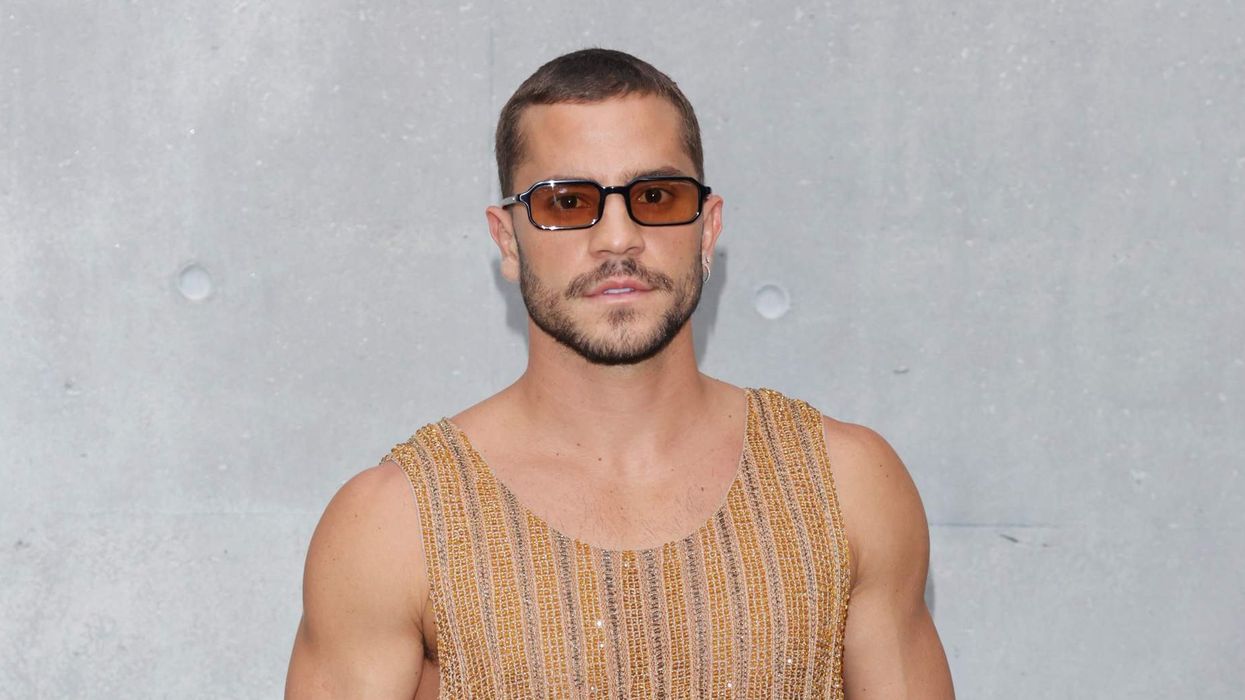

Photography by David Gray

Ichabod Crowley intends to complete his physical transformation as soon as possible. In the coming years, he plans to continue with hormone therapy and proceed to the surgical removal of his breasts, as well as possibly altering his labia and masculinizing his clitoris. But when it comes to phalloplasty, the surgical fabrication of a new penis, Crowley says, "I'm on the fence."

It isn't that he doesn't want a penis. For Crowley, a 29-year-old transgender man from Ohio, having a penis would be the holy grail of his transition. He says the main barriers to the surgery, aside from the $80,000 price tag, are uncertainty about the results and the risk it involves.

Dr. Loren Schechter, a plastic surgeon who has performed female-to-male confirmation surgeries for over a decade, estimates that complications, specifically with issues related to urination, can arise in 30% to 50% of cases. Even if all goes well, a sculpted phallus might be a far cry from a realistic penis. "If I end up looking at a little pink skin sock at my groin, not only may I feel incomplete, but I'll think, Oh my God, I'm mangled," Crowley says.

Now that barrier might be eroding because of funding from an unlikely source. The United States Department of Defense has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into research on creating genitalia and looking for alternatives to phalloplasty. The military wants to heal warriors returning from Iraq and Afghanistan who suffer from grave genital injury. Modern body armor can keep soldiers alive in the face of an improvised explosive device by shielding their chests and abdomens. "Now you're seeing shifts of injuries toward extremities and genitalia," Schechter says. There are nearly 1,300 veterans who've returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with devastating injuries to their groin area and genitalia. Military doctors have called these some of the "most severe, destructive" injuries they've seen.

Aside from the severity of these injuries, it's just not easy to reconstruct a penis. A phalloplasty, Schechter says, is a more surgically complex operation than vaginal reconstruction. As the saying goes, it's harder to build a pole than dig a hole. Part of the reason for that is simple: Penises are bigger than clitorises.

When it comes to phalloplasty, Schechter says, "We need to bring in additional tissue." Surgeons harvest skin from the mouth and the forearm, back, or thigh -- doubling the risk of infection. The surgeon sculpts that tissue into a penis and connects nerves and blood vessels between the patient's groin and the new organ. Finally, the urethra needs to be extended through the penis as well, a delicate procedure that leads to the most common source of complications.

It takes more than one surgery to complete a phalloplasty, too. Alteration of the existing genitalia needs to happen first -- things like removing the clitoral hood -- before the penis can be built. Finally, if a patient wants to use the penis for sex, surgeons install an erectile prosthesis that can pump the penis up. "No device will last forever," Schechter says, and these prostheses usually need to be replaced every five to 10 years.

Crowley says that's one of the most terrifying things about phalloplasty. He doesn't want to have to go through surgeries periodically throughout his life. And he says, "It would be bad enough if you were a man and your dick broke during sex. What if you're a trans man and suddenly your dick explodes? Then what do you do?" More surgeries.

So the military is throwing money at new methods that could cut down on those risks and give soldiers a whole organ. The biggest contender is in an experimental field called regenerative medicine: the lab-grown organ. Dr. Anthony Atala, the director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C., started experimenting with bioengineered penises in 1992. Sixteen years later, his research started bearing fruit. His lab gave 12 rabbits lab-grown penises, and four of them made babies. Around the same time, the lab was successfully regenerating vaginas for four women -- work that would show that bioengineered genitalia were a possibility for humans. Scientists are hoping to repeat the feat with a human penis.

The other option might be to transplant a penis the way a surgeon might transplant a heart or liver. This is relatively straightforward, but, apart from a recent, reportedly successful case in South Africa, it's only been attempted once. Chinese surgeons achieved the first penis transplant in 2006, but they had to remove it a couple of weeks later because the patient and his wife said the new penis was causing them too much psychological distress. Since the patient didn't have the organ for very long, it's hard to tell if any critical complications would have arisen over his lifetime.

"My personal feeling is that regenerative medicine will probably hold more promise than transplantation," says Schechter. There are two main issues with transplantation. There's the lack of a donor pool, and there's the risk of the patient's body attacking the foreign penis. Immunosuppressant drugs can lead to increased disease susceptibility, and over time to cancer or kidney or liver damage.

A lab-grown penis, Schechter says, skirts all these issues because tissues from the patient himself would seed the growth of the organ. So the patient's immune system won't look at the new penis and try to destroy it as foreign material, and the patient himself might feel a stronger connection to the new organ.

What's more, a phalloplasty is a sculpture; it's an imitation and not always a great one. A lab-grown penis would be real. It's almost the perfect solution.

Researchers looking into bioengineered penises haven't really begun thinking about how they might grow one for a trans male because, with current technology, it's impossible. People born with female bodies don't have penile erectile tissue cells, which scientists need from the patient if they're going to grow a complete, functioning penis in the lab. Mostly, lab-grown penises are being researched to heal trauma from injuries like the kind soldiers experience or cancer or birth defects.

Science might still find a way to grow penises for trans men, but it'll take many years -- maybe many decades. Schechter says that at the very least, basic surgical techniques will continue to improve as doctors find better ways to connect tissues and nerves and increase sensitivity. The military medicine is helping with that. "But I don't see anything on the immediate horizon that will revolutionize it," he says, speaking of female-to-male confirmation surgery. "My guess is that over time, as we continue to expand our knowledge and understanding, techniques will improve."

But that might take too long for Ichabod Crowley. He wants to have these surgeries done in the next few years, if possible. Like many trans men he knows, he says he feels incomplete and abnormal without a penis. "There are times when I'll reach down, and it won't be there. I get very, very confused for about a minute until I go, Oh, right."

Psychiatrists say "gender dysphoria" is the pain of being born in the wrong body. Crowley says that's the toughest part of his life. "I have PTSD. I have anxiety. I was physically, sexually, and mentally abused throughout my childhood. The pain I feel through dysphoria is worse than all of that. And there are a lot of transgender people who just end it."

Crowley says he probably would take the phalloplasty and the prosthesis, even with all of the risks and downsides, just to help with the pain and feel more whole. Having anything between his legs would make him feel better. "I know I just feel more confident when I go out and I have my packer on."

Crowley says he was at a local gay bar one evening. A man walked up to him and the owners and began lodging what he called a "formal complaint." Crowley recalls it all perfectly: "He goes, 'This is a men's gay bar. There are women here. There are lesbians at this gay bar.' " I just looked at him, and I pulled out my packer, and I waved it at him, and I went, 'Suck it.' I got a bit of a rap for that one..."

He trails off and laughs. It's not quite the same as an actual dick, and he knows it. He might not ever have anything more than a plastic packer in his pants, but he's holding on to hope that medical technology will one day make it possible for people like him to have real erectile tissue, real semen -- a real penis to whip out as proof.

The Battle to Replicate the Body’s Most Complex Organ

Military money for plastic surgery and urology is funding innovations in genital reconstruction. But can that benefit transgender men?