For 25 years, OUT has celebrated queer culture. To mark our silver jubilee, we look back at some of the biggest, brightest moments of the past 9,131 days.

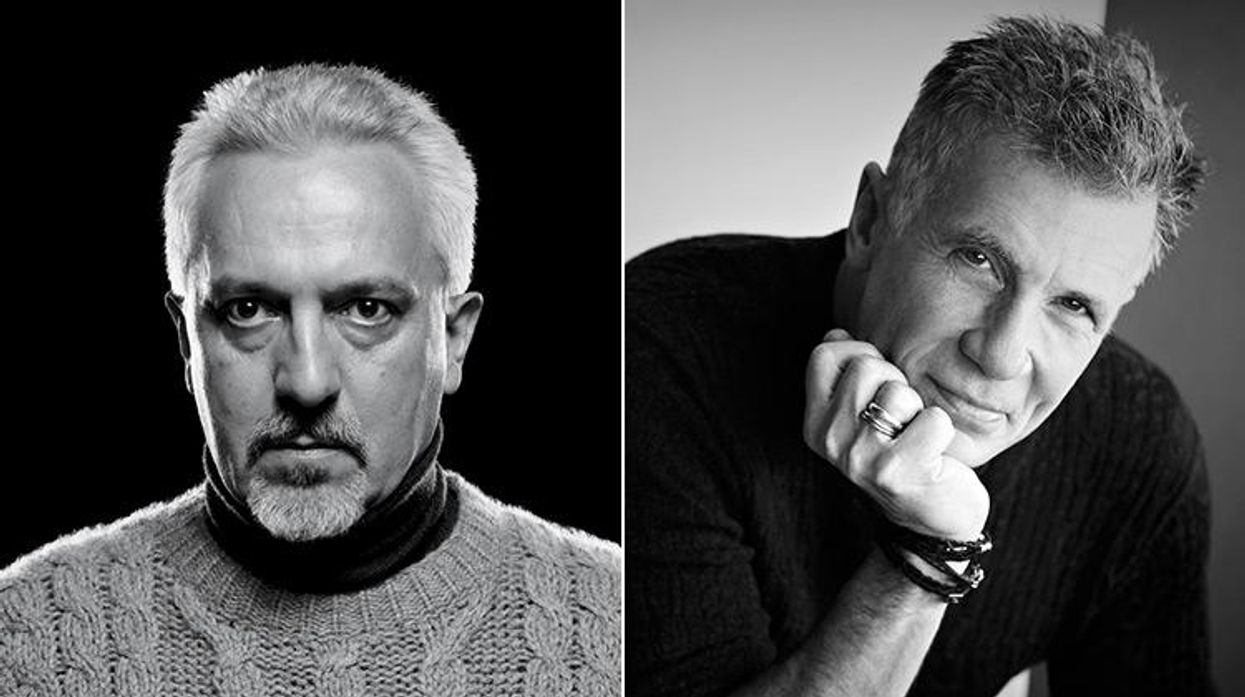

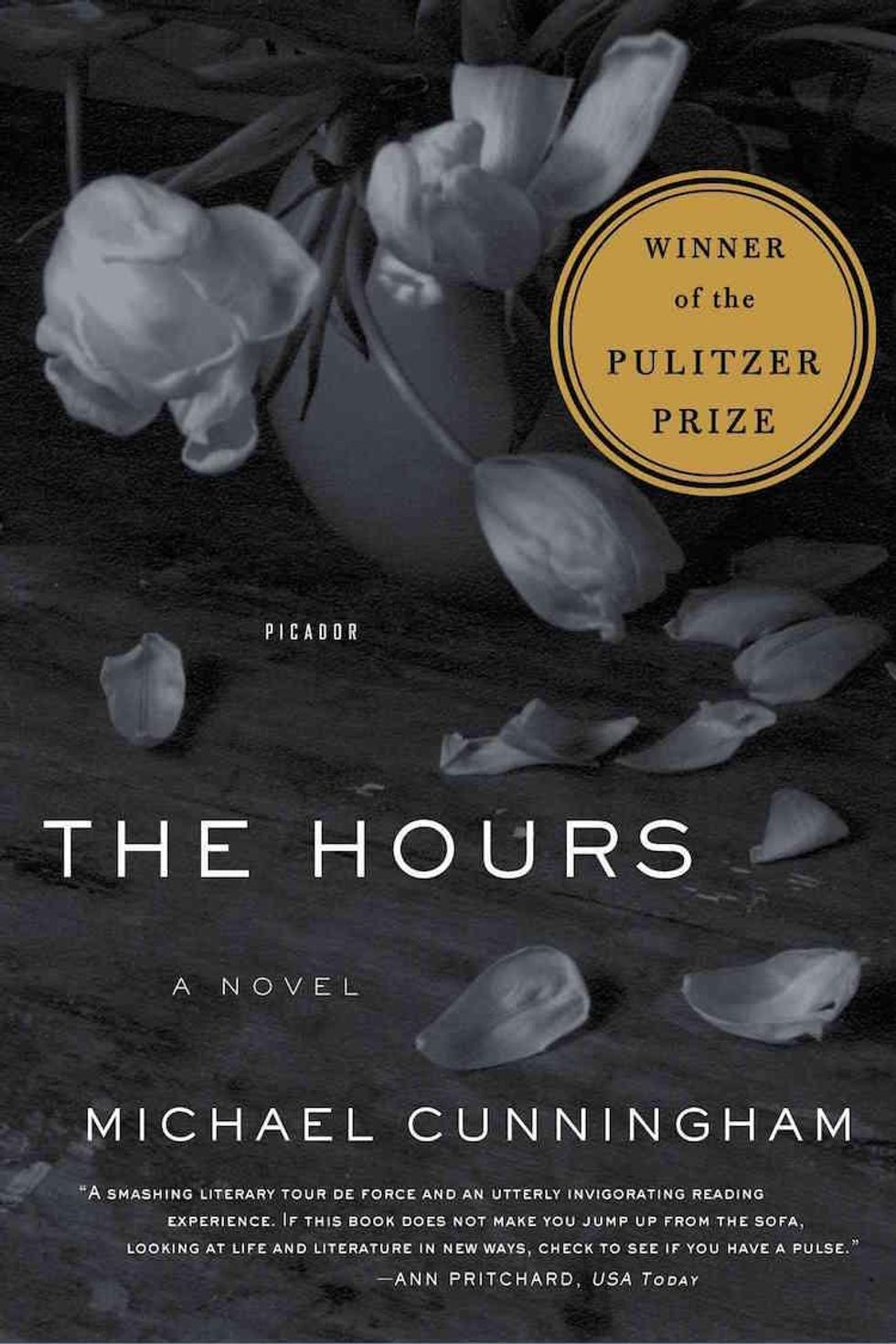

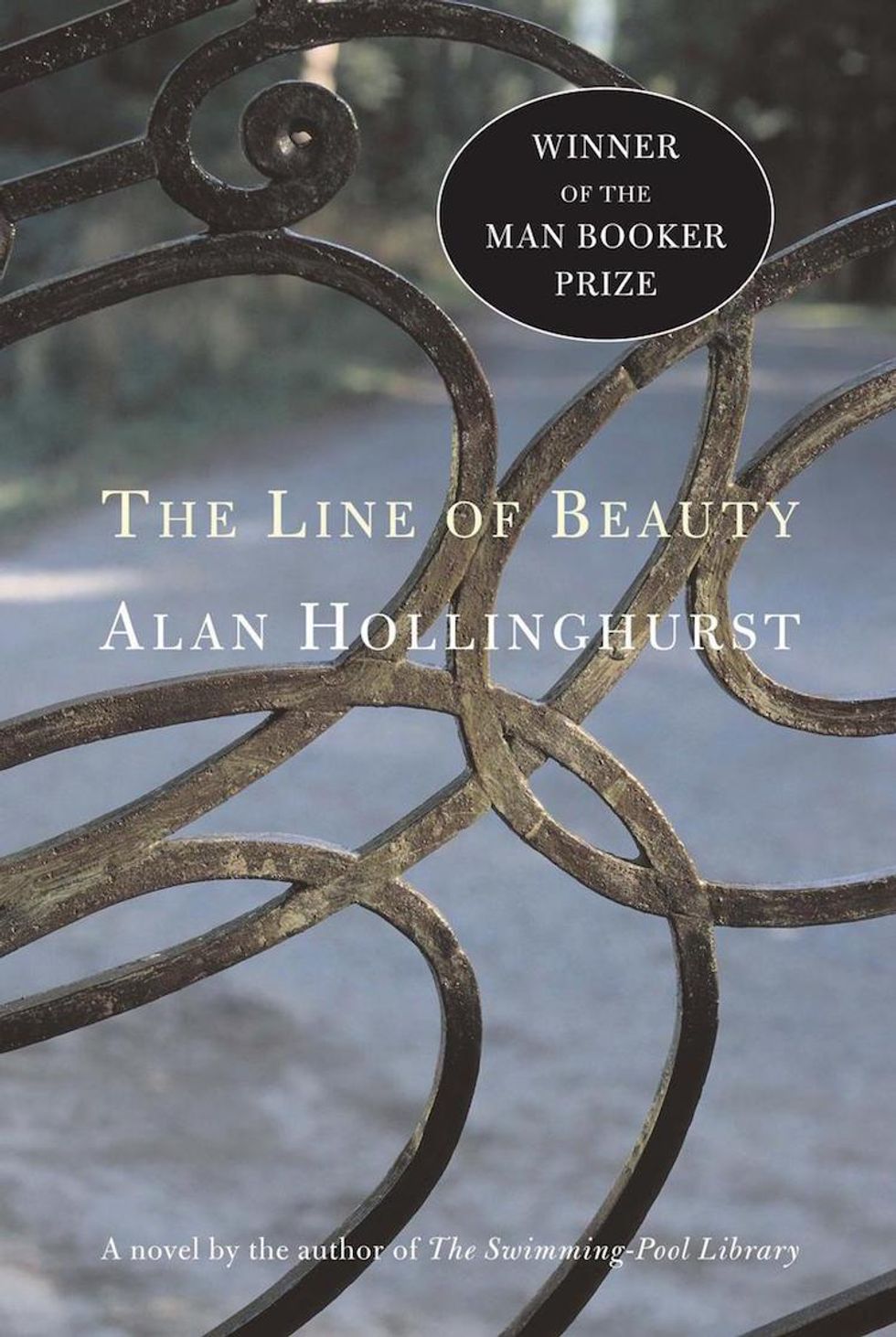

Long thought to be in decline in the 1990s, the queer novel, it turned out, was just gestating into a new phase. Michael Cunningham's 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning The Hours and Alan Hollinghurst's 2004 Man Booker Prize winner, The Line of Beauty, were distinctly gay novels, and both vividly articulated the horrors of AIDS, but they also took a panoramic view of the world, making them more accessible to straight readers. (More recently, the Jamaican writer Marlon James became the first black queer writer to win the Man Booker, with his novel A Brief History of Seven Killings.) It's no coincidence that both Cunningham and Hollinghurst took inspiration from their literary heroes--Virginia Woolf and Henry James, respectively--in creating deceptively classical novels with historical sweep and social nuance. The Hours was a magnificent exercise in literary illusion--and allusion: a series of parallel universes in which the events of Woolf's celebrated novel Mrs Dalloway, set in 1920s London, haunt the characters of 1990s New York and late-1940s California. Hollinghurst took the locus of a classic English novel--a privileged London family mired in compromise and hypocrisy--and added a gay outsider, Nick Guest, who is simultaneously compelled and repelled by what he sees. Here, the two writers look back on the genesis of their novels, and the meaning of their success.

Michael Cunningham: "The Hours was originally going to be a contemporary version of Mrs Dalloway, set among gay men in Chelsea. I'd always loved Mrs Dalloway, and when I moved to Chelsea, in New York, I was struck by the ways in which the London society in which Mrs. D. moved resembled gay Chelsea, or at least the Chelsea of some 20 years ago. When I was writing The Hours, AIDS was still most rampant among gay men, and although the epidemic is far from over, it was so much a part of my life at the time that omitting it from a novel would have been a little like writing about London during World War II without mentioning the Blitz. Mrs Dalloway is set at the end of World War I; it involves a shell-shocked soldier named Septimus Warren Smith. It was natural enough for The Hours' version of Smith to be a poet afflicted with AIDS-related dementia. I'm still, honestly, a little surprised by its reception. It's not necessarily my favorite of my own books. I'd assumed, along with my agent and editor, that it'd sell a few hundred copies and then march with whatever dignity it could muster to the remainders table. I'd be lying if I said [the Pulitzer] meant nothing to me personally, but I'd be lying as well if I said it made me feel all that different. If you look at the list of what many consider the great American novels--from The Sound and the Fury to The Great Gatsby--hardly any of them won a Pulitzer. Frankly, it's made a surprising difference, professionally. Everybody loves a prizewinner. And, OK, it was the first gay novel to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, which mattered to me. Another gay novel would have won the Pulitzer sooner or later, but I'm glad to have been in the right place at the right time, as it were."

Alan Hollinghurst: "The queer novel was novel when I started writing, with urgent and exciting social and political needs and opportunities: expressing a liberated spirit, uncovering a complex past, responding to the crisis of AIDS, among many other things. My first book, The Swimming-Pool Library, had ended in August 1983, on the verge of the great upheavals of the AIDS crisis and the Thatcher boom years--two topics I hadn't treated in my subsequent novels--and I had a sense of unfinished business. So I went back to that moment in 1983 and took the larger story forward. As to the political subject, I knew it had to be treated ironically, exposing the whole ethos of the era through the experience of someone seduced by it--and of course having personal preoccupations of his own. I think the thing of coming to London to lose myself and find myself--common to so many gay people--is clearly mirrored in Nick's journey from the provinces, though he is inadvertently drawn into the center of power in a way I certainly wasn't. Winning the Booker was a lovely thing to happen, and it meant a lot more people read me, and no doubt some of them would never have read about gay sex before. Soon I had enough spare cash to add another floor to my flat, so I live and work in the practical consequences of the prize every day."