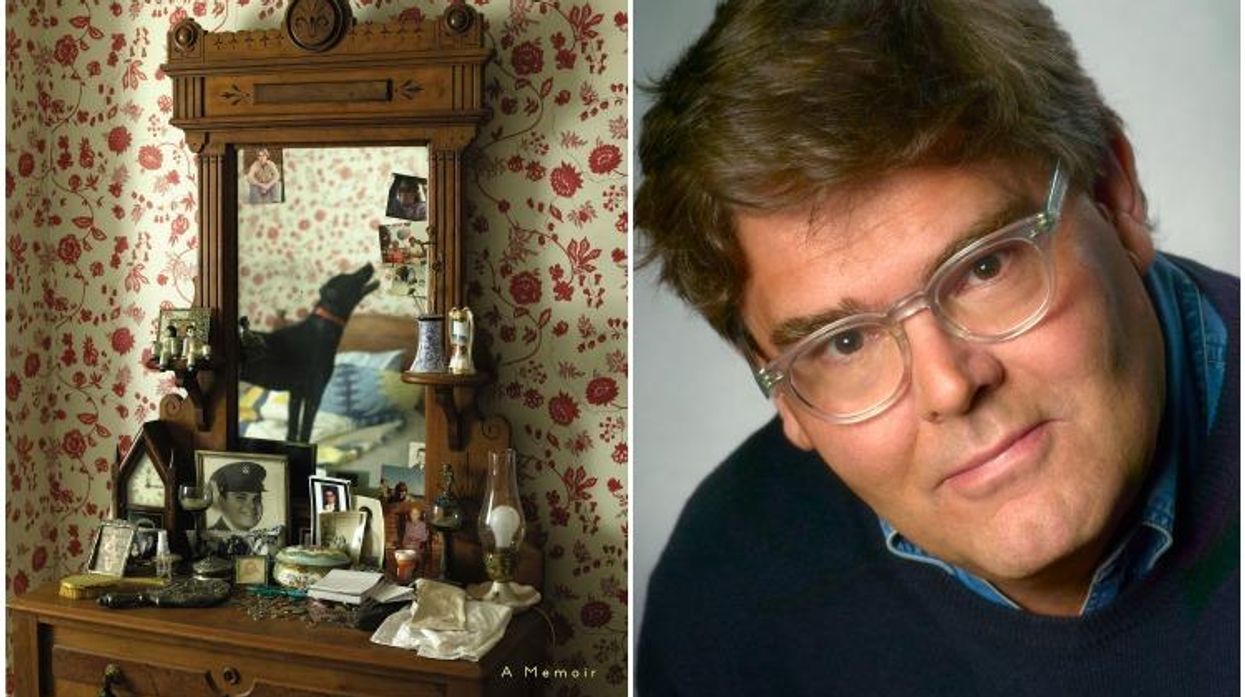

Photo of George Hodgman by Sigrid Estrada

In 2011, my former colleague George Hodgman moved back to Paris, Missouri, to care for his elderly mother, whose physical impairments and descent into the early stages of dementia were gradually encroaching on her ability to care for herself.

At the time, I couldn't believe what he was giving up: He was a successful magazine and book editor with famous friends and a degree of fame himself in certain circles. How could he go from all that to small town America, with its businesses closing up and its young people moving away? How could he spend practically 24-hours a day keeping his mother from hurting herself when, in New York, he seemed unable even to care for a houseplant?

Then, a couple of years ago, Hodgman announced that he was writing a memoir about himself and his mother, Betty. The book, Bettyville has been released to lots of industry buzz. Poignant, hilarious, and skillfully written, it's exactly what you look for in a memoir. I called Hodgman up to talk about dementia, The Golden Girls, and what gay people can get by showing up for their parents.

Do you think that it was a little bit crazy to do what you did four years ago, when you moved back in with your 90-year-old mother in Missouri?

I've sort of come to terms with the fact that most of my decisions will, sooner or later be considered "a little bit crazy" by myself and/or others. But I didn't decide to move back in exactly those terms. I had been spending a lot of time in Missouri anyway, and I came home for her birthday and--though she waited some time to reveal this--she had lost her driver's license. At that point, she was only driving to the store and church, but it meant she was going to be completely stranded in her house and that just isn't my mother. My mother is an archetypal American spirit. She's gotta move, travel, ramble. She's never been the kind to stay home and stare at the soaps.

It was kind of a question of stay or watch her get depressed and fade away. Or some kind of assisted-living situation. Unsurprisingly, the latter option didn't thrill her. Or me. So I decided to stay for a while and it just got longer and this happened and that happened. More problems, you know. Fewer friends. After 90, even Madonna doesn't call. I didn't want her to be lonely and... I was just available. I also realized, as time passed, that I had been really lonesome, too, and that there was something comforting about being here. I had lost my job and was freelancing. My apartment building was so empty during the day. I felt like, you know, Sigourney in Aliens, stuck on the ghost ship. And I have a tendency to get in trouble when I'm not in a real structured situation. It just all evolved. It was just for another day, another week or month. Suddenly it was a year and I realized that I didn't miss New York as much as I thought I would.

In the book, Betty seems quite lucid (and devastatingly funny) one minute, then confused and scared the next. How frequent are the "good days" and "bad days"?

Well, that was the summer of 2012. She was starting then to become very obsessive and ritualistic about trying to remember words and other things, but the nights were already starting to get harder and harder. She's never lost her personality or her ability to be occasionally wry, but there's this sense of anxiety she carries because she knows something is happening to her. She goes through periods where it seems like she's getting worse and then she has these periods where she seems to have hit a plateau and is kind of coasting at that level. She's kind of all over the map and her physical health is also an issue. The mind and the body, you know--very connected.

Dementia causes some physical problems and those problems exacerbate the dementia and it's complicated. She is very strong and very vulnerable, sweet and strong-willed (very) and, yes, funny. She gets obsessed with things. Recently she has been reading and re-reading The Secret Confessions of Ava Gardner. She tells everyone, "It's the filthiest thing I've ever read. You ought to read it." When Ava goes to bed with someone, such as Frank Sinatra (who I believe you also dated), she refers to it as being "in the feathers." This engaged my mother's imagination. If I come out with my hair in its usual bird's-nest style, she says, "You look like you've been in the feathers." I say, "I wish."

The bad times, well -- they happen more and more often. Sometimes I just lie in bed in the afternoons because I can't deal with her asking the same questions over and over. I stay up really late at night just to have some quiet time to myself. My hours are very unorthodox.

Betty is so cranky, and you're so snarky, at times I pictured the two of you as Statler and Waldorf while I was reading your book. You talk in the book about how dissimilar the two of you are, but do you think you got your sense of humor from your mother?

You know, the woman who helps us, Carol, kept saying how funny we are. We have always had this bantering, bickering, jokey way of speaking to each other. Sometimes it shocks people. But I think I decided to do the book because of the humor and the slightly Harold and Maude eccentricity. I think I did get her humor and her family's humor, but a lot of Missourians in this area are very dry. You know that Twain guy, Mark Twain. He was from down the road. Missourians are funny except when they decide to talk about how much they love their guns, which they tend to do. Occasionally, there is the random comment about shooting the President. Like me, Betty is a Democrat. When people start bugging her with talk about Obama, she yells across the table, "Be still!" This tends to throw a determined Republican matron who has just arrived with a perfectly respectable Jell-O salad into a state of, well, concern. Anyway, this is a long way of saying that I didn't want the book to go in either a too tragic or too Hallmark direction. I started listening for the times when we were kind of our own kind of comedy team.

Do you two talk about what it is that you're doing for her? Has she expressed any gratitude to you?

Older people are not great with gratitude. Also, my mother is sort of in denial about what I'm doing. If she allows herself to be too conscious of the fact that I am here, leading this sort of Emily Dickinson lifestyle, she will become too guilty and sad.

I think she has to kind of tuck the reality of how this has changed my life away. My mother has always been fierce in her attempts to make me independent. When I was a toddler, she sent me on a cruise. I mean she was always trying to get me out of the house when I only wanted to turn her closet into a Saks branch. She would never tolerate this if she weren't really scared. It doesn't bother me that she isn't gushing out thanks. But I do wish, since I have worked hard to learn to sort of cook, that she would say she liked a meal. I say, "How was that?" She always just says, "fine." Sometimes you want to just scream, "If you were in a nursing home, you'd have a scoop of tuna salad, old woman." But you don't, because five minutes later she does something that nearly makes you cry.

Speaking of Saks branches, I get the sense that you've never discussed your being gay with your mother. Is that because you fear that she wouldn't approve?

We talked about it. It wasn't the greatest interaction we ever had. Then we talked about it a little more. Every time I brought it up, she seemed surprised that I hadn't changed. I think she thought gay was sort of like having a cold or maybe being pregnant. It was kind of temporary. Gay is just not part of her experience here.

She never knew gay people and it's not like she is just determined to bring up anything that involves sex. At least not until she started reading Ava Gardner. Now it's "the feathers" all the time. Anyway, we have evolved a way of loving and supporting each other that doesn't involve conversations about things that are uncomfortable for her. I should have tried harder to bring her along. I would discuss this more, in more depth, but you would need a ten thousand-word article. We are not a case study in parent-child communication, but the fact that we are the way we are makes for a better book, a more interesting situation.

Well, as the country ages, as we gray, I think more and more of us are going to have to start doing what you're doing. I wonder if it's going to be harder for the gays, since our relationships with our parents are often problematic.

Well, it feels like dementia and Alzheimer's are almost epidemic, but look at America. Everybody's nuts. At least the elderly have some sort of chemical reason. I think that it is appropriate for children to be drawn into caring in some way for their elders. They cared for us. It's natural. It's a part of life that you have to deal with and it doesn't feel like some terrible obligation because you love them. You may never love them so much as when you see them trying so hard to hang on.

Also, the thing is--even though it is stressful and often exhausting--it does make you more human. I didn't have kids. I didn't have pets. I couldn't keep a cactus alive. This has been good for me. Hard. But I'm less self-centered. Which leaves me still very self-centered. Betty and I are kind of the country and western Debbie Reynolds and Carrie Fisher. We do have some fun.

I imagine my own old age as sort of like The Golden Girls, where me and some friends rent a house and savage each other verbally until we die. I'd be Dorothy and you, of course, would be Rose. So what about you--do you ever think about your own old age, and who might take care of you?

I think about my old age a lot. I think The Golden Girls got it right. You need a family, a community, I think. I'd love to have a nice old house with great old friends, if we all hard a place to be private, too. I don't want to be alone.

Oh! And [our mutual friend] Johnathan would be Blanche!

Johnathan would monopolize the bathroom. He grooms, what, nine hours a day?

I remember reading a very early excerpt from Bettyville, and then, a couple of years later, when your agent was shopping it around, I heard about it from, like, every editor at every publisher. It seemed like everyone wanted to publish your book. How did that make you feel?

There weren't that many who wanted to publish it. I mean, people said it was "small." Publishers still think gay doesn't sell. Dementia victims aren't exactly the new Fifty Shades of Grey. I got the usual amount of rejections, but I expected that. I was happy with the people who liked it the most. They were the people who I kind of most wanted to please, people whose books I liked, people who I thought were not just good editors but nice human beings. Overall, the process of selling a book is pretty confusing. There is such a range of opinion and you kind of have to just tell the agent, "Call me when someone brings up money," because it is hard to know whether you have written something good or something that is completely unpublishable. Also, memoir is really hard because it's you, bare and vulnerable. When they say the main character is not likable, well, you tend to notice it a bit.

But now it's out and getting amazing notices. One last question: do you worry at all about what Betty will think of Bettyville?

Yes. Handling Betty's feelings about the book that came out of this is very difficult. I want to make her part of the process if it's a good process. You know, let her be happy if it's successful. But there is so much in this book that would make her uncomfortable. I think I am going to just say, "Here, here's my book, and give her Gone With the Wind."

Bettyville is available now.