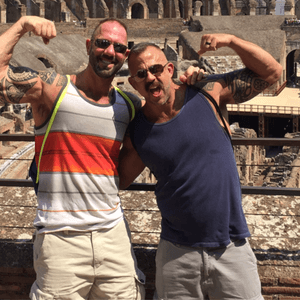

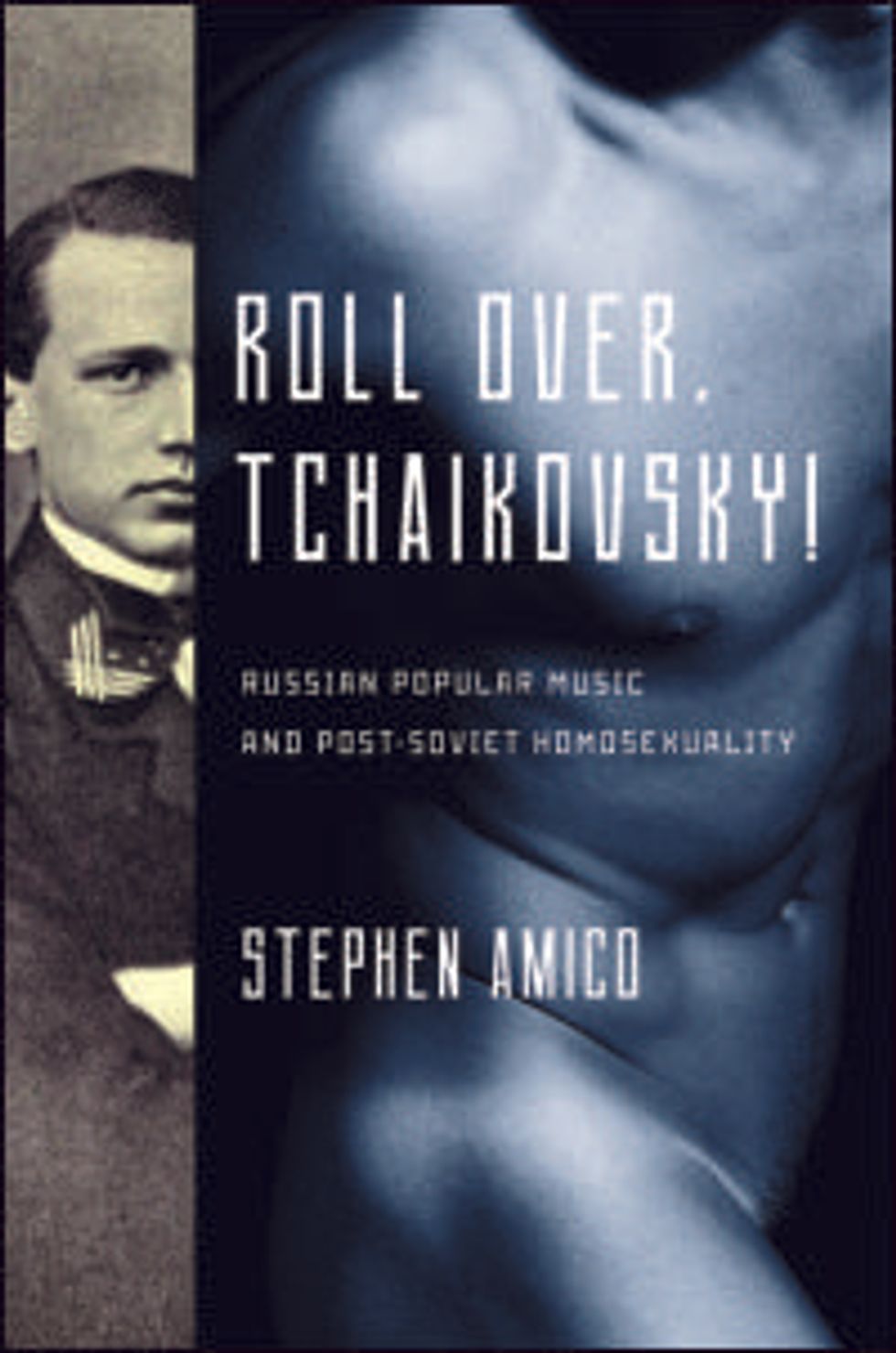

In his groundbreaking study, Roll Over, Tchaikovsky! Russian Popular Music and Post-Soviet Homosexuality, American musicologist Stephen R. Amico analyzes the history Russian rock, pop, and estrada music and how homosexual men's uses of music. Kevin Clarke spoke about how gay men and women are villified in the country, why Tchaikovsky's name has been dragged through the mud, and why Russians love the villainous gay character as portrayed in a St. Petersburg production of Dance of the Vampires.

In Post-Soviet Russia, homophobia is a phenomenon registered with much bewilderment by LGBT people in the West. Why are religious groups and their anti-gay ideologies so powerful in a country that was officially "atheist" for so many decades?

Religious belief or practice in contemporary Russia is never only about "numinous" aspects, but also encompasses those more functional or symbolic. Many have suggested that the demise of the Soviet state left an immense vacuum, and it was the Orthodox Church -- often working hand in hand with the political apparatus -- that filled the void. Additionally, to align one's self with Orthodoxy is, for some, a way of aligning one's self with the Russia of the past, and reviving -- at the level of memory and/or fantasy -- the mighty, pre-revolutionary imperial Russian state. It is also, for others, a ways of defining one's self in contradistinction to the largely Catholic or Protestant west, a way of highlighting one's difference, and one's pride in not being "Western."

Why did the Communists -- who claimed that all men and women are "equal" -- have such a problem with homosexuality too?

In terms of matters related to gender and sexuality, there is a stunning difference between the ideals and agendas one finds in Russia immediately following the revolution, and those that came into being under the leadership of Stalin -- especially as they solidified around the time of World War II. After the revolution, Russia was far more socially progressive than many of its European neighbors, and certainly more so than the United States. Political and social reformers questioned the very necessity of the traditional "nuclear family," many finding it a vestige of bourgeois oppression (especially for women), and suggesting alternative formations that might engender true parity in (gendered) social relations. Indeed, at this time the entire criminal code was re-written, resulting not only in far more liberal legislation regarding divorce and abortion, but also the de-criminalization of homosexuality, something that was still largely illegal in the west. When Stalin came to power, however, the emphasis shifted drastically; "the woman question" was no longer a matter of importance, as it was claimed to have been "solved" by 1929. During this period, the focus was on the consolidation of power, the construction of well-armed, powerful nation, and the regulation and normalization of the populace; in 1933 homosexuality was recriminalized, and by 1934 it seems that the great social experiment had been traded for the Great Terror. Not incidentally, it is during World War II that the antipathy towards homosexuality intensified, due in part to Gorky's conflation of homosexuality with fascism.

Homosexuals were demonized because of their assumed lack of desire to procreate, and thus keep supplying the nation with the raw material of labor -- and cannon fodder. In the context of Russia's current demographic crisis -- both the birth rate and the life expectancy (for men) are among the lowest in the industrialized world -- this is still something that enters the equation.

Is homosexuality still "reeking of bourgeois hedonism" in post-Soviet Russia?

Both historically and currently, there has been the conviction among many Russians that homosexuality is somehow a type of "foreign vice" that is western in origin; so, rather than "bourgeois hedonism," it's likely that many people see this type of "non-traditional sexual orientation" (a common Russian euphemism) as another manifestation of an encroachment of Western capitalist consumer culture and liberal social ideology that threatens to destroy "traditional Russian values." This anti-Western sentiment has, in many ways, grown over the past several years, spurred by such events as the world financial crisis (which many people there blame largely on the United States) and, of course, the current situation in Ukraine.

Although many gay Russian men have strong connections to western popular music and popular culture, and several have told me that they do in some way feel that they are part of a "global gay culture," they are also often highly critical of the west, including what they view as an unnecessary politicization of sexual identity, something they believe should be a private matter -- and many of them do not simply want to take on the identity of the "global gay," which they see as assenting to the cultural hegemony of the U.S. or the U.K. Numerous gay Russian men with whom I spoke did not support any sort of gay pride parade in Moscow or St. Petersburg.

You examine post-Soviet popular music in your book, and remark that even though homophobia is wide-spread there is a "relatively large number of popular music performers whose sexual orientation has been questioned, both by those in the general public and the yellow press." How is it possible?

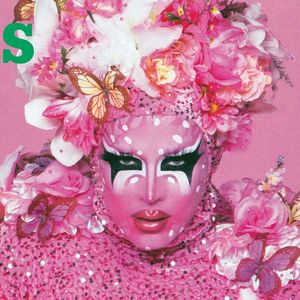

Some suggest that it's simply another instance of a type of theatricality that Russian audiences love, that it is a continuation of a history of Russian dandyism, or that "colorful displays" such as drag performances are used as vehicles for satire, not as an indication of the performers' sexual orientations. And while I imagine that all such dynamics are at least partially responsible for the phenomenon, I also want to avoid erasing the prospect that such musical representations are indeed indicative of a specifically "non-traditional" sexual orientation.

Can you give an example of a "gay" performer?

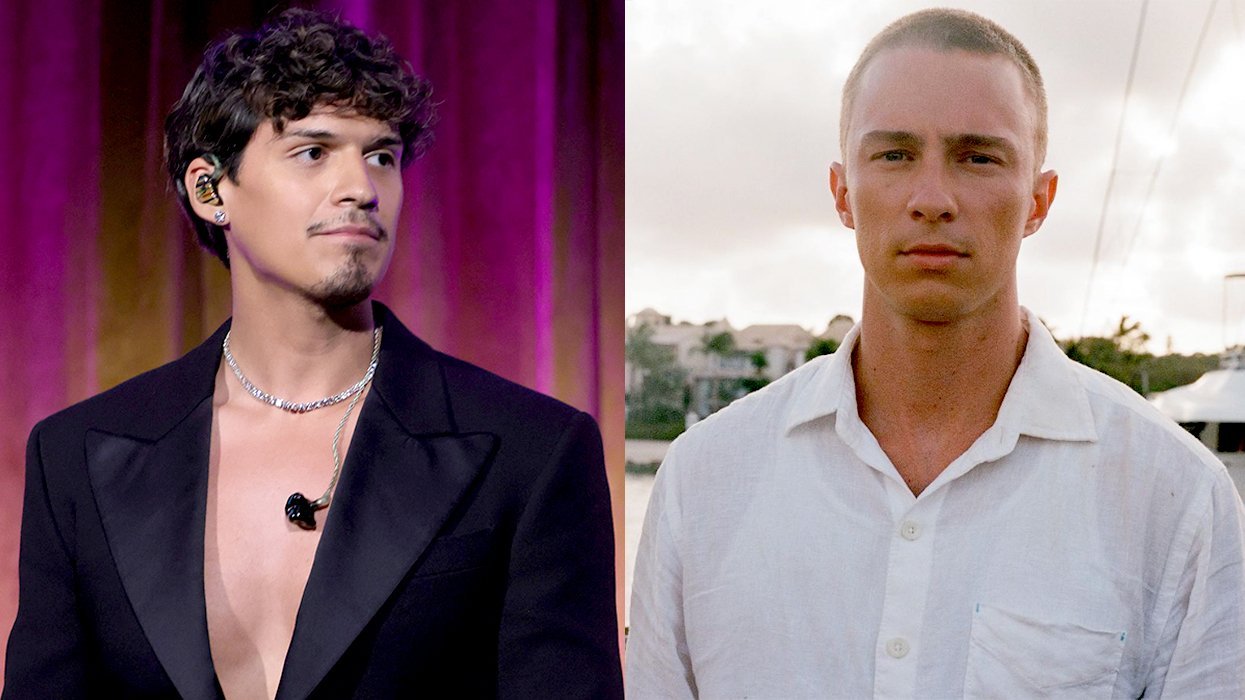

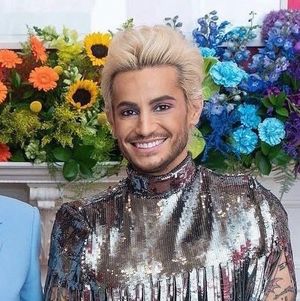

Perhaps Boris Moiseev's "Golubaia luna" ("Blue moon") is the song that is considered by many to be the first "gay" song in contemporary Russian popsa; the lyrics relate a tale of two brothers, one of whom has abjured the love of women for the loneliness of the skies, and the very word "goluboi" - literally, light blue - is common slang for gay. If we are talking about male, Russian performers who roil boundaries of stereotypical gender attributes in various different ways, and whose work features arguably homoerotic themes and images, then the rest of the list is extremely long: Valerii Leont'ev, Dima Bilan, Mitia Fomin (formerly of the group Hi-Fi), Andrei Danilko (and his drag persona Verka Serdiuchka), Sergei Lazarev.

Is it a clever device of Russian activists to use popular music to carve out a living space for gays within the entertainment industry?

Is it a clever device of Russian activists to use popular music to carve out a living space for gays within the entertainment industry?

I'm reluctant to think of it in these terms, as it almost seems to confirm the suspicions (or paranoia) of the government that has led to this legislation against "gay propaganda," and those of right-wing, nationalist figures who suggest that the entertainment industry is ruled by a "gay mafia." I think it might be more accurate to say that there are certainly LGBT people working in the many different types of creative industries in Russia - arenas that are often marked by a higher level of openness and liberalism.

In a recent interview, a stage director of the musical Dance of the Vampire in St. Petersburg claimed that Russian audiences especially love the grotesque gay character in that musical (Herbert, Count von Krolock blond son). How can there be such a gay character in such a "family show," when "gay propaganda" is forbidden?

I haven't seen the St. Petersburg production, and know of the German and US productions only in passing -- but from what I understand, and from the clips I've seen, Herbert is generally portrayed as a stereotypically effeminate, mincing homosexual -- sometimes indeed grotesque -- and one who, not incidentally, is not able to consummate his sexual desires with the male object of his affection, Alfred. So portraying gay men in such unflattering and one-dimensional terms, within narratives where homosexual activity is proscribed and even mocked (the "comical" scene where Herbert tries to seduce Alfred), where heterosexual desire -- that is, Alfred's desire for Sarah -- is the main animating force, and in fantastic/unreal sites - in a fictional tale, on the theatrical stage - fulfills a couple of didactic functions. First, it serves as a way of showing the dangers and limitations of same-sex desire, one that will never be satisfied; and second, it yet again presents the general populace with a caricature of homosexual men, one that not only makes them "identifiable" (and thus avoidable), but also makes them irrevocably "Other" ("they" are not like "us"). I'm relatively certain that theatrical portrayals of same-sex physical and/or emotional desires that are not so pathologized - that represent homosexual men or women as commonplace or ordinary -- would be far less palatable to a general Russian audience; in fact, this is exactly what the legislation against "gay propaganda" seeks to prohibit -- any representation of homosexuality that positions it as "morally" equivalent to heterosexual relationships. In this regard, it seems that Herbert functions more as a cautionary tale, and an object of ridicule, than one of emulation.

Just out of curiosity: Your book deals with popular music, what does Tchaikovsky have to do with that?

The title is obviously a play on the Chuck Berry song, and the suggestion in the lyrics that it's time to roll out the old and bring in the new is part of what I wanted to evoke -- not, of course that we need to banish Tchaikovsky's music, but rather the ridiculous and ultimately homophobic caricatures that have been constructed around his name. It's actually shocking to me that despite rather compelling arguments and evidence to the contrary, the myth of his suicide, supposedly necessitated by a homosexual tryst with the wrong young man, still lives on, not only in the popular consciousness, but in some academic circles as well - and this myth is part and parcel of the construction of the figure of the tragic homosexual, one who risks nothing less than death if he succumbs to corporeal pleasure. In the book, one of my main aims is to highlight the physicality and affective force of music and sexuality -- rather than the simply the cognitive or ideological aspects -- and to argue that attention to the embodied aspects of both is essential. A focus on the living, breathing, sweating, dancing, singing subject can reveal new ways of thinking about sexual identity (theorized through the musical), and is also essential in contemporary Russia in order to at least begin positing the homosexual body as one not moribund, castrated, and pathological, but animated with breath and desire, and coursing with agency. So what we need to do is roll this old "Tchaikovsky" over (and out), and allow for the historical and cultural reading of Tchaikovsky and other LGBT persons in music -- whether in popular culture or in the western canon - that conflates the homosexual with the degenerate in the service of compulsory heterosexuality.

Is it a clever device of Russian activists to use popular music to carve out a living space for gays within the entertainment industry?

Is it a clever device of Russian activists to use popular music to carve out a living space for gays within the entertainment industry?