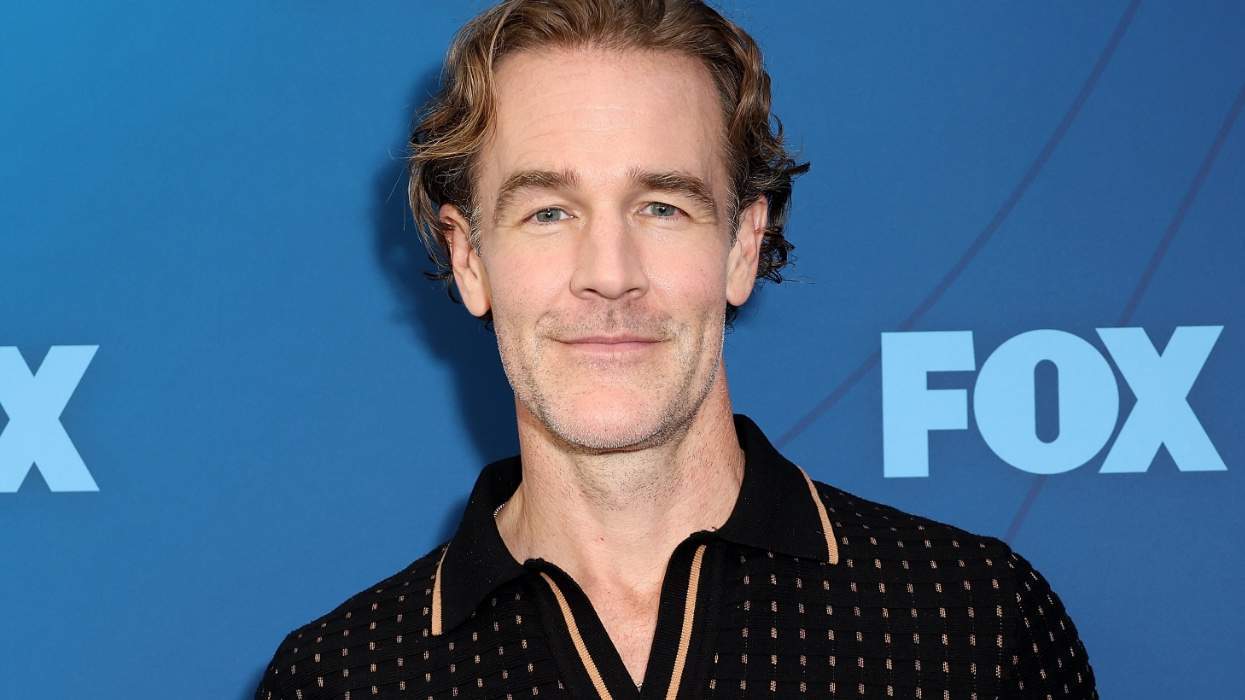

Photo of Markus Schleinzer courtesy Strand Releasing

When a review copy of director Markus Schleinzer's first film, Michael, appeared in my mailbox, I put on the DVD without bothering to look at the publicity material. Ninety-six minutes later, I was in deep shock. Michael had crept into my subconscious and started an inner dialogue that has yet to end.

The eponymous "hero" of Michael is a thirtysomething bachelor who works at an insurance company. Timid as a mouse, his humdrum routine is broken only by a few minor pleasures, like a skiing weekend with two nerdy pals. Our balding, drably dressed Austrian schlemiel differs from your average Joe only by two tiny details: He has kidnapped a 10-year-old named Wolfgang, whom he keeps locked up in the cellar of his house in the suburbs, and makes him serve regularly as his sexual partner.

What blew my mind about this film wasn't so much the revelation of a crime against a child as it was the context of everyday normality that surrounded it. If you're looking for that doubtful, very American pleasure of seeing the bad guy committing his horrendous deeds and then getting deliciously punished, too bad.

To understand why Schleinzer made his "monster" so normal in other respects, I fielded him a few questions.

BRUCE BENDERSON: The depiction of Michael as an ordinary man increases our identification with him, so that we question our own assumptions and those hidden behind the banalities of everyday life.

MARKUS SCHLEINZER: Definitely. When a crime is committed, the immediate reaction of the neighborhood is typically disbelief: "No one could have guessed"; "He was always so nice and helpful, even fed my cats when I was on vacation." A week after the initial shock comes the desire to distance oneself from the crime. You hear things like, "He was a little odd." A month later, all of them have come to the conclusion that they knew from the start there was a monster among them. This explanation draws a line between their own world and that of evil, so that evil only seems to exist to accentuate the existence of good (whatever that is). However, many of the most horrifying crimes are carried out by seemingly normal people who function well in all areas of life. Given that, I thought it was important to show Michael in a normal context and not as a monster.

BB: The character Michael is banal and ineffectual, isolated and "nerdy." How did such a characterization form in your mind? Why couldn't Michael have been a handsome, dynamic, amusing fellow who acted out the same desires?

MS: That was about hiding and being invisible. Nothing is able to fade out crime better than so-called normality and routine. If you want to stay invisible, follow the rules of society. And yes, it's also about sexual orientation, and not being very happy about it from the start. Michael must have found out about himself very early, and yet wanted to be "normal" and sane in a societal context, so he learned to imitate other people. Handsome, dynamic, and amusing perpetrators are mostly "artists." Then it's about excess, being God. Michael is no artist. He's driven by the same things most of us are. He wants to find happiness in a relationship.

BB: Michael Fuith's performance as Michael is a near miracle. How did you direct him to identify with the character? There had to have been elements in the character that repulsed him.

MS: I gave Michael Fuith quite a hard time, because I had to deal with all his resistance and take away any kind of commentary from him about the character. We started to work on this character a year before shooting. I needed that time because I was sure it would get tough for him again the moment the child actor came to work in the film. We finally succeeded when Fuith decided to play this part not as one person but as many different figures: the office worker, the parent, the boyish bachelor, etc. Fuith's an honest guy with a purity of soul I adore and respect, so he couldn't do otherwise. It would have killed him. And, in fact, there were days when he smashed up the studio.

BB: What are your plans for your next film?

MS: I'm working on a novel [adaptation] by Stefan Zweig. It's about a disabled young woman who claims the possibility of finding and making love. My working title for another script is Porn. Whatever I do, I don't see myself as a teller of fairy tales, like the kind of bedtime stories that have been told for centuries. Follow the "yellow-brick road"? Never.